Russia’s Budget Crisis, Explained

And what it means for the war in Ukraine

By Vladimir Milov November 04, 2025

And what it means for the war in Ukraine

By Vladimir Milov November 04, 2025

In early October 2025, the Russian government published a full version of Russia’s draft federal budget for 2026–2028, the country’s main financial document defining Putin’s policy priorities for the moment. While the figures provided by the draft budget shall be taken with a grain of salt, and will be subject to major revisions — the federal budget for the current year 2025, for instance, was already significantly revised three times in less than 12 months, with a projected deficit increasing from 0.5% to 2.6% of GDP (which is still not the final figure yet) — it nonetheless gives a good indication of where Russia currently stands economically, and what Putin’s policy intentions are at least in the short term. This paper provides a brief glance at the most important takeaways from the draft budget — and the situation for Putin — and Russia — doesn’t look too bright. Moreover, it will be fair to say that Russia has entered a full‑blown budget crisis, which is now recognized by the authorities: the budget for 2026–2028 admits that Russia faces seven consecutive years of high budget deficit, something unseen since 1999, amounting to no less than a full‑scale budget crisis.

Here are some of the most important points to be noted.

Here are some of the most important points to be noted.

To begin with, the government sharply revised downward its macroeconomic forecasts for 2025–2026. Previously, it was hoped that the Russian economy will be able to maintain much higher levels of economic growth throughout the next few years because of “structural transformation” of the economy (development of import substitution, re‑orientation toward economic cooperation with the Global South instead of the West).

However, this is no longer expected. The GDP growth is expected to be around 1% (the Russian Central Bank at its board meeting of October 2025 lowered the 2025 GDP growth forecast to 0.5–1.0%), sharply down from around 4% growth in 2023–2024, and from the previous forecast of 2.5–2.6% growth for 2025–2026.

The government also acknowledges a sharp decline in investment activity: forecast for fixed investment growth was also revised downward, and, for 2026, Russian authorities now predict investment contraction.

To begin with, the government sharply revised downward its macroeconomic forecasts for 2025–2026. Previously, it was hoped that the Russian economy will be able to maintain much higher levels of economic growth throughout the next few years because of “structural transformation” of the economy (development of import substitution, re‑orientation toward economic cooperation with the Global South instead of the West).

However, this is no longer expected. The GDP growth is expected to be around 1% (the Russian Central Bank at its board meeting of October 2025 lowered the 2025 GDP growth forecast to 0.5–1.0%), sharply down from around 4% growth in 2023–2024, and from the previous forecast of 2.5–2.6% growth for 2025–2026.

The government also acknowledges a sharp decline in investment activity: forecast for fixed investment growth was also revised downward, and, for 2026, Russian authorities now predict investment contraction.

| 2025 | 2026 | |

| GDP annual growth as projected at the end of 2024, % | 2.5 % | 2.6 % |

| Revised GDP annual growth projection as envisaged by the draft 2026–2028 federal budget, % | 1.0 % | 1.3 % |

| Fixed investment annual growth as projected at the end of 2024, % | 2.1 % | 3.0 % |

| Revised fixed investment annual growth projection as envisaged by the draft 2026–2028 federal budget, % change | 1.7 % | ‑0.5 % |

The actual numbers may turn out to be even worse, as the Russian government is slow to acknowledge the swift cooling of the Russian economy. Seasonally adjusted GDP growth already in August was reported to be 0.0%, and forward indicators of business activity show an accelerated slowdown (the overall economic dynamics were discussed in more detail in our recent paper; we’ll come back to this issue again soon).

Less growth means less tax and budget revenue: over 75% of the total revenues of the Russian federal budget are non‑oil and gas revenues (oil and gas revenues make only less than 25%). Contrary to widespread perception, the Russian budget depends much more on domestic tax revenue rather than oil and gas exports. So, accelerated economic contraction may lead to severe revenue shortages as opposed to current estimates. This issue is discussed in more detail below.

The actual numbers may turn out to be even worse, as the Russian government is slow to acknowledge the swift cooling of the Russian economy. Seasonally adjusted GDP growth already in August was reported to be 0.0%, and forward indicators of business activity show an accelerated slowdown (the overall economic dynamics were discussed in more detail in our recent paper; we’ll come back to this issue again soon).

Less growth means less tax and budget revenue: over 75% of the total revenues of the Russian federal budget are non‑oil and gas revenues (oil and gas revenues make only less than 25%). Contrary to widespread perception, the Russian budget depends much more on domestic tax revenue rather than oil and gas exports. So, accelerated economic contraction may lead to severe revenue shortages as opposed to current estimates. This issue is discussed in more detail below.

The main takeaway from the draft federal budget for 2026–2028 is that the Russian government no longer believes that budgetary problems will end sometime soon. In the previous years, the government wanted everyone to believe that high deficits are just for a couple of years, after which the situation will improve:

The main takeaway from the draft federal budget for 2026–2028 is that the Russian government no longer believes that budgetary problems will end sometime soon. In the previous years, the government wanted everyone to believe that high deficits are just for a couple of years, after which the situation will improve:

However, the budget deficit for the upcoming year was always seriously underestimated, as can be seen from the table 2 below.

However, the budget deficit for the upcoming year was always seriously underestimated, as can be seen from the table 2 below.

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

| Projection at the end of previous year (during budget’s adoption), % of GDP | 1.0 % | 2.0 % | 0.9 % | 0.5 % |

| Actual deficit, % of GDP | 2.1 % | 1.9 % | 1.7 % | 2.6 %* |

But this time, the remarkable change is that the Russian government even now admits that the deficit will remain much higher for the foreseeable future, as shown by the government’s three‑year planning horizon. The federal budget deficit for 2026 is now projected to be 1.6% of GDP, and for 2027–2028 — 1.2–1.3% of GDP. Also, the government has dropped the goal of keeping the deficit below 1% of GDP, which was officially pursued in 2024–2025, but never achieved in reality.

As table 2 shows, the Russian government’s deficit projections for 2024–2025 were badly beaten as the effects of Western sanctions were taking its toll. Since the beginning of the full‑scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russia generally couldn’t keep its budget deficit under control — it has always missed expectations, and was leaning toward 2% of GDP or higher.

