Russian Economy's “Unholy Trinity”

Recession, Inflation, Budgetary Crisis

By Vladimir Milov January 29, 2026

Recession, Inflation, Budgetary Crisis

By Vladimir Milov January 29, 2026

Free Russia Foundation continues its series of briefs on the real status of the Russian economy beyond the headlines. Previous reports can be found online here.

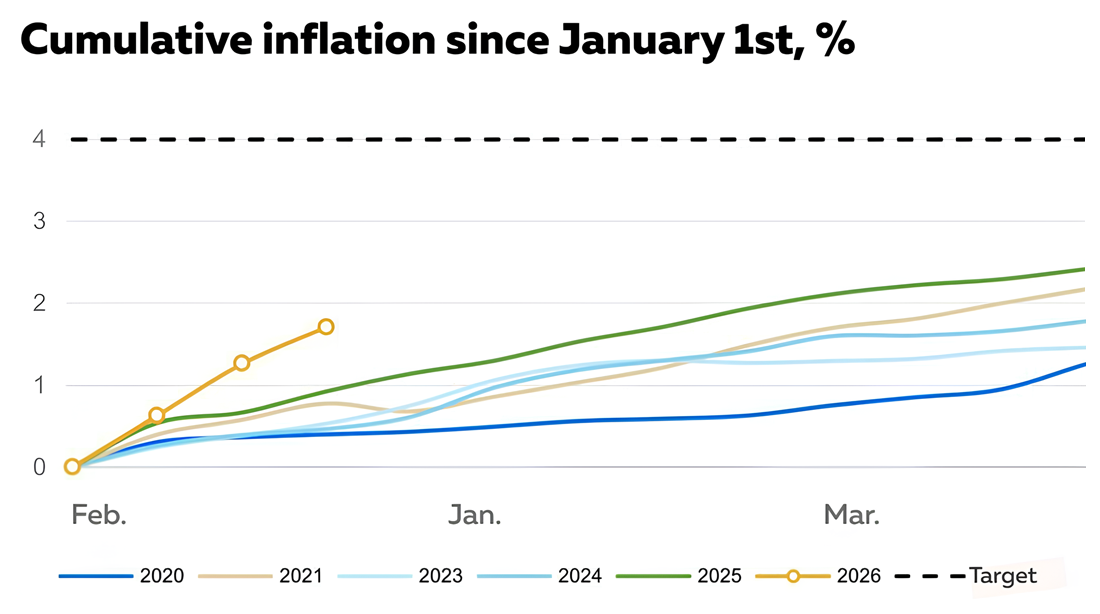

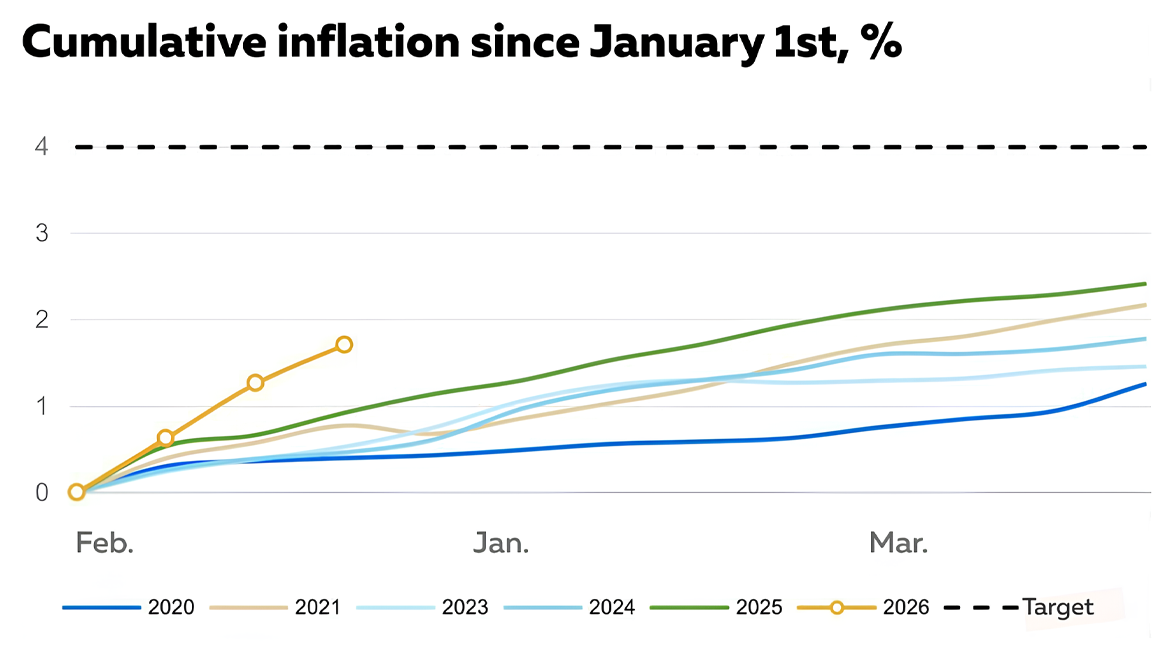

The beginning of 2026 has been marred by severely negative statistics and grim predictions for the Russian economy. First, in early January, inflation was much worse than previously expected – 1.72% after the first 19 days of January, the highest rate in the past five years, as opposed to 1.23% during the entire month of January the previous year. Inflation in January 2025 exceeded the highest monthly level since Q4 2024, when the Central Bank rushed to raise the key interest rate to 21% in a desperate effort to stop it, making it the highest monthly rate of inflation since March 2022.

The beginning of 2026 has been marred by severely negative statistics and grim predictions for the Russian economy. First, in early January, inflation was much worse than previously expected – 1.72% after the first 19 days of January, the highest rate in the past five years, as opposed to 1.23% during the entire month of January the previous year. Inflation in January 2025 exceeded the highest monthly level since Q4 2024, when the Central Bank rushed to raise the key interest rate to 21% in a desperate effort to stop it, making it the highest monthly rate of inflation since March 2022.

The January inflation data undermines all previous rhetoric about “Central Bank policy effectively taming inflation,” and calls into question further key interest rate cuts. This is a vital factor, as potential interest rate cuts were seen by many as the only remaining lifeline for the Russian economy. That possibility is now slipping out of sight.

Secondly, the Russian Ministry of Finance published the full data on the 2025 federal budget, with the deficit reaching 2.6% of GDP, or RUR 5.7 trillion. While 2.6% of GDP may not seem catastrophic to a Western observer, for Russia it is, because the country is unable to borrow at viable rates and the state's financial reserves are depleted. This leaves the issuance of state OFZ bonds, purchased by banks receiving repo financing from the Central Bank, as the only remaining mechanism for covering the deficit—a process that further fuels inflationary pressure.

The deficit will likely widen further, as Russia will not be able to maintain its budget revenues at currently planned levels. In December 2025, the average Urals oil price, as officially announced by the Russian government for taxation purposes, was just $39 per barrel, compared to $59 per barrel envisaged by the approved 2026 federal budget.

In December 2025, federal budget oil and gas revenues contracted by 43% compared to December 2024. As of mid‑January, heavy discounts for Russian exported crude oil to international benchmark prices ($25 and above) persisted. Given excess supply in the global oil market, resulting in depressed prices, Russia will most likely be unable to approach its $59 per barrel oil budgetary target in 2026. In addition, Russia is severely under‑collecting its domestic tax revenue due to a sharp cooling of the economy (see below for more detail).

Making the situation even worse, Russia's much‑celebrated GDP growth of 2023–2024 has vanished, and 2026 began with open discussion of the country slipping into recession.

