How infrastructure control works

A few examples from recent Russian history

By Alexander Zaritsky January 21, 2025

A few examples from recent Russian history

By Alexander Zaritsky January 21, 2025

The key to understanding modern autocracies lies in political routine. Among the numerous tools of oversight and control available to them, direct repression is a last resort. Today, authoritarian governments are primarily interested in establishing infrastructural power, i.e., the ability to maintain regular control.

If a state is unable to collect taxes, enforce laws, and accumulate even approximate information about its citizens, the existence of this state is meaningless, regardless of whether it works for the benefit of everyone or solely in the interest of the rulers.

A skilful application of infrastructural control methods can minimize direct repression and thereby negate the economic, logistical, and reputational costs of overt violence. The use of coercion is a sign that a government either does not care much about its reputation or must compensate for a lack of support with brutality.

The key to understanding modern autocracies lies in political routine. Among the numerous tools of oversight and control available to them, direct repression is a last resort. Today, authoritarian governments are primarily interested in establishing infrastructural power, i.e., the ability to maintain regular control.

If a state is unable to collect taxes, enforce laws, and accumulate even approximate information about its citizens, the existence of this state is meaningless, regardless of whether it works for the benefit of everyone or solely in the interest of the rulers.

A skilful application of infrastructural control methods can minimize direct repression and thereby negate the economic, logistical, and reputational costs of overt violence. The use of coercion is a sign that a government either does not care much about its reputation or must compensate for a lack of support with brutality.

Looking at the number of politically motivated criminal cases in recent years and the exorbitant severity of the sentences handed down, one can rightly conclude that the regime in Russia has transformed from a dictatorship of deceit to a dictatorship of fear. But the layer of “soft” control is still important because it affects millions of people in one way or another.

Traditionally, the most important instruments of infrastructural control are considered to be the bureaucracy and the police, which we will omit for the sake of more specific Russian subjects.

Looking at the number of politically motivated criminal cases in recent years and the exorbitant severity of the sentences handed down, one can rightly conclude that the regime in Russia has transformed from a dictatorship of deceit to a dictatorship of fear. But the layer of “soft” control is still important because it affects millions of people in one way or another.

Traditionally, the most important instruments of infrastructural control are considered to be the bureaucracy and the police, which we will omit for the sake of more specific Russian subjects.

A notable feature of the Russian political imagination is etatism: the notion that society and the state are a single entity, where the state should be the primary regulator of social life and guarantor of social support.

Authoritarian leaders often translate this position into a strategy of infrastructural control, known as clientelism or patron‑client relations.

The main democratic mechanism for creating legitimacy, winning an open political struggle, is not available to authoritarian leaders; they need alternative ways to attract popular support. Therefore, in non‑democratic countries, social protection measures have a dual function: it is a means of economic redistribution and social control. By redistributing resources in favor of certain groups of citizens, the government plays the role of a patron, and the supported groups become clients.

A notable feature of the Russian political imagination is etatism: the notion that society and the state are a single entity, where the state should be the primary regulator of social life and guarantor of social support.

Authoritarian leaders often translate this position into a strategy of infrastructural control, known as clientelism or patron‑client relations.

The main democratic mechanism for creating legitimacy, winning an open political struggle, is not available to authoritarian leaders; they need alternative ways to attract popular support. Therefore, in non‑democratic countries, social protection measures have a dual function: it is a means of economic redistribution and social control. By redistributing resources in favor of certain groups of citizens, the government plays the role of a patron, and the supported groups become clients.

Some researchers call social support the key to the survival of authoritarian regimes. The link between the fulfilment of social obligations and regime stability is quite strong and is often described as an informal social contract: the state provides jobs, benefits, and allowances in return for the loyalty of citizens.

In this way, the regime gains additional stability, elites, an opportunity to extract corrupt rents, and citizens, an improved quality of life (1, 2).

Moreover, in the case of the middle class, financial dependence on the state as an employer tangibly reduces the demand for democratization, which makes officials and employees of state corporations the base of support for the regime. Relatively well‑off public sector employees are less likely to support democratic reforms or participate in protests (1, 2).

Some researchers call social support the key to the survival of authoritarian regimes. The link between the fulfilment of social obligations and regime stability is quite strong and is often described as an informal social contract: the state provides jobs, benefits, and allowances in return for the loyalty of citizens.