Some Western readers may ask a question: so what? Many Western nations live for years with budget deficits of 1–2% GDP or even higher. However, the Russian situation is very different:

But this time, the remarkable change is that the Russian government even now admits that the deficit will remain much higher for the foreseeable future, as shown by the government’s three‑year planning horizon. The federal budget deficit for 2026 is now projected to be 1.6% of GDP, and for 2027–2028 — 1.2–1.3% of GDP. Also, the government has dropped the goal of keeping the deficit below 1% of GDP, which was officially pursued in 2024–2025, but never achieved in reality.

As table 2 shows, the Russian government’s deficit projections for 2024–2025 were badly beaten as the effects of Western sanctions were taking its toll. Since the beginning of the full‑scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russia generally couldn’t keep its budget deficit under control — it has always missed expectations, and was leaning toward 2% of GDP or higher.

Some Western readers may ask a question: so what? Many Western nations live for years with budget deficits of 1–2% GDP or even higher. However, the Russian situation is very different:

A significant portion of the Russian GDP is also military related, which on paper reports added value, but in reality, doesn’t generate any further value creation chain. As Andrey Kostin, chairman of Russia’s second biggest bank, VTB, recently said at the Central Bank’s Financial Congress,

A significant portion of the Russian GDP is also military related, which on paper reports added value, but in reality, doesn’t generate any further value creation chain. As Andrey Kostin, chairman of Russia’s second biggest bank, VTB, recently said at the Central Bank’s Financial Congress,

«high military expenditures don’t generate products that reach the market — they are just flying off somewhere. So, the money is spent, but supply doesn’t increase, while costs rise.“

«high military expenditures don’t generate products that reach the market — they are just flying off somewhere. So, the money is spent, but supply doesn’t increase, while costs rise.”

This is very much resemblant of the Soviet system, where high military expenditures distorted the GDP composition, and the effective “productive” GDP was much lower than the official numbers.

Therefore, the Russian federal budget deficit relative to the “productive” civilian GDP is in reality much higher than the official numbers of 1.5–2% of GDP.

