How Russian regions protested the war in Ukraine‑and why it cannot change anything

By Vadim Shtepa December 19, 2022

By Vadim Shtepa December 19, 2022

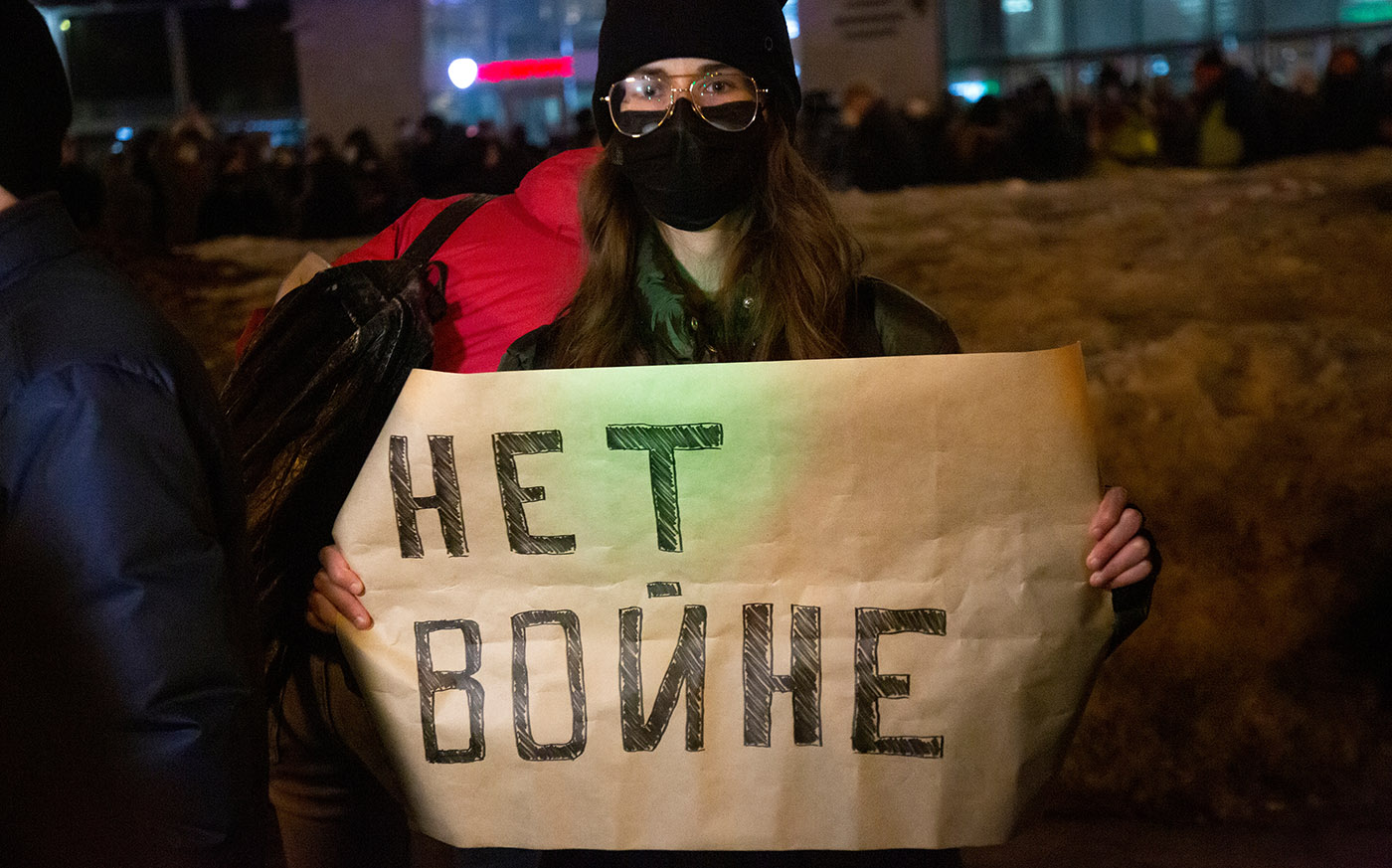

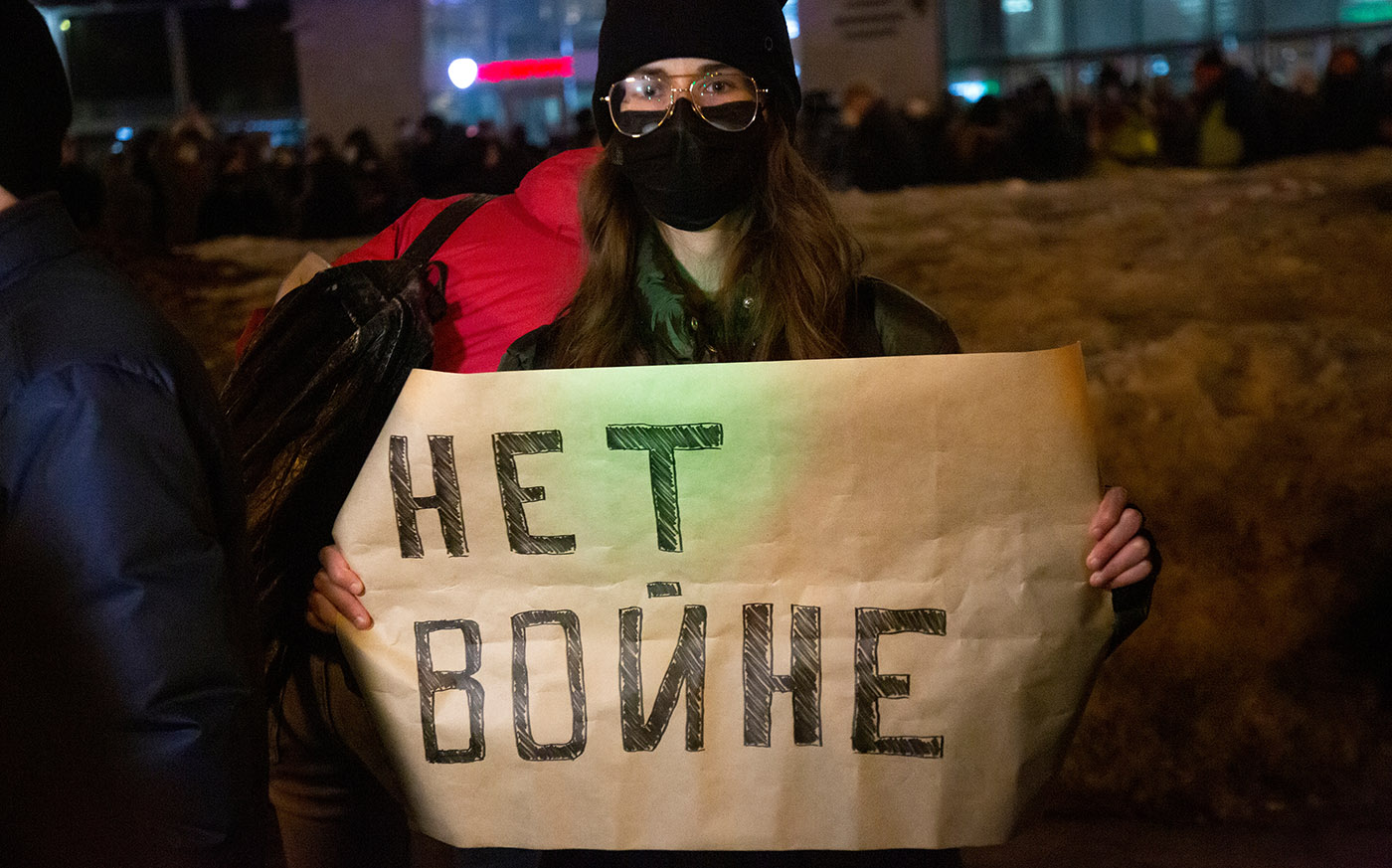

Anti‑war protests in Russia unfolded from the early hours of February 24, 2022. While millions did not take to the streets, tens of thousands of the Russian citizens actively resisted the aggression. They were unable to stop the militaristic madness or even to cool it down.

