Russian State Duma Election

Assessment of the Election Results

By Sergey Bespalov October 27, 2021

Assessment of the Election Results

By Sergey Bespalov October 27, 2021

Assessment of the Election Results

Russia’s State Duma elections have been declared valid and the Central Election Commission (CEC) has shared the final results. Seats in the State Duma are now distributed as follows:

Compared with the 2016 elections, United Russia lost 19 seats, the CPRF gained 15 seats, and A Just Russia gained 4 seats. Meanwhile, the LDPR lost 18 seats, New People, which did not exist in 2016, gained 13 seats, self‑nominated candidates gained four seats, and the Growth Party, which did not have any seats in the Duma in 2016 gained one seat, while Rodina and Civic Platform continued to hold onto one seat each, which was no change from 2016.

United Russia has managed to retain its so‑called “constitutional majority” in the Duma, making it possible to initiate the process of changing the Russian Constitution by voting as a single block (constitutional changes require at least a two‑thirds vote in the State Duma, after which amendments are approved by the Federation Council before they are ratified by the legislative assemblies of the regions). The United Russia party faction has enough deputies that it does not need to find allies from among other factions in order to hold such a vote. Thusly, during its previous session, the constitutional amendment adopted on July 1, 2020 was then confirmed by the State Duma because the United Russia faction already had enough votes to do this on its own.

From the opposition’s perspective, however, the playing field looks drastically different compared to 2016. Then, the CPRF and populist‑nationalist LDPR received roughly the same number of votes (about 13% each), while the center‑left A Just Russia had just 6.2%. However, approval for United Russia suddenly plummeted in 2018 following a pension reform, just as support for the CPRF began to spike. From 2019 to 2021, the authorities launched an open, public attack on the CPRF, with about 40 Communist deputies in the regions having been subjected to criminal or administrative prosecution.

There has not much “communist” left about the CPRF, and today, it is simply an ordinary left‑wing party that tries to benefit from a significant historical brand recognition. In the face of a de‑facto ban on registering any new political parties in Russia without the Kremlin’s stamp of approval, the CPRF has found itself without any real political rivals as Russia’s only “left‑wing party”. In fact, large numbers of active left‑leaning voters have now become CPRF members and activists. Today’s CPRF has no qualms with the notion of private property, advocates for expanding the powers of parliaments at all levels, and supports the protection of political competition, expanding civil rights protections, and frequently supports civic initiatives (the Stop Shies movement in Arkhangelsk Oblast was one striking example of this, as was the Party’s “Statement 45” against political repression in Moscow following the 2019 Moscow City Duma elections).

As a parliamentary party, the CPRF has the advantage of registering candidates without having to gather signatures, which is why many local opposition activists, human rights activists, and others are most often nominated through the CPRF. This privilege extends to registering candidates for elections at all levels. Russia’s electoral system has two options: candidates are nominated by parties and “self‑nomination.” Self‑nomination is quite challenging as it involves verification of each voter signature submitted in support of a candidate, making it possible for the authorities to arbitrarily dismiss signatures as invalid.

This is why, CPRF’s privilege draws a lot of supporters who have sensibly concluded that they have no other avenues for registering for elections. For example, after Oleg Mikhailov was elected to the Russian State Duma on September 19, 2021 from a single‑mandate district in Komi, according to the CPRF list in the Komi State Council, his seat was given to Libertarian V. Vorobyov, who the CPRF had previously nominated on its list, along with other local activists (Vorobyov was the first Libertarian in Russia to become a regional deputy).

The Kremlin’s intensifying crack down on the CPRF has only strengthened the protest electorate’s rallying around the Party, and it has emerged as the leader in the opposition field. Elimination of former presidential candidate Pavel Grudinin from the CPRF’s list for the State Duma was one notable example of this. Grudinin was the Party’s de‑facto second in command, and a one‑time presidential candidate for the CPRF. He finished second in the elections, and enjoys wide popularity among voters. Gennady Zyuganov has been the Party’s permanent leader since 1994. Grudinin was accused of allegedly failing to close an offshore account in Belize in 2018, though the CPRF has claimed that all of the “evidence” of this is forged, and even presented the original documents itself. Moreover, the circumstances were no different when Grudinin was allowed to register as a presidential candidate in 2018.

According to official data, the CPRF received 18.93% of the vote in 2021 (57 seats—48 of which are from the electoral lists, and 9 from the districts). In protest regions, it received a similar number of votes to United Russia, winning in Yakutia, Khabarovsk Krai, Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Mari El Republic, and in many major cities (Vladivostok, Omsk, Syktyvkar, South Sakhalin, etc.). In 2016, United Russia won every region.

The LDPR has gone through a sudden decline, which is related to the fact that the party failed to defend its member —a highly popular governor of Khabarovsk Krai, Sergei Furgal, who was arrested in July 2020 over a conflict with Presidential Plenipotentiary Envoy Yuri Trutnev. The Far East has always been the LDPR’s electoral base.

Party leader Vladimir Zhirinovsky, who turned 75 last spring, is now quite elderly and has long stopped traveling to the regions. During the debates, he was forced to make feeble excuses for handing over Furgal. From 2000 to 2021, the LDPR’s number two was Zhirinovsky’s publicity‑shy son, Igor Lebedev (Zhirinovsky was the vice speaker of the State Duma, while his son was the faction leader), though in practice, Lebedev has led the party for some time. Lebedev did not even run in the 2021 elections, and the LDPR is now openly discussing new leadership. As a result, the party lost nearly half of its previous votes, receiving just 7.55% (21 seats—19 from the party list, and just two from the regions), and even its strong single mandate candidates appear to be underperforming.

Prior to the elections, A Just Russia had merged with two ultra nationalist parties—Gennady Semigin’s Patriots of Russia and Zakhar Prilepin’s For Truth. This drove some moderate supporters away (to the New People party in particular). At the same time, the party organized a wide‑ranging publicity campaign that tackled mainstream social and community issues, while staying away from ultra‑patriotist narratives. In the end, despite United Russia’s falling approval rating, A Just Russia’s share of the votes barely grew at all—7.46% compared to 6.22% (27 seats, 19 from the party list and 8 from the regions).

In addition to the CPRF’s sudden growth among the opposition, the LDPR’s decline, and A Just Russia’s stagnation, one more important election result is a new party entering parliament for the first time in 17 years. The New People party was created by Alexei Nechaev, the head of Faberlic cosmetics company, in early 2020. The authorities allowed the emergence of this new moderately liberal party with the goal of giving opposition‑minded urban educated voters at least some opportunity for political representation. Charismatic former mayor of Yakutsk Sardana Avksenteva, who was forced to resign in January 2021, became the second candidate on the New People list. Most of the other candidates on the party list were not particularly well‑known (the party even had to resort to YouTube‑based campaigns for recruitment).

In the summer of 2020, New People launched a massive campaign in the regions—newspapers, billboards, LED boards, etc. As the campaigning period came to a close, New People was among the top three parties that received the most mentions on television, and those mentions were always positive (whereas all mentions of the CPRF were negative). As a result, New People obtained 5.32% of the votes and 13 seats from the party list. In regions with high levels of election fraud (as detailed below), it barely received any votes, compared to 8%-10% in protest regions. Now, for the first time since the early 2000s, parliament has a fifth party, which is politically more right‑wing than United Russia (since 2003, all of Russia’s opposition has actually been to the left of United Russia).

Campaigns in majoritarian districts played out completely differently from those of 2016. The 2016 election was a rigged match, with just a thin veneer of competition, and the ruling party handing a few districts to the systemic opposition—out of 225 districts, in 19, United Russia did not even bother to nominate candidates. When all was said and done, United Russia won 203 districts (in other words, its candidates only lost in three precincts). This time, the districts were not divided up. Initially, United Russia only vacated five districts, with three more following later. Essentially, the districts were not won by the opposition, but by administrative self‑nominated candidates. United Russia still won 198 districts, meaning that its candidates lost in 19 districts, rather than just three. In all of the districts where the opposition parties did win, they faced tough battles. The opposition only lost 20 districts due to fraud.

Thus, the campaigns in 2016 and 2021 were quite different.

The coronavirus pandemic and its repercussions were a constant theme throughout the campaign. Under the pretext of “public health measures,” the Russian authorities banned all public opposition rallies, no matter how small, while still allowing several massive rallies organized by the governing party.