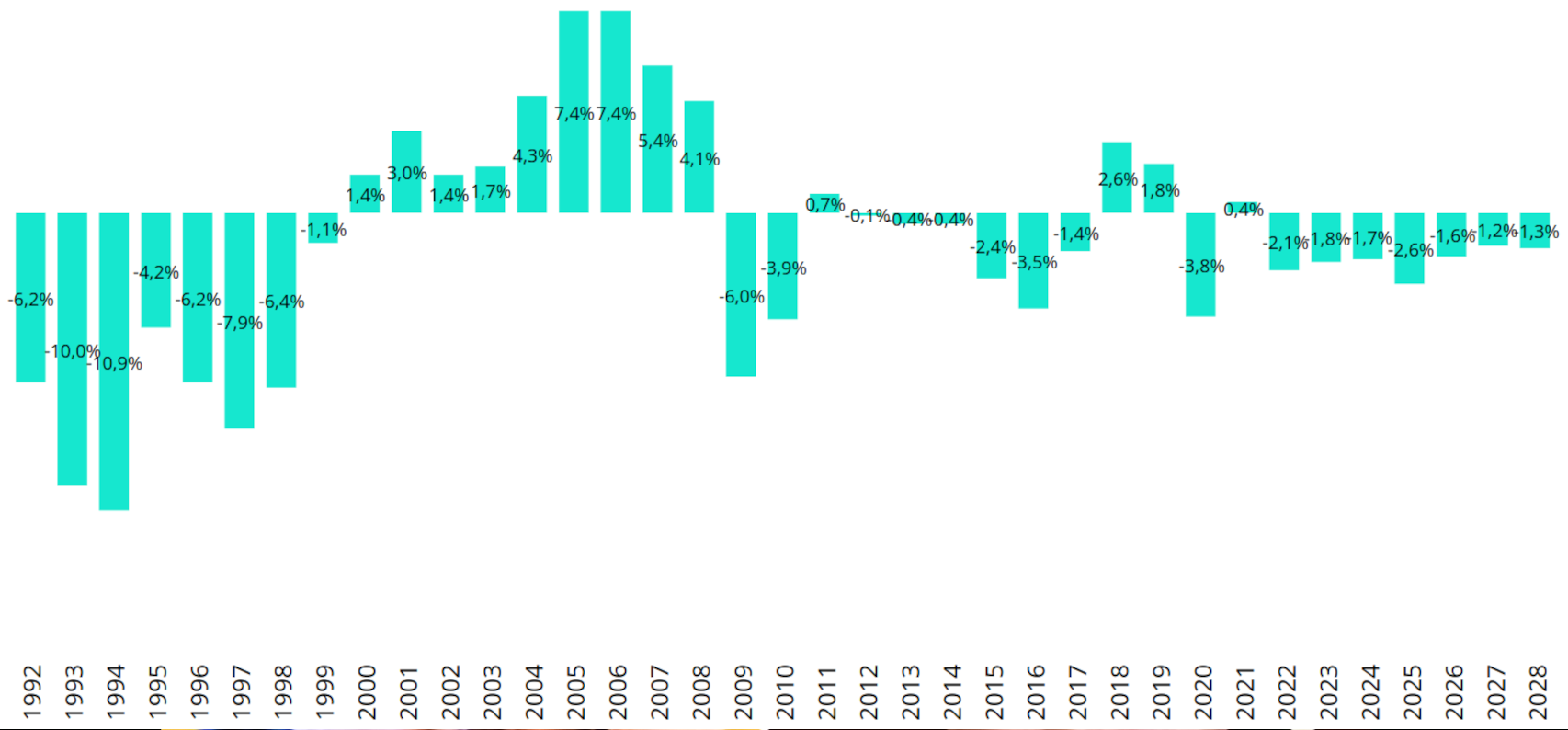

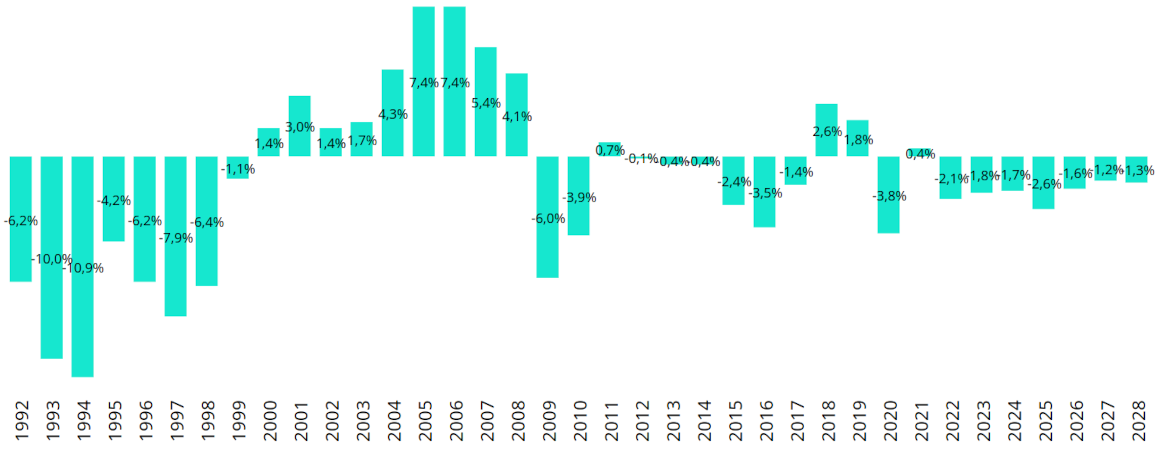

Russia hasn’t had seven consecutive years of high budget deficits since 1999. As can be seen from graph 1 below, since the beginning of Putin’s rule, Russia had three previous periods of budget deficits: 2009–2010 (in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis), 2012–2017 (continued echoes of the 2008 financial crisis followed by the 2014 sanctions and oil price collapse), and 2020 (covid). After each of the deficit crises, Russia managed to come out with a budget surplus plus some preserved financial reserves. This will be no longer the case now, as a balanced budget — let alone budget surpluses — are no longer seen on the government’s planning horizon, and financial reserves are nearly depleted (see more on that below).

This makes the situation very different — and in a lot of ways more menacing — than the 1990s. While in the first half of the 1990s, as can be seen from graph 1, Russia’s federal budget deficit reached as high as 6–11% of GDP, the situation was improving, and there was a visible way out of the woods — economic reforms, cooperation with the IMF, support from the Western governments. As explained above, the case is very different now. While the deficits are lower than those in the early 1990s as a share of GDP, the country seems to have entered a protracted period of inability to balance the government’s finances, with no end in sight.

This is very much resemblant of the Soviet system, where high military expenditures distorted the GDP composition, and the effective “productive” GDP was much lower than the official numbers.

Therefore, the Russian federal budget deficit relative to the “productive” civilian GDP is in reality much higher than the official numbers of 1.5–2% of GDP.

Russia hasn’t had seven consecutive years of high budget deficits since 1999. As can be seen from graph 1 below, since the beginning of Putin’s rule, Russia had three previous periods of budget deficits: 2009–2010 (in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis), 2012–2017 (continued echoes of the 2008 financial crisis followed by the 2014 sanctions and oil price collapse), and 2020 (covid). After each of the deficit crises, Russia managed to come out with a budget surplus plus some preserved financial reserves. This will be no longer the case now, as a balanced budget — let alone budget surpluses — are no longer seen on the government’s planning horizon, and financial reserves are nearly depleted (see more on that below).

This makes the situation very different — and in a lot of ways more menacing — than the 1990s. While in the first half of the 1990s, as can be seen from graph 1, Russia’s federal budget deficit reached as high as 6–11% of GDP, the situation was improving, and there was a visible way out of the woods — economic reforms, cooperation with the IMF, support from the Western governments. As explained above, the case is very different now. While the deficits are lower than those in the early 1990s as a share of GDP, the country seems to have entered a protracted period of inability to balance the government’s finances, with no end in sight.

As can be seen from graph 1 above, across the 20‑year time span from 2009–2028, Russia was no longer able to achieve notable and lasting budget surpluses. Since 2008, a budget surplus was recorded only for four years, and only two of them (2018 and 2019) demonstrated notable budget surpluses of 2–3% of GDP (in 2011 and 2021 the budget surplus was largely symbolic, only slightly above zero).

For most of the two decades since 2008, Russia had/is planning to have notable budget deficits. It’s worth noting that oil prices were not low during that period — the average oil price for 2009–2024 was $77 per barrel, and only in 2015–2016 and 2020 were average global oil prices in the range of $40–50 per barrel.

Persistent budget deficit is a fundamental consequence of several factors:

As can be seen from graph 1 above, across the 20‑year time span from 2009–2028, Russia was no longer able to achieve notable and lasting budget surpluses. Since 2008, a budget surplus was recorded only for four years, and only two of them (2018 and 2019) demonstrated notable budget surpluses of 2–3% of GDP (in 2011 and 2021 the budget surplus was largely symbolic, only slightly above zero).

For most of the two decades since 2008, Russia had/is planning to have notable budget deficits. It’s worth noting that oil prices were not low during that period — the average oil price for 2009–2024 was $77 per barrel, and only in 2015–2016 and 2020 were average global oil prices in the range of $40–50 per barrel.

Persistent budget deficit is a fundamental consequence of several factors:

With the Russian economy increasingly dependent on the state, growth more and more depended on government spending. As Kommersant notes analyzing the review of slowing investment activity across the Russian regions, investment activity remains positive “only in regions with a significant presence of companies from the defense industry and sectors that receive state support through import substitution and technological sovereignty programs.”

This increasing economic dependence of businesses from state aid — apart from growing military spending — greatly pushed up expenditures, which the government failed to keep under control.

With the Russian economy increasingly dependent on the state, growth more and more depended on government spending. As Kommersant notes analyzing the review of slowing investment activity across the Russian regions, investment activity remains positive “only in regions with a significant presence of companies from the defense industry and sectors that receive state support through import substitution and technological sovereignty programs.”

This increasing economic dependence of businesses from state aid — apart from growing military spending — greatly pushed up expenditures, which the government failed to keep under control.

The key headache for the war‑driven, internationally isolated and state‑dependent economy is the permanently growing state spending, which just can’t stop. The government needs to spend more for many reasons:

The key headache for the war‑driven, internationally isolated and state‑dependent economy is the permanently growing state spending, which just can’t stop. The government needs to spend more for many reasons:

As can be seen from table 3 below, the government wasn’t able to make good on its promises to keep the federal spending under control: in the end, federal budget expenditures turned out to be significantly higher as a share of GDP than initially planned. (Please bear in mind that the 2025 figures are not final and, as previous experience shows, are a significant underestimate — but still even they beat the initial spending plans.)

