For Russians Deprived of Meaningful Political Choice Doing Nothing Is Still Not an Option

Interpreting the September 2024 Russian elections

By Olga Gushchina October 10, 2024

Interpreting the September 2024 Russian elections

By Olga Gushchina October 10, 2024

Twice a year, in September and March, Russia holds “unified voting days” when all regular local and regional elections are scheduled. Every six months we observe the ways in which the creeping changes to the electoral legislation manifest in new mechanisms for securing the results required to uphold the perception of legitimacy.

Despite administrative and political pressure, activists in Russia continue to attempt political participation as candidates and observers. This is an important and sometimes desperate way to show that they are not giving up.

On September 8, 2024, more than 4,000 electoral campaigns at various levels across over 80 regions of Russia concluded.

They included by‑elections for State Duma deputies in three districts, governor elections in 21 regions, elections for deputies to 13 regional parliaments and 20 city councils, elections for two mayors of regional capitals and for numerous municipal councils, including 111 St. Petersburg municipalities.

Twice a year, in September and March, Russia holds “unified voting days” when all regular local and regional elections are scheduled. Every six months we observe the ways in which the creeping changes to the electoral legislation manifest in new mechanisms for securing the results required to uphold the perception of legitimacy.

Despite administrative and political pressure, activists in Russia continue to attempt political participation as candidates and observers. This is an important and sometimes desperate way to show that they are not giving up.

On September 8, 2024, more than 4,000 electoral campaigns at various levels across over 80 regions of Russia concluded.

They included by‑elections for State Duma deputies in three districts, governor elections in 21 regions, elections for deputies to 13 regional parliaments and 20 city councils, elections for two mayors of regional capitals and for numerous municipal councils, including 111 St. Petersburg municipalities.

In 49 regions, the voting lasted three days; there were two days of voting in 13 regions, and the elections only lasted for one day (September 8) in 21 regions. In a number of regions, including the illegally occupied territories of Ukraine, there was also early voting period that lasted from August 28 to September 5, 2024.

The official rationale for early voting was “ensuring the security of citizens”, while multi‑day voting, first introduced in the summer of 2020, during the pandemic, was purpotedly introduced for their convenience. Both give the commissions uncontrolled access to the used ballot papers at night, significantly hindering observation

In 49 regions, the voting lasted three days; there were two days of voting in 13 regions, and the elections only lasted for one day (September 8) in 21 regions. In a number of regions, including the illegally occupied territories of Ukraine, there was also early voting period that lasted from August 28 to September 5, 2024.

The official rationale for early voting was “ensuring the security of citizens”, while multi‑day voting, first introduced in the summer of 2020, during the pandemic, was purpotedly introduced for their convenience. Both give the commissions uncontrolled access to the used ballot papers at night, significantly hindering observation

The process and the results of the vote were not unexpected: we saw the expansion of suppression of citizens' participation in politics, further monopolization of power, and the creation of the illusion that citizens consolidated around the President and the ruling party.

The process and the results of the vote were not unexpected: we saw the expansion of suppression of citizens' participation in politics, further monopolization of power, and the creation of the illusion that citizens consolidated around the President and the ruling party.