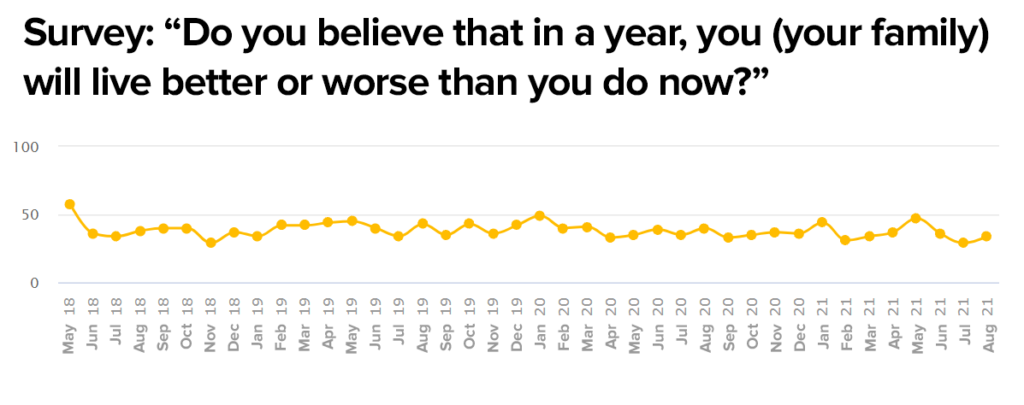

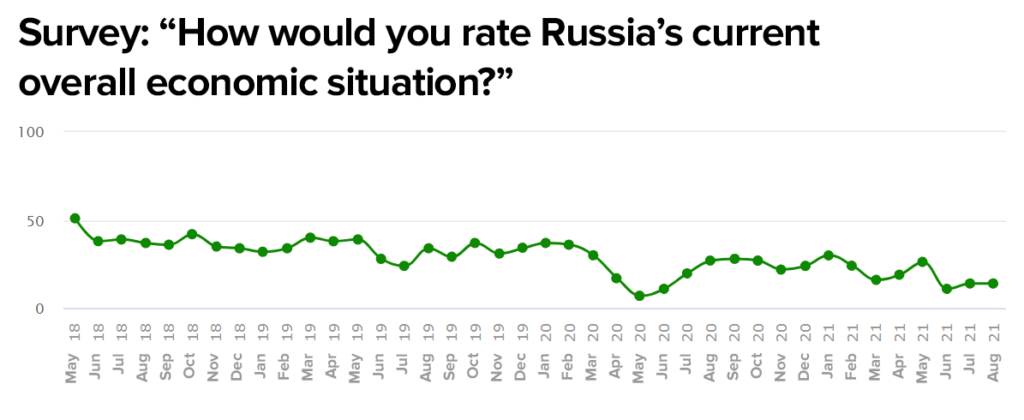

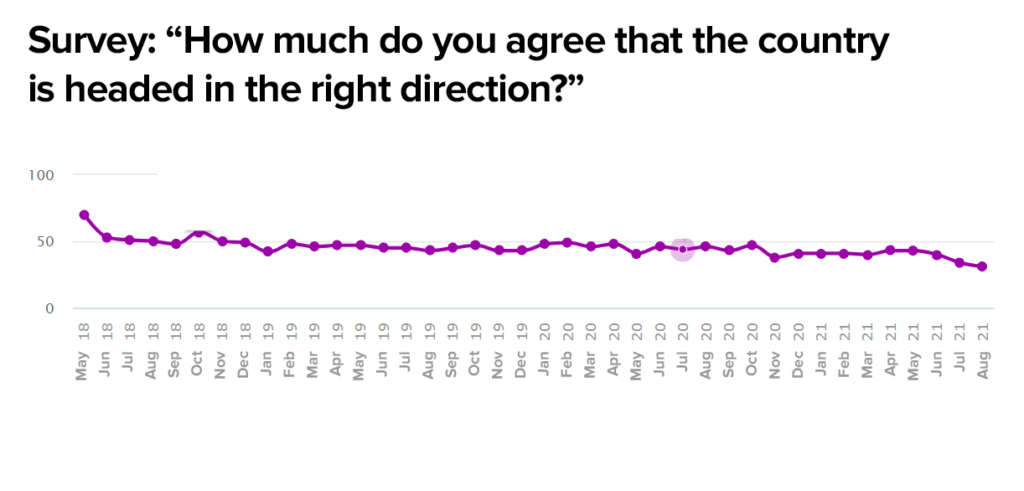

In May 2020, on sanitary and epidemiological grounds, the Russian Central Election Commission was granted permission to hold elections over the course of three days, rather than just one. This made the task of election monitoring significantly more complicated and created greater opportunities to create an environment conducive to pressure and direct fraud (the 2021 elections took place over three days, on September 17, 18, and 19). At the same time, the pandemic led to a deterioration in social and economic conditions, small and medium businesses failed in the face of restrictions, while frustration, depression, and a sense of hopelessness grew among Russia’s citizens, which unsurprisingly soured voters on the governing party and drove many to exercise a protest vote. Russia’s largest official polling agency VTsIOM publicly acknowledged the growth in social pessimism in the spring of 2020[1]:

The data above are from VTsIOM‑SPUTNIK surveys—VTsIOM’s daily nationwide telephone survey.

The 2021 elections are also notable because they took place in the wake of the 2020 constitutional reform, which granted the Russian President even more powers than before (especially when it comes to his influence on the judicial system), which greatly complicated the task of protecting citizens’ rights abroad (an attempt to shift from the priority of international law in human rights). The reform also introduced many new prohibitions on electoral rights into the Constitution, whereas they had previously only been contained in laws.

The combination plunging approval for the government and an updated Constitution that has opened the door to new opportunities for repression has led to an unprecedented level of government pressure on civil society and opposition organizations and politicians, even by Russian election standards. The pressure campaign was triggered by authorities’ nervousness and uncertainty over election results. Targeted pressure campaigns are nothing new in Russia, but this time, things were far more widespread, with victims numbering in the thousands. In 2021, a “victim” is not necessarily just a citizen deprived of his or her right to run for office, but also often someone who was actually arrested or forced to emigrate.

Against the backdrop of the pandemic and new restrictions, on May 23, 2020, law number 153‑FZ was adopted, depriving citizens who have been sentenced to imprisonment for medium‑gravity crimes (under Article 50 of the Russian Criminal Code) from being elected for a five‑year period after their criminal record has been dismissed or expunged. This has affected many people convicted of medium‑gravity crimes, including those that carry suspended sentence, whether they were sentenced for crimes against individuals or “political” crimes (such as “public dissemination of knowingly false information,” “repeated violations of regulations on organizing rallies,” “calls for separatism,” “extremism,” or “use of violence against representatives of the authorities”). Vast numbers of people have found themselves charged with white‑collar crimes such as fraud, misappropriation of funds, or embezzlement, in addition to drug offenses.

Following the arrest of Alexei Navalny on January 17, 2021 immediately upon his return to Russia and the protests that broke out in response, nearly all regional divisions of Navalny supporters’ organizations (the nonprofit FBK, or Anti‑Corruption Foundation, and the Navalny headquarters) were violently crushed—some Navalny allies fled the country, while others were arrested. On April 16, 2021, it was reported that the Moscow Prosecutor’s Office had filed a suit to recognize the FBK, Navalny headquarters, and the Foundation for the Protection of Citizens’ Rights (FZPG; another group associated with the FBK since 2019) recognized as extremist organizations. The Prosecutor’s Office stated that “the actual goals of their activities are to create the conditions for altering the foundations of the constitutional order, including by way of a ‘color revolution’ scenario”[2]. On June 9, 2021, the courts ordered them all liquidated. Following a protest in support of Alexei Navalny in January and February 2021 alone, 17,600 individuals were arrested in 125 cities[3]. Over 9,000 administrative charges were filed, and 90 criminal cases were opened. Nearly 1,800 individuals are still behind bars following the April 21 protest[4].

On May 27, 2021, it was reported that the Open Russia organization would be shuttering all of its activities and closing its branches in the regions. Executive director Andrei Pivovarov announced that the decision was made in order to protect supporters from criminal prosecution. “All members of [Open Russia] have been expelled from the organization and their membership has been canceled, in order to avoid any possible harassment. We do not need any new fines or criminal charges, and we want to protect our supporters,”[5] he stated. The police have linked Open Russia with the British organization Open Russia Civic Movement founded by Mikhail Khodorkovsky, an organization that the authorities had previously deemed “undesirable” and liquidated in 2019. Andrei Pivovarov himself was removed from a flight to Warsaw from St. Petersburg on the evening of May 31 and taken to Krasnodar, where he was arrested and charged with cooperating with an undesirable organization (Article 284.1 of the Russian Criminal Code).