As can be seen from table 3 below, the government wasn’t able to make good on its promises to keep the federal spending under control: in the end, federal budget expenditures turned out to be significantly higher as a share of GDP than initially planned. (Please bear in mind that the 2025 figures are not final and, as previous experience shows, are a significant underestimate — but still even they beat the initial spending plans.)

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

| Projected federal budget expenditures at the time of budget adoption, % of GDP | 15.1 % | 16.5 % | 18.2 % | 19.1 % |

| Actual federal budget expenditures, % of GDP | 19.8 % | 18.3 % | 20.0 % | 19.7%* |

The government’s pledges to keep federal spending under control was already heavily criticized as unrealistic — for 2026–2028, it intends to keep the federal spending just slightly above 18% of GDP, much lower than the actual share of GDP in 2024–2025 (around 20% of GDP). But this is hardly possible, given the recent trends and the increasing, not receding, economy’s dependence on state aid. Billionaire Oleg Deripaska has publicly blasted the presented draft budget as totally out of touch with reality:

The government’s pledges to keep federal spending under control was already heavily criticized as unrealistic — for 2026–2028, it intends to keep the federal spending just slightly above 18% of GDP, much lower than the actual share of GDP in 2024–2025 (around 20% of GDP). But this is hardly possible, given the recent trends and the increasing, not receding, economy’s dependence on state aid. Billionaire Oleg Deripaska has publicly blasted the presented draft budget as totally out of touch with reality:

“I still want to see some realistic plans… I understand there’s no harm in dreaming, but why fool ourselves?”.

“I still want to see some realistic plans… I understand there’s no harm in dreaming, but why fool ourselves?”.

Bottom line: the deficit will be even higher in the remaining months of 2025 and the years 2026–2028, as the current trends and economic model suggest.

Bottom line: the deficit will be even higher in the remaining months of 2025 and the years 2026–2028, as the current trends and economic model suggest.

Russia’s federal revenue forecast is also built on too optimistic forecasts for oil and non‑oil revenues. Real revenues will most likely be much lower than the current estimates, further exacerbating the problem of budget deficits.

The assumed oil price taken for calculating the budget’s oil revenue is $58 per barrel on average for 2025, $59 for 2026, $61 for 2027, and $65 for 2028. This looks too optimistic, bearing in mind the current debate about a significant glut at the international oil market as reported by the International Energy Agency and others, and on the background of the fact that, in mid‑October, the export price for Russian Urals crude fell below the new oil price cap set by the EU — below $47.6 per barrel.

Russian officials admit the excessively optimistic nature of budget oil price projections: in mid‑October, during the debate on the draft federal budget in the State Duma, Alexander Zhukov, First Deputy Speaker of the State Duma and the most prominent figure in the ruling “United Russia” State Duma faction on financial and economic policy, noted that the oil price assumptions of the draft federal budget for 2026–2028 are “too optimistic,“ and that discounts for Russian Urals export crude relative to Brent oil prices «may turn out to be higher than expected.”

Non‑oil revenues of the federal budget — which, contrary to widespread opinion, account for the bulk of Russia’s revenues (78% of Russia’s projected total federal budget revenue for 2026, while oil and gas revenues account only for slightly above 20%) — will most likely be depressed by the rapid cooling of the economy, with economic growth and tax collection falling behind the government’s forecasts.

Approximately 70% of the non‑oil revenues of the federal budget come from two main taxes — VAT and corporate profit tax. It is already visible in 2025 that the slowdown of economic activity seriously undermines the government’s plans for tax collection — as shown in table 4 below. The situation in the remaining period of 2025 and 2026 is likely to be even worse, given the rapid economic slowdown.

Russia’s federal revenue forecast is also built on too optimistic forecasts for oil and non‑oil revenues. Real revenues will most likely be much lower than the current estimates, further exacerbating the problem of budget deficits.

The assumed oil price taken for calculating the budget’s oil revenue is $58 per barrel on average for 2025, $59 for 2026, $61 for 2027, and $65 for 2028. This looks too optimistic, bearing in mind the current debate about a significant glut at the international oil market as reported by the International Energy Agency and others, and on the background of the fact that, in mid‑October, the export price for Russian Urals crude fell below the new oil price cap set by the EU — below $47.6 per barrel.

Russian officials admit the excessively optimistic nature of budget oil price projections: in mid‑October, during the debate on the draft federal budget in the State Duma, Alexander Zhukov, First Deputy Speaker of the State Duma and the most prominent figure in the ruling “United Russia” State Duma faction on financial and economic policy, noted that the oil price assumptions of the draft federal budget for 2026–2028 are “too optimistic,” and that discounts for Russian Urals export crude relative to Brent oil prices «may turn out to be higher than expected.”

Non‑oil revenues of the federal budget — which, contrary to widespread opinion, account for the bulk of Russia’s revenues (78% of Russia’s projected total federal budget revenue for 2026, while oil and gas revenues account only for slightly above 20%) — will most likely be depressed by the rapid cooling of the economy, with economic growth and tax collection falling behind the government’s forecasts.

Approximately 70% of the non‑oil revenues of the federal budget come from two main taxes — VAT and corporate profit tax. It is already visible in 2025 that the slowdown of economic activity seriously undermines the government’s plans for tax collection — as shown in table 4 below. The situation in the remaining period of 2025 and 2026 is likely to be even worse, given the rapid economic slowdown.

| Planned for 2025 (as of end‑2024) | Actual (8 months of 2025) | |

| VAT collection growth, % vs. 2024 | +16.8% | +6.9% |

| Corporate profit tax collection, % vs. 2024 | +99.0% | +77.6% |

As can be seen from table 4, VAT collection growth this year was below 7%, as opposed to budget plans for nearly a 17% increase. Corporate profit tax revenues were expected to double this year, in large part due to an increase of the profit tax rate from 20% to 25% — but profit tax collection in reality grows much slower. It shall be noted that, after 8 months of 2025, total net corporate profits of Russian companies fell by over 8% year‑on-year, and after the first half of 2025, Russian publicly traded companies' interim dividends halved — demonstrating that crisis takes a major toll on corporate profits.

