The Transition Project: Establishing the Rule of Law

By Ekaterina Mishina May 29, 2024

By Ekaterina Mishina May 29, 2024

There is no universally accepted definition of the Rule of Law. Tens of thousands of books and scholarly articles discuss this concept in different ways without offering a generally accepted definition. The International Bar Association Council in its “Rule of Law” Resolution1 of September 2005 describes the essential characteristics of the Rule of Law, which, as noted by Francis Neate, president of the IBA in 2005–2006, essentially rest upon two pillars: Submission of all to the Law and The Separation of Powers2. The 2005 “Rule of Law” IBA Resolution declares that “the International Bar Association (IBA), the global voice of the legal profession, deplores the increasing erosion around the world of the Rule of Law. The IBA welcomes recent decisions of courts in some countries that reiterate the principles underlying the Rule of Law.

These decisions reflect the fundamental role of an independent judiciary and legal profession in upholding these principles. The IBA also welcomes and supports the efforts of its member Bar Associations to draw attention and seek adherence to these principles. An independent, impartial judiciary; the presumption of innocence; the right to a fair and public trial without undue delay; a rational and proportionate approach to punishment, a strong and independent legal profession; strict protection of confidential communications between lawyer and client; equality of all before the law; these are all fundamental principles of the Rule of Law.”

The 2005 “Rule of Law” ABA Resolution describes the phenomena that are totally incompatible with the Rule of Law: arbitrary arrests; secret trials; indefinite detention without trial; cruel or degrading treatment or punishment; intimidation

or corruption in the electoral process. Regrettably, all these phenomena are found in today’s Russia.

The working definition of the Rule of Law suggested by the World Justice Project includes four universal principles: accountability (the government as well as private actors are accountable under the law), just law (the law is clear, publicized, and stable and is applied evenly. It ensures human rights as well as property, contract, and procedural rights), open government (the processes by which the law is adopted, administered, adjudicated, and enforced are accessible, fair, and efficient), accessible and impartial justice (Justice is delivered in a timely manner by competent, ethical, and independent representatives and neutrals who are accessible, have adequate resources, and reflect the makeup of the communities they serve)3.

The Venice Commission addressed the issue of the Rule of Law in its 2011 report4, in which it stated that “The concept of the “Rule of Law”, along with democracy and human rights, makes up the three pillars of the Council of Europe and is endorsed in the Preamble to the European Convention on Human Rights”5. After examining the historical origins of the concepts of Rule of Law, Rechtsstaat and Etat de droit, the report looked at these concepts in positive law. The term Rechtsstaat is found in a number of provisions of the Fundamental Law of Germany6. The notion of the rule of law (or of Rechtsstaat/Etat de droit) appears as a main feature of the state in a number of constitutions of former socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe (Albania, Armenia, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Moldova, Montenegro, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, “the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia”, Ukraine). It is more rare in old democracies (Andorra, Finland, Germany, Malta, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey). It can be mostly found in preambles or other general provisions7.

Importantly, the Venice Commission pointed out that the notion of the Rule of Law is often difficult to apprehend in former socialist countries, which were influenced by the notion of socialist legality8. Under socialism, Marxist‑Leninist ideology was the pillar of the new system of law; it penetrated into all areas of

law, superseding them with a class approach. Marxism/Leninism viewed law as a tool intended to maintain the dominance of the working class over non- proletarians. Law was needed as a necessary, but temporary instrument used in the best interests of the working people, which would not be needed after creation of a classless society and would inevitably disappear9. This was a poor basis for establishing the Rule of Law.

While drafting the report, the Venice Commission reflected on the definition of the Rule of Law and concluded that the Rule of Law was indefinable. However, even in the absence of such definition and despite considerable diversity of opinion as to the meaning of the Rule of Law, the Rule of Law is an existing constitutional principle both in civil law and common law systems10. As suggested by the Venice Commission, the following definition by Tom Bingham, Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, probably covers most appropriately the essential elements of the rule of law: “all persons and authorities within the state, whether public or private, should be bound by and entitled to the benefit of laws publicly made, taking effect (generally) in the future and publicly administered in the courts”11. This short definition, which applies to both public and private bodies, is expanded by 8 “ingredients” of the rule of law. These include: (1) Accessibility of the law (that it be intelligible, clear and predictable); (2) Questions of legal right should be normally decided by law and not discretion; (3) Equality before the law; (4) Power must be exercised lawfully, fairly and reasonably; (5) Human rights must be protected; (6) Means must be provided to resolve disputes without undue cost or delay; (7) Trials must be fair, and (8) Compliance by the state with its obligations in international law as well as in national law12.