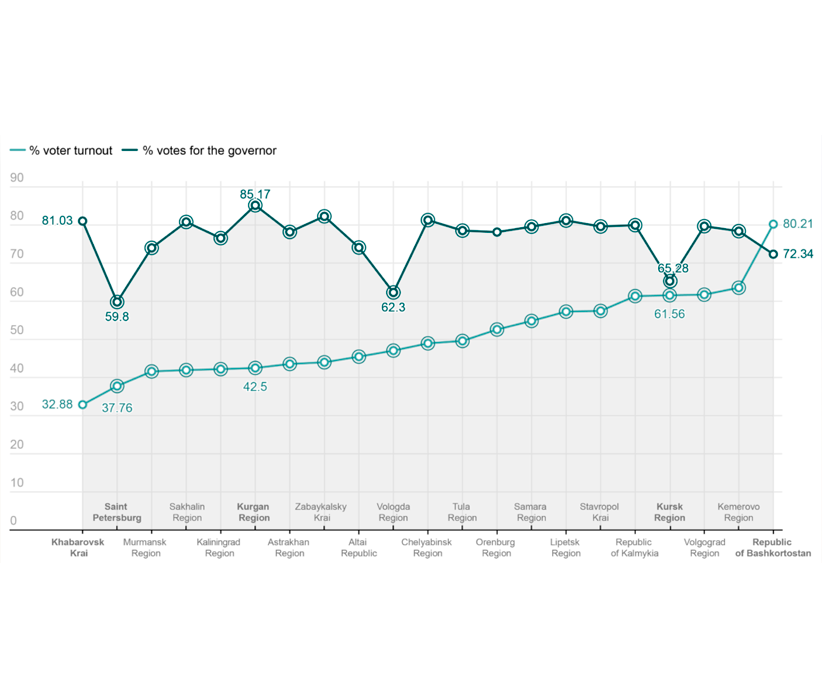

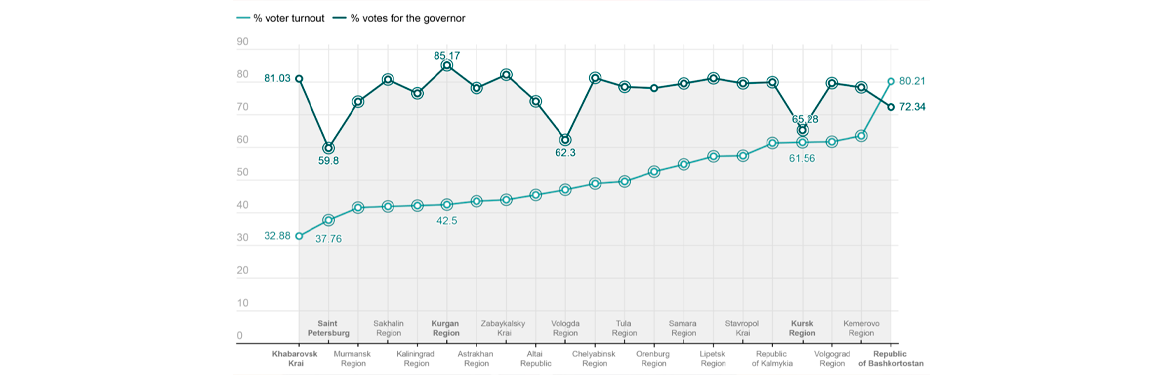

Predictably, the direct elections of the region’s heads resulted in victories of 13 incumbent and 8 acting governors.

Predictably, the direct elections of the region’s heads resulted in victories of 13 incumbent and 8 acting governors.

According to official data, St. Petersburg Governor Beglov had the worst result (59.8% of votes with a turnout of 37.76%), while the lowest turnout (32.88%) took place in Khabarovsk Krai. Kursk Oblast, where some districts are controlled by the Ukrainian army, officially became one of the leaders in terms of turnout (61.56%).

Nevertheless, these elections provide valuable insights into broad processes taking place within the Russian state and society. We will examine the election campaigns and their outcomes along four thematic vectors:

According to official data, St. Petersburg Governor Beglov had the worst result (59.8% of votes with a turnout of 37.76%), while the lowest turnout (32.88%) took place in Khabarovsk Krai. Kursk Oblast, where some districts are controlled by the Ukrainian army, officially became one of the leaders in terms of turnout (61.56%).

Nevertheless, these elections provide valuable insights into broad processes taking place within the Russian state and society. We will examine the election campaigns and their outcomes along four thematic vectors:

According to official Russian data, there are about 1.5 million voters in Crimea. Among them are Ukrainians who were forcibly issued Russian passports after 2014, migrants from the Ukrainian territories occupied after February 2022 who temporarily reside in Crimea, and Russians who moved to the peninsula within the past ten years. There are 1,317 polling stations on the peninsula, including those in hospitals and detention centers.

According to official Russian data, there are about 1.5 million voters in Crimea. Among them are Ukrainians who were forcibly issued Russian passports after 2014, migrants from the Ukrainian territories occupied after February 2022 who temporarily reside in Crimea, and Russians who moved to the peninsula within the past ten years. There are 1,317 polling stations on the peninsula, including those in hospitals and detention centers.

It is also possible to vote online through Gosuslugi (the State Services portal) or near one’s home, using the Mobile Voter program. About 150 mobile polling stations operated in locations with difficult access and also without premises suitable for voting or with unreliable transportation.

According to Radio Liberty, four extraterritorial polling stations have been established near the front line for servicemen of the Russian army stationed in Crimea and participating in the aggression against Ukraine. The election in Sevastopol started early on August 28.

According to the Ukrainian National Resistance Center, Russian authorities are inflating turnout numbers with the help of security forces in Crimea. It is impossible to observe the election process at mobile polling stations or online, which calls into question the results of voting that was illegal in the first place.

In other words, Russia has brought to the occupied Ukrainian territories the malign practices of vote manipulation, involving citizens of the occupied region in them.

It is also possible to vote online through Gosuslugi (the State Services portal) or near one’s home, using the Mobile Voter program. About 150 mobile polling stations operated in locations with difficult access and also without premises suitable for voting or with unreliable transportation.

According to Radio Liberty, four extraterritorial polling stations have been established near the front line for servicemen of the Russian army stationed in Crimea and participating in the aggression against Ukraine. The election in Sevastopol started early on August 28.

According to the Ukrainian National Resistance Center, Russian authorities are inflating turnout numbers with the help of security forces in Crimea. It is impossible to observe the election process at mobile polling stations or online, which calls into question the results of voting that was illegal in the first place.

In other words, Russia has brought to the occupied Ukrainian territories the malign practices of vote manipulation, involving citizens of the occupied region in them.

