In Their Own Words: Russian Officials Openly Describe the Dire State of the Russian Economy

By Vladimir Milov July 03, 2024

By Vladimir Milov July 03, 2024

It is widely assumed by Western media and experts that Vladimir Putin is strong, self‑assured, and possesses the resources for an everlasting warfare against Ukraine and the “collective West.”

More often than not they would claim that “Russia’s economy is thriving and weathering the sanctions,” that “Russia has unlimited manpower to wage the war,” and that “Putin has built a military economy capable of sustaining long‑term combat.”

It is widely assumed by Western media and experts that Vladimir Putin is strong, self‑assured, and possesses the resources for an everlasting warfare against Ukraine and the “collective West.”

More often than not they would claim that “Russia’s economy is thriving and weathering the sanctions,” that “Russia has unlimited manpower to wage the war,” and that “Putin has built a military economy capable of sustaining long‑term combat.”

If you are depressed by this grim view, there’s an easily accessible remedy: you should pay more attention to what Russian officials are actually saying about their country’s economic, social, and military situation.

Although the overall tone of Russian top functionaries and businesspeople is marked by fanfare and aims to reaffirm strength, they frequently have a sudden slip of the tongue, admitting severe problems and multiple crises the country is facing.

We have compiled a collection of such most recent quotes that paint a totally different, much darker and desperate picture of the real conditions and trends in Russia than many Putin‑confident Western commentators tend to give.

If you are depressed by this grim view, there’s an easily accessible remedy: you should pay more attention to what Russian officials are actually saying about their country’s economic, social, and military situation.

Although the overall tone of Russian top functionaries and businesspeople is marked by fanfare and aims to reaffirm strength, they frequently have a sudden slip of the tongue, admitting severe problems and multiple crises the country is facing.

We have compiled a collection of such most recent quotes that paint a totally different, much darker and desperate picture of the real conditions and trends in Russia than many Putin‑confident Western commentators tend to give.

This annual event is supposed to be the main show of Russia’s force and defiance in the face of isolation and pressure, the most important Potemkin village of Putin’s era.

However, if you read between the lines and listen carefully to what was said in St. Petersburg this time, the reality would look very different.

This annual event is supposed to be the main show of Russia’s force and defiance in the face of isolation and pressure, the most important Potemkin village of Putin’s era.

However, if you read between the lines and listen carefully to what was said in St. Petersburg this time, the reality would look very different.

In his SPIEF speech, Putin boasted about the new World Bank data identifying Russia as the world’s fourth largest economy in terms of purchasing power parity adjusted GDP.

The irony lies in the fact that Russia had reached this position as long as three years ago, which only became evident thanks to the latest PPP recalculations, showing how opaque these are.

Andrey Makarov, Chairman of the State Duma Committee on Budget and Taxes and a prominent member of the ruling United Russia party, all but mocked Putin’s bravado, asking rhetorically why no one had noticed that Russia had been the world’s fourth‑largest economy in terms of purchasing power parity for three years already: “Because it doesn’t affect anything.”

The parliamentarian noted that it would make more sense to talk about real issues that matter to Russians — like living standards.

In his SPIEF speech, Putin boasted about the new World Bank data identifying Russia as the world’s fourth largest economy in terms of purchasing power parity adjusted GDP.

The irony lies in the fact that Russia had reached this position as long as three years ago, which only became evident thanks to the latest PPP recalculations, showing how opaque these are.

Andrey Makarov, Chairman of the State Duma Committee on Budget and Taxes and a prominent member of the ruling United Russia party, all but mocked Putin’s bravado, asking rhetorically why no one had noticed that Russia had been the world’s fourth‑largest economy in terms of purchasing power parity for three years already: “Because it doesn’t affect anything.”

The parliamentarian noted that it would make more sense to talk about real issues that matter to Russians — like living standards.

Herman Gref, former Russia’s Minister of Economic Development and Trade and the CEO of Sberbank, Russia’s biggest bank, went further, saying that Russia’s current economic model was “vulnerable” and “exhaustible.”

It is based on the injection of budget funds and credit into consumption, which is followed neither by increased domestic production of goods nor by increased economic complexity but rather results in inflation and decreased productivity.

Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Chernyshenko, while veiledly dismissing Russia’s fourth place among the global economies by GDP (PPP), acknowledged “a terrible demographic pit” looming in Russia along with the fact that by 2030 a labor shortage could reach 2.4 million people.