They are reproached for not being active enough, their participation not massive enough, but critics often forget to consider historical and political context of the Russian situation.

Residents of the Far East, Siberia and the Urals were the first to speak out against the war, taking to the streets on February 24 afternoon, when it was still early morning in the Russian capital, but tanks had already crossed the border of Ukraine.

At first, anti‑war protests were massive, taking place across almost all Russian cities. But on March 4, in three hasty readings at once, the State Duma adopted a law on “discrediting the Russian armed forces,“ which provides for harsh punishments of up to 15 years in prison.

According to OVD‑info, an independent human rights media project, by mid‑December 2022, the total number of detainees for anti‑war actions, has amounted to about 20,000 people.

In Khabarovsk, police detained a man standing in a solitary picket with a poster “Children should live in peace.” He suggested that “it is a shame to remove such a poster,” but it was nevertheless removed, and the picketer himself was taken to the police station. Since virtually any poster is now banned, protesters are trying to express their views in a different way.

Deputy of the Novosibirsk City Council Helga Pirogova came to the session wearing a Ukrainian embroidered shirt and a flower crown, which provoked a scandal among her colleagues who accused her of “betrayal.”

Lawyer Viktor Vorobyov, deputy at the parliament of the Republic of Komi, who spoke out against the war in the first days of Russia’s military aggression, was arrested for 15 days in violation of the laws on parliamentary immunity.

The Buryat Democratic Movement, banned in Russia, appealed to Russian servicemen that come originally from this republic to refuse the criminal orders of their commanders.

The independent Bashkir publicist Shamil Valiev posed a reasonable question: “Do we, the peoples of the Volga region, need this war, if today we, ourselves, do not have normal democratic self‑governance in our republics?”

In Petrozavodsk, the capital of Karelia, as elsewhere, protests have been dispersed since March. But the local residents found a creative way of “silent protest”: the trees and lanterns in the city are decorated with symbols of peace‑white paper cranes, which the security forces regularly remove, but the cranes reappear every morning.

In Tomsk, students are expelled from the university for speaking out against the war.

Literary critic Lyubov Summ was detained on Pushkinskaya Square in Moscow for reading Nikolai Nekrasov’s poem “As I hearken to the horrors of war,“ which is part of the school curriculum.

If all possibilities of peaceful anti‑war protest are blocked, it is not surprising that the protest takes on more radical forms. Since February, more than 50 attempts to set military enlistment offices on fire have been made in different regions of Russia.

And yet, these protest actions have no influence on the Russian government’s policies. This is the fundamental difference between the Russian situation and well‑known protests in the United States against the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 70s, which ultimately led to its end. This historical parallel helps to understand the reasons for what looks like a failure of the Russian protests.

In the United States, already in that era, a developed system of civil institutions capable of influencing the government had been put in place. There were Senators and House Representatives critical of the war. Here, an analogy can be drawn with the Ukrainian EuroMaidan in 2013–2014‑its supporters could be found in the Rada, which ensured the political representation of the protest.

Nothing of the kind can be said about Russia today. Not a single State Duma deputy dared to oppose the start of the war in February and Putin’s decree on mobilization in September. Only the above‑mentioned local deputies in Novosibirsk and the Komi Republic dared to do so.

Russia’s political system is not adequate to the public interests: while massive anti‑war protests took place in Moscow and St. Petersburg earlier this year, not a single deputy of the Moscow or St. Petersburg city assemblies spoke out to support them.

Anti‑war protests in Russia unfolded from the early hours of February 24, 2022. While millions did not take to the streets, tens of thousands of the Russian citizens actively resisted the aggression. They were unable to stop the militaristic madness or even to cool it down.

They are reproached for not being active enough, their participation not massive enough, but critics often forget to consider historical and political context of the Russian situation.

Residents of the Far East, Siberia and the Urals were the first to speak out against the war, taking to the streets on February 24 afternoon, when it was still early morning in the Russian capital, but tanks had already crossed the border of Ukraine.

At first, anti‑war protests were massive, taking place across almost all Russian cities. But on March 4, in three hasty readings at once, the State Duma adopted a law on “discrediting the Russian armed forces,” which provides for harsh punishments of up to 15 years in prison.