The January inflation data undermines all previous rhetoric about “Central Bank policy effectively taming inflation,” and calls into question further key interest rate cuts. This is a vital factor, as potential interest rate cuts were seen by many as the only remaining lifeline for the Russian economy. That possibility is now slipping out of sight.

Secondly, the Russian Ministry of Finance published the full data on the 2025 federal budget, with the deficit reaching 2.6% of GDP, or RUR 5.7 trillion. While 2.6% of GDP may not seem catastrophic to a Western observer, for Russia it is, because the country is unable to borrow at viable rates and the state's financial reserves are depleted. This leaves the issuance of state OFZ bonds, purchased by banks receiving repo financing from the Central Bank, as the only remaining mechanism for covering the deficit—a process that further fuels inflationary pressure.

The deficit will likely widen further, as Russia will not be able to maintain its budget revenues at currently planned levels. In December 2025, the average Urals oil price, as officially announced by the Russian government for taxation purposes, was just $39 per barrel, compared to $59 per barrel envisaged by the approved 2026 federal budget.

In December 2025, federal budget oil and gas revenues contracted by 43% compared to December 2024. As of mid‑January, heavy discounts for Russian exported crude oil to international benchmark prices ($25 and above) persisted. Given excess supply in the global oil market, resulting in depressed prices, Russia will most likely be unable to approach its $59 per barrel oil budgetary target in 2026. In addition, Russia is severely under‑collecting its domestic tax revenue due to a sharp cooling of the economy (see below for more detail).

Making the situation even worse, Russia's much‑celebrated GDP growth of 2023–2024 has vanished, and 2026 began with open discussion of the country slipping into recession.

While the first data on economic performance in December 2025 will become available in early February 2026, the latest available indicators suggest that GDP growth in November 2025 has plunged to 0.1% — down from 4.3% in 2024. In October of last year, the Russian Central Bank lowered its GDP forecast for Q4 2025, allowing the possibility of a contraction. Fresh forecasts for early 2026 are considerably worse.

In early January 2026, Dmitry Belousov, director of the leading macroeconomic center employed by the Russian Government (Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short‑Term Forecasting, known under the Russian abbreviation CMAKP), and also the brother of Russia's current Minister of Defense Andrey Belousov (the actual founder of the center), acknowledged in two interviews with Russian regional media outlets—Ura.ru from Ekaterinburg and Business Online from Kazan—which are worth reading to understand the current picture of the Russian economy. Belousov acknowledges, among other things, that the possibility of recession in 2026 is very real.

While the first data on economic performance in December 2025 will become available in early February 2026, the latest available indicators suggest that GDP growth in November 2025 has plunged to 0.1% — down from 4.3% in 2024. In October of last year, the Russian Central Bank lowered its GDP forecast for Q4 2025, allowing the possibility of a contraction. Fresh forecasts for early 2026 are considerably worse.

In early January 2026, Dmitry Belousov, director of the leading macroeconomic center employed by the Russian Government (Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short‑Term Forecasting, known under the Russian abbreviation CMAKP), and also the brother of Russia's current Minister of Defense Andrey Belousov (the actual founder of the center), acknowledged in two interviews with Russian regional media outlets—Ura.ru from Ekaterinburg and Business Online from Kazan—which are worth reading to understand the current picture of the Russian economy. Belousov acknowledges, among other things, that the possibility of recession in 2026 is very real.

“Could economic growth turn negative? Yes, if investment declines and trade turnover, at the very least, stops growing.”

Dmitry Belousov

Director, Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short‑Term Forecasting, brother of Russia's Minister of Defense Andrey Belousov

“Could economic growth turn negative? Yes, if investment declines and trade turnover, at the very least, stops growing.”

Dmitry Belousov

Director, Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short‑Term Forecasting, brother of Russia's Minister of Defense Andrey Belousov

The assumptions about an upcoming recession are supported by a notable contraction of fixed investment: in Q3 2025, they have contracted by 3.1% on an annual basis, the first contraction since the 2020 COVID crisis. Investment contraction is an early indicator of GDP decline.

Dmitry Belousov also shared how he is on high alert about the current investment crisis:

The assumptions about an upcoming recession are supported by a notable contraction of fixed investment: in Q3 2025, they have contracted by 3.1% on an annual basis, the first contraction since the 2020 COVID crisis. Investment contraction is an early indicator of GDP decline.

Dmitry Belousov also shared how he is on high alert about the current investment crisis:

“We're in a very difficult investment situation. We warned that investment growth was at risk due to the combination of high interest rates, a strong ruble, which is hitting exporters' incomes, and low commodity prices, which could collectively depress investment, both borrowed and equity. Indeed, seasonally adjusted investment fell in the second and third quarters. … We're on a fairly problematic trend that we'll now have to reverse. This is the most serious problem, because in an attempt to contain inflation, we've curbed economic activity. We've delivered the heaviest blow to the investment perimeter.”

Dmitry Belousov

Director, Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short‑Term Forecasting

“We're in a very difficult investment situation. We warned that investment growth was at risk due to the combination of high interest rates, a strong ruble, which is hitting exporters' incomes, and low commodity prices, which could collectively depress investment, both borrowed and equity. Indeed, seasonally adjusted investment fell in the second and third quarters. … We're on a fairly problematic trend that we'll now have to reverse. This is the most serious problem, because in an attempt to contain inflation, we've curbed economic activity. We've delivered the heaviest blow to the investment perimeter.”

Dmitry Belousov

Director, Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short‑Term Forecasting

A deep investment crisis is confirmed by Russia's top bankers—Sberbank and VTB, which together control over 50% of total assets of Russia's banking system. In a recent interview, VTB's First Deputy CEO Dmitry Pyanov said there have been few applications for private sector investments.

A deep investment crisis is confirmed by Russia's top bankers—Sberbank and VTB, which together control over 50% of total assets of Russia's banking system. In a recent interview, VTB's First Deputy CEO Dmitry Pyanov said there have been few applications for private sector investments.

“Are there new investment projects emerging or demand for investment lending? Very few of those. You can count those coming from private sector on the fingers of one hand. There are some in the state‑owned sector; private entrepreneurs, on the contrary, are reducing their investments.”

Dmitry Pyanov,

First Deputy CEO, VTB Bank

“Are there new investment projects emerging or demand for investment lending? Very few of those. You can count those coming from private sector on the fingers of one hand. There are some in the state‑owned sector; private entrepreneurs, on the contrary, are reducing their investments.”

Dmitry Pyanov,

First Deputy CEO, VTB Bank

Earlier in 2025, Sberbank CEO German Gref admitted that in the first half of 2025, Russia's largest bank hadn’t provided financing to a single new investment project, and only older investments continued to be financed.

In addition to Russia's “uninvestable” business climate, which is another story beyond the scope of this report, three major factors contribute to a sharp decline in fixed investment:

Earlier in 2025, Sberbank CEO German Gref admitted that in the first half of 2025, Russia's largest bank hadn’t provided financing to a single new investment project, and only older investments continued to be financed.

In addition to Russia's “uninvestable” business climate, which is another story beyond the scope of this report, three major factors contribute to a sharp decline in fixed investment:

In the words of Alexandr Shokhin, head of the Russian Industrialists and Entrepreneurs Union, the country's largest big business association, current interest rates are beyond rates of return for nearly all of Russia's businesses, and to reignite economic activity in Russia' single‑digit interest rates are required:

In the words of Alexandr Shokhin, head of the Russian Industrialists and Entrepreneurs Union, the country's largest big business association, current interest rates are beyond rates of return for nearly all of Russia's businesses, and to reignite economic activity in Russia' single‑digit interest rates are required:

“There's a threshold for interest rate sensitivity for businesses. It starts somewhere around 12%. At rates above 15%, profitability is virtually nonexistent, with rare exceptions, not even across industries, but even for individual businesses. Therefore, of course, we'd like to see the key rate reach a single‑digit figure by the end of the year, meaning below 10%.”