The Venice Commission took an operational approach and concentrated on identifying the core elements of the Rule of Law. The Commission then decided to draft an operational tool for assessing the level of Rule of Law compliance in any given state, and this led to the elaboration in 2016 of the Rule of Law Checklist13, based on the five core elements of the Rule of Law, sub‑itemized into detailed questions. These core elements are:

functional democracy. It includes supremacy of the law: State action must be in accordance and authorized by the law. The law must define the relationship between international law and national law and provide for the cases in which exceptional measures may be adopted in derogation of the normal regime of human rights protection.

I will begin the analysis of the current state of affairs in Russia by discussing the issue of prevention of abuse/misuse of power in Russia with the focus on the principle of separation of powers as a fundamental constitutional principle and a pillar of the Rule of Law. Then I will describe how other core elements of the Rule of Law formulated by the Venice Commission look in today’s Russia and what needs to be done in this realm. Challenges of creating an independent and impartial judiciary as a key problem for Russia’s transition will be discussed separately.

As proclaimed in the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, any society in which no provision is made for guaranteeing rights or for the separation of powers has no Constitution15. Sadly, Russia is getting closer to being such a society: constitutional guarantees of rights and freedoms have stopped working, the fundamental rights and freedoms are being violated by the Russian public authorities and law enforcement officers. Constitutional provisions on the separation of powers seemingly remain intact, but in today’s Russia the system of separation of powers is in danger, and the system of checks and balances is non‑existent.

For the first time in the history of the USSR and Russia, separation of powers was proclaimed in the Declaration on the State Sovereignty of the RSFSR on June 12, 1990, but was envisaged on the constitutional level only in April of 199216. This new constitutional provision was in sharp contrast with Art. 104 of the RSFSR Constitution of 197817, which established that the Congress of People’s Deputies was the supreme body of power of the Russian Federation and could handle any issue related to the competence of the RF.

The Russian version of the principle of separation of powers embodied in the Constitution of 1993 was flawed from the very beginning. Art. 10 of the Russian Constitution provides that “State power in the Russian Federation shall be exercised on the basis of its division into legislative, executive and judicial authority. Bodies of legislative, executive, and judicial authority shall be independent”. At first sight, and read in isolation, this provision might be taken to suggest that the constitutional system of the Russian Federation is characterized by a classic trias politica division of power. However, the principle enshrined in Art. 10 of the Constitution cannot be interpreted in isolation from the provisions contained in the subsequent chapters and Articles of the Constitution18. While taken together, these constitutional provisions clearly show that the attribution

of powers in the 1993 Constitution is far from a strict trias politica division of power. Rather, the Constitution grants considerable powers to the President, who is not a part of the system of separated powers. Professor M. Krasnov and Professor I. Shablinsky point out that “having excluded the Russian President from the triad of branches of power, the Constitution places hum above these branches”19.

Many prominent Russian legal scholars have noted that Russian constitutional entrenchment of separation of powers is obviously unbalanced, as the president is the strongest and the most powerful actor. Professor V.S. Nersesyanz explains that there is a “clear overbalance of the Presidential powers and his prevailing role in handling public affairs and the obvious weakness of other branches of power compared to the Presidential power”20. Moreover, the President is present in all branches of power: Professor V. Zorkin and Dr. L. Lazarev emphasize that though the Russian President remains outside the traditional triad of branches of power, he “integrates Russian statehood […] and is “present” in all branches of power both de jure and de facto”21. Professor Y. Dmitriyev agrees by stating that “Furthermore, the required system of ‘checks and balances’ of the joint activities of the Federal Assembly, the President of the RF and the RF Government is not defined. A significant imbalance in favour of the executive power exists in Russia, which, through the RF President, who is its de facto head, dominates the other branches”22. According to Nersesyanz, “the meaning of a number of other articles [of the Constitution] indicates that presidential power seems to be placed out of the bounds of the classic triad and to be constructed as a separate (initial, basic) power that sits above this standard triad”23.