Herman Gref, former Russia’s Minister of Economic Development and Trade and the CEO of Sberbank, Russia’s biggest bank, went further, saying that Russia’s current economic model was “vulnerable” and “exhaustible.”

It is based on the injection of budget funds and credit into consumption, which is followed neither by increased domestic production of goods nor by increased economic complexity but rather results in inflation and decreased productivity.

Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Chernyshenko, while veiledly dismissing Russia’s fourth place among the global economies by GDP (PPP), acknowledged “a terrible demographic pit” looming in Russia along with the fact that by 2030 a labor shortage could reach 2.4 million people.

He said that the government is working on improving the birth rate that must increase from 1.4 to 1.8. but would not “increase just because the government made a decision.” Chernyshenko concluded his bleak speech by stating that the only hope was the development of AI: “At this point we all believe that only AI will save us, because nothing else can.”

Andrey Makarov, however, remained sceptical: “I am firmly convinced that artificial intelligence will not help those who lack that of their own.”

He said that the government is working on improving the birth rate that must increase from 1.4 to 1.8. but would not “increase just because the government made a decision.” Chernyshenko concluded his bleak speech by stating that the only hope was the development of AI: “At this point we all believe that only AI will save us, because nothing else can.”

Andrey Makarov, however, remained sceptical: “I am firmly convinced that artificial intelligence will not help those who lack that of their own.”

First Deputy Prime Minister Denis Manturov admitted that, despite heavy recruitment efforts and an increase of salaries, the Russian arms industry faced shortage of 160,000 skilled personnel.

In her statement made a few hours after Putin’s SPIEF speech, Elvira Nabiullina, Governor of the Central Bank of Russia, mentioned a risk “that labour shortages will not be easing. So far, there are no signals that the labour market tightness is weakening.”

First Deputy Prime Minister Denis Manturov admitted that, despite heavy recruitment efforts and an increase of salaries, the Russian arms industry faced shortage of 160,000 skilled personnel.

In her statement made a few hours after Putin’s SPIEF speech, Elvira Nabiullina, Governor of the Central Bank of Russia, mentioned a risk “that labour shortages will not be easing. So far, there are no signals that the labour market tightness is weakening.”

More dark clouds gathered over SPIEF discussions of the Russian economy’s future as participants touched upon a growing scarcity of budget resources, destructive impacts of the state’s interventionism, a lack of property rights protection, and a severe increase of taxes whose point is to make ends meet.

Russia’s Minister of Economic Development Maxim Reshetnikov admitted that “appetites [for state funding] significantly exceed available resources.”

At the same time, the recent decision of the Russian government to raise taxes in 2024 by approximately 1,5% of GDP (about two thirds of which are contingent on raising of corporate profit tax rate from 20% to 25%) was met with fiery criticism.

More dark clouds gathered over SPIEF discussions of the Russian economy’s future as participants touched upon a growing scarcity of budget resources, destructive impacts of the state’s interventionism, a lack of property rights protection, and a severe increase of taxes whose point is to make ends meet.

Russia’s Minister of Economic Development Maxim Reshetnikov admitted that “appetites [for state funding] significantly exceed available resources.”

At the same time, the recent decision of the Russian government to raise taxes in 2024 by approximately 1,5% of GDP (about two thirds of which are contingent on raising of corporate profit tax rate from 20% to 25%) was met with fiery criticism.

Alexey Mordashov, the owner of Severstal steel company and Russia’s fourth wealthiest businessman according to Forbes, lambasted the government’s continuous tax hiking policy without mincing words:

Alexey Mordashov, the owner of Severstal steel company and Russia’s fourth wealthiest businessman according to Forbes, lambasted the government’s continuous tax hiking policy without mincing words:

“Every year we talk about the need for a stable tax system. We talk and talk, I would say, with passion, sincerely convincing each other of the need for this. And every time we state that something is not quite right. … The killer is the continuation of the conversation about trust that we are having today… We see the constant introduction of new levies. I will say something absolutely obvious and absolutely banal, but, unfortunately, we somehow do not take it into account: all this undermines trust, undermines our confidence… And so you work and work, earn money, and suddenly someone very respected looks at all this and says: your profitability is kind of too high. So this someone introduces a tax, it remains for many years, and nobody cancels it. It simply undermines motivation. And it undermines our ability to plan for the future.”