Until 2023, voting in regional‑level elections was possible only within the boundaries of a federal subject. A resident of St. Petersburg or Samara Oblast could not vote for the governor of his or her region while in Moscow or Vladivostok.

On the unified voting day in 2023, the mechanism of extraterritorial polling stations was introduced. At the time, residents of the annexed regions took advantage of the opportunity to vote.

In Donetsk and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts, early voting for residents of hard‑to-reach areas and territories close to the line of contact began on August 31. In Luhansk and Kherson Oblasts, on September 2.

From September 1 to 4, warzone refugees from occupied territories could vote at 328 extraterritorial polling stations established throughout 81 regions of the Russian Federation, Vedomosti reported. At the same time, extraterritorial polling stations were set up in these territories for deployed military personnel who are formally residents of other regions of the Russian Federation.

Until 2023, voting in regional‑level elections was possible only within the boundaries of a federal subject. A resident of St. Petersburg or Samara Oblast could not vote for the governor of his or her region while in Moscow or Vladivostok.

On the unified voting day in 2023, the mechanism of extraterritorial polling stations was introduced. At the time, residents of the annexed regions took advantage of the opportunity to vote.

In Donetsk and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts, early voting for residents of hard‑to-reach areas and territories close to the line of contact began on August 31. In Luhansk and Kherson Oblasts, on September 2.

From September 1 to 4, warzone refugees from occupied territories could vote at 328 extraterritorial polling stations established throughout 81 regions of the Russian Federation, Vedomosti reported. At the same time, extraterritorial polling stations were set up in these territories for deployed military personnel who are formally residents of other regions of the Russian Federation.

In the fall of 2024, the election commissions of Kemerovo, Kurgan, Murmansk, Lipetsk Oblasts, Khabarovsk and Stavropol Krais, the Republic of Tuva, and St. Petersburg announced the establishment of extraterritorial polling stations in the occupied territories.

Interestingly, the St. Petersburg election commission mentions only two polling stations in Mariupol, which are intended for St. Petersburg residents engaged in the reconstruction of the city and police officers serving there.

However, as follows from the publications of the head of the SPbEC, “servicemen in the SMO (Special Military Operation) zone take part in voting in the elections of the Governor of St. Petersburg. Extraterritorial polling stations were opened in military units on the territories of the Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson Oblasts”.

This may mean that in addition to the public resolutions of the election commission there are also classified ones.

In the fall of 2024, the election commissions of Kemerovo, Kurgan, Murmansk, Lipetsk Oblasts, Khabarovsk and Stavropol Krais, the Republic of Tuva, and St. Petersburg announced the establishment of extraterritorial polling stations in the occupied territories.

Interestingly, the St. Petersburg election commission mentions only two polling stations in Mariupol, which are intended for St. Petersburg residents engaged in the reconstruction of the city and police officers serving there.

However, as follows from the publications of the head of the SPbEC, “servicemen in the SMO (Special Military Operation) zone take part in voting in the elections of the Governor of St. Petersburg. Extraterritorial polling stations were opened in military units on the territories of the Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson Oblasts”.

This may mean that in addition to the public resolutions of the election commission there are also classified ones.

Such extraterritorial polling stations are set up through an opaque process behind closed doors, without public oversight. The principles for compiling the lists of voters are unknown; the voters' access to the information about the elections and their free expression of will are limited. In addition, it is a very complicated process: the extraterritorial polling stations are under the purview of the regional territorial election commissions.

Members of election commissions report challenges with the physical delivery of ballots from the occupied territories. There has been a report of unverifiable data transmitted electronically on the election day and combined with the votes of residents who voted in their regions.

Such extraterritorial polling stations are set up through an opaque process behind closed doors, without public oversight. The principles for compiling the lists of voters are unknown; the voters' access to the information about the elections and their free expression of will are limited. In addition, it is a very complicated process: the extraterritorial polling stations are under the purview of the regional territorial election commissions.

Members of election commissions report challenges with the physical delivery of ballots from the occupied territories. There has been a report of unverifiable data transmitted electronically on the election day and combined with the votes of residents who voted in their regions.

Thus, votes from the extraterritorial polling stations distort data on voter turnout and the expression of will, becoming another instrument of manipulation deployed in the illegally occupied territory of Ukraine; the Russian regional election commissions are involved in the organization of voting contrary to international law.

Thus, votes from the extraterritorial polling stations distort data on voter turnout and the expression of will, becoming another instrument of manipulation deployed in the illegally occupied territory of Ukraine; the Russian regional election commissions are involved in the organization of voting contrary to international law.

A fundamentally new situation has developed in Kursk Oblast, where several districts are controlled by the Ukrainian armed forces and a counter‑terrorist operation regime had been proclaimed by the Russian government. Eight districts of Kursk Oblast are in the evacuation and resettlement zone.