This unique position of the Russian President was strengthened by the constitutional provision establishing that the President of the RF determines the guidelines of the state’s domestic and foreign policies (Art. 80 p. 3). This very odd norm, which migrated from the Soviet constitutions into the post- Soviet one, apparently disagrees with the principle of separation of powers. The mandatory nature of these guidelines of the state’s domestic and foreign policies, which was confirmed by the Russian Constitutional Court24, allows the

Russian President to dictate his orders to other branches of power and makes the entire constitutional system even more unbalanced.

Numerous alterations of the Russian Constitution did not improve this imbalance, and the crucial point was reached in 2020. The 2020 constitutional amendments did not just “zero out” Vladimir Putin’s presidential terms (as well as Dmitriy Medvedev’s, although that is rarely mentioned), thereby essentially allowing him to stay in office indefinitely, but also extended his powers. Now the president can do the following:

In his famous book “The Imperial Presidency”27 Arthur Schlesinger addresses several characteristics of an Imperial Presidency, inter alia, the diminished

influence of the Cabinet and the rise of a Presidential court, whereby the President is increasingly reliant on personal advisors in areas where he has Cabinet Departments. In my view, this wording is applicable to Putin’s Russia, where members of the Government oftentimes play a less important role compared to the members of the Presidential court, which is usually called the President’s inner circle. This inner circle started to form shortly after Putin’s rise to power. Remarkably, in early 2000, Putin declared the principle of “equidistance of oligarchs”: “No clan, no oligarch should be close to regional and federal authorities, they must be equidistant from power”28. In so doing, the president sent an unequivocal message that he was changing the rules: wealthy people from the 1990s era should not get involved in politics, and they’d better keep a low profile. Simultaneously, Putin launched the “second wave of oligarchs,” replacing the oligarchs of the 1990s with his own old friends. The Forbes list includes several Russian businessmen known as “Putin’s friends”, who became ultra‑rich mostly with the help of governmental contracts. However, the mere fact of being ultra‑rich is not sufficient to be an oligarch in Russia. Russian economists Sergey Guriev and Andrey Rachinsky point out that under Putin’s rule a Russian oligarch is a businessman who possesses sufficient resources to affect national policy29.

Putin’s “inner circle” includes people, who were close to him before his political career on the federal level took off. These are people who know Putin from his time in Saint Petersburg or are his longtime St. Peterburg friends (Yuri Kovalchuk, Gennady Timchenko, Arkady and Boris Rotenberg) or colleagues from his days in the St. Petersburg Mayor’s Office or the Dresden KGB rezidentura (station): (Alexey Miller, Sergey Chemezov, etc.). Putin’s new elite also includes people from the KGB, who underwent professional training together with him in the 1980s. These people constitute another type of Putin’s oligarchs — leaders of Russia’s security services, the police, and the military, known as the “siloviki”,30 who have also leveraged their networks to amass extreme personal wealth. In most cases, “siloviki” are presidential appointees, who are assigned to these top governmental positions at the President’s sole discretion. Under the 1997 Federal Constitutional Law “On the Government of the RF”, the President “directs

activities of the federal organs of executive power in charge of defense, internal security affairs, justice, foreign affairs, prevention of emergency situations and liquidation of consequences of calamities […] and appoints heads and deputy heads of these organs upon the recommendation of the Chairman of the RF Government”31. This presidential power existed from the late 1990s and in 2020 was elevated on the constitutional level in a slightly modified version32. Now the aforementioned heads of federal organs of executive power (plus the one in charge of “public safety”) are appointed by the President after consultations with the upper house of the federal parliament; recommendation of the Chairman of the Government is not even mentioned. Similar provision can be found in the new FCL “On the Government of the RF”33.