At the same time the case against the FBK, Law 157‑FZ was hastily passed (the entire procedure took just a month from the time of filing, in violation of the Duma’s own laws and regulations) on June 4, 2021, denying Russian citizens of their right to be elected if they have been involved with a social, religious, or other organization that the court has ordered liquidated or shut down after recognizing that organization as extremist or terrorist in nature. Organization founders, managers, and the heads of regional or other divisions and their deputies who held one of these positions in the three years prior to the date on which the court ruling entered into force may not be elected for a five‑year period. “Ordinary” participants, members, or employees of that organization or other individuals involved in its activities beginning up to one year prior to the entry into force of the court ruling to liquidate the organization or ban its activities are deprived of their right to be elected for a three‑year period following the entry into force of that court ruling. The law specifies that any expressions of support via statements, including those made online or via other means (including donations or other assistance) may be considered as involvement with the organization. Contrary to common legal standards, this law has retroactive force, meaning that it punishes people for activities that, at the time they were committed, were not illegal. Vague wording (about statements of support online or providing any type of assistance) opens the door wide for any authorities seeking to use it arbitrarily against any opposition‑minded citizens.

It is impossible to calculate the exact number of Russian citizens who are now deprived of their right to be elected. According to rough estimates by the Golos association, no less than nine million Russian citizens, or about 8% of the total electorate, are currently prohibited from running for office (and the real number is likely far higher). Law 157‑FZ’s entry into force and the recognition of Navalny’s organizations as “extremist” means that hundreds of thousands more politically active citizens’ rights are also being trampled on[6].

Thus, the Russian government is attempting to quash and subdue citizens’ protest activities as much as possible. However, in no way does the fear of becoming a victim of repressions negate Russians’ growing dissatisfaction with their worsening quality of life and lack of opportunities for a dignified and secure future. Citizens are afraid, but so are candidates and political parties (especially the “systemic” parties represented in the State Duma). Therefore, they are very careful when expressing any criticism, always while observing many unwritten “limits,” and ritually distance themselves from Alexei Navalny and his supporters. Examples of this behavior are the CPRF leader Gennady Zyuganov and the founder of nominally liberal party Yabloko, Grigory Yavlinskiy.

Officially, the Kremlin managed to retain control over the electoral system, control voting in the regions largely viewed as its “electoral sultanates” (regions rife with electoral fraud), hold onto its constitutional majority in parliament, bring political parties loyal to the Kremlin into the Duma, and cut the non‑systemic opposition out of the electoral process altogether. Voter fraud also made it possible to weaken systemic opposition in the Duma, notably the CPRF.

We can view the latest elections as a success for Putin’s regime. The Kremlin has achieved the following goals:

- United Russia retained its constitutional majority in the Duma;

- No mass protests broke out following the election results;

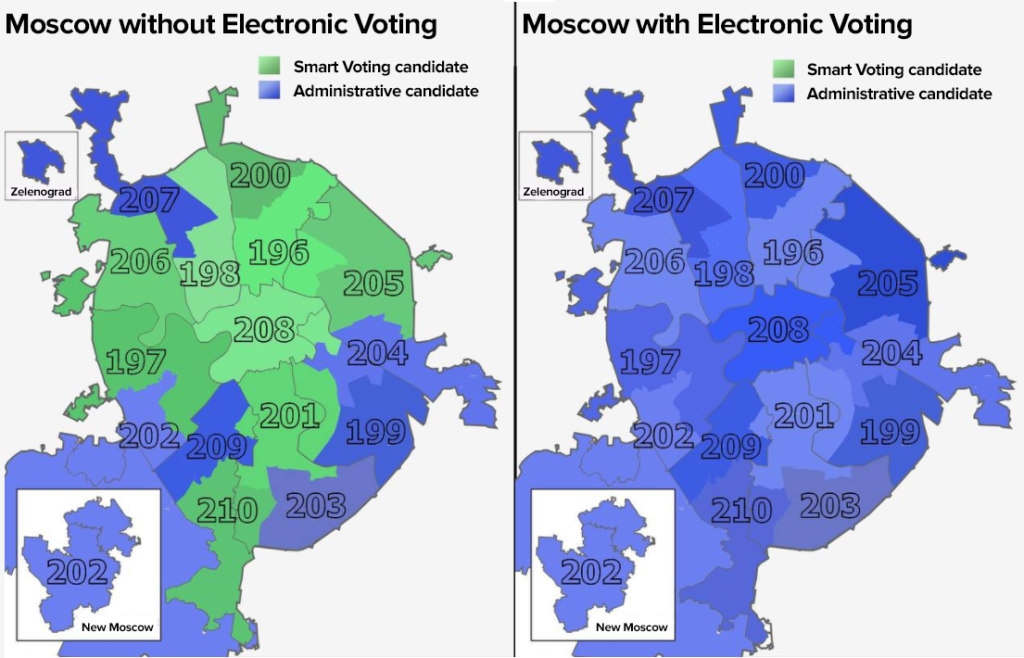

- The electronic voting system made it possible to falsify votes in Moscow (the region most prone to protesting the Kremlin);

- Smart Voting failed to win in a large number of constituencies, with disappointing results, even in Russia’s traditional protest regions;

- The authorities managed to supress the voter turnout, especially in major cities;

- For the first time in an election, media resources blocked both systemic (CPRF) and non‑systemic politicians (Alexei Navalny supporters), under direct pressure from the Kremlin. For the first time, international corporations like Google and Apple took part in blocking Smart Voting by blocking Smart Voting media resources just three days prior to the elections.

Nonetheless, not everything was quite so rosy for the authorities, who did see some setbacks during these elections.

- A big number of politicians, experts, and ordinary citizens are now challenging the reliability of electronic voting;

- Against the backdrop of plummeting real support for United Russia and lower voter turnout than in 2011, more votes had to be falsified compared to 2011 and 2016. Thus, there is some “environmental resistance” limiting just how many votes can be falsified;

- The potential for protest in the regions of the Far East, Siberia, and Northwest Russia (see table below) has not gone anywhere;

- The potential for voter fraud did not expand with the institution of a three‑day voting period (the authorities extended the voting period from one to three days, from September 17–19, 2021, citing measures to fight the pandemic). Initially, many members of the opposition feared that the change would increase opportunity for fraud, though in practice, the list of regions in Russia where votes were counted honestly or relatively honestly did not actually change much at all, nor did the total volume of fraud overall). The reason for their fears was that the new, three‑day voting period introduced a procedure in which ballots are stored for one or two days, during which time they can easily be replaced or destroyed. In practice, however, this was not widespread;

- Voting abroad was a complete disaster as far as the Kremlin was concerned—Smart Voting candidates won in nearly every embassy. The Kremlin’s saving grace was the fact that voting abroad represented only 0.38% of the votes cast;

- The Kremlin did not manage to obtain any clear recognition of the elections from the international community.

Assessing the elections from the opposition’s perspective is most logical when we divide the opposition into systemic (political parties and politicians registered for elections) and non‑systemic—in these elections, mostly supporters of Alexei Navalny, and more broadly, Smart Voting.

For the systemic opposition, these elections were a success:

- The CPRF, A Just Russia, and New People increased their number of seats in the Duma;

- Candidates from these parties were not subjected to any significant reprisals at the hands of the Kremlin;

- The CPRF actually strengthened its position as Russia’s main opposition party, including through an attempt at holding a public demonstration in Moscow against voter fraud;

- New People entered the Duma on its first election.

The following can be considered as failures:

- The LDPR led a very confusing campaign, losing nearly half of its seats in the Duma;

- Support for Yabloko has plummeted. Many strong Yabloko candidates were barred from running in the State Duma elections at all;

- The CPRF was unable to shield former presidential candidate Pavel Grudinin from being barred from running, and it was unable to collect enough funds for its electoral fund, nor was it able to register a number of strong regional supporters as candidates.

The non‑systemic opposition executed the Smart Voting strategy, which aimed to throw support behind constituencies’ second‑strongest candidate after United Russia. It is difficult to assess whether the campaign was successful or not, though it did achieve the following:

- Voting at Russian Embassies abroad went almost entirely according to Smart Voting recommendations (this comes as no surprise, as polling at the embassies was randomly assigned to majority districts, and as a result, voters at embassies were voting on candidates from regions on which they had almost no information, while Smart Voting made up for the lack of information on these options);

- In Moscow (in nine of 15 single‑mandate constituencies), the Smart Voting candidate won at nearly every polling station, and the authorities were forced to completely falsify electronic voting data in order to ensure the victory of candidates with the Kremlin’s stamp of approval;

- A similar situation played out in six of eight districts in St. Petersburg;

- 15 Smart Voting candidates were sent to the Duma, with 169 more in second place. That is more mandates than the New People party, which took just 13 seats.

One downside of Smart Voting was that many voters preferred not to vote for the candidate recommended by Smart Voting, but for other parties or candidates altogether.