In this way, the regime gains additional stability, elites, an opportunity to extract corrupt rents, and citizens, an improved quality of life (1, 2).

Moreover, in the case of the middle class, financial dependence on the state as an employer tangibly reduces the demand for democratization, which makes officials and employees of state corporations the base of support for the regime. Relatively well‑off public sector employees are less likely to support democratic reforms or participate in protests (1, 2).

This tool remains especially important in post‑communist countries, where citizens' expectations of the state’s social responsibility are quite pronounced.

In modern Russia, the support system is far from being as inclusive as in the USSR, but it is still as meaningful ideologically. The state is the direct or indirect employer of about 30% of the country’s population. Together with pensioners, this number reaches 45%, so it is important for the government to maintain at least the appearance of fighting for social justice.

In his addresses to the Federal Assembly, Vladimir Putin has periodically noted that Russia surpassed the USSR in terms of social obligations. In practice, however, there has been a steady decline in social spending. In 2018, Putin’s rating, which had soared after the annexation of Crimea, fell below its previous level.

This tool remains especially important in post‑communist countries, where citizens' expectations of the state’s social responsibility are quite pronounced.

In modern Russia, the support system is far from being as inclusive as in the USSR, but it is still as meaningful ideologically. The state is the direct or indirect employer of about 30% of the country’s population. Together with pensioners, this number reaches 45%, so it is important for the government to maintain at least the appearance of fighting for social justice.

In his addresses to the Federal Assembly, Vladimir Putin has periodically noted that Russia surpassed the USSR in terms of social obligations. In practice, however, there has been a steady decline in social spending. In 2018, Putin’s rating, which had soared after the annexation of Crimea, fell below its previous level.

To prevent a repetition of this situation, the government launched targeted, although reputationally successful national projects and reduced the expenditure items least visible to citizens. The social support system in its current form is quite selective (1, 2).

Apart from the already mentioned budgetary employees and employees of state corporations, its main beneficiaries are pensioners (important from the point of view of reputation and electoral prospects) and families with children (important from the point of view of human resources).

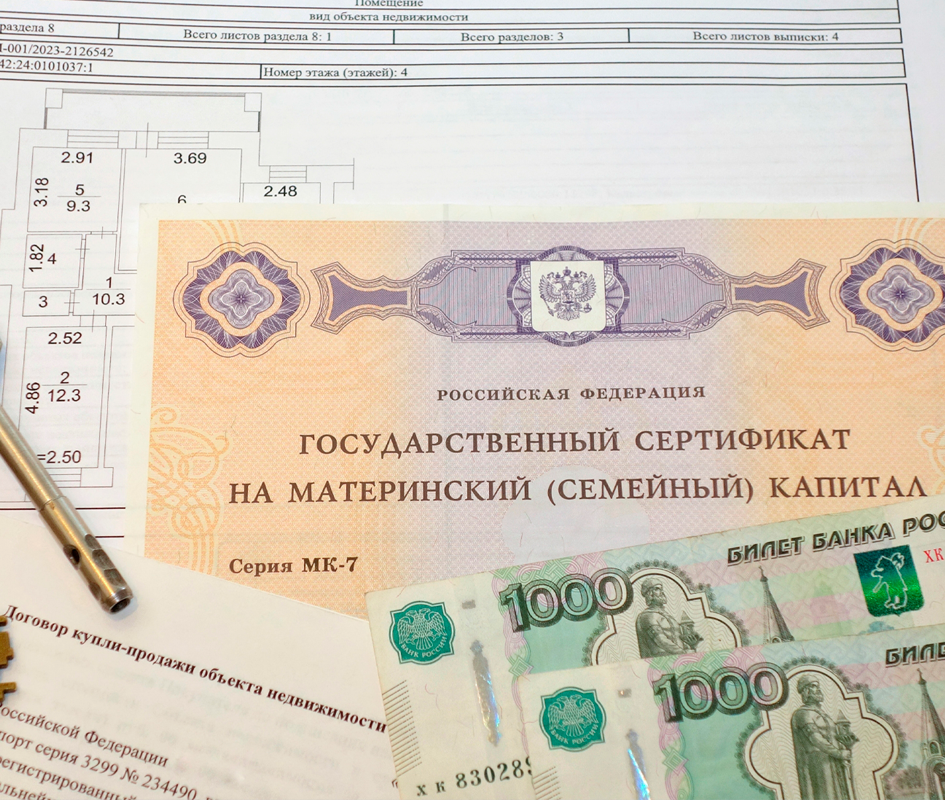

For example, the maternity capital program attracts support rather effectively. The president’s approval rating is generally higher among those who receive these payments, and we are talking about millions of families here. This, however, does not apply to the poorest: the amount of payments is too small to sustainably improve their quality of life, and therefore the fact of receiving benefits does not affect the level of approval in this group.