Elimination of the presidential power to make appointments to top governmental positions “after consultations with the Federation Council” is one of the most important conditions for establishing the Rule of Law in Russia. Such consultations are purely symbolic: they were supposed to create an impression of the active role of the Federation Council in the procedure of governmental appointments (with little success). These consultations do not address legal consequences and they have zero impact on the presidential decision‑making process. The upper house of the Russian federal legislature must be more actively involved in the procedure of appointments to public positions. The President shall seek advice and obtain the consent of the Federation Council before making nominations to public positions (including judicial appointments, in most of which the President currently has a final say34). The RF Law “On the Status of Judges” of 1992 shall be amended accordingly.

The biggest challenge to the initiation of the process of constitutional changes will be selection of the constitutional system for a new democratic Russia. Another big question relates to the destiny of the 1993 Russian Constitution. The idea to repeal the existing Constitution and to start from scratch looks unrealistic. At least for some time Russia must live with the properly amended 1993 Constitution. Correction of the defects of the 1993 Constitution (both

initial and those that came in a form of constitutional amendments) shall be one of the pillars of this stage of the constitution‑making process. Repeal of Putin’s constitutional amendments‑2020 and some previous amendments (with the amendment envisaging elimination of the Higher Arbitrage Court of the RF in the first instance) will be a conditio sine qua non.

In the longer term, Russia must base its constitution‑making process on the lessons learned from its past, and here the post‑World War II experience of West Germany would be one of the best foreign models to use. However, irrespective of what the final choice might be, it would be feasible to follow the pattern of post‑WWII Germany, which did its best to learn the lessons of the Nazi regime. Design of the 1949 Basic Law of Germany demonstrates that its drafters avoided the flaws of the 1919 Weimar Constitution. The 1949 Basic Law strengthened the status and powers of the Parliament and the Federal Government in order to ensure proper functioning of the parliamentary system. The powers of the federal president were accordingly narrowed. It was also decided to eliminate all elements of direct democracy, which in the light of the Weimar Republic’s experience were perceived to be a potential or direct threat to the normal operation of the parliamentary constitutional system35. The direct response to Putin’s undemocratic regime must come, inter alia, in a form of constitutional provisions guaranteeing protection to human rights and human dignity and making these fundamental rights binding for all organs of the state as directly applicable law (exactly as it was done in the German Basic Law of 1949)36.

A well‑balanced system of separated powers with downsized presidential powers from the outset will be another essential part of establishing the Rule of Law. Certain constitutional provisions that infringe upon the principle of separation of powers (such as Art. 80 p. 3 discussed above) or the provision empowering the President to appoint up to 30 “senators”37 to the upper house of the federal legislature38) shall be repealed. Constitutional provisions envisaging the powers and competence of branches of power shall include a more clearly established system of checks and balances. It would be incorrect to state that

Russian constitutional design initially had no place for checks and balances. Ilya Shablinsky notes that checks and balances were activated many times. He points out that norms aimed at restraining the presidential powers in relations with both houses of the federal parliament were actively applied in 1994–1999 and were never in use after 200039.

The 2020 amendments further deepened this imbalance of power and strengthened the role of the President, while the other branches of government were virtually deprived of the opportunity to influence him. The State Duma may charge the president with high treason or another serious crime, but the offense must be confirmed by: (1) the conclusion of the Supreme Court on the presence of all criminal elements in the President’s activities; (2) the conclusion of the Constitutional Court40 on the compliance with the established procedure for the pressing of charges. The chances of the charge making it through such a complicated procedure are almost next to zero. First, the decision of the Duma to press charges should be upheld by two‑thirds of the votes of the total number of deputies in the Duma. In the history of Russia there have been three attempts of impeachment (two in 1993 under the 1978 Constitution of the RSFSR and one in 1999), and the required number of votes has never been collected. Secondly, if one is to take into account the President’s new authority to initiate the termination of the powers of Supreme and Constitutional Court judges, as well as of chairpersons and their deputies, the judges of the Russian Federation’s high courts will think ten times before giving unfavorable conclusions – for they can pay for this with their posts41. Grounds for impeachment as established in the Russian Constitution must be essentially re‑worked and more focused on the President’s incompatibility with his high office. The following wording can be used as a possible model : “The President of the Republic shall not be removed from office during the term thereof on any grounds other than a breach of his duties patently incompatible with his continuing in office”42 or “the President can be removed from office on the following grounds: (1) for violation of the Constitution and laws, (2) for illegal interference into powers of Zhogorku

Kenesh43, activities of the organs of judicial power”44.