“Every year we talk about the need for a stable tax system. We talk and talk, I would say, with passion, sincerely convincing each other of the need for this. And every time we state that something is not quite right. … The killer is the continuation of the conversation about trust that we are having today… We see the constant introduction of new levies. I will say something absolutely obvious and absolutely banal, but, unfortunately, we somehow do not take it into account: all this undermines trust, undermines our confidence… And so you work and work, earn money, and suddenly someone very respected looks at all this and says: your profitability is kind of too high. So this someone introduces a tax, it remains for many years, and nobody cancels it. It simply undermines motivation. And it undermines our ability to plan for the future.”

Herman Gref echoes him:

Herman Gref echoes him:

“An increase in expenses due to an increase in taxes leads to a drop in GDP by 0.47% if taxes are raised by 1% of GDP. It implies that there is nothing left to debate here: private investments are at least 2–2.5 times more effective than public ones. Therefore, any increase in taxes is a deduction from GDP, no matter what we mean.”

“An increase in expenses due to an increase in taxes leads to a drop in GDP by 0.47% if taxes are raised by 1% of GDP. It implies that there is nothing left to debate here: private investments are at least 2–2.5 times more effective than public ones. Therefore, any increase in taxes is a deduction from GDP, no matter what we mean.”

The discussion was summed up by Andrey Makarov who highlighted the ruined trust in Russian government policies, a lack of motivation for private capital to invest, and the total inefficiency of the state‑run economy:

The discussion was summed up by Andrey Makarov who highlighted the ruined trust in Russian government policies, a lack of motivation for private capital to invest, and the total inefficiency of the state‑run economy:

“First we give money to produce a product, then we give money so that the state buys this product. Then we give money to build a warehouse to store the product because nobody needs it. Then comes the fourth stage: we give money to dispose of this product because nobody needs it.”

“First we give money to produce a product, then we give money so that the state buys this product. Then we give money to build a warehouse to store the product because nobody needs it. Then comes the fourth stage: we give money to dispose of this product because nobody needs it.”

The only viable alternative, as Makarov sees it, is to stimulate private investment, but investors are scared off by the government’s wild nationalization spree and utter disregard for the rule of law.

He explicitly mentioned the recent nationalization of Solikamsk Magnesium Plant shares owned by bona fide purchasers, observing sardonically that “the prosecutor’s stand is getting closer and closer to the conference hall.”

The only viable alternative, as Makarov sees it, is to stimulate private investment, but investors are scared off by the government’s wild nationalization spree and utter disregard for the rule of law.

He explicitly mentioned the recent nationalization of Solikamsk Magnesium Plant shares owned by bona fide purchasers, observing sardonically that “the prosecutor’s stand is getting closer and closer to the conference hall.”

As some at SPIEF said, the event everyone was waiting for took place outside St. Petersburg, in Moscow, where Elvira Nabiullina held a press conference following a regular meeting of the Central Bank’s board dedicated to the interest rate policy.

Nabiullina was forced to start the press conference for 6:30 pm instead of the standard 3 pm to make sure she didn’t interfere in Putin’s speech with bad news about inflation.

Remarkably, Putin had made no reference to inflation in Russia, choosing to mention this concern only in connection with the United States.

Nabiullina’s address, however, was quite sobering: inflation kept raging, almost a year of the Central Bank’s exceptionally tough monetary policies hadn’t been able to cool it, the balance of risks remained pro‑inflationary, and if the situation didn’t change by the end of July, when the Bank was supposed to have its next meeting to discuss the interest rate policy, Nabiullina foresaw a “considerable” increase of the key rate.

Since then, things got even worse; inflation reached the year’s record high of 0,22% per week, increasing to 8,6% in annualized terms by end‑June.

As some at SPIEF said, the event everyone was waiting for took place outside St. Petersburg, in Moscow, where Elvira Nabiullina held a press conference following a regular meeting of the Central Bank’s board dedicated to the interest rate policy.

Nabiullina was forced to start the press conference for 6:30 pm instead of the standard 3 pm to make sure she didn’t interfere in Putin’s speech with bad news about inflation.

Remarkably, Putin had made no reference to inflation in Russia, choosing to mention this concern only in connection with the United States.

Nabiullina’s address, however, was quite sobering: inflation kept raging, almost a year of the Central Bank’s exceptionally tough monetary policies hadn’t been able to cool it, the balance of risks remained pro‑inflationary, and if the situation didn’t change by the end of July, when the Bank was supposed to have its next meeting to discuss the interest rate policy, Nabiullina foresaw a “considerable” increase of the key rate.