For example, in Irkutsk Oblast (considered by experts from the Golos voter rights movement to be a region with an honest vote count), in all four constituencies, Smart Voting recommended voting for candidates from the CPRF. However, study of the voting results shows that while United Russia candidates lost votes in all four constituencies, the additional votes did not go to the CPRF, but to candidates from other parties. New People obtained 9.99% of the vote in Irkutsk Oblast, meaning that people preferred the strategy of voting for the candidate of their choice. In fact, Smart Voting recommendations had the greatest effect in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and the embassies. In the other territories, it is difficult to determine where Smart Voting worked, and where voters simply voted for their preferred candidate. We can also consider the “bet on YouTube” strategy employed by the non‑systemic opposition a failure. The fact that major global corporations blocked Smart Voting websites highlights the inherent vulnerabilities of using this method to share information.

Russia’s September 19 State Duma Elections cannot be considered free nor fair.

Below are some of the main criticisms of the campaign:

As noted above, according to official data, United Russia won the State Duma elections held on September 17–19, 2021, taking 49.82% of the votes, giving it 126 out of 225 spots on the party lists. In the majority part of the State Duma, it won 198 out of 225 seats (the Duma operates with a relative majority or first‑past-the‑post system). As a result of this total victory in the majority, United Russia’s total number of seats is now 324, a constitutional majority. Nonetheless, it lost seats compared to 2016, when it won 54.2% of the vote from the party lists, and a total of 343 seats. Throughout the campaign, United Russia’s approval rating remained low, and even according to official polling service VTsIOM, fluctuated around 27–28%[7].

That discrepancy is possible due to differences in the political and electoral‑geographical situation in the Russian regions, which exhibit extremely strong variations in electoral behavior. There is one group of regions with its core in several national regions of the North Caucasus and Volga region with rigid, authoritarian political rule, where the authorities always announce incredibly high turnout (often 80–90%) and equally high percentages of votes for the ruling party. According to independent electoral experts and the opposition alike, in reality, turnout in these regions is not much different from that of other areas of the country, and voter fraud is rampant.

Several other regions that saw widespread electoral deviations (Kuzbass, Yamalo‑Nenets Okrug, and others) are also added to this group. Experts refer to these regions as “electoral anomalies” or “electoral sultanates”. They have always shown high results for Russia’s ruling party, and those figures only grew in the 2000s as turnout dropped in more politically competitive areas.

Since 2016, State Duma elections were moved from December to September, which, as in previous regional elections, created additional problems with the mobilization of independent voters. As a result, the September 18, 2016 State Duma elections saw the highest differentiation among the Russian regions in voter turnout since the fall of the Soviet Union.

Voter turnout by region

| Region | Took part in elections (turnout) | ||

| 2011 | 2016 | 2021 | |

| Republic of Adygea | 65.9% | 53.9% | 68.21% |

| Altai Republic | 63.6% | 45.1% | 46.19% |

| Republic of Bashkortostan | 79.3% | 69.8% | 72.79% |

| Republic of Buryatia | 56.9% | 40.5% | 44.97% |

| Republic of Dagestan | 91.1% | 88.1% | 84.52% |

| Republic of Ingushetia | 86.4% | 81.4% | 83.68% |

| Kabardino‑Balkar Republic | 98.4% | 90.1% | 85.78% |

| Republic of Kalmykia | 63.2% | 57.5% | 50.12% |

| Karachay‑Cherkessia Republic | 93.2% | 93.3% | 89.36% |

| Republic of Karelia | 50.3% | 39.6% | 37.64% |

| Komi Republic | 72.6% | 40.8% | 39.47% |

| Republic of Crimea | — | 49.1% | 49.75% |

| Mari El Republic | 71.3% | 53.4% | 46.11% |

| Republic of Mordovia | 94.2% | 83.0% | 65.11% |

| Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) | 60,1% | 48.1% | 50.24% |

| Republic of North Ossetia- Alania | 85.8% | 85.6% | 86.61% |

| Republic of Tatarstan | 79.5% | 78.8% | 78.92% |

| Tuva Republic | 86.1% | 90.1% | 83.28% |

| Udmurt Republic | 56.6% | 44.5% | 47.45% |

| Republic of Khakassia | 56.2% | 39.4% | 37.54% |

| Chechen Republic | 99.5% | 94.9% | 94.42% |

| Chuvash Republic | 61.7% | 59.4% | 57.14% |

| Altai Krai | 52.5% | 40.8% | 40.95% |

| Zabaykalsky Krai | 53.6% | 38.9% | 39.35% |

| Kamchatka Krai | 53.6% | 39.5% | 42.37% |

| Krasnodar Krai | 72.6% | 51.2% | 65.41% |

| Krasnoyarsk Krai | 49.7% | 36.7% | 42.15% |

| Perm Krai | 48.1% | 35.2% | 39.01% |

| Primorsky Krai | 48.7% | 37.4% | 42.58% |

| Stavropol Krai | 50.9% | 42.1% | 67.11% |

| Khabarovsk Krai | 53.2% | 36.9% | 44.31% |

| Amur Oblast | 54.0% | 42.5% | 41.65% |

| Arkhangelsk Oblast | 50.0% | 36.6% | 41.58% |

| Astrakhan Oblast | 56.0% | 37.0% | 46% |

| Belgorod Oblast | 75.5% | 62.2% | 59.07% |

| Bryansk Oblast | 59.9% | 55.1% | 68.65% |

| Vladimir Oblast | 48.9% | 38.4% | 37.89% |

| Volgograd Oblast | 52.0% | 42.2% | 64.97% |

| Vologda Oblast | 56.3% | 40.9% | 45.53% |

| Voronezh Oblast | 64.3% | 53.8% | 53.86% |

| Ivanovo Oblast | 53.2% | 38.5% | 38.26% |

| Irkutsk Oblast | 47.1% | 34.7% | 36.99% |

| Kaliningrad Oblast | 54.6% | 44.1% | 46.15% |

| Kaluga Oblast | 57.6% | 43.1% | 44.18% |

| Kemerovo Oblast | 69.4% | 86.8% | 73.48% |

| Kirov Oblast | 54.0% | 41.9% | 45.04% |

| Kostroma Oblast | 57.3% | 39.4% | 39.54% |

| Kurgan Oblast | 56.5% | 41.8% | 48.28% |

| Kursk Oblast | 54.7% | 47.0% | 47.01% |

| Leningrad Oblast | 51.5% | 44.1% | 44.27% |

| Lipetsk Oblast | 56.9% | 52.6% | 52.72% |

| Magadan Oblast | 52.6% | 40.6% | 43.7% |

| Moscow Oblast | 51.0% | 38.2% | 45.35% |

| Murmansk Oblast | 51.9% | 39.7% | 43.84% |

| Nizhny Novgorod Oblast | 58.9% | 44.5% | 48.47% |

| Novgorod Oblast | 56.6% | 39.9% | 41.12% |

| Novosibirsk Oblast | 56.8% | 34.9% | 37.73% |

| Omsk Oblast | 55.7% | 38.7% | 41.38% |

| Orenburg Oblast | 51.2% | 41.7% | 45.86% |

| Orel Oblast | 64.7% | 53.6% | 49.99% |

| Penza Oblast | 64.9% | 60.6% | 57.52% |

| Pskov Oblast | 52.9% | 42.1% | 44.81% |

| Rostov Oblast | 59.3% | 48.2% | 48.8% |

| Ryazan Oblast | 52.7% | 43.3% | 48.03% |

| Samara Oblast | 53.0% | 52.9% | 46.77% |

| Saratov Oblast | 67.3% | 64.5% | 55.71% |

| Sakhalin Oblast | 49.1% | 37.1% | 39.94% |

| Sverdlovsk Oblast | 51.2% | 41.5% | 48.47% |

| Smolensk Oblast | 49.6% | 40.4% | 41.87% |

| Tambov Oblast | 68.3% | 49.3% | 58.87% |

| Tver Oblast | 53.5% | 41.6% | 42.46% |

| Tomsk Oblast | 50.5% | 33.9% | 41.47% |

| Tula Oblast | 72.8% | 45.6% | 53.17% |

| Tyumen Oblast | 76.2% | 81.1% | 61.54% |

| Ulyanovsk Oblast | 60.4% | 52.4% | 45.88% |

| Chelyabinsk Oblast | 59.7% | 44.4% | 46.54% |

| Yaroslavl Oblast | 55.9% | 37.8% | 43.4% |

| Moscow | 61.7% | 35.3% | 50.12% |

| St. Petersburg | 55.2% | 32.7% | 37.61% |

| Sevastopol | — | 47.0% | 49.27% |

| Jewish Autonomous Oblast | 52.1% | 39.6% | 63.13% |

| Nenets Autonomous Okrug | 56.1% | 44.8% | 42.61% |

| Khanty‑Mansi Autonomous Okrug | 54.9% | 39.3% | 46.62% |

| Chukotka Autonomous Okrug | 79.1% | 64.5% | 61.29% |

| Yamalo‑Nenets Autonomous Okrug | 82.2% | 74.4% | 67.41% |

| Russian Federation | 60.2% | 47.9% | 51.72% |

In Russia, there is no unified scale for defining the list of so‑called “anomalous” regions (areas of widespread, systematic voter fraud, known as “electoral sultanates” by Dmitry Oreshkin).