Alexandr Shokhin

Head of the Russian Industrialists and Entrepreneurs Union

“There's a threshold for interest rate sensitivity for businesses. It starts somewhere around 12%. At rates above 15%, profitability is virtually nonexistent, with rare exceptions, not even across industries, but even for individual businesses. Therefore, of course, we'd like to see the key rate reach a single‑digit figure by the end of the year, meaning below 10%.”

Alexandr Shokhin

Head of the Russian Industrialists and Entrepreneurs Union

Earlier, Sberbank CEO German Gref stated that, according to his bank's estimates, the revival of business activity in Russia may only begin when the key interest rate is at 12% or below — which is probably an optimistic assumption. However, given current inflation trends, the Central Bank's key interest rate is not expected to reach 12% any time soon.

It is worth noting that, at the level of the Central Bank's key interest rate of 16%, the actual loan rates for most businesses stand well above 20%. Because banks offer loans at higher rates than the Central Bank key interest rate (currently, the average interest margin for Russian banks is 4–5%), in reality, it will require a 5% Central Bank key interest rate to make single‑digit bank loan rates available for entrepreneurs. But that prospect is not visible at the horizon.

The Central Bank's average key interest rate forecast for 2026 is currently 13–15%, and hopes for improvement of the situation are sharply fading, given the inflation trends of early January. Many analysts already predict that the Central Bank will at least pause lowering the key interest rate at its meeting in February.

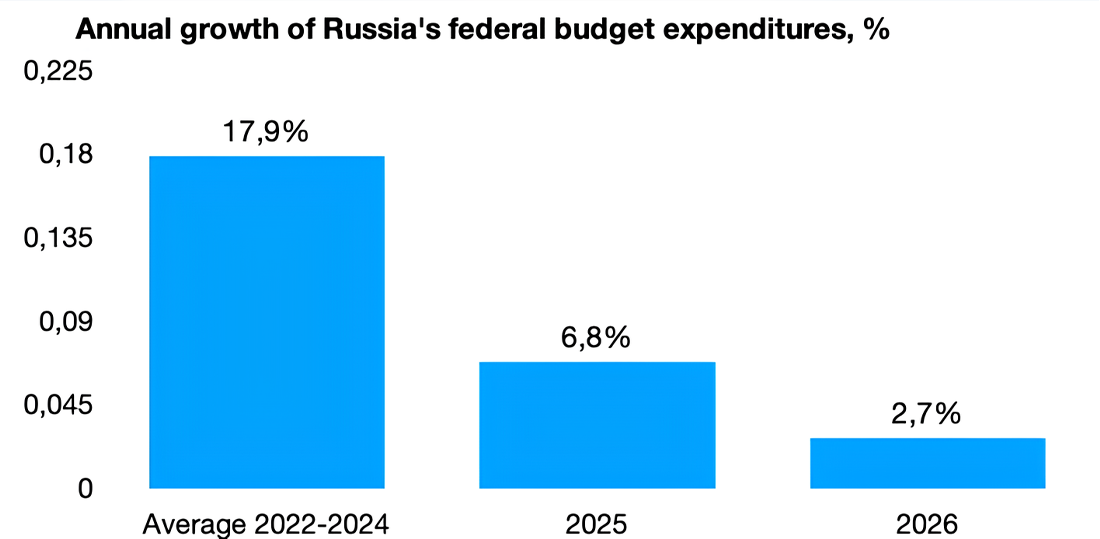

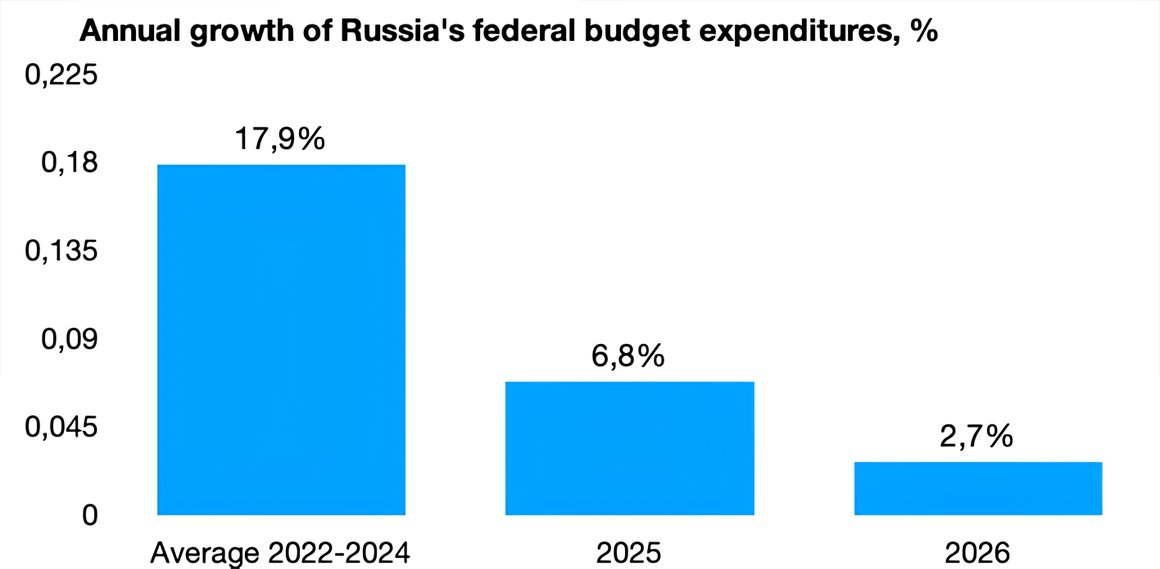

The situation is exacerbated by an ongoing budget crisis, which has led to a de‑facto freeze of government expenditure growth. The fiscal stimulus of 2022–2024 is effectively over, which doesn't offer hope to businesses that more investment aid is coming from the government.

Earlier, Sberbank CEO German Gref stated that, according to his bank's estimates, the revival of business activity in Russia may only begin when the key interest rate is at 12% or below — which is probably an optimistic assumption. However, given current inflation trends, the Central Bank's key interest rate is not expected to reach 12% any time soon.

It is worth noting that, at the level of the Central Bank's key interest rate of 16%, the actual loan rates for most businesses stand well above 20%. Because banks offer loans at higher rates than the Central Bank key interest rate (currently, the average interest margin for Russian banks is 4–5%), in reality, it will require a 5% Central Bank key interest rate to make single‑digit bank loan rates available for entrepreneurs. But that prospect is not visible at the horizon.

The Central Bank's average key interest rate forecast for 2026 is currently 13–15%, and hopes for improvement of the situation are sharply fading, given the inflation trends of early January. Many analysts already predict that the Central Bank will at least pause lowering the key interest rate at its meeting in February.

The situation is exacerbated by an ongoing budget crisis, which has led to a de‑facto freeze of government expenditure growth. The fiscal stimulus of 2022–2024 is effectively over, which doesn't offer hope to businesses that more investment aid is coming from the government.

In our recent publication “Russia's Budget Crisis, Explained”, we have explained Russia's ongoing budget crisis in detail and what it means for the war in Ukraine”.

For the first time since the beginning of the full‑scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russian authorities have stopped pretending that budget difficulties will be over after a couple of years of “structural transformation” of the economy, and now admit that high budget deficits will persist at least through 2026–2028, according to the newly adopted three‑year federal budget. Prior to the current period of high budget deficits from 2022–2028, the last uninterrupted seven‑year streak of high budget deficits recorded in Russia was from 1992–1999.