Since then, things got even worse; inflation reached the year’s record high of 0,22% per week, increasing to 8,6% in annualized terms by end‑June.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg: according to ROMIR, a research company that has been specializing in the Russian consumer market surveys for many years, the FMCG (fast‑moving consumer goods) index — the price growth rate for all basic consumer goods an average Russian buys daily in a grocery store — rose by 34,4% year over year in May 2024, fuelling doubts over the reliability of Russia’s official inflation calculation methodology.

Under these circumstances, the Bank of Russia is, indeed, a stone’s throw away from significantly raising the key rate in July and thus further harming economic recovery by limiting growth.

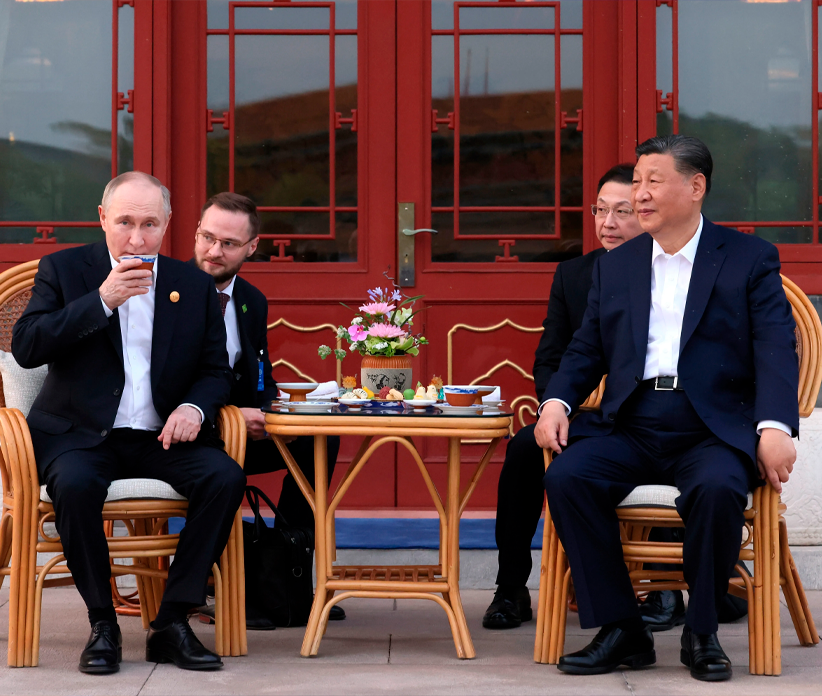

Another major issue is the ongoing blocking of transactions and payments with Russian exporters and importers by banks of third countries, including, most importantly, China. Chinese and other banks are afraid of the US secondary sanctions and keep massively suspending any transactions with Russian counterparts.

This measure severely impairs Russia’s ability to pay for critical imports of industrial components and technology, which prompted Maxim Reshetnikov, Russia’s Minister of Economic Development, to admit that it was “a little disconcerting” that imports had slowed down in the second quarter; “a suspicion” that investment imports were affected was “also alarming.” Putin’s visit to China in May had not helped to find a solution.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg: according to ROMIR, a research company that has been specializing in the Russian consumer market surveys for many years, the FMCG (fast‑moving consumer goods) index — the price growth rate for all basic consumer goods an average Russian buys daily in a grocery store — rose by 34,4% year over year in May 2024, fuelling doubts over the reliability of Russia’s official inflation calculation methodology.

Under these circumstances, the Bank of Russia is, indeed, a stone’s throw away from significantly raising the key rate in July and thus further harming economic recovery by limiting growth.

Another major issue is the ongoing blocking of transactions and payments with Russian exporters and importers by banks of third countries, including, most importantly, China. Chinese and other banks are afraid of the US secondary sanctions and keep massively suspending any transactions with Russian counterparts.

This measure severely impairs Russia’s ability to pay for critical imports of industrial components and technology, which prompted Maxim Reshetnikov, Russia’s Minister of Economic Development, to admit that it was “a little disconcerting” that imports had slowed down in the second quarter; “a suspicion” that investment imports were affected was “also alarming.” Putin’s visit to China in May had not helped to find a solution.

