Via Dolorosa of Ukrainian Prisoners of War and Civilian Hostages

“Poshuk. Polon”: The fate of tens of thousands of military and civilian Ukrainians remains unknown

By Vladimir Zhbankov November 19, 2024

“Poshuk. Polon”: The fate of tens of thousands of military and civilian Ukrainians remains unknown

By Vladimir Zhbankov November 19, 2024

Torture and inhuman conditions in Russian prisons have long been a well‑known fact. Cruel treatment of Ukrainian prisoners of war in an aggregious violation of the Geneva convention is also a well‑known fact.

Access of human rights defenders and representatives of international humanitarian missions to Ukrainians detained in Russia and in the illegally occupied territories of Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson regions is a major problem.

But there are facts that often escape public attention: along with Ukrainian prisoners of war, Russian armed forces and representatives of paramilitary formations kidnap a large number of civilians who are not combatants and are not related to the armed forces of Ukraine and who have not committed any unlawful acts. The whereabouts of these civilians are usually unknown until they are charged and their cases are published by the courts.

Neglect, torture and isolation are systemic in the treatment of abducted/captured citizens of Ukraine.

Torture and inhuman conditions in Russian prisons have long been a well‑known fact. Cruel treatment of Ukrainian prisoners of war in an aggregious violation of the Geneva convention is also a well‑known fact.

Access of human rights defenders and representatives of international humanitarian missions to Ukrainians detained in Russia and in the illegally occupied territories of Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson regions is a major problem.

But there are facts that often escape public attention: along with Ukrainian prisoners of war, Russian armed forces and representatives of paramilitary formations kidnap a large number of civilians who are not combatants and are not related to the armed forces of Ukraine and who have not committed any unlawful acts. The whereabouts of these civilians are usually unknown until they are charged and their cases are published by the courts.

Neglect, torture and isolation are systemic in the treatment of abducted/captured citizens of Ukraine.

The “Poshuk. Polon” project has been supporting Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilian hostages since the first days of Russian full scale invasion.

As part of this work, “Poshuk. Polon” has collected a vast amount of data on the fate of Ukrainians from the moment they find themselves in the custody of Russian forces or their proxies, to their imprisonment in Russian penal colonies, and in some lucky cases, their return home, or in the very tragic cases, their deaths.

Russian authorities purposefully violate international humanitarian law. A notable aspect of Russia’s repressive practices toward Ukrainian citizens is the near‑total disregard for the distinction between military personnel and civilians.

The “Poshuk. Polon” project has been supporting Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilian hostages since the first days of Russian full scale invasion.

As part of this work, “Poshuk. Polon” has collected a vast amount of data on the fate of Ukrainians from the moment they find themselves in the custody of Russian forces or their proxies, to their imprisonment in Russian penal colonies, and in some lucky cases, their return home, or in the very tragic cases, their deaths.

Russian authorities purposefully violate international humanitarian law. A notable aspect of Russia’s repressive practices toward Ukrainian citizens is the near‑total disregard for the distinction between military personnel and civilians.

While military personnel are usually charged with extremism, civilians are more frequently accused of terrorism. Sentences typically range from over ten years to life in prison. Given the horrific conditions in Russian prisons and the particularly harsh treatment of Ukrainians, the chances of surviving even ten years are slim.

While military personnel are usually charged with extremism, civilians are more frequently accused of terrorism. Sentences typically range from over ten years to life in prison. Given the horrific conditions in Russian prisons and the particularly harsh treatment of Ukrainians, the chances of surviving even ten years are slim.

It is impossible to determine the exact number of people who have been abducted and are being held in this manner, as the Russian authorities deliberately conceal this information, but “Poshuk. Polon” conservatively assesses this number to be in the tens of thousands.

It is impossible to determine the exact number of people who have been abducted and are being held in this manner, as the Russian authorities deliberately conceal this information, but “Poshuk. Polon” conservatively assesses this number to be in the tens of thousands.

The ordeals of Ukrainian prisoners of war begin in different ways but soon follow a common trajectory. Soldiers may be captured during combat or military maneuvers, sometimes when they are unconscious. In 2022, reports from relatives and other sources frequently mentioned cases of memory loss and varying degrees of injuries.