To prevent a repetition of this situation, the government launched targeted, although reputationally successful national projects and reduced the expenditure items least visible to citizens. The social support system in its current form is quite selective (1, 2).

Apart from the already mentioned budgetary employees and employees of state corporations, its main beneficiaries are pensioners (important from the point of view of reputation and electoral prospects) and families with children (important from the point of view of human resources).

For example, the maternity capital program attracts support rather effectively. The president’s approval rating is generally higher among those who receive these payments, and we are talking about millions of families here. This, however, does not apply to the poorest: the amount of payments is too small to sustainably improve their quality of life, and therefore the fact of receiving benefits does not affect the level of approval in this group.

Patron‑client relationships can also be more asymmetrical, as in the case of schoolteachers. Teachers are firmly embedded in the everyday life of many Russians and are more trusted than other budgetary employees (officials or police officers). At the same time, most of them are completely dependent on state funding.

Hence the constant use of teachers to rig elections and spread propaganda without substantial bonuses in return. The very possibility of working in a school becomes a bargaining chip, making an entire professional group a hostage to the state.

Clientelism would be an ideal control mechanism if it did not have the critical disadvantage of being expensive. By and large, the social contract that had existed since Putin’s first term was undermined by the pension reform and the government’s limp response to the COVID‑19 pandemic amid economic instability.

Patron‑client relationships can also be more asymmetrical, as in the case of schoolteachers. Teachers are firmly embedded in the everyday life of many Russians and are more trusted than other budgetary employees (officials or police officers). At the same time, most of them are completely dependent on state funding.

Hence the constant use of teachers to rig elections and spread propaganda without substantial bonuses in return. The very possibility of working in a school becomes a bargaining chip, making an entire professional group a hostage to the state.

Clientelism would be an ideal control mechanism if it did not have the critical disadvantage of being expensive. By and large, the social contract that had existed since Putin’s first term was undermined by the pension reform and the government’s limp response to the COVID‑19 pandemic amid economic instability.

Social support became even more selective due to a surge in spending on war. In 2025, military spending will account for about 40% of all planned federal budget expenditures; payments to new contractors, wounded, and families of the dead are already taking up a large part of the social support budget in some regions.

The astronomical payments and other support measures, such as debt forgiveness, credit vacations, and the role of a new elite promised to veterans, are designed to increase the attractiveness of military service and postpone a new wave of mobilization.

War veterans have become the only group that is truly important to the state, and the system of social support has turned into a system for hiring mercenaries.

On the one hand, this makes it possible to maintain record rates of recruitment. On the other hand, the effectiveness of this strategy is limited. The size of payments cannot be increased indefinitely; few people are willing to risk their lives for any amount of money. Sooner or later the limit will be reached, and the authorities will have to return to the issue of mobilization.

Social support became even more selective due to a surge in spending on war. In 2025, military spending will account for about 40% of all planned federal budget expenditures; payments to new contractors, wounded, and families of the dead are already taking up a large part of the social support budget in some regions.

The astronomical payments and other support measures, such as debt forgiveness, credit vacations, and the role of a new elite promised to veterans, are designed to increase the attractiveness of military service and postpone a new wave of mobilization.

War veterans have become the only group that is truly important to the state, and the system of social support has turned into a system for hiring mercenaries.

On the one hand, this makes it possible to maintain record rates of recruitment. On the other hand, the effectiveness of this strategy is limited. The size of payments cannot be increased indefinitely; few people are willing to risk their lives for any amount of money. Sooner or later the limit will be reached, and the authorities will have to return to the issue of mobilization.