In light of the severity of the matter Vladimir Chistyukhin, the Bank of Russia’s First Deputy Governor, declared at the St. Petersburg International Legal Forum in late June that Russian economy would face nothing short of „death“ if the problem wasn’t resolved soon.

Maybe all these complications exist only because Putin has concentrated all his efforts on building a war machine focused on conquering Ukraine, and Russia’s military economy is contrarily thriving? Nothing of the sort.

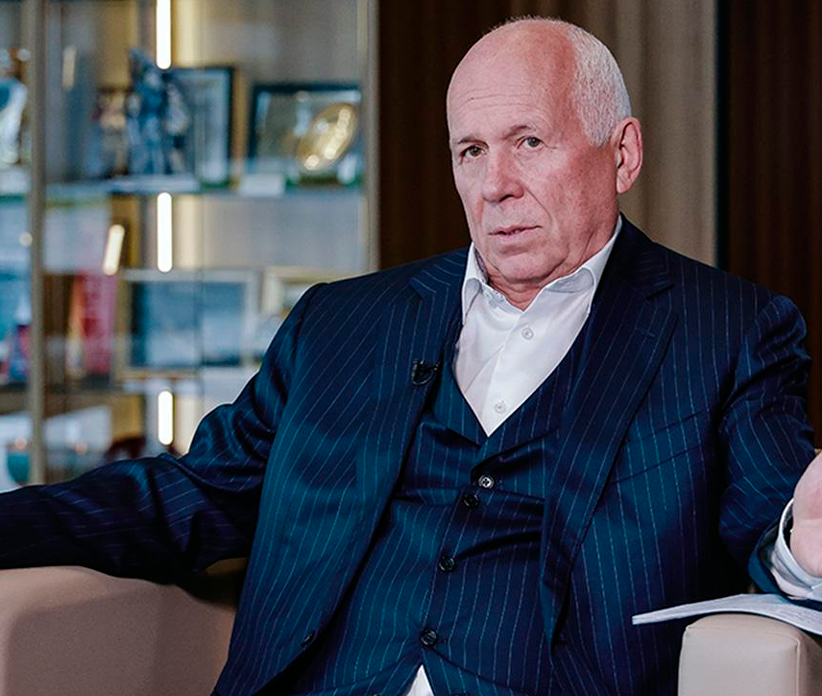

In a May 2024 interview with RBC, Sergey Chemezov, Putin’s most powerful military oligarch and the CEO of Rostec, a major industrial conglomerate that is Russia’s biggest weapons producer, conceded that the situation in the Russian arms industry was quite dismal.

In light of the severity of the matter Vladimir Chistyukhin, the Bank of Russia’s First Deputy Governor, declared at the St. Petersburg International Legal Forum in late June that Russian economy would face nothing short of „death” if the problem wasn’t resolved soon.

Maybe all these complications exist only because Putin has concentrated all his efforts on building a war machine focused on conquering Ukraine, and Russia’s military economy is contrarily thriving? Nothing of the sort.

In a May 2024 interview with RBC, Sergey Chemezov, Putin’s most powerful military oligarch and the CEO of Rostec, a major industrial conglomerate that is Russia’s biggest weapons producer, conceded that the situation in the Russian arms industry was quite dismal.

Some highlights from Chemezov’s interview: military producers endure near‑zero profitability (2,28% on average), and „we won’t last long“ (this is a direct quote) if this doesn’t change; 25% of transactions are made with non‑cash payments; military producers can’t borrow money at the credit market because of the Central Bank’s prohibitive interest rates unless the loan rates are heavily subsidized by the state, for which there are currently no funds available.

Maybe things are better in the army than in the arms industry? Well, you’ve probably guessed already, but in case you haven’t, here’s a couple of revealing quotes from the top‑ranking generals who told the truth about the state of the Russian military.

The first was General Shamanov, former commander of the Russian Airborne Forces and, before that, of the federal forces during the Chechen war in the mid‑1990s, now Deputy Chairman of the State Duma Committee for the Development of Civil Society, Issues of Public and Religious Associations.

Some highlights from Chemezov’s interview: military producers endure near‑zero profitability (2,28% on average), and „we won’t last long” (this is a direct quote) if this doesn’t change; 25% of transactions are made with non‑cash payments; military producers can’t borrow money at the credit market because of the Central Bank’s prohibitive interest rates unless the loan rates are heavily subsidized by the state, for which there are currently no funds available.