What happens next largely depends on the combat situation and the goodwill of Russian commanders or their paramilitary proxies (including rogue private military companies).

Wounded Ukrainian soldiers may be killed or taken to Russian hospitals, where they may receive limited medical care. Independent international observers, human rights defenders, and lawyers have no access to these hospitals, and the captives are kept incommunicado for extended periods, regardless of whether they are injured or relatively healthy (there are no fully healthy prisoners due to the unsafe prison conditions).

The ordeals of Ukrainian prisoners of war begin in different ways but soon follow a common trajectory. Soldiers may be captured during combat or military maneuvers, sometimes when they are unconscious. In 2022, reports from relatives and other sources frequently mentioned cases of memory loss and varying degrees of injuries.

What happens next largely depends on the combat situation and the goodwill of Russian commanders or their paramilitary proxies (including rogue private military companies).

Wounded Ukrainian soldiers may be killed or taken to Russian hospitals, where they may receive limited medical care. Independent international observers, human rights defenders, and lawyers have no access to these hospitals, and the captives are kept incommunicado for extended periods, regardless of whether they are injured or relatively healthy (there are no fully healthy prisoners due to the unsafe prison conditions).

After a partial recovery, wounded prisoners are usually transferred to the Russian Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN) system, often ending up in pretrial detention centers (SIZO). There, they join other Ukrainian prisoners who never made it to the hospital.

Both civilian hostages and prisoners of war may be kept incommunicado for years during “pre‑trial detention”. The only exceptions are criminal cases and public trials (and not all of the trials are public) and public records issued when the detainees are accused or convicted.

However, according to our estimates, during the entire period of Russia’s full‑scale invasion of Ukraine, human right defenders ha managed to get information about no more than 3–5% of the prisoners.

After a partial recovery, wounded prisoners are usually transferred to the Russian Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN) system, often ending up in pretrial detention centers (SIZO). There, they join other Ukrainian prisoners who never made it to the hospital.

Both civilian hostages and prisoners of war may be kept incommunicado for years during “pre‑trial detention”. The only exceptions are criminal cases and public trials (and not all of the trials are public) and public records issued when the detainees are accused or convicted.

However, according to our estimates, during the entire period of Russia’s full‑scale invasion of Ukraine, human right defenders ha managed to get information about no more than 3–5% of the prisoners.