According to final federal budget figures for 2025 provided by the Russian Ministry of Finance, the deficit in 2025 amounted to 2.6% of GDP (RUR 5.7 trillion, or over $70 billion), five times higher than initially planned a year ago. On top of that, the aggregated deficit of Russian regional budgets exceeds 1% of GDP with only 2 out of 83 internationally recognized Russian regions having balanced budgets in 2025.

The 2025 federal budget demonstrated the key pains that the Russian government is facing under the pressure of Western sanctions:

In our recent publication “Russia's Budget Crisis, Explained”, we have explained Russia's ongoing budget crisis in detail and what it means for the war in Ukraine”.

For the first time since the beginning of the full‑scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russian authorities have stopped pretending that budget difficulties will be over after a couple of years of “structural transformation” of the economy, and now admit that high budget deficits will persist at least through 2026–2028, according to the newly adopted three‑year federal budget. Prior to the current period of high budget deficits from 2022–2028, the last uninterrupted seven‑year streak of high budget deficits recorded in Russia was from 1992–1999.

According to final federal budget figures for 2025 provided by the Russian Ministry of Finance, the deficit in 2025 amounted to 2.6% of GDP (RUR 5.7 trillion, or over $70 billion), five times higher than initially planned a year ago. On top of that, the aggregated deficit of Russian regional budgets exceeds 1% of GDP with only 2 out of 83 internationally recognized Russian regions having balanced budgets in 2025.

The 2025 federal budget demonstrated the key pains that the Russian government is facing under the pressure of Western sanctions:

The budget situation will become significantly worse due to the persistent effects of Western sanctions against Russian oil and gas exports. Russian oil export prices are currently below $40 per barrel, whereas the budget for 2026 was planned with the assumption of an average annual export oil price of $59 per barrel — clearly, Russia will not be able to meet that target. The Russian Ministry of Finance has already issued a warning in early January 2026 that a sharp increase in the federal budget deficit is expected in the first months of 2026.

While most commentators single out sanctions against the Russian oil and gas industry imposed by the Donald Trump administration – specifically, sanctions against two of Russia's biggest oil producers, Rosneft and Lukoil, imposed in October 2025 — it is important to note that oil sanctions imposed by the European Union also had a significant effect. Discounts for Russian crude bought by Asian customers began to widen long before sanctions were imposed by the Trump administration, having been adopted as the EU's 18th package of sanctions against Russia in July 2025.

A recent Kommersant article, for instance, discusses in detail the significant increase in costs (resulting in a corresponding drop in tax revenues for the Russian budget) for Russian oil companies due to the EU ban on petroleum products produced from crude oil of Russian origin taking effect.

Russia's rainy day cash fund, the National Wealth Fund (NWF), is practically exhausted and no longer available for financing the budget deficit. On January 1, 2026, NWF's liquidity portion consisted of only RUR 4 trillion, or 2% of GDP (just over $50 billion), and the government decided not to use it further, preserving it for future shocks. During the discussions on the federal budget in the State Duma, Finance Minister Anton Siluanov admitted that there's barely anything left in the NWF:

The budget situation will become significantly worse due to the persistent effects of Western sanctions against Russian oil and gas exports. Russian oil export prices are currently below $40 per barrel, whereas the budget for 2026 was planned with the assumption of an average annual export oil price of $59 per barrel — clearly, Russia will not be able to meet that target. The Russian Ministry of Finance has already issued a warning in early January 2026 that a sharp increase in the federal budget deficit is expected in the first months of 2026.

While most commentators single out sanctions against the Russian oil and gas industry imposed by the Donald Trump administration – specifically, sanctions against two of Russia's biggest oil producers, Rosneft and Lukoil, imposed in October 2025 — it is important to note that oil sanctions imposed by the European Union also had a significant effect. Discounts for Russian crude bought by Asian customers began to widen long before sanctions were imposed by the Trump administration, having been adopted as the EU's 18th package of sanctions against Russia in July 2025.

A recent Kommersant article, for instance, discusses in detail the significant increase in costs (resulting in a corresponding drop in tax revenues for the Russian budget) for Russian oil companies due to the EU ban on petroleum products produced from crude oil of Russian origin taking effect.

Russia's rainy day cash fund, the National Wealth Fund (NWF), is practically exhausted and no longer available for financing the budget deficit. On January 1, 2026, NWF's liquidity portion consisted of only RUR 4 trillion, or 2% of GDP (just over $50 billion), and the government decided not to use it further, preserving it for future shocks. During the discussions on the federal budget in the State Duma, Finance Minister Anton Siluanov admitted that there's barely anything left in the NWF:

“We don’t have a very large National Welfare Fund left, just about 4 trillion, of which only 3 trillion [1.5% of GDP] are unencumbered.”

Anton Siluanov

Minister of Finance of Russia

“We don’t have a very large National Welfare Fund left, just about 4 trillion, of which only 3 trillion [1.5% of GDP] are unencumbered.”

Anton Siluanov

Minister of Finance of Russia

Given the scarcity of revenue, the Russian government was forced to de‑facto freeze further federal expenditure growth to at least partially balance the state's finances. As an example, the average growth in federal budget expenditures from 2022–2024 was 17.9%, but in 2025 slowed to just 6.8%, and is planned to be trimmed to just 2.7% in 2026.

In the words of Finance Minister Anton Siluanov, the “budget stimulus can't be endless”.

Given the scarcity of revenue, the Russian government was forced to de‑facto freeze further federal expenditure growth to at least partially balance the state's finances. As an example, the average growth in federal budget expenditures from 2022–2024 was 17.9%, but in 2025 slowed to just 6.8%, and is planned to be trimmed to just 2.7% in 2026.

In the words of Finance Minister Anton Siluanov, the “budget stimulus can't be endless”.

“Budget stimulus can't be endless, otherwise there will be an imbalance in finances.”

Anton Siluanov

Minister of Finance of Russia

“Budget stimulus can't be endless, otherwise there will be an imbalance in finances.”

Anton Siluanov

Minister of Finance of Russia

The abrupt end of Russia's economic growth of 2023–2024 is directly related to shrinking fiscal stimulus. While some analysts in the West were busy praising the “resilience” of the Russian economy against Western sanctions, the real explanation was very simple: there was no organic “resilience” involved, just a massive injection of state financial aid to the economy through depletion of financial reserves accumulated before the full‑scale invasion of Ukraine. Once the reserves were spent, the “resilience miracle” also quickly ended.

To cover the budget deficit, the government opted for a second major tax increase in a year — from January 1st, 2025, the corporate profit tax rate was raised from 20% to 25%, and now, from January 1, 2026, the VAT rate was raised from 20% to 22%. Tax increases reduce investments and greatly contribute to economic slowdown. As outlined above, the downtrend in investment and growth in 2025 was visibly exacerbated by tax hikes.

The abrupt end of Russia's economic growth of 2023–2024 is directly related to shrinking fiscal stimulus. While some analysts in the West were busy praising the “resilience” of the Russian economy against Western sanctions, the real explanation was very simple: there was no organic “resilience” involved, just a massive injection of state financial aid to the economy through depletion of financial reserves accumulated before the full‑scale invasion of Ukraine. Once the reserves were spent, the “resilience miracle” also quickly ended.

To cover the budget deficit, the government opted for a second major tax increase in a year — from January 1st, 2025, the corporate profit tax rate was raised from 20% to 25%, and now, from January 1, 2026, the VAT rate was raised from 20% to 22%. Tax increases reduce investments and greatly contribute to economic slowdown. As outlined above, the downtrend in investment and growth in 2025 was visibly exacerbated by tax hikes.