The regional election commission has postponed the local elections in 7 out of 33 municipalities but has not postponed the gubernatorial elections. Early voting began on August 28 and lasted 12 days. Remote electronic voting (REV) was also held.

According to the official numbers, despite the active hostilities, the loss of territory, and the forced evacuation of about 15% of the region’s population, turnout in these elections was almost 50% higher than in the 2019 gubernatorial elections (more than 60% vs. 41.56%).

The 100% turnout was registered by extraterritorial polling stations formed in the regions of Russia where residents of border districts of Kursk Oblast had moved.

A fundamentally new situation has developed in Kursk Oblast, where several districts are controlled by the Ukrainian armed forces and a counter‑terrorist operation regime had been proclaimed by the Russian government. Eight districts of Kursk Oblast are in the evacuation and resettlement zone.

The regional election commission has postponed the local elections in 7 out of 33 municipalities but has not postponed the gubernatorial elections. Early voting began on August 28 and lasted 12 days. Remote electronic voting (REV) was also held.

According to the official numbers, despite the active hostilities, the loss of territory, and the forced evacuation of about 15% of the region’s population, turnout in these elections was almost 50% higher than in the 2019 gubernatorial elections (more than 60% vs. 41.56%).

The 100% turnout was registered by extraterritorial polling stations formed in the regions of Russia where residents of border districts of Kursk Oblast had moved.

The mathematical analysis conducted by the Golos movement indicates considerate ballot stuffing in favor of the governor and inflated turnout numbers.

The authorities, however, are trying to save face and show that everything that happens on the frontline mobilizes the population to vote:

The mathematical analysis conducted by the Golos movement indicates considerate ballot stuffing in favor of the governor and inflated turnout numbers.

The authorities, however, are trying to save face and show that everything that happens on the frontline mobilizes the population to vote:

“It’s always like this with us: trouble, danger, people pull together. In this case, people have shown that they will not be intimidated by any blackmail, by any psychological attacks, by shells,“ CEC head Ella Pamfilova asserted during a September 7 briefing.

“It’s always like this with us: trouble, danger, people pull together. In this case, people have shown that they will not be intimidated by any blackmail, by any psychological attacks, by shells,” CEC head Ella Pamfilova asserted during a September 7 briefing.

“Despite the fact that the enemies tried to intimidate those who live in Kursk, to bring chaos into our minds, they have failed, because in the face of the threat we stick together as never before,“ said State Duma deputy Ekaterina Kharchenko.

“Despite the fact that the enemies tried to intimidate those who live in Kursk, to bring chaos into our minds, they have failed, because in the face of the threat we stick together as never before,” said State Duma deputy Ekaterina Kharchenko.

We see that the Russian authorities are willing to show at all costs that the population supports the war regardless of the territorial losses and material damage. The narrative of broad support for the authorities in the border areas is an important tool of domestic propaganda.

We see that the Russian authorities are willing to show at all costs that the population supports the war regardless of the territorial losses and material damage. The narrative of broad support for the authorities in the border areas is an important tool of domestic propaganda.

In his address to the Federal Assembly (it was, in fact, his election speech) on February 29, 2024, President Vladimir Putin said that “participants of the special military operation, toilers and warriors, should be recognized as the elite of Russia, should participate in its governance and major projects.“

One could assume that war veterans would also be invited to participate in local and regional elections. This is exactly what happened.

In regional elections at different levels, United Russia nominated 380 veterans of the war; 308 of them will receive mandates, said the acting secretary of the party’s general council Vladimir Yakushev. These are mostly 30–50‑year-old officers who were involved with military training and service before February 2022.

Let’s take a look at some of the winners.

In Salekhard, Yury Novopoltsev, head of the Yamal branch of the Association of Combat Operations, got elected into the city council; while in Noyabrsk, Igor Pronin, head of the guard of the security unit of a Gazprom branch, won the election. According to Ura.ru, both are veterans of combat operations in Ukraine.

In his address to the Federal Assembly (it was, in fact, his election speech) on February 29, 2024, President Vladimir Putin said that “participants of the special military operation, toilers and warriors, should be recognized as the elite of Russia, should participate in its governance and major projects.”

One could assume that war veterans would also be invited to participate in local and regional elections. This is exactly what happened.

In regional elections at different levels, United Russia nominated 380 veterans of the war; 308 of them will receive mandates, said the acting secretary of the party’s general council Vladimir Yakushev. These are mostly 30–50‑year-old officers who were involved with military training and service before February 2022.

Let’s take a look at some of the winners.

In Salekhard, Yury Novopoltsev, head of the Yamal branch of the Association of Combat Operations, got elected into the city council; while in Noyabrsk, Igor Pronin, head of the guard of the security unit of a Gazprom branch, won the election. According to Ura.ru, both are veterans of combat operations in Ukraine.