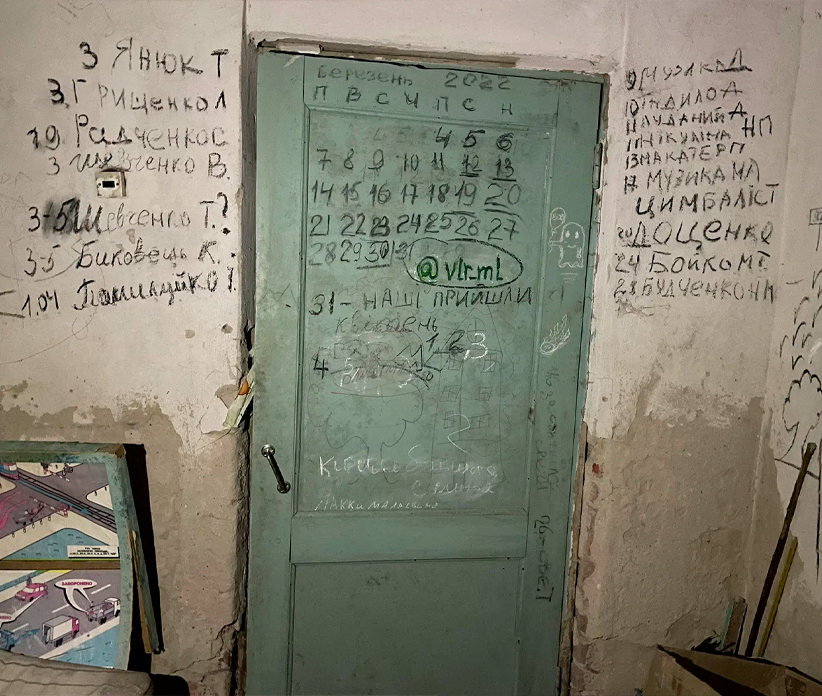

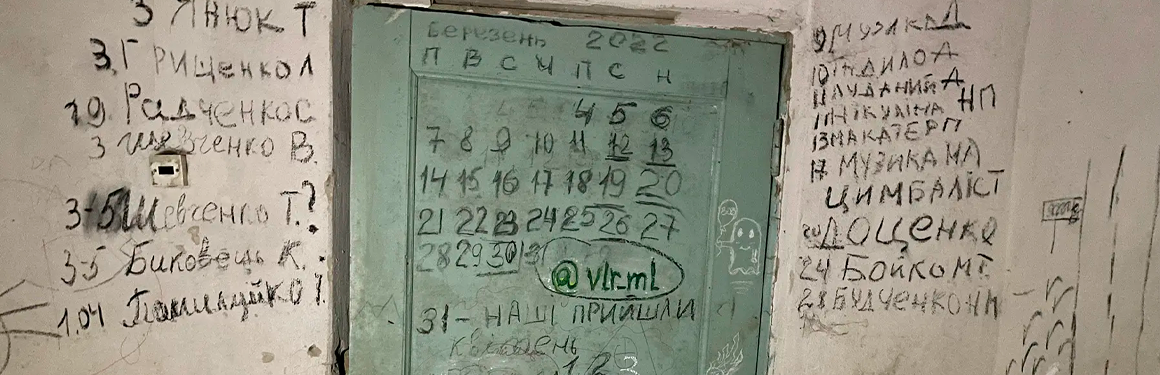

Relatively healthy prisoners, those deemed as such, or those whose wounds are considered by Russian commanders unworthy of treatment, are initially placed in what is known as “the basement” (“podval” in Russian, an established term).

This is typically a facility not meant for human confinement, such as a factory, a warehouse, a barn, a basement of a residential or public building, or any other location where many people can be effectively isolated.

Relatively healthy prisoners, those deemed as such, or those whose wounds are considered by Russian commanders unworthy of treatment, are initially placed in what is known as “the basement” (“podval” in Russian, an established term).

This is typically a facility not meant for human confinement, such as a factory, a warehouse, a barn, a basement of a residential or public building, or any other location where many people can be effectively isolated.

The condition of civilian hostages, especially in the early stages, is even more perilous. After an occupation of a settlement by Russian forces, Ukrainian civilians may be detained at their homes, at work, while using public transport, or in any public place either by military or paramilitary forces or by local police who have switched sides.

Civilians may also be subjected to the so‑called “filtration” process conducted by the Russian authorities in the course of forced evacuations. Evacuees are placed in special camps, where conditions are far below internationally‑mandated standards, and subjected to «verification procedures.“ Almost anything can serve as a reason for arrest.

The risk increases if a person:

The condition of civilian hostages, especially in the early stages, is even more perilous. After an occupation of a settlement by Russian forces, Ukrainian civilians may be detained at their homes, at work, while using public transport, or in any public place either by military or paramilitary forces or by local police who have switched sides.

Civilians may also be subjected to the so‑called “filtration” process conducted by the Russian authorities in the course of forced evacuations. Evacuees are placed in special camps, where conditions are far below internationally‑mandated standards, and subjected to «verification procedures.” Almost anything can serve as a reason for arrest.

The risk increases if a person:

Torture is a real risk throughout the entire journey of a prisoner, but it is typically most severe during the early stages.

Torture methods perpetrated against Ukrainian citizens include:

Torture is a real risk throughout the entire journey of a prisoner, but it is typically most severe during the early stages.

Torture methods perpetrated against Ukrainian citizens include:

Each occupying unit has its own methods of torture, which can be prolonged and cause irreversible damage, such as gangrene.

The period spent in “the basement” can range from days to months. Torture is most intense during the first week, after which beatings and other violence may become sporadic but still frequent. Some detainees perish during this stage, especially if held by paramilitary groups, although the exact number is unknown.

Each occupying unit has its own methods of torture, which can be prolonged and cause irreversible damage, such as gangrene.