This means that, if the tax collection efforts will underperform as now vis‑a-vis earlier plans, the federal budget will be short of RUR 1.7 trillion (over $20 billion) of planned domestic revenue (0.8% of GDP). A similar picture can be expected in 2026. Table 5 below shows how much government overestimated budget revenues for 2025 a year ago, when the federal budget for 2025 was adopted.

As can be seen from table 4, VAT collection growth this year was below 7%, as opposed to budget plans for nearly a 17% increase. Corporate profit tax revenues were expected to double this year, in large part due to an increase of the profit tax rate from 20% to 25% — but profit tax collection in reality grows much slower. It shall be noted that, after 8 months of 2025, total net corporate profits of Russian companies fell by over 8% year‑on-year, and after the first half of 2025, Russian publicly traded companies' interim dividends halved — demonstrating that crisis takes a major toll on corporate profits.

This means that, if the tax collection efforts will underperform as now vis‑a-vis earlier plans, the federal budget will be short of RUR 1.7 trillion (over $20 billion) of planned domestic revenue (0.8% of GDP). A similar picture can be expected in 2026. Table 5 below shows how much government overestimated budget revenues for 2025 a year ago, when the federal budget for 2025 was adopted.

| Actual revenues (estimate for full year 2025 as of October 2025) vs. initially planned revenues (at end‑2024 during the budget adoption), % | |

| Total federal budget revenues | ‑9.3 % |

| Oil & gas revenues | ‑20.9 % |

| Non‑oil & gas revenues | ‑4.9 % |

Starting in 2024, Russia stopped reporting the actual figures of annual military spending, showing instead only planned figures for the next years. This makes the military spending figures provided as part of supplementary materials for 2025 and 2026–2028 federal budgets non‑verifiable.

Before the draft federal budget for 2025 was presented in the fall of 2024, budgetary projections always included aggregated estimates of total actual military spending for the ending year — e.g., in the supplementary materials for 2024 budget, the actual military spending figure for 2023 was provided two years ago. However, beginning a year ago, the Russian government no longer reports actual figures of military spending — only the projected figures for the next years. This bears little value, as planned figures normally don’t correspond to reality and are frequently revised.

For 2026–2028, the Russian government projects more or less flat military spending figures, around the same as the planned figure for 2025 (table 6). If taken at face value, these figures would mean that Russia is intending to cap its military spending at the 2025 level for the next 3 years in ruble terms, and to reduce them relative to GDP. However, in reality, it is not verifiable directly and should not be taken at face value.

Starting in 2024, Russia stopped reporting the actual figures of annual military spending, showing instead only planned figures for the next years. This makes the military spending figures provided as part of supplementary materials for 2025 and 2026–2028 federal budgets non‑verifiable.

Before the draft federal budget for 2025 was presented in the fall of 2024, budgetary projections always included aggregated estimates of total actual military spending for the ending year — e.g., in the supplementary materials for 2024 budget, the actual military spending figure for 2023 was provided two years ago. However, beginning a year ago, the Russian government no longer reports actual figures of military spending — only the projected figures for the next years. This bears little value, as planned figures normally don’t correspond to reality and are frequently revised.

For 2026–2028, the Russian government projects more or less flat military spending figures, around the same as the planned figure for 2025 (table 6). If taken at face value, these figures would mean that Russia is intending to cap its military spending at the 2025 level for the next 3 years in ruble terms, and to reduce them relative to GDP. However, in reality, it is not verifiable directly and should not be taken at face value.

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | |

| RUR trillion | 3.4 | 4.7 | 6.4 | 10.7 | 13.5 | 12.9 | 13.6 | 13.1 |

| % of GDP | 2.5 % | 3.0 % | 3.6 % | 5.3 % | 6,2 % | 5.5 % | 5.5 % | 4.7 % |

What is true though is that ballooning military expenditures are a key driver of Russia’s budget crisis — as publicly acknowledged recently by VTB Bank Chairman Andrey Kostin (see above) and the Ministry of Finance is motivated to hide their actual growth in order not to scare the macroeconomic community. Military spending growth exceeding all expectations was a major factor behind total budget expenditures becoming out of control in 2022–2025 as shown in table 3 above.

What is true though is that ballooning military expenditures are a key driver of Russia’s budget crisis — as publicly acknowledged recently by VTB Bank Chairman Andrey Kostin (see above) and the Ministry of Finance is motivated to hide their actual growth in order not to scare the macroeconomic community. Military spending growth exceeding all expectations was a major factor behind total budget expenditures becoming out of control in 2022–2025 as shown in table 3 above.

Due to Western sanctions, Russia has been effectively cut off from the international financial markets, and the government can’t borrow internationally. There were hopes that China would save Russia financially — but the Chinese government not only provided zero loans to the Russian budget and is clearly not intending to do so, but also blocked Russia’s plans to gain access to the Chinese financial market to be able to raise debt there. Since 2015, Russia touted plans to issue yuan‑denominated bonds to be able to borrow at the Chinese financial market, but these plans faced regulatory resistance from the Chinese government — after which they were dropped. In May 2025, Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov admitted that the plans to issue yuan‑denominated federal bonds have been dropped.

Domestic borrowing through the Ministry of Finance’s state bonds (OFZ) simply doesn’t work under current interest rates. At the moment, yields on 10‑year state OFZ bonds exceed 15%. With this high cost of debt servicing, net debt raised this year barely exceeded $4 billion, or 0.16% of GDP — a negligible amount.

While overall federal debt remains relatively low, the costs of its servicing is ballooning — in 2021 servicing costs made just 0,9% of GDP, they are planned to be close to 2% of GDP in 2026, or nearly 9% of overall federal spending in 2026 (twice as big a share as compared to 2021).

So, borrowing from the market is not an option to fill the deficit gap for the Russian government. unless inflation and interest rates are brought down significantly (which is not happening, as inflation recently picked up again with annualized inflation well above 8%). As a result, high interest payments offset the debt raised from the market by the Russian government.

Due to Western sanctions, Russia has been effectively cut off from the international financial markets, and the government can’t borrow internationally. There were hopes that China would save Russia financially — but the Chinese government not only provided zero loans to the Russian budget and is clearly not intending to do so, but also blocked Russia’s plans to gain access to the Chinese financial market to be able to raise debt there. Since 2015, Russia touted plans to issue yuan‑denominated bonds to be able to borrow at the Chinese financial market, but these plans faced regulatory resistance from the Chinese government — after which they were dropped. In May 2025, Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov admitted that the plans to issue yuan‑denominated federal bonds have been dropped.