With a functioning (as opposed to fictional) system of separated powers in place, other issues and problems related to establishing the Rule of Law in Russia would be addressed with greater success.

The principle of legality sounds somewhat questionable in Putin’s Russia due to the increasing number of unlawful laws adopted by the Russian Parliament (the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation) under Putin’s rule. Nevertheless, from his first days in office, Putin has usually been referred to as a “legalist” : “Putin is a legalist, i.e. a public official, who reaches his goals by legal means within the framework of the existing legal order”45. On January 31, 2000, one month exactly after becoming acting President of the Russian Federation, while speaking at a meeting in the Russian Ministry of Justice, he offered language, which immediately turned into a mantra: “Whatever we are up to today […], we must remember about the long‑standing Russian traditions of fairness and legitimacy, remember that the dictatorship of laws is the only type of dictatorship we must succumb to”. The dogma “dictatorship of laws” became one of the keynote ideas of the first two presidential terms of Vladimir Putin46.

Putin’s love for laws drafted in accordance with his preferences should not be mistaken for a love for the Law. Putin and his obedient law‑makers repeatedly ignore and violate fundamental legal principles. Numerous unlawful laws adopted under Putin’s rule leave no doubt that in contemporary Russia the word “legalist” has assumed a different meaning: love for Putin’s laws, some of which not only disagree with fundamental legal principles — they are totally unlawful. If a country adopts illegitimate laws that violate generally accepted legal principles and legitimize arbitrariness at the legislative level, the

consequences may be terrifying: it is well‑known that the law can be used in order to legitimize the worst lawlessness. The most glaring example of such a misuse is the infamous Nuremberg Laws, including the “Reich Citizenship Law” and the “Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor”, which deprived Jews of German citizenship, dictated that they wear clothes in “Jewish” colors, and forbade marriage and sexual relations between Jews and members of the “Aryan” race. As noted by Dr. Rainer Grote, “the experience of the National Socialist regime, which used the legislative and administrative bodies at its sole discretion to cloak even the most outrageous and egregious policies in the garb of formal legality, dealt a fatal blow to the positivist concept of Rechtsstaat”47.