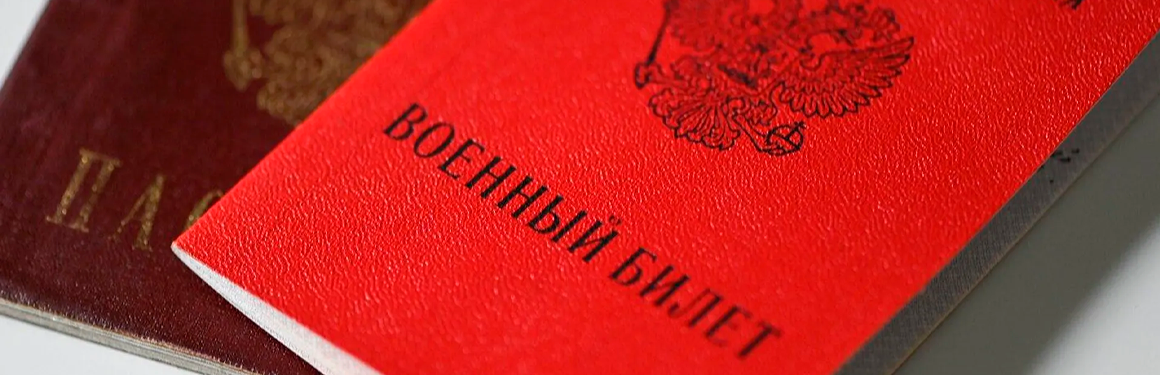

The infrastructure is being prepared for this moment. The electronic register of summonses launched in the test mode is not in use yet, but it opens a possibility of continuing hidden mobilization.

In 2024, traditional methods of compulsion were actively employed: mass raids on conscripts and urgent dispatches to the troops became more frequent. Electronic summonses will not help to conceal or replace these unpopular measures but will allow for them to be applied more precisely.

Once the automatic ban on travel abroad is in place, it will become even more difficult to avoid mobilization or forced signing of a contract. Additional problems are created by the increased attention of supervisory agencies to the diligence with which employers keep military records. In this way, the state gives employers a supervisory function, at the same time cheapening and tightening day‑to-day control.

The infrastructure is being prepared for this moment. The electronic register of summonses launched in the test mode is not in use yet, but it opens a possibility of continuing hidden mobilization.

In 2024, traditional methods of compulsion were actively employed: mass raids on conscripts and urgent dispatches to the troops became more frequent. Electronic summonses will not help to conceal or replace these unpopular measures but will allow for them to be applied more precisely.

Once the automatic ban on travel abroad is in place, it will become even more difficult to avoid mobilization or forced signing of a contract. Additional problems are created by the increased attention of supervisory agencies to the diligence with which employers keep military records. In this way, the state gives employers a supervisory function, at the same time cheapening and tightening day‑to-day control.

Not so long ago, the phrase “student protest” sounded quite casual in Russia: in the 1990s, the vigorous political activity of students was one of the levers of the academic community’s influence on the state.

In the second half of the 2000s, the situation changed: programs of institutional support for universities emerged, protecting the strongest ones from market risks by budget money. Thus, the state dealt an indirect blow to the autonomy of universities. In most cases, financial support is not guaranteed and depends on universities meeting standards set and observed by the government.

This approach makes it possible to arbitrarily reduce the amount of support for universities, whose management fails to control the political activity of students and staff.

Not so long ago, the phrase “student protest” sounded quite casual in Russia: in the 1990s, the vigorous political activity of students was one of the levers of the academic community’s influence on the state.

In the second half of the 2000s, the situation changed: programs of institutional support for universities emerged, protecting the strongest ones from market risks by budget money. Thus, the state dealt an indirect blow to the autonomy of universities. In most cases, financial support is not guaranteed and depends on universities meeting standards set and observed by the government.

This approach makes it possible to arbitrarily reduce the amount of support for universities, whose management fails to control the political activity of students and staff.

Less prestigious universities were left to fight for their own survival; as a result, the academic community was split between “rich” and “poor” universities.

In addition, the Ministry of Science and Higher Education has a more direct way of intimidating them. Since funding is contingent on the number of state‑funded places, unwanted institutions can be punished at any time by reducing quotas.

The election of rectors was effectively abolished due to a change in the procedure in 2006, after which all potential candidates had to be approved before elections. Rectors of key universities are now directly appointed by the government or line ministries. These changes provoked protests from the academic community but were carried out with little public scrutiny and without direct involvement of law enforcement agencies or high‑profile criminal cases.

Less prestigious universities were left to fight for their own survival; as a result, the academic community was split between “rich” and “poor” universities.