Domestic borrowing through the Ministry of Finance’s state bonds (OFZ) simply doesn’t work under current interest rates. At the moment, yields on 10‑year state OFZ bonds exceed 15%. With this high cost of debt servicing, net debt raised this year barely exceeded $4 billion, or 0.16% of GDP — a negligible amount.

While overall federal debt remains relatively low, the costs of its servicing is ballooning — in 2021 servicing costs made just 0,9% of GDP, they are planned to be close to 2% of GDP in 2026, or nearly 9% of overall federal spending in 2026 (twice as big a share as compared to 2021).

So, borrowing from the market is not an option to fill the deficit gap for the Russian government. unless inflation and interest rates are brought down significantly (which is not happening, as inflation recently picked up again with annualized inflation well above 8%). As a result, high interest payments offset the debt raised from the market by the Russian government.

The government’s financial reserves are nearly fully depleted and should be disregarded as a significant potential source of filling the budget deficit gap. As of October 1, 2025, the liquidity part of the National Wealth Fund (NWF), the Russian government’s rainy day fund, held only RUR 4.2 trillion ($50 billion) of reserves, which won’t be sufficient to cover even the currently estimated budget deficit for 2025 — RUR 5.7 trillion. Remaining cash reserves, therefore, are about 30% less than the expected 2025 budget deficit alone (not to mention that this year’s actual budget deficit will most certainly be higher, or that the years 2026–2028 will also feature large budget deficits, as shown above).

There’s also a non‑liquidity part of the NWF, which is worth roughly RUR 9 trillion ($108 billion) on paper, but these are largely investments into shares and securities of state‑affiliated corporations and banks that are hardly immediately recoverable — it will be difficult for government to use them to finance current budget deficits (the issue was discussed in more detail in one of our recent reports).

The government’s financial reserves are nearly fully depleted and should be disregarded as a significant potential source of filling the budget deficit gap. As of October 1, 2025, the liquidity part of the National Wealth Fund (NWF), the Russian government’s rainy day fund, held only RUR 4.2 trillion ($50 billion) of reserves, which won’t be sufficient to cover even the currently estimated budget deficit for 2025 — RUR 5.7 trillion. Remaining cash reserves, therefore, are about 30% less than the expected 2025 budget deficit alone (not to mention that this year’s actual budget deficit will most certainly be higher, or that the years 2026–2028 will also feature large budget deficits, as shown above).

There’s also a non‑liquidity part of the NWF, which is worth roughly RUR 9 trillion ($108 billion) on paper, but these are largely investments into shares and securities of state‑affiliated corporations and banks that are hardly immediately recoverable — it will be difficult for government to use them to finance current budget deficits (the issue was discussed in more detail in one of our recent reports).

Putin’s government is diving fully into trying to solve the country’s budgetary problems, but it doesn’t help much. The corporate profit tax was raised from 20% to 25% on January 1, 2025, and now, a VAT increase from 20% to 22% is planned to take effect on January 1, 2026. But it all won’t help much. The additional corporate profit tax collection due to the tax rate increase in 2025 is supposed to generate an additional RUR 1.7 trillion ($21 billion) of revenue for the budget, which is just a fraction of the 2025 deficit planned so far — RUR 5.7 billion ($71 billion).

It’s the same story with the VAT increase in 2026: it is also supposed to generate an additional RUR 1.7 trillion of revenue, which will not solve even half of the 2026 budget deficit problem (budget deficit for 2026 is expected to be RUR 3.8 trillion even after the VAT increase).

Tax hikes don’t help to raise revenue sufficient to solve the deficit problem — but they definitely contribute to the economic slowdown. This was admitted even by pro‑government economists like the Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short‑Term Forecasting founded by current Minister of Defense Andrey Belousov and chaired today by his brother Dmitry — which suggested last year that the profit tax hike from 2025 will have negative contribution to fixed investment dynamics of 0.4%. Now, officials admit that the VAT increase in January 2026 will contribute to higher inflation, and through that, will negatively impact interest rates and growth.

Putin’s government is diving fully into trying to solve the country’s budgetary problems, but it doesn’t help much. The corporate profit tax was raised from 20% to 25% on January 1, 2025, and now, a VAT increase from 20% to 22% is planned to take effect on January 1, 2026. But it all won’t help much. The additional corporate profit tax collection due to the tax rate increase in 2025 is supposed to generate an additional RUR 1.7 trillion ($21 billion) of revenue for the budget, which is just a fraction of the 2025 deficit planned so far — RUR 5.7 billion ($71 billion).

It’s the same story with the VAT increase in 2026: it is also supposed to generate an additional RUR 1.7 trillion of revenue, which will not solve even half of the 2026 budget deficit problem (budget deficit for 2026 is expected to be RUR 3.8 trillion even after the VAT increase).

Tax hikes don’t help to raise revenue sufficient to solve the deficit problem — but they definitely contribute to the economic slowdown. This was admitted even by pro‑government economists like the Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short‑Term Forecasting founded by current Minister of Defense Andrey Belousov and chaired today by his brother Dmitry — which suggested last year that the profit tax hike from 2025 will have negative contribution to fixed investment dynamics of 0.4%. Now, officials admit that the VAT increase in January 2026 will contribute to higher inflation, and through that, will negatively impact interest rates and growth.

Against the background of near‑full depletion of the state’s financial reserves, expensive borrowing, lack of access to international financial markets, and the potential for tax hikes nearly exhausting, the only option left for the government is effectively resorting to the Central Bank’s credit to the government — e.g. monetary emission used to close the budgetary deficit. This measure was widely used in Russia in the 1990s, causing hyperinflation.

Putin’s government has already used de‑facto Central Bank credit to the government to finance the budget deficit in 2022 and 2024. The scheme works as follows:

Against the background of near‑full depletion of the state’s financial reserves, expensive borrowing, lack of access to international financial markets, and the potential for tax hikes nearly exhausting, the only option left for the government is effectively resorting to the Central Bank’s credit to the government — e.g. monetary emission used to close the budgetary deficit. This measure was widely used in Russia in the 1990s, causing hyperinflation.