As part of the Ryazan Oblast Duma election, Roman Igolkin, a participant of the SMO, has won in constituency No. 12, writes Rzn.info, citing the local election commission. In the Kirov Oblast, Artyom Zabolotskikh, a participant of the military operation, has won the election for the post of the head of Podosinovsky district, reports the Vyatka‑on-the‑Net publication.

In the by‑election to the Nizhny Novgorod City Duma in single‑mandate constituency No. 30, Colonel Evgeny Chintsov, a soldier of the SMO and an alumnus of the Time of Heroes program, was in the lead, reports GTRK Nizhny Novgorod.

As part of the Ryazan Oblast Duma election, Roman Igolkin, a participant of the SMO, has won in constituency No. 12, writes Rzn.info, citing the local election commission. In the Kirov Oblast, Artyom Zabolotskikh, a participant of the military operation, has won the election for the post of the head of Podosinovsky district, reports the Vyatka‑on-the‑Net publication.

In the by‑election to the Nizhny Novgorod City Duma in single‑mandate constituency No. 30, Colonel Evgeny Chintsov, a soldier of the SMO and an alumnus of the Time of Heroes program, was in the lead, reports GTRK Nizhny Novgorod.

The introduction of former military personnel into civilian structures of local government will likely increase the attractiveness of the military service and offer paths for integration into life after leaving the service, plus strengthen local control.

The introduction of former military personnel into civilian structures of local government will likely increase the attractiveness of the military service and offer paths for integration into life after leaving the service, plus strengthen local control.

According to the Deputies of Peaceful Russia Association, there are more than 150 former and current deputies with an anti‑war stance in exile. The number of activists who could have promoted the anti‑war agenda as part of election campaigns had they not left the country and provided organizational and leadership structure is dozens of times greater.

It is not surprising that in the context of military censorship and repression the topic of war did not become the centerpiece of the past elections.

The Yabloko party, which attempted to campaign under the slogan “For Peace and Freedom” with a more demure stipulation- “For a ceasefire agreement” -had nominated 301 candidates, most of whom were not registered or were later withdrawn.

According to the Deputies of Peaceful Russia Association, there are more than 150 former and current deputies with an anti‑war stance in exile. The number of activists who could have promoted the anti‑war agenda as part of election campaigns had they not left the country and provided organizational and leadership structure is dozens of times greater.

It is not surprising that in the context of military censorship and repression the topic of war did not become the centerpiece of the past elections.

The Yabloko party, which attempted to campaign under the slogan “For Peace and Freedom” with a more demure stipulation- “For a ceasefire agreement” -had nominated 301 candidates, most of whom were not registered or were later withdrawn.

9 out of the 59 Yabloko candidates who managed to register have been elected to municipal councils in Pskov (7), Ryazan (1), and Novgorod (1) Oblasts.

The government has responded to Yabloko’s success in Pskov Oblast with political repressions targeting the party’s regional leader Lev Shlosberg: on October 2, his apartment was searched as part of a criminal investigation of a violation of the Foreign Agents Law.

Most of the election campaigns at the municipal level were focused on the local agenda and communal issues. The only significant anti‑war campaign was the nomination of a WWII Leningrad blockade survivor Lyudmila Vasilieva as a candidate for governor of St. Petersburg.

Her unequivocal and clearly articulated anti‑war position attracted many supporters and was echoed in independent media and social networks. Several thousand citizens of St. Petersburg came to support the candidate’s nomination, but these efforts were not enough to overcome the formal barriers to registration for the election.

In order to pass the so‑called “municipal filter,“ signatures of 10% of incumbent municipal deputies must be collected. Many independent municipal deputies were unable to provide a signature because they were illegally deprived of their mandate while in exile. The incumbent deputies in St. Petersburg often explained their refusal by fear of persecution.

9 out of the 59 Yabloko candidates who managed to register have been elected to municipal councils in Pskov (7), Ryazan (1), and Novgorod (1) Oblasts.

The government has responded to Yabloko’s success in Pskov Oblast with political repressions targeting the party’s regional leader Lev Shlosberg: on October 2, his apartment was searched as part of a criminal investigation of a violation of the Foreign Agents Law.

Most of the election campaigns at the municipal level were focused on the local agenda and communal issues. The only significant anti‑war campaign was the nomination of a WWII Leningrad blockade survivor Lyudmila Vasilieva as a candidate for governor of St. Petersburg.

Her unequivocal and clearly articulated anti‑war position attracted many supporters and was echoed in independent media and social networks. Several thousand citizens of St. Petersburg came to support the candidate’s nomination, but these efforts were not enough to overcome the formal barriers to registration for the election.

In order to pass the so‑called “municipal filter,” signatures of 10% of incumbent municipal deputies must be collected. Many independent municipal deputies were unable to provide a signature because they were illegally deprived of their mandate while in exile. The incumbent deputies in St. Petersburg often explained their refusal by fear of persecution.

For many citizens, voting itself was an opportunity to protest.

The most high‑profile case has occurred in St. Petersburg: an observer Marina Popova was taken to a police station for writing “No to War” on her ballot paper.