In addition, the Ministry of Science and Higher Education has a more direct way of intimidating them. Since funding is contingent on the number of state‑funded places, unwanted institutions can be punished at any time by reducing quotas.

The election of rectors was effectively abolished due to a change in the procedure in 2006, after which all potential candidates had to be approved before elections. Rectors of key universities are now directly appointed by the government or line ministries. These changes provoked protests from the academic community but were carried out with little public scrutiny and without direct involvement of law enforcement agencies or high‑profile criminal cases.

The 2010s became a time of pinpoint bureaucratic pressure on private universities (and some units of state universities) under the guise of increasing the quality of education. In 2016, EUSPB lost its accreditation for a while, and in 2017, its license. In 2018, Rosobrnadzor revoked the accreditation of MVSESEN (“Shaninka”) for two years.

The summer of 2019 saw a high‑profile scandal at the Higher School of Economics, during which respected academics were forced to uphold the meme‑like thesis “the university is outside of politics” to demonstrate their loyalty. Faculty dismissals were rarely mass, most often presented as non‑renewal of short‑term contracts on formal grounds.

The situation deteriorated sharply in 2021, when inspections were followed by criminal cases, foreign partners were recognized as “undesirable organizations,” and teachers were labelled as “foreign agents.”

In 2022, coerced by law enforcement agencies, entire educational programs were completely reformatted or closed, and publicly expressing an anti‑war stance would result in dismissal or expulsion.

The 2010s became a time of pinpoint bureaucratic pressure on private universities (and some units of state universities) under the guise of increasing the quality of education. In 2016, EUSPB lost its accreditation for a while, and in 2017, its license. In 2018, Rosobrnadzor revoked the accreditation of MVSESEN (“Shaninka”) for two years.

The summer of 2019 saw a high‑profile scandal at the Higher School of Economics, during which respected academics were forced to uphold the meme‑like thesis “the university is outside of politics” to demonstrate their loyalty. Faculty dismissals were rarely mass, most often presented as non‑renewal of short‑term contracts on formal grounds.

The situation deteriorated sharply in 2021, when inspections were followed by criminal cases, foreign partners were recognized as “undesirable organizations,” and teachers were labelled as “foreign agents.”

In 2022, coerced by law enforcement agencies, entire educational programs were completely reformatted or closed, and publicly expressing an anti‑war stance would result in dismissal or expulsion.

While it is still possible to ensure the obedience of school and university teachers through joint efforts of law enforcement agencies, managers of educational institutions, whistleblowers, and Z‑activists, there are difficulties with school and university students.

The power of the repressive apparatus is not unlimited; it is simply impossible to track down all dissenters, especially if dissent is hardly ever voiced publicly. The Russian government is trying to get around this obstacle by introducing propaganda into educational programs, such as “Talking about Important Things” in schools and “Foundations of Russian Statehood” (as well as a number of other courses) at universities.

There is, of course, nothing “soft” about direct indoctrination attempts. Their effectiveness in convincing young people raises serious doubts, yet crude propaganda, oddly enough, can be an instrument of covert control. Confronting the overtly pro‑government content of new courses can be demoralizing, signalling the strength of the regime and thereby reducing young people’s inclination to protest.

While it is still possible to ensure the obedience of school and university teachers through joint efforts of law enforcement agencies, managers of educational institutions, whistleblowers, and Z‑activists, there are difficulties with school and university students.

The power of the repressive apparatus is not unlimited; it is simply impossible to track down all dissenters, especially if dissent is hardly ever voiced publicly. The Russian government is trying to get around this obstacle by introducing propaganda into educational programs, such as “Talking about Important Things” in schools and “Foundations of Russian Statehood” (as well as a number of other courses) at universities.

There is, of course, nothing “soft” about direct indoctrination attempts. Their effectiveness in convincing young people raises serious doubts, yet crude propaganda, oddly enough, can be an instrument of covert control. Confronting the overtly pro‑government content of new courses can be demoralizing, signalling the strength of the regime and thereby reducing young people’s inclination to protest.

Efforts to create a unified register of subpoenas are a logical step towards greater transparency of citizens in the eyes of the state. Against the background of a long‑standing trend towards the digitalization of government services in Russia, the idea of electronic subpoenas appears even a little belated. But the main operators of digital oversight in Russia, as in the global world, are technology companies.