The period spent in “the basement” can range from days to months. Torture is most intense during the first week, after which beatings and other violence may become sporadic but still frequent. Some detainees perish during this stage, especially if held by paramilitary groups, although the exact number is unknown.

Having survived the initial stage, some detainees are subjected to long‑term forced labor by Russian military and paramilitary forces. Sexual violence, severe torture, and injurious forced labor are common in these situations. Some testimonies suggest that a significant portion of the so‑called “Surovikin Line” was built by civilian hostages and prisoners of war.

Having survived the initial stage, some detainees are subjected to long‑term forced labor by Russian military and paramilitary forces. Sexual violence, severe torture, and injurious forced labor are common in these situations. Some testimonies suggest that a significant portion of the so‑called “Surovikin Line” was built by civilian hostages and prisoners of war.

Living conditions in these camps are atrocious, and the detainees are often forced to perform life‑threatening tasks, such as locating and disabling anti‑tank mines by hand. Food is scarce, often containing expired products, while medical care is non‑existent. The exact number of victims of forced labor and their ultimate fate is hard to estimate.

Some captives are transferred to the FSIN facilities including pretrial detention centers (SIZO), where they are held in special isolated sections administered by the military police. Such placement allows the Russian authorities to fabricate criminal charges, exert pressure on detainees, and force confessions or self‑incrimination.

The charges vary, but the most common accusations include violent crimes, violations of the laws of war, terrorism, and extremism. Investigation and court documents tend to consistently avoid mentioning the existence of the Ukrainian army, labeling its units as extremist organizations instead.

Living conditions in these camps are atrocious, and the detainees are often forced to perform life‑threatening tasks, such as locating and disabling anti‑tank mines by hand. Food is scarce, often containing expired products, while medical care is non‑existent. The exact number of victims of forced labor and their ultimate fate is hard to estimate.

Some captives are transferred to the FSIN facilities including pretrial detention centers (SIZO), where they are held in special isolated sections administered by the military police. Such placement allows the Russian authorities to fabricate criminal charges, exert pressure on detainees, and force confessions or self‑incrimination.

The charges vary, but the most common accusations include violent crimes, violations of the laws of war, terrorism, and extremism. Investigation and court documents tend to consistently avoid mentioning the existence of the Ukrainian army, labeling its units as extremist organizations instead.

Paradoxically, a fabricated criminal case along with a subsequent trial can sometimes improve a detainee’s condition.

Paradoxically, a fabricated criminal case along with a subsequent trial can sometimes improve a detainee’s condition.

The FSIN (Federal Penitentiary Service) facilities involved in this process are located throughout the occupied territories and inside Russia, usually in its European part. In several cases, however, civilian hostages were transported to as far as Khabarovsk during the investigation phase.

Sometimes, although not frequently, prisoners of war and civilian hostages are sent to specialized detention centers, such as the FSB‑run Lefortovo prison, immediately after the “basement” stage.

The FSIN (Federal Penitentiary Service) facilities involved in this process are located throughout the occupied territories and inside Russia, usually in its European part. In several cases, however, civilian hostages were transported to as far as Khabarovsk during the investigation phase.

Sometimes, although not frequently, prisoners of war and civilian hostages are sent to specialized detention centers, such as the FSB‑run Lefortovo prison, immediately after the “basement” stage.

Criminal cases against Ukrainian prisoners and civilian hostages are generally handled by the Southern District Military Court in Rostov. In such instances, detainees are typically held in SIZO‑1 and SIZO‑5 in Rostov‑on-Don. While conditions there are certainly below basic sanitary standards, they are better than those of the SIZOs in Donetsk and similar facilities, allowing some prisoners to begin recovering from torture.

Criminal cases against Ukrainian prisoners and civilian hostages are generally handled by the Southern District Military Court in Rostov. In such instances, detainees are typically held in SIZO‑1 and SIZO‑5 in Rostov‑on-Don. While conditions there are certainly below basic sanitary standards, they are better than those of the SIZOs in Donetsk and similar facilities, allowing some prisoners to begin recovering from torture.