Here, we can distinguish two approaches. Electoral statistics researcher Sergey Shpilkin used a mathematical modeling system for analysis (distribution graphs by voter turnout at polling places and the number of voters at specific polling stations) in 2011 and then 2016 to divide all of the regions (with the exception of Chukotka Autonomous Region, due to insufficient data) by voting distribution curves and the share of “anomalous” voting into several groups. The first group (which he refers to as “totally fabricated”) includes 15 regions, where there were practically no clusters of polling stations with low turnout and results for United Russia. It includes the Republics of Bashkortostan, Dagestan, Ingushetia, Mordovia, North Ossetia- Alania, Tatarstan, Tuva, Kabardino‑Balkaria, Karachay‑Cherkessia, Chechnya, and Bryansk, Kemerovo, Saratov, Tyumen Oblasts, and Yamalo‑Nenets Autonomous Okrug. According to Shpilkin, the total share of “anomalous votes” in these regions was 7.5 million.

The second group (which Shpilkin refers to as “falsified”) was made up of nine regions, in which the share of “anomalous” votes exceeded 10% of the registered number of voters. It includes the Republics of Adygea, Kalmykia, Chuvashia, Belgorod, Voronezh, Lipetsk, Penza, Rostov, and Tambov Oblasts. The total share of “anomalous” votes in these regions numbers over 1.6 million.

Shpilkin classified the remaining regions (60) as “relatively clean” and “clean,” with 3% of the registered voters as the dividing line between the two groups (of which there are equal numbers). It is worth noting that Shpilkin’s method is effective for detecting anomalies associated with higher voter turnout (“stuffing the ballot box,” organized votes under pressure, and other forms of manipulation). The same methods may not detect manipulation associated with “transferring” votes from one party to another.

The second approach was described in the book How Russia Voted in 2016 by Alexandr Kynev and Arkady Lyubarev for the Civil Initiatives Committee (CIC) [Комитет гражданских инициатив], and divides regions into three groups based on voter turnout. The first group includes regions with a turnout below 54%, and includes most regions (65). The second, intermediate group includes regions with a turnout of 55% to 65% (regions with increased turnout), and includes seven regions (Kalmykia, Chuvashia, Belgorod, Bryansk, Penza, Saratov Oblasts, and Chukotka Autonomous Okrug). The third group, with turnout above 69% (regions with very high turnout) includes 13 regions—the Republics of Bashkortostan, Dagestan, Ingushetia, Kabardino‑Balkaria, Karachay‑Cherkessia, Mordovia, north Ossetia, Tatarstan, Tuva, Chechnya, Kemerovo, and Tyumen Oblasts, as well as Yamalo‑Nenets Autonomous Okrug.

That division for the CIC was similar to Sergei Shpilkin’s classification based on distribution curves. Shpilkin included all 13 regions with very high turnout in the first group, as well as Bryansk and Saratov Oblasts, which were included in the group with increased turnout by the CIC book. Shpilkin included four regions with increased turnout and five regions with turnout below 54% in the second group.

It is also noticeable that regions with high voter turnout also demonstrated strong support for United Russia. Average turnout in the first group is 41.7%, and an average of 46.7% of these voters voted for United Russia. In the second group, turnout is 61.0%, and support for United Russia stands at 61.9%. In the third group, the average turnout is 81.3%, with 75.9% of voters supporting United Russia. Regions in the third group, which makes up just 12.8% of Russia’s voters, represented 21.8% of the votes overall and 30.6% of the votes for United Russia.

It is also important to note that the electoral situation in the regions is fluid. There are some regions that have been part of the “anomalous” category for 20 years, but there are others that have been part of and then left this group. For example, under Governor Nikolay Kolesov from Tatarstan in 2007–2008, Amur Oblast’s indicators were anomalous, before then returning to normal distribution following Kolesov’s ouster. Under Vyacheslav Gayzer, the Komi Republic became anomalous, though it returned to the category of protest and “electorally normal” regions following the arrest of Gayzer and several other high‑level leaders in Komi (including the former chair of the Komi Republic Electoral Commission, Yelena Shabarshina). Under Governor Vladimir Gruzdev, Tula Oblast also joined the group of anomalous regions.

Many regions have their own internal anomalous zones (for example, Ussuriisk in Primorsk and Primorsky Krais, or Oleninsky Municipal District (now municipal okrug) in Tver Oblast, etc.).

However, it appears incorrect to classify regions as anomalous solely based on high turnouts (a turnout of 57–60% is above the national average, though it cannot be considered anomalous). For example, historically, the rural areas of Chuvashia and Belgorod Oblasts have always shown high turnout, though in the region as a whole, that does not go hand in hand with an abnormal percentage of votes for one party. Therefore, we cannot consider Chuvashia as an abnormal region (only 50.9% voted for United Russia in 2016), as is the case in Belgorod (54.7% in 2016). At the same time, in 2016, United Russia results were anomalous in Krasnodar Krai (59.3%), Voronezh Oblast (58.7% with a turnout of 53.8%), Rostov Oblast (58.8%), and Tyumen Oblast (58.4%).

Thus, 58–60% support for United Russia can be considered the “cutoff threshold” for anomalous and semi‑anomalous regions in 2016. The Nizhny Novgorod Oblast indicators are close to these figures (58.2% in 2016, with obvious fraud in three districts of Nizhny Novgorod), despite the fact that there is no large‑scale falsification of voter turnout numbers (turnout was just 44.5% in 2016).

As a result, 24 regions can be classified as “anomalous” or “semi‑anomalous”, given the extremely high official turnout figures and similarly high percentages of votes for one party in 2016. These regions are home to about 30 million voters, or 27.4% of Russia’s registered voters, though given the high turnout numbers, in 2016, they made up 38.04% of all ballots cast, and 49.3% of all votes for United Russia. As a rule, there is simply no way to increase turnout in these regions. Accordingly, any increase in turnout in the protest regions or areas that are simply strongly independent (large cities, most regions of the Urals, Siberia, the Far East, and the Russian North) should reduce the share of “anomalous” regions in the overall results, and with it, the number of votes for United Russia. In fact, the way everything played out during the 2021 campaign was related to one thing—the authorities’ desire to demoralize and discourage protest voters, inspiring a feeling that voting was a hopeless endeavor, and minimizing turnout as much as possible in protest regions. Though turnout in protest regions did slightly increase (total turnout grew from 47.88% to 51.72% in Russia), at the same time, United Russia’s final victory in 2021 hinged on voter fraud in “electoral sultanates”. The 2016 campaign was very quiet, without any major events (then, United Russia enjoyed a rather high approval rating, and the authorities reduced voter turnout in protest regions simply by holding a very boring, uneventful campaign).

Anomalous and semi‑anomalous regions during the 2016 elections

| Registered voters at the time of polls closing | Took part in elections (turnout) | Votes for United Russia | |