Putin’s government has already used de‑facto Central Bank credit to the government to finance the budget deficit in 2022 and 2024. The scheme works as follows:

Here’s how this scheme was used in December 2024: The Russian Ministry of Finance announced additional auctions to raise around RUR 2 trillion through OFZ bonds, while the Central Bank simultaneously made the monthly repo auctions available for banks participating in the OFZ purchase. Previously, similar scheme with pre‑arranged buy‑off of OFZ worth around RUR 3 trillion was also used in December 2022.

Through this scheme, Minfin was able to fulfill its borrowing plan for 2024 (however, to little positive fiscal effect, as debt raised was expensive — but still, the expenditure bills were paid).

The Central Bank initially promised that monthly repo auctions will be «strictly temporary and non‑inflationary,“ and that the banks will simply repay the repo loans in due time. However, as of October 2025, the Central Bank has not kept its promise to halt monthly repo auctions, and keeps rolling the banks' debt over, having switched from monthly to weekly repo auctions in April 2025. If this scheme will be extended in time, this will be no different from direct lending to the Government by the Central Bank.

Here’s how this scheme was used in December 2024: The Russian Ministry of Finance announced additional auctions to raise around RUR 2 trillion through OFZ bonds, while the Central Bank simultaneously made the monthly repo auctions available for banks participating in the OFZ purchase. Previously, similar scheme with pre‑arranged buy‑off of OFZ worth around RUR 3 trillion was also used in December 2022.

Through this scheme, Minfin was able to fulfill its borrowing plan for 2024 (however, to little positive fiscal effect, as debt raised was expensive — but still, the expenditure bills were paid).

The Central Bank initially promised that monthly repo auctions will be «strictly temporary and non‑inflationary,” and that the banks will simply repay the repo loans in due time. However, as of October 2025, the Central Bank has not kept its promise to halt monthly repo auctions, and keeps rolling the banks' debt over, having switched from monthly to weekly repo auctions in April 2025. If this scheme will be extended in time, this will be no different from direct lending to the Government by the Central Bank.

In the absence of other ways to fill the budget spending gap, it is most certain that Russia will resort more and more to monetary emission as a major tool of managing the budget deficit. In September 2025, the Russian Ministry of Finance announced an increase in 2025 federal government borrowing plans by RUR 2.2 trillion — while it is unlikely that additional demand for OFZ state bonds will be found at the market, this most certainly reflects the intent to repeat the “repo to OFZ” scheme with involvement of state banks in December 2025. (Borrowing from state banks through the “repo to OFZ” scheme is also not cheap, but its nonetheless manageable by the state, and, under this scheme, demand for OFZ will be guaranteed.)

Naturally, all of this will have a further negative effect on inflation. The war against Ukraine already sparked an enormous growth of money supply. From 2022–2025, monetary supply in Russia doubled: the M2 aggregate has increased from RUR 62 trillion in December 2021 to RUR 120 trillion in August 2025, increasing from 46% to 56% of GDP. As admitted by Andrey Gangan, the Russian Central Bank’s Director of Monetary Policy:

In the absence of other ways to fill the budget spending gap, it is most certain that Russia will resort more and more to monetary emission as a major tool of managing the budget deficit. In September 2025, the Russian Ministry of Finance announced an increase in 2025 federal government borrowing plans by RUR 2.2 trillion — while it is unlikely that additional demand for OFZ state bonds will be found at the market, this most certainly reflects the intent to repeat the “repo to OFZ” scheme with involvement of state banks in December 2025. (Borrowing from state banks through the “repo to OFZ” scheme is also not cheap, but its nonetheless manageable by the state, and, under this scheme, demand for OFZ will be guaranteed.)

Naturally, all of this will have a further negative effect on inflation. The war against Ukraine already sparked an enormous growth of money supply. From 2022–2025, monetary supply in Russia doubled: the M2 aggregate has increased from RUR 62 trillion in December 2021 to RUR 120 trillion in August 2025, increasing from 46% to 56% of GDP. As admitted by Andrey Gangan, the Russian Central Bank’s Director of Monetary Policy:

“In the last 25 years, there hasn’t been a single episode of such a sharp increase in the money supply over such a short period”.

“In the last 25 years, there hasn’t been a single episode of such a sharp increase in the money supply over such a short period”.

Very much as was predicted by many, Russia ran into major difficulties with continuing its war against Ukraine in 2025, not the least due to budget constraints. Here are the most important ways the budget crisis impacts the financing of the war:

Very much as was predicted by many, Russia ran into major difficulties with continuing its war against Ukraine in 2025, not the least due to budget constraints. Here are the most important ways the budget crisis impacts the financing of the war:

The latter factor isn’t directly related to the federal fiscal situation — regional payments for signing military contracts are made from regional budgets. However, it is important to note that Russia’s budget crisis also greatly reduces the ability of the federal center to provide financial assistance to the Russian regions. It is expected that, in 2025, total federal financial aid to regions will be cut for the third consecutive year (in 2026, they are expected to be increased only by 7.6%, still not reaching the pre‑2025 numbers). At the same time, most regions face sharply increasing budget deficits due to economic contraction, lack of investment and pressure on expenditures. In the third quarter of 2025, over three quarters of Russian regions (67) faced budget deficits, and the situation is likely to deteriorate further. This will cap the regions' ability to contribute to the general war budget, including through paying generous sign‑up bonuses for signing a military contract, which have recently been sharply reduced.

The latter factor isn’t directly related to the federal fiscal situation — regional payments for signing military contracts are made from regional budgets. However, it is important to note that Russia’s budget crisis also greatly reduces the ability of the federal center to provide financial assistance to the Russian regions. It is expected that, in 2025, total federal financial aid to regions will be cut for the third consecutive year (in 2026, they are expected to be increased only by 7.6%, still not reaching the pre‑2025 numbers). At the same time, most regions face sharply increasing budget deficits due to economic contraction, lack of investment and pressure on expenditures. In the third quarter of 2025, over three quarters of Russian regions (67) faced budget deficits, and the situation is likely to deteriorate further. This will cap the regions' ability to contribute to the general war budget, including through paying generous sign‑up bonuses for signing a military contract, which have recently been sharply reduced.