Dwindling fiscal capabilities of the Russian government inevitably affect Russia's ability to finance the war in Ukraine. While financial constraints won't prevent Russia from producing enough missiles, gliding bombs and drones to continue air bombardments of Ukraine, Russia's ability to amass a strike force for another large‑scale offensive on Ukraine, let alone achieving decisive victory in the war, has been diminished by financial difficulties.

The fiscal tightening and budget expenditure freeze described above have affected the Russian military as well. Military expenditures expected for 2026–2028, as per officially published materials, are also capped at a level of RUR 13 trillion (just over $160 billion) per year — although that's an indicative figure not easily verifiable as the overall freeze of budget expenditures will unavoidably affect military spending and reduce room to maneuver.

As described by Defense Minister Andrey Belousov during his report at the Ministry's expanded Board meeting in December in the presence of Vladimir Putin, in order to be able to finance the continuation of the war in Ukraine, the Ministry was forced to cut all other expenditures, unrelated to the actual combat operations in Ukraine, by as much as 0.5% of GDP in 2025:

Dwindling fiscal capabilities of the Russian government inevitably affect Russia's ability to finance the war in Ukraine. While financial constraints won't prevent Russia from producing enough missiles, gliding bombs and drones to continue air bombardments of Ukraine, Russia's ability to amass a strike force for another large‑scale offensive on Ukraine, let alone achieving decisive victory in the war, has been diminished by financial difficulties.

The fiscal tightening and budget expenditure freeze described above have affected the Russian military as well. Military expenditures expected for 2026–2028, as per officially published materials, are also capped at a level of RUR 13 trillion (just over $160 billion) per year — although that's an indicative figure not easily verifiable as the overall freeze of budget expenditures will unavoidably affect military spending and reduce room to maneuver.

As described by Defense Minister Andrey Belousov during his report at the Ministry's expanded Board meeting in December in the presence of Vladimir Putin, in order to be able to finance the continuation of the war in Ukraine, the Ministry was forced to cut all other expenditures, unrelated to the actual combat operations in Ukraine, by as much as 0.5% of GDP in 2025:

“Tough austerity measures were applied to expenditures indirectly related to combat operations. Some expenditures were postponed, while others were cut. This made it possible to reduce the overall amount of such expenditures, as a share of GDP, from 2.7% in 2024 to 2.2 % in 2025.”

Andrey Belousov

Minister of Defense of Russia

“Tough austerity measures were applied to expenditures indirectly related to combat operations. Some expenditures were postponed, while others were cut. This made it possible to reduce the overall amount of such expenditures, as a share of GDP, from 2.7% in 2024 to 2.2 % in 2025.”

Andrey Belousov

Minister of Defense of Russia

An austere military budget negatively affects the solvency of the military industrial complex. In a recent interview, the CEO of the Rostec conglomerate (Russia's largest arms producer, supplying around 80% of weapons to the battlefield in Ukraine), Sergey Chemezov, admitted that most military enterprises operate at near‑zero or even negative profitability:

An austere military budget negatively affects the solvency of the military industrial complex. In a recent interview, the CEO of the Rostec conglomerate (Russia's largest arms producer, supplying around 80% of weapons to the battlefield in Ukraine), Sergey Chemezov, admitted that most military enterprises operate at near‑zero or even negative profitability:

“The profitability of military production remains low, and in some places it's zero, if not negative. This means we don't have much of our own funds for development.”

Sergey Chemezov

CEO, Rostec

“The profitability of military production remains low, and in some places it's zero, if not negative. This means we don't have much of our own funds for development.”

Sergey Chemezov

CEO, Rostec

PSB Bank, the Russian military industry’s specialized bank which serves as a backbone, was subject to additional capital injection by the state twice throughout 2025 — for a total amount of about $750 million. This reflects mounting financial difficulties at military enterprises – the main clients of PSB — and a growing share of nonperforming loans. Non‑payments generated by the state‑financed enterprises, including military factories, are quickly becoming one of the major problems in the economy.

In the 3rd quarter of 2025, according to a quarterly survey by the Russian Industrialists and Entrepreneurs Union, non‑payments were indicated by large Russian businesses as the Number One current problem impairing business activity.

At the same time, tensions and blame trading between the military sector and other segments of government and big business continue to grow against the background of mounting economic difficulties. Heavy military spending that doesn't generate any further positive multipliers for the economy is being openly blamed as the reason for Russia’s current economic problems as expressed by VTB Bank CEO Andrey Kostin in 2025 at the Central Bank's Financial Congress:

PSB Bank, the Russian military industry’s specialized bank which serves as a backbone, was subject to additional capital injection by the state twice throughout 2025 — for a total amount of about $750 million. This reflects mounting financial difficulties at military enterprises – the main clients of PSB — and a growing share of nonperforming loans. Non‑payments generated by the state‑financed enterprises, including military factories, are quickly becoming one of the major problems in the economy.

In the 3rd quarter of 2025, according to a quarterly survey by the Russian Industrialists and Entrepreneurs Union, non‑payments were indicated by large Russian businesses as the Number One current problem impairing business activity.

At the same time, tensions and blame trading between the military sector and other segments of government and big business continue to grow against the background of mounting economic difficulties. Heavy military spending that doesn't generate any further positive multipliers for the economy is being openly blamed as the reason for Russia’s current economic problems as expressed by VTB Bank CEO Andrey Kostin in 2025 at the Central Bank's Financial Congress:

“We're always very timid when talking about the causes of our current economic problems… high military spending is the cause of inflation. These high military expenditures … don't even lead to manufacturing of products that end up on the market. These products are flown off somewhere, so supply doesn't increase, while costs rise. And the second reason [behind current economic problems], of course, which can't be ignored, is the enormous number of sanctions.”

Andrey Kostin

CEO, VTB Bank

“We're always very timid when talking about the causes of our current economic problems… high military spending is the cause of inflation. These high military expenditures … don't even lead to manufacturing of products that end up on the market. These products are flown off somewhere, so supply doesn't increase, while costs rise. And the second reason [behind current economic problems], of course, which can't be ignored, is the enormous number of sanctions.”

Andrey Kostin

CEO, VTB Bank

There are no easy ways to solve Russia's persistent budget deficit problem. The Russian government tried major tax hikes in the past few years — but their potential seems to be largely exhausted, and they have clearly negatively contributed to profitability and investment activity of the Russian business sector, triggering stagnation, and, potentially, a coming recession in 2026. Importantly, tax hikes couldn’t fundamentally resolve the deficit problem as high budget deficits persist.

Common knowledge rests on the assumption that Russia will be able to get along with increased borrowing — also mentioning Russia's low government debt relative to GDP. However, borrowing cannot be considered a solution to the deficit problem for several reasons:

There are no easy ways to solve Russia's persistent budget deficit problem. The Russian government tried major tax hikes in the past few years — but their potential seems to be largely exhausted, and they have clearly negatively contributed to profitability and investment activity of the Russian business sector, triggering stagnation, and, potentially, a coming recession in 2026. Importantly, tax hikes couldn’t fundamentally resolve the deficit problem as high budget deficits persist.

Common knowledge rests on the assumption that Russia will be able to get along with increased borrowing — also mentioning Russia's low government debt relative to GDP. However, borrowing cannot be considered a solution to the deficit problem for several reasons:

Here's a quote from Finance Minister Anton Siluanov recognizing all these problems in one of the recent interviews:

Here's a quote from Finance Minister Anton Siluanov recognizing all these problems in one of the recent interviews:

“Firstly, our debt market capacity isn't as deep as those countries we like to cite, whose debt may even exceed 100% of GDP. We're currently focusing exclusively on domestic investors in our securities. There are no foreign investors. Second, our debt is expensive. We're currently borrowing at interest rates around 14%. If you look at the volume of interest expenses, they already account for around 8% of all expenditures. If we continue to increase debt, it will push out all other expenditures. We'll have less money left over for our priorities.”