| Adygea | 339,685 | 183,133 | 108,778 |

| Bashkortostan | 3,040,845 | 2,121,993 | 1,195,246 |

| Dagestan | 1,653,807 | 1,457,044 | 1,294,629 |

| Ingushetia | 219,176 | 178,084 | 129,222 |

| Kabardino‑Balkar Republic | 536,867 | 483,776 | 375,942 |

| Kalmykia | 211,637 | 121,706 | 85,923 |

| Karachay‑Cherkessia Republic | 306,375 | 285,859 | 233,498 |

| Crimea | 1,493,965 | 734,230 | 534,362 |

| Mordovia | 628,822 | 522,021 | 440,108 |

| North Ossetia | 528,993 | 453,029 | 303,794 |

| Tatarstan | 2,886,295 | 2,273,070 | 1,939,563 |

| Tuva | 156,983 | 141,482 | 116,372 |

| Chechnya | 695,573 | 660,249 | 635,729 |

| Krasnodar Krai | 3,989,178 | 2,041,529 | 1,208,327 |

| Bryansk Oblast | 1,015,760 | 560,169 | 357,780 |

| Voronezh Oblast | 1,873,592 | 999,509 | 586,142 |

| Kemerovo Oblast | 2,032,985 | 1,764,703 | 1,363,181 |

| Penza Oblast | 1,097,837 | 665,571 | 427,283 |

| Rostov Oblast | 3,256,186 | 1,567,627 | 921,087 |

| Saratov Oblast | 1,940,501 | 1,249,759 | 850,392 |

| Tambov Oblast | 856,499 | 421,964 | 267,730 |

| Tyumen Oblast | 1,080,797 | 876,921 | 511,529 |

| Chukotka Oblast | 29,725 | 19,170 | 11,266 |

| Yamalo‑Nenets Autonomous Oblast | 355,145 | 264,144 | 177,214 |

| TOTAL | 30,227,228 | 20,046,742 | 14,075,097 |

| Share of Russian Federation | 27.46% | 38.04% | 49.34% |

| Russian Federation | 110,061,200 | 52,700,992 | 28,527,828 |

It is clear that for 2021, the following regions should be excluded from the so‑called “anomalous zones”: Kalmykia (widespread protest voting in a context of conflict between regional head Batu Khasikov and local elites, with a drop in turnout from 57% to 50%), Crimea (turnout was lower than the national average at 49.75%, with a drop in votes for United Russia from 72.8% to 63.33%), Chukotka Autonomous Oblast (a drop in support for United Russia, to 46.7%, which cannot be considered an anomalous result, and Rostov Oblast (even taking into account electronic voting from Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic, turnout was only 48.8%, below the national average), and Voronezh Oblast (turnout remained at 53.8%, which is only higher than the national average for 2021).

It is also clear that in 2021, Stavropol Krai once again joined the category of anomalous zones (there was an abnormal spike in turnout, from 42% to 67%), as did Volgograd Oblast (turnout grew from 42% to 65%), and for the first time, the Jewish Autonomous Oblast (turnout grew from 39.6% to 63%, alongside an increase in votes for United Russia, from 45% to 56%).

In all, 22 regions make up the list of most anomalous regions for 2021. Though they are home to 25.12% of Russia’s registered voters (26.4 million), they represent 34.3% of the votes cast, and 47% of the votes for United Russia.

If we add Crimea and Voronezh Oblast to this list, that share grows to 28.18%, 37.33%, and 50.70%, respectively. Thus, the overall share of anomalous and semi‑anomalous regions, the number of voters, and number of votes for United Russia has remained more or less stable.

Anomalous and semi‑anomalous regions in the 2016 elections

| Registered voters at the time of polls closing | Took part in elections (turnout) | Votes for United Russia | |

| Adygea | 341,943 | 233,246 | 154,491 |

| Bashkortostan | 3,008,258 | 2,189,823 | 1,458,777 |

| Dagestan | 1,699,609 | 1,436,544 | 1,164,969 |

| Ingushetia | 234,660 | 196,372 | 167,239 |

| Kabardino‑Balkar Republic | 539,787 | 463,053 | 366,099 |

| Karachay‑Cherkessia Republic | 301,151 | 269,109 | 215,309 |

| Mordovia | 590,906 | 384,760 | 253,523 |

| North Ossetia | 520,743 | 451,010 | 320,410 |

| Tatarstan | 2,941,538 | 2,321,427 | 1,833,035 |

| Tuva | 197,564 | 164,526 | 140,090 |

| Chechnya | 775,256 | 731,968 | 703,613 |

| Krasnodar Krai | 4,320,254 | 2,826,045 | 1,720,921 |

| Stavropol Krai | 1,889,696 | 1,268,308 | 783,327 |

| Bryansk Oblast | 964,117 | 661,820 | 425,333 |

| Volgograd Oblast | 1,807,406 | 1,174,357 | 685,705 |

| Kemerovo Oblast | 1,939,447 | 1,425,122 | 1,003,578 |

| Penza Oblast | 1,036,556 | 596,244 | 335,032 |

| Saratov Oblast | 1,865,540 | 1,039,249 | 618,244 |

| Tambov Oblast | 817,686 | 481,413 | 273,771 |

| Tyumen Oblast | 1,136,676 | 699,502 | 358,631 |

| Jewish Autonomous Oblast | 125,347 | 79,135 | 44,623 |

| Yamalo‑Nenets Autonomous Oblast | 376,862 | 254,054 | 174,561 |

| Total | 27,431,002 | 1,934,7087 | 13,201,281 |

| Share of Russian Federation | 25.12% | 34.26% | 47.04% |

| Russian Federation | 109,204,662 | 56,484,685 | 28.064,200 |

If we use Sergey Shpilkin’s calculations, the distribution of votes for parties by turnout, according to the proportional system and distribution of polling stations in coordinates, the turnout for 2021’s elections is rather ordinary for Russian elections, and in general does not greatly differ from the distributions seen in, say 2011 and 2016. Moreover, the distribution of the “main core” of polling stations by turnout (about 38%) coincides with that of 2016, and by votes for United Russia (about 32%), coincides with that of 2011. Shpilkin’s calculation gives (based on available, incomplete data) about 13.7 million fraudulent votes for United Russia. Subtracting these presumably “enhanced” votes gives us a corrected result of 33% for United Russia, which is well in line with the “cometary nucleus” in Shpilkin’s graphs (31%). In a beautiful coincidence, the number of real votes for United Russia is the same (based on available data, about 13.7 million, and roughly 14 million adjusted for unaccounted polling stations). According to Shpilkin, this is the lowest level of real support on a proportional system that United Russia has ever seen. The share of questionable votes making up United Russia’s results—50%—is also a record (in 2011, this figure was about 45%, and in 2016, about 43%). By Shpilkin’s estimates, without this factor, United Russia would have received about 33% of the votes, rather than 50%, with the CPRF receiving 25% rather than 19%, and LDPR and A Just Russia—For Truth receiving 10% rather than 7.5%, and New People receiving 7% rather than just over 5%. Other parties would not have had any hope of reaching the 5% threshold[8].

In addition to the “electoral sultanates,” an experiment in online voting (Remote Electronic Voting, REV) also boosted turnout and fraud in favor of United Russia. A special law was adopted for REV, and the Central Election Commission established a list of seven regions participating in the experiment—Moscow, Sevastopol, Kursk, Murmansk, Nizhny Novgorod, Rostov, and Yaroslavl Oblasts. In order to take part in REV, voters needed to submit an electronic application between August 2 and September 13. It is impossible to establish who voted via REV and how they voted, as well as whether the official results correspond to the real ones, according to the opposition.

Officially, citizens chose to take part in REV by submitting an application via an electronic public service system. However, there have been multiple reports of the employees of government agency employees and various corporations being coerced into taking part in REV. There was a raffle for online voting participants in Moscow, who stood to win prizes, including a one‑bedroom apartment in Moscow, cars, and even 10,000; 25,000; 50,000, and 100,000 prize points, which can be spent on charity, purchases at cafes and restaurants, buying goods, furniture, groceries, and medicine. The first drawing took place on September 18, and winners were chosen by a random number generator. The last prize drawing among Moscow’s electronic voters was held on September 20, from 9:00 to 10:00 am live on the Moskva 24 television station.

When citizens registered with the REV system, they were excluded from the voter lists at polling stations and voted using their registration data on the portal at vybory.gov.ru. This experiment was carried out in Sevastopol, Kursk, Nizhny Novgorod, Murmansk, Rostov, and Yaroslavl Oblasts (Moscow voted on its own platform at https://elec.mos.ru/). In the case of Rostov Oblast, residents of unrecognized Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic who were granted Russian citizenship through a streamlined process were able to complete a simplified voter registration, through an email address alone, rather than through a mobile phone number registered in the Russian Federation. Additionally, there were other differences in Moscow’s REV, for example, the option for deferred voting, through which voters had 24 hours to change their selection (the last vote was counted). Moscow’s leaders explained that this option was introduced to avoid voting under duress, for example, if someone voted for the first time under pressure from their employer, they would be able to later change their vote from home.

In relative terms, Russia’s voter turnout increased from 47.9% to 51.72% between 2016 and 2021, and from 52,700,992 to 56,484,685 (or by 3,683,693) in real terms. A total of 2,530,839 voters voted via REV, which represents 67% of the growth in turnout. REV’s contribution is clearly proven by Moscow, which represented 76.8% of REV voters, and where turnout jumped from 35.3% in 2016 to 50.12% in 2021. REV led to the fact that before REV results were introduced to the State Automated System “Vybory”, opposition candidates were ahead in nine Moscow districts, only for all 15 candidates supported by Moscow Mayor Sergey Sobyanin to win after REV results were introduced. At the same time, REV results in Moscow were only published 12 hours after the polls had closed, once the authorities knew exactly how many “missing” votes their preferred candidates would need in order to ensure a win. The REV system, which was nearly devoid of any public monitoring, drew harsh criticism, and members of the opposition and the general public claimed that it permitted electoral fraud.