As can be seen from the limited scope of operations and limited achievements of Russia’s much‑advertised “Summer offensive” of 2025 on the battlefield in Ukraine, financial constraints have already put the brakes on Russia’s ability to conduct large‑scale offensive operations across the frontline. This situation will exacerbate further. However, this is not to say that Russia won’t be able to launch massive missile and drone attacks against Ukraine, or limited offensive operations across several points along the frontline — for such limited scale operations, financial resources will still be available. But large‑scale offensives of the magnitude of 2022 are not possible anymore given the current constraints.

As can be seen from the limited scope of operations and limited achievements of Russia’s much‑advertised “Summer offensive” of 2025 on the battlefield in Ukraine, financial constraints have already put the brakes on Russia’s ability to conduct large‑scale offensive operations across the frontline. This situation will exacerbate further. However, this is not to say that Russia won’t be able to launch massive missile and drone attacks against Ukraine, or limited offensive operations across several points along the frontline — for such limited scale operations, financial resources will still be available. But large‑scale offensives of the magnitude of 2022 are not possible anymore given the current constraints.

While a budget deficit of around 2% of GDP may not seem too much of a problem for an outside observer under normal circumstances, the current Russian situation is anything but “normal.”

Russia finds itself in a protracted budget crisis, facing 7 consecutive years of budget deficits around 2% of GDP or more. While the depth of budget problems is not as serious as in the early 1990s, in a certain sense, the situation is much worse. In the 1990s, Russia opened up internationally, reconciled with the West, and pursued major economic reforms, which resulted in remarkable economic growth and improvement of the situation into the late 1990s.

Currently, the situation is moving in the opposite direction, and there seems no end in sight to the Russian economy’s problems — and the recently unveiled federal budget for 2026–2028 confirms just that, and endless budget deficit on the background of sluggish growth. Russia is not able to borrow money internationally due to sanctions, even China is not ready to provide access for Russia to its domestic financial market — the opportunity to issue yuan‑denominated bonds by the Russian government has been closed. Domestic borrowing is too expensive under current inflation and interest rates and doesn’t make much difference in terms of reducing the deficit — because the cost of servicing debt is too high. The government’s financial reserves are nearly fully depleted. Taxes have been raised extensively in the past years, and there’s limited space to continue doing it.

The only remaining option — which the government seems to be resorting to — is effectively the Central Bank’s credit to government masked under a “repo to OFZ” scheme, with involvement of large banks as intermediaries. As a result, money supply is skyrocketing, negatively impacting inflation and hampering the Central Bank’s efforts to bring prices under control.

At the meeting of its board on key interest rate on October 24, 2025, the Russian Central Bank has publicly admitted an array of these problems — the pro‑inflationary nature of budget deficits, the negative impact of raising VAT on prices and the economy — and revised the forecast for key interest rate trajectory to 13–15% for 2026 (previously forecast at 12–13%). At the same time, Sberbank’s CEO German Gref suggested earlier at the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok that revival of investment activity will not be possible until the Central Bank lowers the key interest rate at least below 12%.

Russia’s economic and budget crisis deepens, which is the direct result of the impact of Western sanctions. It already greatly impacts Russia’s ability to wage war against Ukraine — the Russian military industry is slowing down and faces multiple economic problems, the government’s ability to provide military servicemen with adequate pay is shrinking. While Russia can still continue to wage the war, financial difficulties have greatly limited its ability to conduct large‑scale offensive operations. The current crisis will have major impact on the war in Ukraine and Russia’s international posturing in the near and medium‑term future. We will continue to monitor these developments in our regular reports.

While a budget deficit of around 2% of GDP may not seem too much of a problem for an outside observer under normal circumstances, the current Russian situation is anything but “normal.”

Russia finds itself in a protracted budget crisis, facing 7 consecutive years of budget deficits around 2% of GDP or more. While the depth of budget problems is not as serious as in the early 1990s, in a certain sense, the situation is much worse. In the 1990s, Russia opened up internationally, reconciled with the West, and pursued major economic reforms, which resulted in remarkable economic growth and improvement of the situation into the late 1990s.

Currently, the situation is moving in the opposite direction, and there seems no end in sight to the Russian economy’s problems — and the recently unveiled federal budget for 2026–2028 confirms just that, and endless budget deficit on the background of sluggish growth. Russia is not able to borrow money internationally due to sanctions, even China is not ready to provide access for Russia to its domestic financial market — the opportunity to issue yuan‑denominated bonds by the Russian government has been closed. Domestic borrowing is too expensive under current inflation and interest rates and doesn’t make much difference in terms of reducing the deficit — because the cost of servicing debt is too high. The government’s financial reserves are nearly fully depleted. Taxes have been raised extensively in the past years, and there’s limited space to continue doing it.

The only remaining option — which the government seems to be resorting to — is effectively the Central Bank’s credit to government masked under a “repo to OFZ” scheme, with involvement of large banks as intermediaries. As a result, money supply is skyrocketing, negatively impacting inflation and hampering the Central Bank’s efforts to bring prices under control.

At the meeting of its board on key interest rate on October 24, 2025, the Russian Central Bank has publicly admitted an array of these problems — the pro‑inflationary nature of budget deficits, the negative impact of raising VAT on prices and the economy — and revised the forecast for key interest rate trajectory to 13–15% for 2026 (previously forecast at 12–13%). At the same time, Sberbank’s CEO German Gref suggested earlier at the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok that revival of investment activity will not be possible until the Central Bank lowers the key interest rate at least below 12%.

Russia’s economic and budget crisis deepens, which is the direct result of the impact of Western sanctions. It already greatly impacts Russia’s ability to wage war against Ukraine — the Russian military industry is slowing down and faces multiple economic problems, the government’s ability to provide military servicemen with adequate pay is shrinking. While Russia can still continue to wage the war, financial difficulties have greatly limited its ability to conduct large‑scale offensive operations. The current crisis will have major impact on the war in Ukraine and Russia’s international posturing in the near and medium‑term future. We will continue to monitor these developments in our regular reports.

By Vladimir Milov

September 24, 2025

Article

Article When the rhetoric of an “unlimited alliance” faces economic reality

By Vladimir Milov

October 15, 2025

Report

Report Structure, composition and ways to improve effectiveness

By Vladimir Milov

August 23, 2025

By Vladimir Milov

September 24, 2025

Article

Article When the rhetoric of an “unlimited alliance” faces economic reality

By Vladimir Milov

October 15, 2025

Report

Report Structure, composition and ways to improve effectiveness

By Vladimir Milov

August 23, 2025