Alternative locations uncovered by Poshuk. Polon include the SIZO in Taganrog. In violation of all applicable legal norms, lawyers are not allowed into this facility. It is common for prisoners to be moved from Rostov to Taganrog when the prosecution is dissatisfied with the case’s progress.

Criminal cases are also tried in courts in Donetsk, Simferopol, other occupied locations in Ukraine, as well as in Russia. After the trial, prisoners are transferred to permanent locations to serve their sentences.

This stage presents a critical opening to provide professional legal assistance to prisoners of war and civilian hostages. Independent lawyers can meaningfully protect prisoners' rights in detention, securing access to medical care, facilitating communication with their families, and facilitating deliveries of care packages and money transfers. Without exaggeration, the involvement of independent lawyers can save lives.

Alternative locations uncovered by Poshuk. Polon include the SIZO in Taganrog. In violation of all applicable legal norms, lawyers are not allowed into this facility. It is common for prisoners to be moved from Rostov to Taganrog when the prosecution is dissatisfied with the case’s progress.

Criminal cases are also tried in courts in Donetsk, Simferopol, other occupied locations in Ukraine, as well as in Russia. After the trial, prisoners are transferred to permanent locations to serve their sentences.

This stage presents a critical opening to provide professional legal assistance to prisoners of war and civilian hostages. Independent lawyers can meaningfully protect prisoners' rights in detention, securing access to medical care, facilitating communication with their families, and facilitating deliveries of care packages and money transfers. Without exaggeration, the involvement of independent lawyers can save lives.

It is essential to monitor the problem of civilian hostage‑taking and to begin work toward the establishment of a mechanism for their release and exchange. At present, obtaining information and providing assistance to Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilian hostages requires direct participation of Russian civil society.

Russian activists and human rights defenders engaged in assisting Ukrainian citizens on the territory of the Russian Federation assume enormous risks, are subjected to psychological pressure and threats of persecution. They need support while maintaining anonymity and ensuring security protocols.

It is essential to monitor the problem of civilian hostage‑taking and to begin work toward the establishment of a mechanism for their release and exchange. At present, obtaining information and providing assistance to Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilian hostages requires direct participation of Russian civil society.

Russian activists and human rights defenders engaged in assisting Ukrainian citizens on the territory of the Russian Federation assume enormous risks, are subjected to psychological pressure and threats of persecution. They need support while maintaining anonymity and ensuring security protocols.

Realizing the serious limitations in the maneuver space encountered by the International Red Cross and other monitoring missions who depend on the goodwill of the Russian Federation, in complying with the Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, Free Russia Foundation calls for the establishment of alternative channels to access and continuously monitor the conditions of Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilian hostages held by the Russian government.

The international community must be persistent and not abandon attempts to release Ukrainian citizens from Russian prisons and captivity, as it means saving lives. This should be a central theme of any negotiations with Russia to preclude the Kremlin from using these hostages to exert pressure on Ukraine and the West.

Realizing the serious limitations in the maneuver space encountered by the International Red Cross and other monitoring missions who depend on the goodwill of the Russian Federation, in complying with the Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, Free Russia Foundation calls for the establishment of alternative channels to access and continuously monitor the conditions of Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilian hostages held by the Russian government.

The international community must be persistent and not abandon attempts to release Ukrainian citizens from Russian prisons and captivity, as it means saving lives. This should be a central theme of any negotiations with Russia to preclude the Kremlin from using these hostages to exert pressure on Ukraine and the West.

How far can Putin go in militarizing Russia? What are the weaknesses of his approach?

By Free Russia Foundation

April 19, 2024

Article

Article Putin’s difficulties are plenty and mounting

By Vladimir Milov

June 04, 2024

Article

Article What are the trends in Russian public opinion regarding the war and support for the Putin regime?

By Vladimir Milov

December 11, 2023

How far can Putin go in militarizing Russia? What are the weaknesses of his approach?

By Free Russia Foundation

April 19, 2024

Article

Article Putin’s difficulties are plenty and mounting

By Vladimir Milov

June 04, 2024

Article

Article What are the trends in Russian public opinion regarding the war and support for the Putin regime?

By Vladimir Milov

December 11, 2023