Anton Siluanov

Minister of Finance of Russia

“Firstly, our debt market capacity isn't as deep as those countries we like to cite, whose debt may even exceed 100% of GDP. We're currently focusing exclusively on domestic investors in our securities. There are no foreign investors. Second, our debt is expensive. We're currently borrowing at interest rates around 14%. If you look at the volume of interest expenses, they already account for around 8% of all expenditures. If we continue to increase debt, it will push out all other expenditures. We'll have less money left over for our priorities.”

Anton Siluanov

Minister of Finance of Russia

It should be noted that Siluanov here directly disagrees with Putin, who keeps publicly insisting that the budget deficit “is not a problem,” because Russia has “low government debt and can borrow any time.” As happens too often, Putin is lying.

Data released by the Russian Ministry of Finance suggests that, at current high interest rates (government 10‑year OFZ bond yields are in the range of 14–15%), debt raised from the market is largely being offset by debt servicing payments. In 2026, debt servicing costs are supposed to be close to 10% of total budget expenditures. Borrowing will make more sense if interest rates go down significantly — but that doesn't seem to be happening any time soon.

In 2025, according to data released by the Russian Ministry of Finance, net receipts to the federal budget from the issuance of OFZ government bonds (RUR 2.3 trillion) made up only a third of the total amount of debt issued (RUR 6.8 trillion) — and another two thirds were paid back instead as principal debt and interest.

It should be noted that Siluanov here directly disagrees with Putin, who keeps publicly insisting that the budget deficit “is not a problem,” because Russia has “low government debt and can borrow any time.” As happens too often, Putin is lying.

Data released by the Russian Ministry of Finance suggests that, at current high interest rates (government 10‑year OFZ bond yields are in the range of 14–15%), debt raised from the market is largely being offset by debt servicing payments. In 2026, debt servicing costs are supposed to be close to 10% of total budget expenditures. Borrowing will make more sense if interest rates go down significantly — but that doesn't seem to be happening any time soon.

In 2025, according to data released by the Russian Ministry of Finance, net receipts to the federal budget from the issuance of OFZ government bonds (RUR 2.3 trillion) made up only a third of the total amount of debt issued (RUR 6.8 trillion) — and another two thirds were paid back instead as principal debt and interest.

Given limited demand for long‑term OFZ bonds at the Russian financial market (“limited debt market capacity,” as per Finance Minister Siluanov cited above), the Russian government increasingly resorts to the “repo‑to-OFZ” scheme of debt financing — effectively, monetary emission by the Central Bank masked under the disguise of providing banks with extra liquidity. Official data shows that “providing liquidity” to banks has grown exponentially along with the government's hunger for cash and increased borrowing through state OFZ bonds.

At the end of 2025, when the Russian Ministry of Finance announced a stark increase of planned OFZ borrowing limit for 2025 by over 40% (from initially planned RUR 4.8 trillion to the actual amount of RUR 6.8 trillion), the Central Bank had simultaneously greatly increased the amount of liquidity provided to banks at weekly repo auctions — from an average RUR 0,9 trillion per week in January‑October 2025 to RUR 2,2 trillion per week in November 2025 and over RUR 3 trillion per week in December 2025 and January 2026. This provided banks with the liquidity needed to buy additional government's OFZ bonds.

The repo auctions for banks keep rolling over on a weekly basis, with the overall amount of liquidity provided notably increasing over time — which means that banks, effectively, purchase government OFZ bonds with Central Bank money, not their own money. The return to a repo scheme was announced in late 2024 after a notable break, and, despite the Central Bank's earlier pledges to end it shortly, it keeps rolling over, and the amount of cash provided to banks keeps growing.

Given limited demand for long‑term OFZ bonds at the Russian financial market (“limited debt market capacity,” as per Finance Minister Siluanov cited above), the Russian government increasingly resorts to the “repo‑to-OFZ” scheme of debt financing — effectively, monetary emission by the Central Bank masked under the disguise of providing banks with extra liquidity. Official data shows that “providing liquidity” to banks has grown exponentially along with the government's hunger for cash and increased borrowing through state OFZ bonds.

At the end of 2025, when the Russian Ministry of Finance announced a stark increase of planned OFZ borrowing limit for 2025 by over 40% (from initially planned RUR 4.8 trillion to the actual amount of RUR 6.8 trillion), the Central Bank had simultaneously greatly increased the amount of liquidity provided to banks at weekly repo auctions — from an average RUR 0,9 trillion per week in January‑October 2025 to RUR 2,2 trillion per week in November 2025 and over RUR 3 trillion per week in December 2025 and January 2026. This provided banks with the liquidity needed to buy additional government's OFZ bonds.

The repo auctions for banks keep rolling over on a weekly basis, with the overall amount of liquidity provided notably increasing over time — which means that banks, effectively, purchase government OFZ bonds with Central Bank money, not their own money. The return to a repo scheme was announced in late 2024 after a notable break, and, despite the Central Bank's earlier pledges to end it shortly, it keeps rolling over, and the amount of cash provided to banks keeps growing.

Buying government OFZ bonds with the Central Bank's money is no different from a traditional monetary emission scheme, when the Central Bank simply issues credit to the government to finance the budget deficit — only that this time it is disguised by using banks as intermediaries.

The “repo‑to-OFZ” scheme is highly pro‑inflationary — and it’s hard to separate the January inflation spike from the additional liquidity injection into the economy months before. It generally doesn't relieve the Ministry of Finance from the burden of high debt cost — borrowing rates are still high. But the necessary liquidity is easily found — from the Central Bank resorting to a “money printing machine.” The resulting effects on inflation and interest rates are extremely negative, which is why Central Bank governor Elvira Nabiullina openly advocates for tax hikes as a better way to finance the budget deficit, despite their adverse effects on profitability and business activity.

But Russian authorities don't have anywhere else to go except further using the “repo‑to-OFZ” scheme to finance the deficit. International financial markets are inaccessible, the potential for tax hikes is all but expired, and raising debt in the domestic market has its limits, as explained above. So “print baby print” mode will most likely continue — having the most negative impact on inflation, as is already visible in January 2026.

Buying government OFZ bonds with the Central Bank's money is no different from a traditional monetary emission scheme, when the Central Bank simply issues credit to the government to finance the budget deficit — only that this time it is disguised by using banks as intermediaries.

The “repo‑to-OFZ” scheme is highly pro‑inflationary — and it’s hard to separate the January inflation spike from the additional liquidity injection into the economy months before. It generally doesn't relieve the Ministry of Finance from the burden of high debt cost — borrowing rates are still high. But the necessary liquidity is easily found — from the Central Bank resorting to a “money printing machine.” The resulting effects on inflation and interest rates are extremely negative, which is why Central Bank governor Elvira Nabiullina openly advocates for tax hikes as a better way to finance the budget deficit, despite their adverse effects on profitability and business activity.

But Russian authorities don't have anywhere else to go except further using the “repo‑to-OFZ” scheme to finance the deficit. International financial markets are inaccessible, the potential for tax hikes is all but expired, and raising debt in the domestic market has its limits, as explained above. So “print baby print” mode will most likely continue — having the most negative impact on inflation, as is already visible in January 2026.

A widespread misconception in many of the Western reviews of the current state of the Russian economy is that Russia, despite all its economic woes, has “managed to tame inflation” through the Central Bank's tight monetary policies. This is not true and shall be disproved.