The police has documented violations of regulations on “disorderly conduct” and “discrediting the military”.

Ms. Popova allegedly violated public order with her sign, which was written in large letters and bright blue ink. She was fined 30,000 rubles and had to spend five days under arrest.

For many citizens, voting itself was an opportunity to protest.

The most high‑profile case has occurred in St. Petersburg: an observer Marina Popova was taken to a police station for writing “No to War” on her ballot paper.

The police has documented violations of regulations on “disorderly conduct” and “discrediting the military”.

Ms. Popova allegedly violated public order with her sign, which was written in large letters and bright blue ink. She was fined 30,000 rubles and had to spend five days under arrest.

The message of the Russian authorities is clear: no protest will go unpunished; no attempt to bring alternative options to any level of governance will yield results. The choice offered to activists and politicians is simple: leave or stay silent.

The message of the Russian authorities is clear: no protest will go unpunished; no attempt to bring alternative options to any level of governance will yield results. The choice offered to activists and politicians is simple: leave or stay silent.

The institution of elections in Russia has steadily eroded over the years, both, under administrative pressure, and through legislative change. Today, political activists, independent candidates and deputies, and the observer community are subjected to repression.

In 2024, those included by the state in the registers of “foreign agents”, “extremists,“ and “terrorists” were deprived of their electoral rights; among them are current deputies, scientists, public figures, journalists, and politically active citizens.

They are not allowed to be proxies and authorized representatives of candidates and electoral associations as well as observers (the ban forbidding “foreign agents” to become members of election commissions was established earlier).

Because of this legalized discrimination and criminal cases against civil society, the 2024 elections set anti‑records in terms of the number of people willing to participate in them.

The institution of elections in Russia has steadily eroded over the years, both, under administrative pressure, and through legislative change. Today, political activists, independent candidates and deputies, and the observer community are subjected to repression.

In 2024, those included by the state in the registers of “foreign agents”, “extremists,” and “terrorists” were deprived of their electoral rights; among them are current deputies, scientists, public figures, journalists, and politically active citizens.

They are not allowed to be proxies and authorized representatives of candidates and electoral associations as well as observers (the ban forbidding “foreign agents” to become members of election commissions was established earlier).

Because of this legalized discrimination and criminal cases against civil society, the 2024 elections set anti‑records in terms of the number of people willing to participate in them.

The parties began to act even more cautiously, seeking approval for significant nominations from the federal and/or regional administrations and giving up the territories where the government representatives were not in a strong position.

Golos has reported that nomination rates for governor candidates decreased almost 1.5 times compared to 2019. In regional parliamentary elections, an average of 6.3 party lists per region were nominated, the lowest figure since the 2012 party reform.

In single‑mandate constituencies, parties without preferential treatment nominated four times fewer candidates than there were mandates in regional parliaments. And there were half as many self‑nominated candidates as there were mandates.

The municipal filter remains an insurmountable barrier for candidates who can pose any threat (not only electoral, but also media and reputational) to the Kremlin’s nominees; opposition candidates must look disproportionately weaker than those approved by the officials.

The parties began to act even more cautiously, seeking approval for significant nominations from the federal and/or regional administrations and giving up the territories where the government representatives were not in a strong position.

Golos has reported that nomination rates for governor candidates decreased almost 1.5 times compared to 2019. In regional parliamentary elections, an average of 6.3 party lists per region were nominated, the lowest figure since the 2012 party reform.

In single‑mandate constituencies, parties without preferential treatment nominated four times fewer candidates than there were mandates in regional parliaments. And there were half as many self‑nominated candidates as there were mandates.

The municipal filter remains an insurmountable barrier for candidates who can pose any threat (not only electoral, but also media and reputational) to the Kremlin’s nominees; opposition candidates must look disproportionately weaker than those approved by the officials.

As a result, CPRF lost five people at the registration stage, A Just Russia lost three, and New People simply did not nominate candidates in 11 out of 21 regions.

St. Petersburg’s case, where all signatures for registered gubernatorial candidates were collected in two days, shows that the filter can only be passed with direct administrative support.

As a result, CPRF lost five people at the registration stage, A Just Russia lost three, and New People simply did not nominate candidates in 11 out of 21 regions.

St. Petersburg’s case, where all signatures for registered gubernatorial candidates were collected in two days, shows that the filter can only be passed with direct administrative support.

It is only at the level of local self‑governance that some elements of real political competition can still be found, although even there it is arbitrarily limited. In addition, many regions are undergoing municipal reforms aimed at the complete elimination of the settlement level of local self‑governance; the opportunities for citizens to participate in self‑governance are shrinking.

It is only at the level of local self‑governance that some elements of real political competition can still be found, although even there it is arbitrarily limited. In addition, many regions are undergoing municipal reforms aimed at the complete elimination of the settlement level of local self‑governance; the opportunities for citizens to participate in self‑governance are shrinking.