Efforts to create a unified register of subpoenas are a logical step towards greater transparency of citizens in the eyes of the state. Against the background of a long‑standing trend towards the digitalization of government services in Russia, the idea of electronic subpoenas appears even a little belated. But the main operators of digital oversight in Russia, as in the global world, are technology companies.

As social networks and digital services become more widespread, the ability of IT corporations to collect user data expands, and this data eventually becomes a major source of revenue.

This is how the economic system called surveillance, digital, or information capitalism is born. The Russian market is not lagging behind the world in this respect, the difference being that the Russian version of surveillance capitalism was born with the active participation of the state.

The main player here is Sber, which has transformed from a relic of the Soviet era into a technological ecosystem. Although Yandex and VK Group use similar strategies, Sber’s position is unique. It is not only a taxi service, a music service, an online marketplace, etc., but also a state‑controlled bank with the country’s largest customer base, where many citizens receive their salaries and social payments. It has direct access to citizens' personal financial data, including the smallest everyday transactions, in addition to biometric data, geolocation, contacts, and so on.

As social networks and digital services become more widespread, the ability of IT corporations to collect user data expands, and this data eventually becomes a major source of revenue.

This is how the economic system called surveillance, digital, or information capitalism is born. The Russian market is not lagging behind the world in this respect, the difference being that the Russian version of surveillance capitalism was born with the active participation of the state.

The main player here is Sber, which has transformed from a relic of the Soviet era into a technological ecosystem. Although Yandex and VK Group use similar strategies, Sber’s position is unique. It is not only a taxi service, a music service, an online marketplace, etc., but also a state‑controlled bank with the country’s largest customer base, where many citizens receive their salaries and social payments. It has direct access to citizens' personal financial data, including the smallest everyday transactions, in addition to biometric data, geolocation, contacts, and so on.

Sber has the most complete digital profiles of Russians and shares them with government agencies as needed, under the guise of improving the quality of life through “neutral” technological solutions. The obsession with services has greatly increased users' tolerance for personal data collection.

This is quite problematic even in countries where IT corporations are not connected to the state, but in Russia, where popular banks, social networks, and delivery services are, for all intents and purposes, state‑controlled, the situation looks particularly dangerous.

While in other spheres law enforcers and technocrats were competing with each other, in the digital environment their goals unexpectedly coincided. Unwittingly, the innovators were on the Kremlin’s side. Now Alice is going to go where the security services would never think of going.

Sber has the most complete digital profiles of Russians and shares them with government agencies as needed, under the guise of improving the quality of life through “neutral” technological solutions. The obsession with services has greatly increased users' tolerance for personal data collection.

This is quite problematic even in countries where IT corporations are not connected to the state, but in Russia, where popular banks, social networks, and delivery services are, for all intents and purposes, state‑controlled, the situation looks particularly dangerous.

While in other spheres law enforcers and technocrats were competing with each other, in the digital environment their goals unexpectedly coincided. Unwittingly, the innovators were on the Kremlin’s side. Now Alice is going to go where the security services would never think of going.

Experiments with digital governance in Russia had begun long before Sber became a digital giant. The Gosuslugi service was launched in 2009 and gradually turned from an online directory to the core of the government’s digital ecosystem.

In 2024, interaction with Gosuslugi services is an almost inevitable prerequisite for access to routine bureaucratic operations and government support. A key moment of this transformation was the pandemic: the experience of using QR codes in combination with video surveillance to control the movement of citizens clearly was to the state’s liking.

Given the sharply negative reaction of Russians to covid restrictions, the Kremlin is unlikely to introduce a comprehensive social monitoring system. Nevertheless, the state will continue to penetrate everyday life to the best of its ability, including — thanks to IT corporations — those areas that were impossible to penetrate in the pre‑digital era.

The advantage of digital surveillance methods is that they allow the state to easily identify dissenters and monitor them without attracting undue attention.

Automated social media monitoring, spyware, hacking, facial recognition, geolocation tracking, and other digital surveillance tools are reputationally and economically cheaper than detention, interrogation, and external surveillance.

Digital surveillance helps to better control citizens in both virtual and physical spaces. Even the seemingly innocuous requirement to verify a phone number to use public Wi‑Fi can make it relatively easy to link that number to a specific location and, if necessary, to specific online activities.