According to OVD‑info, an independent human rights media project, by mid‑December 2022, the total number of detainees for anti‑war actions, has amounted to about 20,000 people.

In Khabarovsk, police detained a man standing in a solitary picket with a poster “Children should live in peace.” He suggested that “it is a shame to remove such a poster,” but it was nevertheless removed, and the picketer himself was taken to the police station. Since virtually any poster is now banned, protesters are trying to express their views in a different way.

Deputy of the Novosibirsk City Council Helga Pirogova came to the session wearing a Ukrainian embroidered shirt and a flower crown, which provoked a scandal among her colleagues who accused her of “betrayal.“

Lawyer Viktor Vorobyov, deputy at the parliament of the Republic of Komi, who spoke out against the war in the first days of Russia’s military aggression, was arrested for 15 days in violation of the laws on parliamentary immunity.

The Buryat Democratic Movement, banned in Russia, appealed to Russian servicemen that come originally from this republic to refuse the criminal orders of their commanders.

The independent Bashkir publicist Shamil Valiev posed a reasonable question: “Do we, the peoples of the Volga region, need this war, if today we, ourselves, do not have normal democratic self‑governance in our republics?”

In Petrozavodsk, the capital of Karelia, as elsewhere, protests have been dispersed since March. But the local residents found a creative way of “silent protest”: the trees and lanterns in the city are decorated with symbols of peace‑white paper cranes, which the security forces regularly remove, but the cranes reappear every morning.

In Tomsk, students are expelled from the university for speaking out against the war.

Literary critic Lyubov Summ was detained on Pushkinskaya Square in Moscow for reading Nikolai Nekrasov’s poem “As I hearken to the horrors of war,” which is part of the school curriculum.

If all possibilities of peaceful anti‑war protest are blocked, it is not surprising that the protest takes on more radical forms. Since February, more than 50 attempts to set military enlistment offices on fire have been made in different regions of Russia.

And yet, these protest actions have no influence on the Russian government’s policies. This is the fundamental difference between the Russian situation and well‑known protests in the United States against the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 70s, which ultimately led to its end. This historical parallel helps to understand the reasons for what looks like a failure of the Russian protests.

In the United States, already in that era, a developed system of civil institutions capable of influencing the government had been put in place. There were Senators and House Representatives critical of the war. Here, an analogy can be drawn with the Ukrainian EuroMaidan in 2013–2014‑its supporters could be found in the Rada, which ensured the political representation of the protest.

Nothing of the kind can be said about Russia today. Not a single State Duma deputy dared to oppose the start of the war in February and Putin’s decree on mobilization in September. Only the above‑mentioned local deputies in Novosibirsk and the Komi Republic dared to do so.

Russia’s political system is not adequate to the public interests: while massive anti‑war protests took place in Moscow and St. Petersburg earlier this year, not a single deputy of the Moscow or St. Petersburg city assemblies spoke out to support them.

Paradoxically, today’s Russia, which calls itself a “democracy” and a “federation” in the Constitution, lacks the civic institutions that had once existed even in the Russian Empire‑for example, zemstvos (locally elected councils), which since 1860s had been an effective mechanism of local self‑government. While municipal elections do take place in modern Russia, the deputies’ powers are minimal, and local communities can’t even collect taxes on their territory‑everything is controlled by Moscow. And when they try to carry out independent political projects, their assembly can be dispersed.

At the same time, some Western observers reproach Russians for not protesting enough against the war. But these reproaches do not take into account the political dimension of the moment. Could one imagine mass protests against the Stalin regime in Soviet Union in 1939? Or in against the Hitler regime in Germany? Given complete destruction of civic institutions in Russia, the absence of free elections, the regime of state propaganda and censorship, any protest is doomed to be suppressed. Should observers from democratic countries, for whom civil liberties come naturally, demand “active resistance” from those who find themselves under totalitarian rule?

Despite all repressions, anti‑war resistance in Russia continues. It takes on new forms, in some places it develops into public criticism of the Russian state as such.