On September 23, members of the Moscow precincts and territorial election commissions, along with election observers, called for a cancellation of Moscow’s REV results. They sent an open letter to Alexei Venediktov, the head of the Moscow public headquarters for election observation, stating that the electronic voting system “is a tool for fraud,” and listing reasons why REV should not be accepted. These reasons included:

– Repeatedly, voters arrived at polling stations, only to be surprised to learn that they were registered for REV, though they had never registered themselves;

– There were technical failures that resulted in interruptions to even the scanty levels of REV observation that were provided;

– Approximately 300,000 voters changed their votes in REV[9].

REV results by region

| Kursk Oblast | Murmansk Oblast | Nizhny Novgorod Oblast | Rostov Oblast (no exact data on voting from DPR/LPR) | Yaroslavl Oblast | Moscow | Sevastopol | |

| Total regional turnout | 424,788 (47%) | 257,491 (43.83%) | 1,246,472 (48.47%) | 1,659,674 (48.8%) | 436,834 (43.4%) | 3,903,133 (50.12%) | 166,555 (49.27%) |

| Regional turnout without REV | 377,834 (41.8%) | 211,496 (36%) | 1,130,397 (44%) | 1,381,816 (40.63%) | 355,088 (35.28%) | 1,959,543 (25.16%) | 147,934 (43.46%) |

| REV | 46,954 | 45,995 | 116,075 | 277,858 | 81.746 | 1,943,590 | 18,621 |

| United Russia REV | 162,522 (43%) | 73,177 (34.6%) | 570,812 (50.5%) | 668,699 (48.4%) | 97,407 (27.43%) | 573,823 (29.3%) | 83,256 (56.3%) |

| United Russia with REV | 21,843 (46.52%) | 18,789 (40.85%) | 50,003 (43.08%) | 186,052 (66.96%) | 31,855 (38.97%) | 847,592 (43.6%) | 10,016 (53.79%) |

With regard to key changes in Russia’s electoral geography, for the first time since the 2000s, United Russia lost in four regions, and ended up in second place (Yakutia, Khabarovsk Krai, Nenets Autonomous Oblast, and Mari El). In 12 more regions, the CPRF took second place after United Russia, by a small margin (Altai Republic, Komi, Khakassia, Altai Krai, Primorsky Krai, Amur Oblast, Ivanovo Oblast, Irkutsk Oblast, Kostroma Oblast, Sakhalin Oblast, Ulyanovsk Oblast, Yaroslavl Oblast). It is clear that these regions are dominated by Siberia, the Far East, and North, where the CPRF has decisively supplanted the LDPR as the “number two” party.

United Russia’s worst results were in Khabarovsk Krai (24.51%), Nenets Autonomous Oblast (29.06%), Komi Republic (29.44%), Kirov Oblast (29.54%), and Yaroslavl Oblast (29.72%). In all five regions, its result was below 30%.

In 37 regions, United Russia received between 30–40% (the Altay Republic, Kalmykia, Mari El, Yakutia, Udmurtia, Khakassia, Chuvashia; the Altay Krai, Zabaikalsky Krai, Kamchatsky Krai, Krasnoyarsk Krai, Permsky Krai, Primorsky Krai; Amurskaya, Arkhangelsk, Vladimir, Vologod, Ivanovskaya, Irkutsk, Kaluzhskaya, Kostromskaya, Kurganskaya, Murmansk, Novgorod, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Orenburg, Orlovskaya, Sakhalinskaya, Sverdlovskaya, Smolenskaya, Tverskaya, Tomskaya, Ulyanovskaya, Chelyabinskaya Oblasts; Moscow and St. Petersburg). This is the largest group of regions— almost half the country.

United Russia’s best results were in Chechnya (96.13%), Tuva (85.34%), Dagestan (81.2%), Karachay‑Cherkessia (80.06%), Kabardino‑Balkaria (79.2%), Tatarstan (78.7%), North Ossetia (71.12%), Kemerovo Oblast (70.75%), Yamalo‑Nenets Autonomous Oblast (68.92%), Bashkortostan (66.7%), Adygea (66.45%), Mordovia (66%), Bryansk Oblast (64.32%), Crimea (63.33%), Stavropol Krai (61.83%) and Krasnodar Krai (60.98%). Thus, in 16 regions, it received over 60% of the votes. In 13 more regions, it received from 50% to 60% (Krasnodar Krai, Belgorod, Volgograd, Voronezh, Magadan, Penza, Rostov, Saratov, Tambov, Tula, Tyumen Oblast, Sevastopol, Jewish Autonomous Oblast). In 14 regions, United Russia received from 40% to 50%.