Experiments with digital governance in Russia had begun long before Sber became a digital giant. The Gosuslugi service was launched in 2009 and gradually turned from an online directory to the core of the government’s digital ecosystem.

In 2024, interaction with Gosuslugi services is an almost inevitable prerequisite for access to routine bureaucratic operations and government support. A key moment of this transformation was the pandemic: the experience of using QR codes in combination with video surveillance to control the movement of citizens clearly was to the state’s liking.

Given the sharply negative reaction of Russians to covid restrictions, the Kremlin is unlikely to introduce a comprehensive social monitoring system. Nevertheless, the state will continue to penetrate everyday life to the best of its ability, including — thanks to IT corporations — those areas that were impossible to penetrate in the pre‑digital era.

The advantage of digital surveillance methods is that they allow the state to easily identify dissenters and monitor them without attracting undue attention.

Automated social media monitoring, spyware, hacking, facial recognition, geolocation tracking, and other digital surveillance tools are reputationally and economically cheaper than detention, interrogation, and external surveillance.

Digital surveillance helps to better control citizens in both virtual and physical spaces. Even the seemingly innocuous requirement to verify a phone number to use public Wi‑Fi can make it relatively easy to link that number to a specific location and, if necessary, to specific online activities.

The Runet, which, in the Kremlin’s logic, should be Russia’s “sovereign territory” in virtual space, is no less successfully controlled (see Ilona Stadnik, “Russia: An Independent and Sovereign Internet?” in Power and Authority in Internet Governance (Routledge, 2021).

Attempts to land popular social networks have predictably failed, so in recent years the Russian government has shifted to a Chinese‑like strategy. Most Western services have been blocked, and the Kremlin‑controlled VK has become the main social network.

Due to huge propaganda budgets, Russian‑language Telegram has been transformed from an opposition space into one teeming with Z‑channels with hundreds of thousands of subscribers. Blockades combined with the flooding of the remaining platforms with propaganda have created a media environment that is quite comfortable for the state.

Such “soft” control (as opposed to, for example, a complete shutdown of the Internet in Russia or criminal prosecution for the mere fact of access to banned information) is practical in that it causes less reputational damage, and yet it steers all but a relative minority of stubborn users in the right direction.

The Runet, which, in the Kremlin’s logic, should be Russia’s “sovereign territory” in virtual space, is no less successfully controlled (see Ilona Stadnik, “Russia: An Independent and Sovereign Internet?” in Power and Authority in Internet Governance (Routledge, 2021).

Attempts to land popular social networks have predictably failed, so in recent years the Russian government has shifted to a Chinese‑like strategy. Most Western services have been blocked, and the Kremlin‑controlled VK has become the main social network.

Due to huge propaganda budgets, Russian‑language Telegram has been transformed from an opposition space into one teeming with Z‑channels with hundreds of thousands of subscribers. Blockades combined with the flooding of the remaining platforms with propaganda have created a media environment that is quite comfortable for the state.

Such “soft” control (as opposed to, for example, a complete shutdown of the Internet in Russia or criminal prosecution for the mere fact of access to banned information) is practical in that it causes less reputational damage, and yet it steers all but a relative minority of stubborn users in the right direction.

Compared to China’s Internet control system, Russia’s is more decentralized; responsibility for digital control falls on ISPs. Technically, blocking and monitoring of traffic is ensured by their network infrastructure, which means that losses are primarily borne by ISPs, while the benefits accrue to the state.

Formal control capabilities are also dispersed: in total, there are more than a dozen agencies that have the authority to block websites. This can be explained by the fact that the Runet originally developed relatively freely, and the current configuration of regulatory tools was created gradually and ad hoc. In this respect, the situation in the digital environment resembles what happened a little earlier with traditional media.

The state continues to use the techniques tried and tested in television and print media. Telecommunications assets are amassed by those close to the Kremlin (the top 5 largest providers, including the leader — state‑owned Rostelecom — occupy more than ⅔ of the market).

The pressure on online media was finally replaced by outright censorship in 2022. 2,5 years after the introduction of military censorship, Russia is second only to Iran, China, and Myanmar in terms of Internet unfreedom.

Compared to China’s Internet control system, Russia’s is more decentralized; responsibility for digital control falls on ISPs. Technically, blocking and monitoring of traffic is ensured by their network infrastructure, which means that losses are primarily borne by ISPs, while the benefits accrue to the state.