Fraud and falsification of voting results have long been commonplace in Russian elections.

Pro‑presidential candidates are protected from competitors, protesting citizens are demotivated, and the Kremlin is getting more effective at bringing supporters to the polling stations and creating the appearance of success.

However, massive denials of registration to independent candidates and poor coverage of election campaigns, with the exception of candidates of the “party of power,“ do reliably reduce the turnout. This time around, the authorities had to make additional efforts to make turnout and results look decent.

It is evident that all regions set turnout targets and percentages for the winning parties/candidates in advance.

For example, in some districts of St. Petersburg the observers discovered virtually identical voting results at dozens of the polling stations: the election commissions took the target figures released by the city administration quite literally.

Fraud and falsification of voting results have long been commonplace in Russian elections.

Pro‑presidential candidates are protected from competitors, protesting citizens are demotivated, and the Kremlin is getting more effective at bringing supporters to the polling stations and creating the appearance of success.

However, massive denials of registration to independent candidates and poor coverage of election campaigns, with the exception of candidates of the “party of power,” do reliably reduce the turnout. This time around, the authorities had to make additional efforts to make turnout and results look decent.

It is evident that all regions set turnout targets and percentages for the winning parties/candidates in advance.

For example, in some districts of St. Petersburg the observers discovered virtually identical voting results at dozens of the polling stations: the election commissions took the target figures released by the city administration quite literally.

In order to ensure a satisfactory turnout, government employees and employees of large government‑controlled corporations were bused in to the polls to vote, and additional polling stations, including extraterritorial ones, were used, along with home‑based and multi‑day voting.

Remote electronic voting, or DEG, deserves a special mention. Across Russia (not counting Moscow), 827,000 Russians voted electronically, as the Ministry of Finance reported.

The average “electronic” turnout was 90%, meaning that 90%, and in some regions 95% of pre‑registered voters voted. In Moscow, the DEG was dominant: according to official data, just over 3 million voters cast their ballots in the capital, only 142,000 of whom used paper ballots.

Voting by paper ballot was much more difficult than voting remotely, hampered by bureaucratic obstacles (for example, in Moscow it was necessary to submit an application for a paper ballot in advance, and many requested ballots were not received).

It’s not surprising that Golos' mathematical analysis of the voting results detected anomalies in most regions, indicating vote stuffing.

In order to ensure a satisfactory turnout, government employees and employees of large government‑controlled corporations were bused in to the polls to vote, and additional polling stations, including extraterritorial ones, were used, along with home‑based and multi‑day voting.

Remote electronic voting, or DEG, deserves a special mention. Across Russia (not counting Moscow), 827,000 Russians voted electronically, as the Ministry of Finance reported.

The average “electronic” turnout was 90%, meaning that 90%, and in some regions 95% of pre‑registered voters voted. In Moscow, the DEG was dominant: according to official data, just over 3 million voters cast their ballots in the capital, only 142,000 of whom used paper ballots.

Voting by paper ballot was much more difficult than voting remotely, hampered by bureaucratic obstacles (for example, in Moscow it was necessary to submit an application for a paper ballot in advance, and many requested ballots were not received).

It’s not surprising that Golos' mathematical analysis of the voting results detected anomalies in most regions, indicating vote stuffing.

Altogether, it allowed the ruling party to demonstrate acceptable and sometimes triumphant results. What remains out of sight is the inability of the Russian authorities to bring people to the polling stations and win the elections without administrative pressure, falsifications, and fraud. It is a poignant marker of the Russian reality.

Altogether, it allowed the ruling party to demonstrate acceptable and sometimes triumphant results. What remains out of sight is the inability of the Russian authorities to bring people to the polling stations and win the elections without administrative pressure, falsifications, and fraud. It is a poignant marker of the Russian reality.

Everything we know about elections in modern Russia we owe to the observer community, to activists and volunteers who are ready to be at polling stations 24 hours a day to fight for fair results.

The Russian state has long fought against independent observers, pushing them out under the pretext of “public control.”

Everything we know about elections in modern Russia we owe to the observer community, to activists and volunteers who are ready to be at polling stations 24 hours a day to fight for fair results.

The Russian state has long fought against independent observers, pushing them out under the pretext of “public control.”

In the last year, the rights of observers and members of election commissions were once again subjected to further legislative and procedural restrictions. This applies not only to the ability to take photos or make video recordings of violations and to move freely around a polling station, but also to the very possibility of being assigned to one.

In the wake of the June resolution of the Central Electoral Commission stating that each commission charged with organizing the elections should format observer lists independently, different regions came up with different obscure rules for drawing up documents.

This applies even to the font to be used when filling out the form electronically: in Moscow, for example, Times New Roman is mandatory, while commissions in the Sverdlovsk region require the use of Liberation Serif.

This gave the election commissions the right and opportunity to reject observer lists submitted by candidates and parties not affiliated with the authorities, of which they took full advantage.