Take, for example, a bright and very revealing slogan in protests against mobilization in Dagestan where people blocked federal highways: “Ukraine did not attack us! Moscow attacked us!”

Ingush human rights activist Zarina Sautieva, currently a public policy fellow at the Wilson Center, writes that in her home republic, “attempts to forcibly conscript young people into the army are likely to meet with growing resistance from citizens, up to and including armed confrontation with authorities.“

The Kremlin, having unleashed a war against Ukraine, risks getting a “second front” in the Caucasus.

Still, the main form of protest against the war and mobilization was Russians’ mass exodus from the country. Up to one million people left in 2022 alone. Most often, they flee to post‑Soviet countries neighboring Russia, where a visa is not required for entry‑Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Georgia, Armenia.

And they relocate their businesses from different Russian regions and invest in the economies of these new home countries, while Russia falls deeper into international isolation.

This exodus, unprecedented in recent history, demonstrates that Russians feel that they cannot change their country’s politics on their own. And this situation calls into question the very existence of the Russian state. If one tries to imagine the post‑war period, it is likely that Russia will need to be re‑established as a state and a federation with the active support of the international community.

The catastrophe of the imperial war against Ukraine, as if coming from past eras, can only be overcome by the “whole world” effort.

Paradoxically, today’s Russia, which calls itself a “democracy” and a “federation” in the Constitution, lacks the civic institutions that had once existed even in the Russian Empire‑for example, zemstvos (locally elected councils), which since 1860s had been an effective mechanism of local self‑government. While municipal elections do take place in modern Russia, the deputies’ powers are minimal, and local communities can’t even collect taxes on their territory‑everything is controlled by Moscow. And when they try to carry out independent political projects, their assembly can be dispersed.

At the same time, some Western observers reproach Russians for not protesting enough against the war. But these reproaches do not take into account the political dimension of the moment. Could one imagine mass protests against the Stalin regime in Soviet Union in 1939? Or in against the Hitler regime in Germany? Given complete destruction of civic institutions in Russia, the absence of free elections, the regime of state propaganda and censorship, any protest is doomed to be suppressed. Should observers from democratic countries, for whom civil liberties come naturally, demand “active resistance” from those who find themselves under totalitarian rule?

Despite all repressions, anti‑war resistance in Russia continues. It takes on new forms, in some places it develops into public criticism of the Russian state as such.

Take, for example, a bright and very revealing slogan in protests against mobilization in Dagestan where people blocked federal highways: “Ukraine did not attack us! Moscow attacked us!”

Ingush human rights activist Zarina Sautieva, currently a public policy fellow at the Wilson Center, writes that in her home republic, “attempts to forcibly conscript young people into the army are likely to meet with growing resistance from citizens, up to and including armed confrontation with authorities.”

The Kremlin, having unleashed a war against Ukraine, risks getting a “second front” in the Caucasus.

Still, the main form of protest against the war and mobilization was Russians’ mass exodus from the country. Up to one million people left in 2022 alone. Most often, they flee to post‑Soviet countries neighboring Russia, where a visa is not required for entry‑Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Georgia, Armenia.

And they relocate their businesses from different Russian regions and invest in the economies of these new home countries, while Russia falls deeper into international isolation.

This exodus, unprecedented in recent history, demonstrates that Russians feel that they cannot change their country’s politics on their own. And this situation calls into question the very existence of the Russian state. If one tries to imagine the post‑war period, it is likely that Russia will need to be re‑established as a state and a federation with the active support of the international community.

The catastrophe of the imperial war against Ukraine, as if coming from past eras, can only be overcome by the “whole world” effort.

No one in Russia wants a long‑term war, and the mobilization for the war is unpopular

By Vladimir Milov

December 30, 2022

Article

Article Why the World Must Support Russians Fleeing Mobilization

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

October 03, 2022

Article

Article By Free Russia Foundation

June 21, 2023

No one in Russia wants a long‑term war, and the mobilization for the war is unpopular

By Vladimir Milov

December 30, 2022

Article

Article Why the World Must Support Russians Fleeing Mobilization

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

October 03, 2022

Article

Article By Free Russia Foundation

June 21, 2023