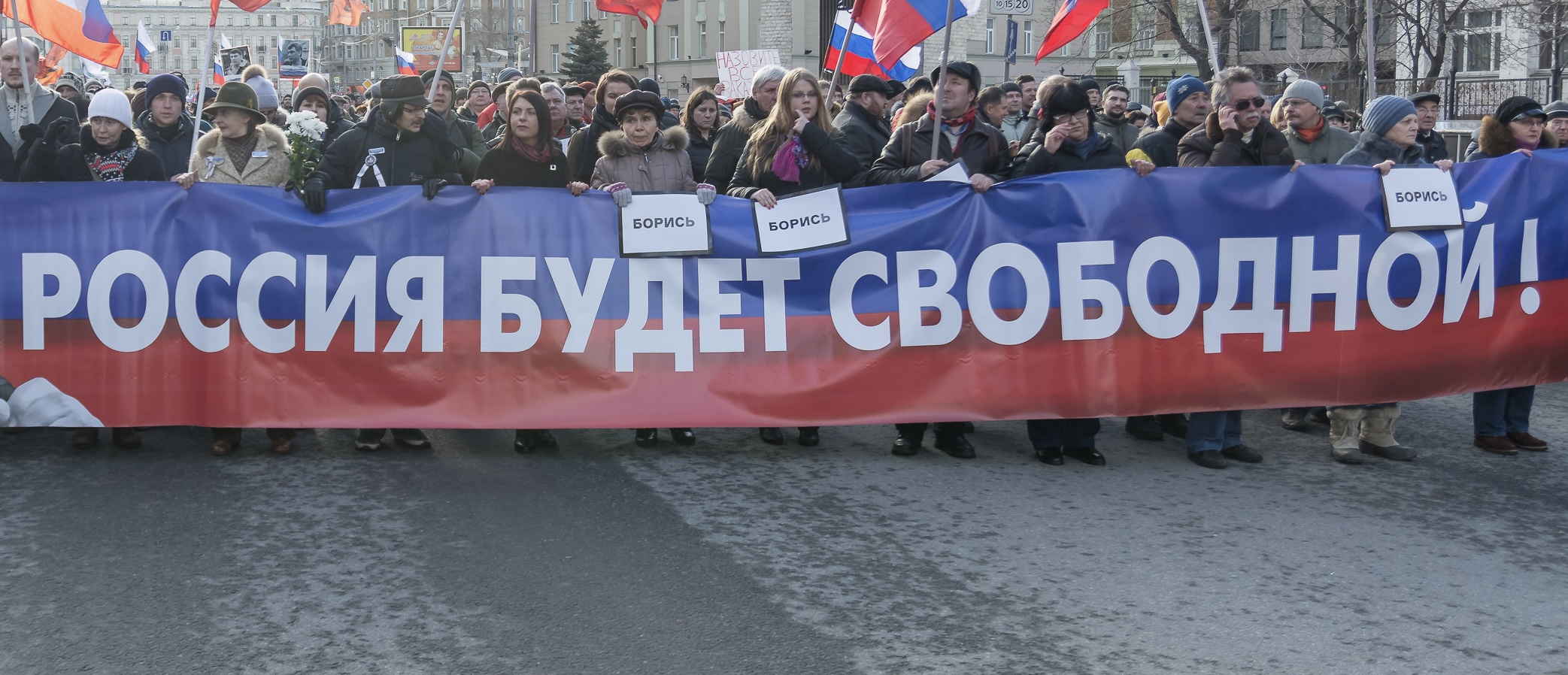

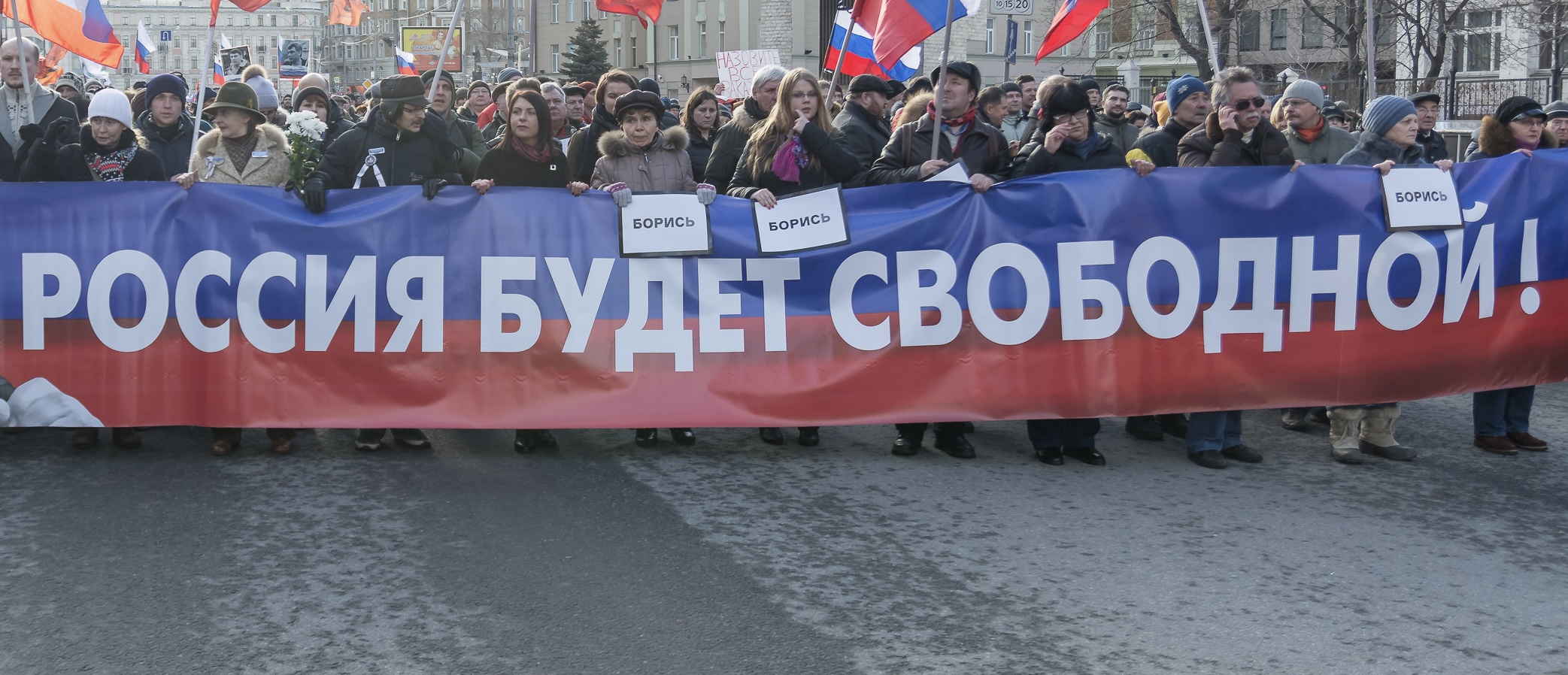

The most telling examples of Russian unlawful laws are the infamous “Dadin’s48 Article” of the Russian Criminal Code and the legislation on “undesirable organizations”. In 2014, Article 212.1 of the Criminal Codecriminalized “repeated violations of the established rules of organizing or holding public gatherings, meetings, rallies, marches, and pickets”49. Many prominent Russian lawyers including famous defense attorney Henri Reznik pointed out the anti- constitutional nature of this article and emphasized that multiple and repetitive administrative offenses do not constitute a crime, as criminal acts are associated with a higher level of danger to the public.50 The introduction of this article to the Russian Criminal Code was motivated solely by political expediency and the urge to fight the opponents of the regime. As for punishment, just like in feudal times, it serves as intimidation to teach others not to dissent51: Article

212.1 stipulates a maximum penalty of five years, which qualifies such offenses as medium‑gravity crimes.

The notion of an “undesirable organization” was specifically designed for labeling and blocking activities of foreign and international NGOs which the Russian government doesn’t like for various reasons. Legislation on “undesirable organizations” was adopted in 2015, when the Federal Law “On Enforcement

Actions for Individuals Involved in Violation of Fundamental Human and Civil Rights and Freedoms” of 2012 was amended. New Art 3.1. envisaged that “Activities of a foreign or international NGO endangering fundamentals of the constitutional system of the