Maybe things are better in the army than in the arms industry? Well, you’ve probably guessed already, but in case you haven’t, here’s a couple of revealing quotes from the top‑ranking generals who told the truth about the state of the Russian military.

The first was General Shamanov, former commander of the Russian Airborne Forces and, before that, of the federal forces during the Chechen war in the mid‑1990s, now Deputy Chairman of the State Duma Committee for the Development of Civil Society, Issues of Public and Religious Associations.

In mid‑June, speaking from the State Duma podium, Shamanov denounced the supply system of the Russian armed forces as totally dysfunctional, with the army effectively „operating like a guerrilla unit“:

In mid‑June, speaking from the State Duma podium, Shamanov denounced the supply system of the Russian armed forces as totally dysfunctional, with the army effectively „operating like a guerrilla unit”:

“[The soldiers are] clothing themselves with their own money, at the expense of their relatives, because the quality of the uniform that is delivered and distributed doesn’t even deserve any assessment.”

“[The soldiers are] clothing themselves with their own money, at the expense of their relatives, because the quality of the uniform that is delivered and distributed doesn’t even deserve any assessment.”

Shamanov was followed by Sergei Stepashin, former Prime Minister of Russia and, before that, Director of the Federal Counterintelligence Service, the predecessor of the FSB.

At the St. Petersburg International Legal Forum in late June, Stepashin went as far as to say that “our military servicemen have turned to beggars” and that “of the salaries we gave them, half is spent on uniforms, on everything else the state should provide them with. Soldiers and officers go on vacation at their own expense.”

Shamanov was followed by Sergei Stepashin, former Prime Minister of Russia and, before that, Director of the Federal Counterintelligence Service, the predecessor of the FSB.

At the St. Petersburg International Legal Forum in late June, Stepashin went as far as to say that “our military servicemen have turned to beggars” and that “of the salaries we gave them, half is spent on uniforms, on everything else the state should provide them with. Soldiers and officers go on vacation at their own expense.”

The evidence of total disorder in the Russian army’s supply system corroborated by Mr. Shamanov and Mr. Stepashin is compellingly supported by data from the front lines.

Against this background, purchasing power parity of military service pay is rapidly shrinking due to inflation beating all the government’s expectations and wage indexation envisaged by the budget.

Would this picture still look good to many Western journalists and experts who describe the situation in Russia as solid as ever and claim that its economy is weathering the sanctions while the Kremlin is succeeding at having the society on a war footing?

Judging by the words of the Russian officials themselves and by the statistics, the said situation appears to be much worse than many Russia optimists in the West seem to imagine.

Vulnerabilities of Putin’s system are profound and rapidly progressing — with no remedy in sight. We’ve got to stop congratulating Putin on how greatly he is coping with the Western pressure — he is not — and focus instead on his deficiencies and their multiplication in order to make him lose the war in Ukraine before long.

The evidence of total disorder in the Russian army’s supply system corroborated by Mr. Shamanov and Mr. Stepashin is compellingly supported by data from the front lines.

Against this background, purchasing power parity of military service pay is rapidly shrinking due to inflation beating all the government’s expectations and wage indexation envisaged by the budget.

Would this picture still look good to many Western journalists and experts who describe the situation in Russia as solid as ever and claim that its economy is weathering the sanctions while the Kremlin is succeeding at having the society on a war footing?

Judging by the words of the Russian officials themselves and by the statistics, the said situation appears to be much worse than many Russia optimists in the West seem to imagine.

Vulnerabilities of Putin’s system are profound and rapidly progressing — with no remedy in sight. We’ve got to stop congratulating Putin on how greatly he is coping with the Western pressure — he is not — and focus instead on his deficiencies and their multiplication in order to make him lose the war in Ukraine before long.

Czar Broadcasts Panic

By Vladimir Milov

August 06, 2024

Report

Report More Uncertainty Follows as the Central Bank Yields to Pressure

By Vladimir Milov

January 13, 2025

Report

Report Between inflation and stagflation, lobbyists versus bankers, and the need for sanctions control

By Vladimir Milov

November 20, 2024

Czar Broadcasts Panic

By Vladimir Milov

August 06, 2024

Report

Report More Uncertainty Follows as the Central Bank Yields to Pressure

By Vladimir Milov

January 13, 2025

Report

Report Between inflation and stagflation, lobbyists versus bankers, and the need for sanctions control

By Vladimir Milov

November 20, 2024