In the last year, the rights of observers and members of election commissions were once again subjected to further legislative and procedural restrictions. This applies not only to the ability to take photos or make video recordings of violations and to move freely around a polling station, but also to the very possibility of being assigned to one.

In the wake of the June resolution of the Central Electoral Commission stating that each commission charged with organizing the elections should format observer lists independently, different regions came up with different obscure rules for drawing up documents.

This applies even to the font to be used when filling out the form electronically: in Moscow, for example, Times New Roman is mandatory, while commissions in the Sverdlovsk region require the use of Liberation Serif.

This gave the election commissions the right and opportunity to reject observer lists submitted by candidates and parties not affiliated with the authorities, of which they took full advantage.

During the voting period, there were reports from different regions that the election commissions refused to accept observers on formal grounds and sometimes prevented them from submitting documents for their appointment.

Some higher‑level election commissions simply failed to transmit lists of observers to precinct commissions. Excessive requirements for the registration of observer assignments to polling stations caused the disruption of party observation campaigns in entire regions.

Ekaterina Belyankina, an expert on observation, says that in 2019 she coordinated the work of 200 observers in one district of St. Petersburg, but this year only two independent observers were able to get to polling stations in the same district.

Pressure on the observer community does not only concern election observation processes. The observers are being persecuted.

During the voting period, there were reports from different regions that the election commissions refused to accept observers on formal grounds and sometimes prevented them from submitting documents for their appointment.

Some higher‑level election commissions simply failed to transmit lists of observers to precinct commissions. Excessive requirements for the registration of observer assignments to polling stations caused the disruption of party observation campaigns in entire regions.

Ekaterina Belyankina, an expert on observation, says that in 2019 she coordinated the work of 200 observers in one district of St. Petersburg, but this year only two independent observers were able to get to polling stations in the same district.

Pressure on the observer community does not only concern election observation processes. The observers are being persecuted.

Grigory Melkonyants, chairman of the Golos movement, has been in pre‑trial detention for 13 months; on the first day of voting, Golos board member David Kankiya was declared a “foreign agent.“ More than 20 Golos members have been labeled “foreign agents” and deprived of the right to participate in election observation.

Grigory Melkonyants, chairman of the Golos movement, has been in pre‑trial detention for 13 months; on the first day of voting, Golos board member David Kankiya was declared a “foreign agent.” More than 20 Golos members have been labeled “foreign agents” and deprived of the right to participate in election observation.

For more than a decade now, we see the Russian state not only tighten the legislation, but also illegally restrict the rights of the observers in order to conceal violations in the voting process. It evidences both the unfairness of elections and the effectiveness of the observer community.

For more than a decade now, we see the Russian state not only tighten the legislation, but also illegally restrict the rights of the observers in order to conceal violations in the voting process. It evidences both the unfairness of elections and the effectiveness of the observer community.

The authorities have many fears; they are afraid that they will not be able to ensure the necessary level of loyalty to the Kremlin and that the scale of falsifications will become obvious to the silent majority, causing discontent. Enforcing apathy and disengagement helps to keep the society under control.

Many experts believe that the regional elections are a precursor for the next State Duma elections in 2026.

The authorities have many fears; they are afraid that they will not be able to ensure the necessary level of loyalty to the Kremlin and that the scale of falsifications will become obvious to the silent majority, causing discontent. Enforcing apathy and disengagement helps to keep the society under control.

Many experts believe that the regional elections are a precursor for the next State Duma elections in 2026.

Next year, we should expect a widespread introduction of remote electronic voting, reduction of competition to a minimum, and more military veterans among the candidates. However, a lot is predicated on the outcome of the war in Ukraine and Putin’s ability to emerge victorious from it.

Civic and political activists who remain in Russia and those who help them from exile with their desperate actions are keeping Russian civil society a part of political. They need support of the democratic world.

Next year, we should expect a widespread introduction of remote electronic voting, reduction of competition to a minimum, and more military veterans among the candidates. However, a lot is predicated on the outcome of the war in Ukraine and Putin’s ability to emerge victorious from it.

Civic and political activists who remain in Russia and those who help them from exile with their desperate actions are keeping Russian civil society a part of political. They need support of the democratic world.

Do these elections still matter? What’s the best plan of action for the Russian prodemocracy forces for these elections?

By Vladimir Milov

February 06, 2024

Article

Article The most crucial message of his campaign to both the country and the world: there are numerous individuals in Russia who oppose this war, who oppose Putin

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

February 15, 2024

Article

Article By Roland Freudenstein

June 12, 2024

Do these elections still matter? What’s the best plan of action for the Russian prodemocracy forces for these elections?

By Vladimir Milov

February 06, 2024

Article

Article The most crucial message of his campaign to both the country and the world: there are numerous individuals in Russia who oppose this war, who oppose Putin

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

February 15, 2024

Article

Article By Roland Freudenstein

June 12, 2024