| Region | United Russia | CPRF | A Just Russia | LDPR | New People |

| Adygea Republic | 66.45% | 14.57% | 3.94% | 6.54% | 2.78% |

| Altai Republic | 38.5% | 30.09% | 8.85% | 7.85% | 4.92% |

| Bashkortostan Republic | 66.7% | 14.74% | 2.62% | 8.67% | 2.79% |

| Republic of Buryatia | 42.63% | 26.75% | 3.56% | 5.74% | 11.22% |

| Republic of Dagestan | 81.2% | 6.2% | 5.56% | 2.49% | 0.79% |

| Republic of Ingushetia | 85.18% | 3.65% | 5.13% | 1.77% | 0.6% |

| Kabardino‑Balkaria Republic | 79.2% | 16.69% | 2.9% | 0.35% | 0.07% |

| Kalmykia Republic | 39.52% | 25.97% | 5.86% | 3.44% | 12.23% |

| Karachay‑Cherkessia Republic | 80.06% | 13.02% | 2.01% | 1.88% | 0.33% |

| Republic of Karelia | 31.69% | 16.01% | 11.73% | 9.77% | 7% |

| Komi Republic | 29.44% | 26.88% | 8.33% | 11.96% | 9.57% |

| Republic of Crimea | 63.33% | 9.15% | 5.93% | 7.75% | 3.96% |

| Mari El Republic | 33.43% | 36.3% | 6.48% | 7.94% | 6.15% |

| Mordovia Republic | 66% | 12.99% | 4.3% | 7.75% | 2.99% |

| Sakha Republic (Yakutia) | 33.22% | 35.15% | 8.19% | 5.14% | 9.87% |

| Republic of North Ossetia—Alania | 71.12% | 11.49% | 10.54% | 1.43% | 0.56% |

| Republic of Tatarstan | 78.71% | 9.6% | 2.68% | 2.8% | 1.01% |

| Republic of Tuva | 85.34% | 4.2% | 2.99% | 1.82% | 2.28% |

| Udmurt Republic | 35.63% | 25.31% | 9.19% | 9.64% | 7.37% |

| Republic of Khakassia | 33.36% | 29.85% | 6.58% | 8.02% | 9.85% |

| Republic of Chechnya | 96.13% | 0.75% | 0.93% | 0.11% | 0.24% |

| Republic of Chuvashia | 37.18% | 22.51% | 14.91% | 6.78% | 5.71% |

| Altai Krai | 33.67% | 30.54% | 9.85% | 9.09% | 6.09% |

| Zabaykalsky Krai | 38.66% | 19.99% | 8.34% | 12.15% | 9.36% |

| Kamchatka Krai | 34.76% | 23.87% | 6.92% | 11.66% | 8.75% |

| Krasnodar Krai | 60.98% | 15.5% | 6.34% | 5.6% | 4.67% |

| Krasnoyarsk Krai | 34.64% | 22.87% | 6.14% | 13.68% | 7.84% |

| Perm Krai | 33.69% | 22.75% | 10.8% | 9.85% | 8.64% |

| Primorsky Krai | 37.42% | 28.24% | 6.19% | 7.71% | 5.59% |

| Stavropol Krai | 61.83% | 14.92% | 9.3% | 4.79% | 2.63% |

| Khabarovsk Krai | 24.51% | 26.51% | 6.46% | 16.18% | 7.72% |

| Amur Oblast | 34.32% | 26.51% | 5.54% | 14.17% | 7.04% |

| Arkhangelsk Oblast | 32.21% | 18.7% | 11.17% | 12.92% | 9.68% |

| Astrakhan Oblast | 48.1% | 17.84% | 12.2% | 5.34% | 5.68% |

| Belgorod Oblast | 51.65% | 18.67% | 6.88% | 7.23% | 5.51% |

| Bryansk Oblast | 64.32% | 13.7% | 4.97% | 8.6% | 2.33% |

| Vladimir Oblast | 37.64% | 25.95% | 7.78% | 9.42% | 7.31% |

| Volgograd Oblast | 58.43% | 14.77% | 5.77% | 11.12% | 3.01% |

| Vologda Oblast | 34.31% | 21.7% | 10.34% | 12.46% | 7.55% |

| Voronezh Oblast | 55.9% | 19.51% | 5.21% | 6.06% | 5.07% |

| Ivanovo Oblast | 36.24% | 28.02% | 7.63% | 9.38% | 5.9% |

| Irkutsk Oblast | 35.53% | 27.81% | 6.67% | 8.58% | 9.81% |

| Kaliningrad Oblast | 40.99% | 20.18% | 8.96% | 9.59% | 6.17% |

| Kaluzhskaya Oblast | 36.33% | 22.03% | 10.81% | 9.44% | 8.18% |

| Kemerovo Oblast | 70.75% | 9.35% | 5.69% | 6.24% | 1.85% |

| Kirov Oblast | 29.54% | 18.27% | 18.44% | 12.8% | 8.18% |

| Kostroma Oblast | 30.26% | 28.47% | 11.42% | 9.93% | 8.5% |

| Kurgan Oblast | 36.07% | 23.43% | 10.51% | 11.78% | 6.61% |

| Kursk Oblast | 43.48% | 19.89% | 8.04% | 10.67% | 6.82% |

| Leningrad Oblast | 43.1% | 18.41% | 9.75% | 8.34% | 6.59% |

| Lipetsk Oblast | 48.65% | 21.15% | 5.96% | 7.76% | 4.39% |

| Magadan Oblast | 50.08% | 20.67% | 4.91% | 8.95% | 5.23% |

| Moscow Oblast | 45.68% | 20.65% | 7.19% | 7.47% | 5.16% |

| Murmansk Oblast | 35.81% | 17.81% | 11.21% | 11.06% | 8.56% |

| Nizhny Novgorod Oblast | 49.95% | 19.2% | 8.55% | 7.14% | 5.18% |

| Novgorod Oblast | 32.51% | 21.33% | 14.37% | 9.24% | 7.63% |

| Novosibirsk Oblast | 35.25% | 25.86% | 6.94% | 9.61% | 8.71% |

| Omsk Oblast | 32.9% | 31.19% | 8.26% | 7.22% | 7.62% |

| Orenburg Oblast | 38.36% | 26.16% | 7.58% | 9.44% | 6.03% |

| Oryol Oblast | 38.83% | 21.86% | 10.16% | 8.8% | 5.99% |

| Penza Oblast | 56.21% | 17.24% | 6.09% | 7.5% | 4.89% |

| Pskov Oblast | 40.07% | 21.52% | 9.05% | 8.64% | 6.23% |

| Rostov Oblast | 51.59% | 20.19% | 6.42% | 6.97% | 5.17% |

| Ryazan Oblast | 47.79% | 19.99% | 8.22% | 6.79% | 5.65% |

| Samara Oblast | 44.3% | 23.29% | 6.32% | 7.45% | 5.63% |

| Saratov Oblast | 59.84% | 20.74% | 4.1% | 5.15% | 2.85% |

| Sakhalin Oblast | 35.73% | 28.63% | 5.2% | 8.89% | 9.07% |

| Sverdlovsk Oblast | 34.69% | 21.3% | 12.85% | 8.58% | 8.24% |

| Smolensk Oblast | 39.94% | 22.81% | 7.58% | 11.25% | 5.97% |

| Tambov Oblast | 56.92% | 15% | 4.72% | 4.87% | 2.45% |

| Tver Oblast | 35.4% | 23.04% | 9.97% | 9.88% | 6.61% |

| Tomsk Oblast | 32.7% | 22.43% | 8.52% | 12.06% | 9.36% |

| Tula Oblast | 52.88% | 16.85% | 7.49% | 6.61% | 5.44% |

| Tyumen Oblast | 51.33% | 13.5% | 10.24% | 11.53% | 4.48% |

| Ulyanovsk Oblast | 39.03% | 33.14% | 5% | 7.4% | 5.36% |

| Chelyabinsk Oblast | 34.31% | 19.68% | 17.25% | 7.83% | 8.3% |

| Yaroslavl Oblast | 29.72% | 22.74% | 19.2% | 8.97% | 7.86% |

| Moscow | 36.97% | 22.67% | 7.35% | 7.08% | 7.09% |

| St. Petersburg | 35.07% | 17.98% | 10.81% | 6.22% | 7.55% |

| Sevastopol | 56.45% | 12.62% | 7.55% | 8.57% | 5.3% |

| Jewish Autonomous Republic | 56.39% | 18.74% | 5.36% | 8.19% | 3.32% |

| Nenets Autonomous Okrug | 29.06% | 31.98% | 7.97% | 11% | 6.48% |

| Khanty‑Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug | 42.3% | 17.73% | 5.78% | 12.38% | 6.39% |

| Chukotka Autonomous Okrug | 46.71% | 12.49% | 6.26% | 15.16% | 4.95% |

| Yamalo‑Nenets Autonomous Okrug | 68.92% | 7.16% | 4.04% | 13.49% | 1.2% |

Despite United Russia’s continued official dominance, the 2016 and 2021 electoral campaigns differed significantly, with major changes manifested in the political landscape and dynamics.

The 2021 campaign was much tougher and competitive both on party lists and majoritarian districts. There is greater political differentiation among the regions, growing polarization in protest regions, and a sharp spike in opposition and dominance among the legal opposition from one party—the CPRF. We can expect that the authorities’ struggle with the CPRF will become one of the main flashpoints of Russian politics in the near future.

Against a backdrop of growing protest, for the first time since the 2000s, the authorities were forced to allow a fifth party, New People, into parliament, though that party’s political future and likely role remains to be seen.

[1] VTsIOM’s social well‑being indexes. https://wciom.ru/ratings/indeksy‑socialnogo-samochuvstvija

[2] Прокуратура потребовала признать ФБК и штабы Навального экстремистским [Prosecutor demands FBK and Navalny headquarters be recognized as extremist]. April 16, 2021. https://www.rbc.ru/politics/16/04/2021/6079b2bf9a794761d4e7fa83

[3]Российские власти сообщили о более чем 17 тысячах задержанных на зимних акциях 2021 года [ Russian authorities announce the arrest of over 17,000 during the winter 2021 protests]. June 11, 2021. https://ovdinfo.org/news/2021/06/11/rossiyskie‑vlasti-soobshchili‑o-bolee‑chem-17‑tysyachah-zaderzhannyh‑na-zimnih

[4] Последствия акций протеста из‑за заключения Навального. Хроника, часть 2. [Results of the protest over Navalny’s arrest. Chronicle, Part 2]. April 22, 2021 https://ovdinfo.org/news/2021/06/11/rossiyskie‑vlasti-soobshchili‑o-bolee‑chem-17‑tysyachah-zaderzhannyh‑na-zimnih

[5] Dyuryagina, K. «Открытая Россия» объявила о самоликвидации [Open Russia announces its self‑liquidation]. May 27, 2021. https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/4828390?from=hotnews

[6] «Новые лишенцы»: за что граждан России массово поражают в праве быть избранными на выборах в 2021 году. 22.06.2021. https://www.golosinfo.org/articles/145272

[7] https://wciom.ru/ratings/reiting‑politicheskikh-partii/

[8] Шпилькин С. От обнуления — к удвоению. // Новая газета. № 106 от 22 сентября 2021.

https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2021/09/21/ot‑obnuleniia-k‑udvoeniiu

[9] REV results: monitoring is impossible. https://roskomsvoboda.org/post/electronic‑voting-2021/

As the dust settles after the September elections into the State Duma, several important factors define the outlook for 2024, when Putin will likely seek to extend his Presidential tenure for another term— and, if in case of success, stay in power indefinitely

By Vladimir Milov

October 21, 2021

Article

Article The results of Russia’s September legislative elections are not only important in and of themselves, they provide a preview of how Vladimir Putin intends to govern and secure his own victory in the 2024 presidential elections

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

October 01, 2021

Article

Article The New People party has entered Russia’s State Duma, evoking many questions from outside observers, the first of which is very basic—does the sudden emergence and successful showing of New People demonstrate that it is possible to create new political parties for successful participation in elections?

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

October 05, 2021

As the dust settles after the September elections into the State Duma, several important factors define the outlook for 2024, when Putin will likely seek to extend his Presidential tenure for another term— and, if in case of success, stay in power indefinitely

By Vladimir Milov

October 21, 2021

Article

Article The results of Russia’s September legislative elections are not only important in and of themselves, they provide a preview of how Vladimir Putin intends to govern and secure his own victory in the 2024 presidential elections

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

October 01, 2021

Article

Article The New People party has entered Russia’s State Duma, evoking many questions from outside observers, the first of which is very basic—does the sudden emergence and successful showing of New People demonstrate that it is possible to create new political parties for successful participation in elections?

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

October 05, 2021