First, Russia's inflation is still high — even as reported, around 6%. It’s still the second highest in the G20 after Turkey, and significantly higher than the Central Bank's 4% target. Second, there is a significant degree of statistical manipulation involved in reporting Russia's inflation. Here are the two most visible examples of 2025:

A widespread misconception in many of the Western reviews of the current state of the Russian economy is that Russia, despite all its economic woes, has “managed to tame inflation” through the Central Bank's tight monetary policies. This is not true and shall be disproved.

First, Russia's inflation is still high — even as reported, around 6%. It’s still the second highest in the G20 after Turkey, and significantly higher than the Central Bank's 4% target. Second, there is a significant degree of statistical manipulation involved in reporting Russia's inflation. Here are the two most visible examples of 2025:

Just these two manipulations alone put the annual inflation of 2025 likely well above 6%, instead of 5.6% as officially reported. Not to mention that, in January 2026, inflation was reported to be 1.72% just after the first 19 days of January — making it the highest monthly inflation since March 2022.

Explanations associated with a VAT increase don't hold water because in January 2019, when the VAT rate was also raised by 2 percentage points, January inflation didn't exceed 1%. Also, the largest price growth between January 1–19, 2026, was recorded in vegetables (including 28.5% for cucumbers and 17.3% for tomatoes), which are exempt from a VAT increase, and are subject to only 10% VAT taxation as “socially sensitive goods.”

The January 2026 price spike brought annualized inflation back to 6.5%, with the CMAKP macroeconomic center predicting it to be as high as 7% by the end of the month.

Some temporary cooling of inflation in the first weeks of December was explained by the Central Bank itself as massive warehouse stock sales by businesses which wanted to avoid their goods being taxed with the 22% increased VAT after January 1. The Central Bank warned back then that “this may result in higher price growth in early January”.

Third, the breakdown of inflation in December 2025 suggests that deflation trends were highly localized to just a few goods, and these temporary deflation trends are largely over. In December 2025, deflation (-8.8% in annualized terms compared to December 2024) was recorded only in fruits and vegetables — but this trend was more than offset in January 2026, and prices for fruits and vegetables are rising again.

Moderate price growth in non‑food products in December (3.0%) reflects price contraction in the first half of 2025, when prices were depressed by higher interest rates, and consumers refrained from new loan borrowing to finance purchases of durable goods — although demand for durables, and the corresponding price growth, was back up in the second half of 2025.

The annualized inflation from December 2025 for services and food products excluding fruits and vegetables, was quite high at 9.3% and 7.4%, respectively.

None of these figures suggest that the Russian Central Bank has “managed to tame” inflation.

Fourth, indirect data provided by the Central Bank itself suggests that the official inflation numbers are significantly underreported. According to the Russian Central Bank, inflation expectations of the Russian population and “observed inflation” (inflation actually reported by the population as per the Central Bank's surveys) remain at 13–15%, while the key interest rate has remained at 16% and above for over two and a half years. Russia is an unusual example of such a protracted negative gap between reported and observed inflation; and an obvious explanation for this is that official inflation remains seriously underreported.

Given the above data, it is probably safe to say that claims of Russia's “success in taming inflation” are quite premature. Russia still faces high inflation.

Just these two manipulations alone put the annual inflation of 2025 likely well above 6%, instead of 5.6% as officially reported. Not to mention that, in January 2026, inflation was reported to be 1.72% just after the first 19 days of January — making it the highest monthly inflation since March 2022.

Explanations associated with a VAT increase don't hold water because in January 2019, when the VAT rate was also raised by 2 percentage points, January inflation didn't exceed 1%. Also, the largest price growth between January 1–19, 2026, was recorded in vegetables (including 28.5% for cucumbers and 17.3% for tomatoes), which are exempt from a VAT increase, and are subject to only 10% VAT taxation as “socially sensitive goods.”

The January 2026 price spike brought annualized inflation back to 6.5%, with the CMAKP macroeconomic center predicting it to be as high as 7% by the end of the month.

Some temporary cooling of inflation in the first weeks of December was explained by the Central Bank itself as massive warehouse stock sales by businesses which wanted to avoid their goods being taxed with the 22% increased VAT after January 1. The Central Bank warned back then that “this may result in higher price growth in early January”.

Third, the breakdown of inflation in December 2025 suggests that deflation trends were highly localized to just a few goods, and these temporary deflation trends are largely over. In December 2025, deflation (-8.8% in annualized terms compared to December 2024) was recorded only in fruits and vegetables — but this trend was more than offset in January 2026, and prices for fruits and vegetables are rising again.

Moderate price growth in non‑food products in December (3.0%) reflects price contraction in the first half of 2025, when prices were depressed by higher interest rates, and consumers refrained from new loan borrowing to finance purchases of durable goods — although demand for durables, and the corresponding price growth, was back up in the second half of 2025.

The annualized inflation from December 2025 for services and food products excluding fruits and vegetables, was quite high at 9.3% and 7.4%, respectively.

None of these figures suggest that the Russian Central Bank has “managed to tame” inflation.

Fourth, indirect data provided by the Central Bank itself suggests that the official inflation numbers are significantly underreported. According to the Russian Central Bank, inflation expectations of the Russian population and “observed inflation” (inflation actually reported by the population as per the Central Bank's surveys) remain at 13–15%, while the key interest rate has remained at 16% and above for over two and a half years. Russia is an unusual example of such a protracted negative gap between reported and observed inflation; and an obvious explanation for this is that official inflation remains seriously underreported.

Given the above data, it is probably safe to say that claims of Russia's “success in taming inflation” are quite premature. Russia still faces high inflation.

The Russian Central Bank finds itself in a very difficult position.

On one hand, January 2026 inflation trends leave the bankers with no other reasonable choice but to keep or even increase the key interest rate at their Board meeting on February 13th. During its December discussion on the key interest rate, the Central Bank noted that pro‑inflationary risks still prevail, which require a protracted, tight monetary policy. January 2026 inflation will exceed all previous expectations, which goes beyond any reasonable explanations related to VAT increase, as outlined above.

On the other hand, economic and investment cooling trends are so worrisome, and recipes for economic revival are so narrowly focused on expectations of further Central Bank rate cuts (as said above, fiscal stimulus is off the table), that pausing interest rate cuts will mean dashing the business and government hopes to re‑ignite economic activity in 2026. As a result, negative sentiment may overtake the business community to such an extent that Russia will face large‑scale shutdowns of projects and entire businesses, which kept rolling so far expecting interest rate cuts on the horizon.

No matter what the Russian Central Bank does, it will not make the situation any better. In reality, bank loans make up only 10–15% of financing for fixed investment — around 60% comes from companies' own profits, and another 15–20% are from state budget funds. The Russian banking system doesn't provide much of the long‑term financing needed for the investment process in most industries. Margins in most of the sectors of the Russian economy are so low that the Central Bank's key interest rate — would need to be below 5% (assumed that the actual bank loan rates will be several percentage points higher) to somehow notably revive economic activity.

Previous experience of lowering the Central Bank key interest rate to 7–8% in 2018–2019 and to as low as 4% during the 2020 Covid pandemic doesn't offer evidence that relatively lower interest rates significantly boost economic activity. Therefore, the massive focus on the Central Bank key interest rate as a tool of economic revival is probably a mass public delusion in Russia, at a time when it is prohibited to talk about war and sanctions as main causes of current economic problems.

Therefore, chances that accelerated interest rate cuts will revive economic activity against the background of an array of mounting other economic challenges are slim. But it will surely boost inflation further. So will the exacerbating budget deficit problems – increasing the deficit (due to shortfall of oil and gas export revenues and under‑collection of domestic taxes due to cooling of the Russian economy) is a major pro‑inflationary factor.