Formal control capabilities are also dispersed: in total, there are more than a dozen agencies that have the authority to block websites. This can be explained by the fact that the Runet originally developed relatively freely, and the current configuration of regulatory tools was created gradually and ad hoc. In this respect, the situation in the digital environment resembles what happened a little earlier with traditional media.

The state continues to use the techniques tried and tested in television and print media. Telecommunications assets are amassed by those close to the Kremlin (the top 5 largest providers, including the leader — state‑owned Rostelecom — occupy more than ⅔ of the market).

The pressure on online media was finally replaced by outright censorship in 2022. 2,5 years after the introduction of military censorship, Russia is second only to Iran, China, and Myanmar in terms of Internet unfreedom.

Once upon a time, rulers used direct violence because there were no other methods of governance; the level of state intrusion was insignificant. Modern repression, on the other hand, is made possible by excessive, unrestrained infrastructural control.

It used to take a giant security apparatus to keep track of millions of people. Today, automated surveillance using big data may require no human involvement at all, making anyone within reach of the state apparatus susceptible to be monitored.

Paradoxically, this has not made autocrats any softer; quite the opposite. Surveillance infrastructures of modern states allow for more fine‑tuned repression, making it smaller but more intense (see Erica Frantz, Andrea Kendall‑Taylor, and Joseph Wright, “Digital Repression in Autocracies” in V‑Dem Users Working Paper 27).

The authoritarian state of the 21st century is first and foremost an infrastructurally strong control machine, capable of zeroing in on anything at any moment. There are two ways to escape from it: either to be out of its reach or not to be of any interest to it.

Once upon a time, rulers used direct violence because there were no other methods of governance; the level of state intrusion was insignificant. Modern repression, on the other hand, is made possible by excessive, unrestrained infrastructural control.

It used to take a giant security apparatus to keep track of millions of people. Today, automated surveillance using big data may require no human involvement at all, making anyone within reach of the state apparatus susceptible to be monitored.

Paradoxically, this has not made autocrats any softer; quite the opposite. Surveillance infrastructures of modern states allow for more fine‑tuned repression, making it smaller but more intense (see Erica Frantz, Andrea Kendall‑Taylor, and Joseph Wright, “Digital Repression in Autocracies” in V‑Dem Users Working Paper 27).

The authoritarian state of the 21st century is first and foremost an infrastructurally strong control machine, capable of zeroing in on anything at any moment. There are two ways to escape from it: either to be out of its reach or not to be of any interest to it.

If bureaucracies are transparent and accountable to citizens, public infrastructure works for the common good. Effective day‑to-day control is the foundation on which both a decent life for citizens and a military dictatorship can be built with equal success. Until recently, Russia was a country with a bifurcated system of governance: archaic law enforcers and corrupt bureaucracy neighboring with progressive technocrats from among the “system liberals.”

The institutions that support the everyday stability of Putin’s regime and create its repressive potential — the social support system, education, and digital services — were created by the progressive wing. The architects of these institutions made the critical mistake of thinking that good intentions justified working for an authoritarian government. As a result, the cutting edge of modernization turned out to be the facade of a repressive system.

If bureaucracies are transparent and accountable to citizens, public infrastructure works for the common good. Effective day‑to-day control is the foundation on which both a decent life for citizens and a military dictatorship can be built with equal success. Until recently, Russia was a country with a bifurcated system of governance: archaic law enforcers and corrupt bureaucracy neighboring with progressive technocrats from among the “system liberals."

The institutions that support the everyday stability of Putin’s regime and create its repressive potential — the social support system, education, and digital services — were created by the progressive wing. The architects of these institutions made the critical mistake of thinking that good intentions justified working for an authoritarian government. As a result, the cutting edge of modernization turned out to be the facade of a repressive system.

The evolution of Russian political system in 2024

By Vasiliy Zharkov

By Alexander Zaritsky

December 27, 2024

Article

Article By Natalia Savelyeva

December 23, 2024

Report

Report Prospects for Political Decentralization in Russia

By Irina Busygina

By Mikhail Filippov

May 29, 2024

The evolution of Russian political system in 2024

By Vasiliy Zharkov

By Alexander Zaritsky

December 27, 2024

Article

Article By Natalia Savelyeva

December 23, 2024

Report

Report Prospects for Political Decentralization in Russia

By Irina Busygina

By Mikhail Filippov

May 29, 2024