However, if the Central Bank pauses or reverses interest rate cuts, it will do little to bring inflation under control because the key pro‑inflationary factors, like the budget deficit in the first place, will persist, but the effects on the economy may be devastating. Not because the interest rate is so important for business and investment, but because hopes for interest rate cuts are the only silver lining that exists for entrepreneurs who are struggling against the background of war, sanctions, tax hikes and all the negativity that currently dominates the Russian economic environment. A pause in interest rate cuts may serve as the last trigger for the massive shutdown of business activity in Russia.

The Russian Central Bank finds itself in a very difficult position.

On one hand, January 2026 inflation trends leave the bankers with no other reasonable choice but to keep or even increase the key interest rate at their Board meeting on February 13th. During its December discussion on the key interest rate, the Central Bank noted that pro‑inflationary risks still prevail, which require a protracted, tight monetary policy. January 2026 inflation will exceed all previous expectations, which goes beyond any reasonable explanations related to VAT increase, as outlined above.

On the other hand, economic and investment cooling trends are so worrisome, and recipes for economic revival are so narrowly focused on expectations of further Central Bank rate cuts (as said above, fiscal stimulus is off the table), that pausing interest rate cuts will mean dashing the business and government hopes to re‑ignite economic activity in 2026. As a result, negative sentiment may overtake the business community to such an extent that Russia will face large‑scale shutdowns of projects and entire businesses, which kept rolling so far expecting interest rate cuts on the horizon.

No matter what the Russian Central Bank does, it will not make the situation any better. In reality, bank loans make up only 10–15% of financing for fixed investment — around 60% comes from companies' own profits, and another 15–20% are from state budget funds. The Russian banking system doesn't provide much of the long‑term financing needed for the investment process in most industries. Margins in most of the sectors of the Russian economy are so low that the Central Bank's key interest rate — would need to be below 5% (assumed that the actual bank loan rates will be several percentage points higher) to somehow notably revive economic activity.

Previous experience of lowering the Central Bank key interest rate to 7–8% in 2018–2019 and to as low as 4% during the 2020 Covid pandemic doesn't offer evidence that relatively lower interest rates significantly boost economic activity. Therefore, the massive focus on the Central Bank key interest rate as a tool of economic revival is probably a mass public delusion in Russia, at a time when it is prohibited to talk about war and sanctions as main causes of current economic problems.

Therefore, chances that accelerated interest rate cuts will revive economic activity against the background of an array of mounting other economic challenges are slim. But it will surely boost inflation further. So will the exacerbating budget deficit problems – increasing the deficit (due to shortfall of oil and gas export revenues and under‑collection of domestic taxes due to cooling of the Russian economy) is a major pro‑inflationary factor.

However, if the Central Bank pauses or reverses interest rate cuts, it will do little to bring inflation under control because the key pro‑inflationary factors, like the budget deficit in the first place, will persist, but the effects on the economy may be devastating. Not because the interest rate is so important for business and investment, but because hopes for interest rate cuts are the only silver lining that exists for entrepreneurs who are struggling against the background of war, sanctions, tax hikes and all the negativity that currently dominates the Russian economic environment. A pause in interest rate cuts may serve as the last trigger for the massive shutdown of business activity in Russia.

The Russian economic situation has reached a breaking point in 2026, facing the “unholy trinity” of challenges:

The Russian economic situation has reached a breaking point in 2026, facing the “unholy trinity” of challenges:

If in 2025 the key word describing Russia's economic woes was “stagflation,” Russia is probably already past that point — in 2026, the country is arguably facing something far worse — an inflationary decline. Economic decline will likely be accompanied with high inflation, further exacerbating the downward spiral.

Attempts to revive the economy through monetary policy and means such as premature lowering of the key interest rate, pro‑inflationary financing of budget deficit through “repo‑to-OFZ” scheme will only make the inflationary challenges worse. There is no option for an economic “bazooka” – a massive injection of a fiscal stimulus as that option expired during 2022–2024. Yes, government debt is low, but Russia mostly can't borrow at reasonable terms, as explained above — so a debt option simply isn't working as a tool to assist the ailing economy.

It should be noted that all the difficulties described above are direct products of Western sanctions introduced from 2022 and before. Sanctions have cut Russia off from international investments, technology and financial markets. This has impaired the country's ability to revitalize its production sector, making sure that the “bounce‑back” economic growth of 2023–2024 remains temporary and is followed by a rapid slowdown. The production sector lagging behind demand is a key reason for persistent inflation, as correctly explained by the Russian Central Bank.

Sanctions exhausting Russia's state budget capabilities are the key factor why the government no longer has the fiscal capacity to offer more aid to the economy. Putin's “economic miracle” and “resilience” of 2022–2204 is predictably over. It will inevitably have an impact on Russia's ability to further wage war against Ukraine and threaten Europe’s security and democracy.

Free Russia Foundation will continue to provide updates on the Russian economic situation, its impact on the war in Ukraine, as well as other topics related to Russia — demography, status of the Russian military industries, scenarios for Putin's policies in the near future and how they are impacted by the worsening economic situation. The purpose of this report is to portray a realistic picture of the Russian economic difficulties in the beginning of 2026, clear of widespread prejudices and misconceptions.

If in 2025 the key word describing Russia's economic woes was “stagflation,” Russia is probably already past that point — in 2026, the country is arguably facing something far worse — an inflationary decline. Economic decline will likely be accompanied with high inflation, further exacerbating the downward spiral.

Attempts to revive the economy through monetary policy and means such as premature lowering of the key interest rate, pro‑inflationary financing of budget deficit through “repo‑to-OFZ” scheme will only make the inflationary challenges worse. There is no option for an economic “bazooka” – a massive injection of a fiscal stimulus as that option expired during 2022–2024. Yes, government debt is low, but Russia mostly can't borrow at reasonable terms, as explained above — so a debt option simply isn't working as a tool to assist the ailing economy.

It should be noted that all the difficulties described above are direct products of Western sanctions introduced from 2022 and before. Sanctions have cut Russia off from international investments, technology and financial markets. This has impaired the country's ability to revitalize its production sector, making sure that the “bounce‑back” economic growth of 2023–2024 remains temporary and is followed by a rapid slowdown. The production sector lagging behind demand is a key reason for persistent inflation, as correctly explained by the Russian Central Bank.

Sanctions exhausting Russia's state budget capabilities are the key factor why the government no longer has the fiscal capacity to offer more aid to the economy. Putin's “economic miracle” and “resilience” of 2022–2204 is predictably over. It will inevitably have an impact on Russia's ability to further wage war against Ukraine and threaten Europe’s security and democracy.

Free Russia Foundation will continue to provide updates on the Russian economic situation, its impact on the war in Ukraine, as well as other topics related to Russia — demography, status of the Russian military industries, scenarios for Putin's policies in the near future and how they are impacted by the worsening economic situation. The purpose of this report is to portray a realistic picture of the Russian economic difficulties in the beginning of 2026, clear of widespread prejudices and misconceptions.

And what it means for the war in Ukraine

By Vladimir Milov

November 04, 2025

Article

Article When the rhetoric of an “unlimited alliance” faces economic reality

By Vladimir Milov

October 15, 2025

Report

Report By Vladimir Milov

September 24, 2025

And what it means for the war in Ukraine

By Vladimir Milov

November 04, 2025

Article

Article When the rhetoric of an “unlimited alliance” faces economic reality

By Vladimir Milov

October 15, 2025

Report

Report By Vladimir Milov

September 24, 2025