Russian Federation, defensive capacity or safety of the state, which, inter alia, help or interfere with nomination of candidates, election of registered candidates, proposing and conducting of referenda, securing of certain results on elections or referenda… can be designated as undesirable on the territory of the Russian Federation”52. Decisions on “undesirability” of a foreign or international NGO are made by the General Prosecutor of the RF or her deputies upon coordination with the RF Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Notably, Russian legislation lacks precise criteria for identifying “undesirability” of operations of a foreign or international NGO in the territory of Russia, so the decisions are made at the sole discretion of the Russian authorities. Labeling of such NGOs as “undesirable organizations” is politically motivated, so discussing the issue of the danger or threat posed by undesirable organizations”, which is kept by the Russian Ministry of Justice, confirms that declaring a foreign\international NGO an “undesirable organization” is always politically motivated. The list starts from The National Endowment for Democracy; Open Society Foundation, Atlantic Council, Oxford Russia Fund, Bard College, Journalism Development Network INC, Chatham House and other reputable NGOs designated shortly thereafter. The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars was put on the list in November 2022. The Andrei Sakharov Foundation was declared an “undesirable organization”53 on January 23, 2023. Declaring Transparency International an “undesirable organization” on March 6, 2023, confirmed that an old joke “Anti‑corruption efforts must be criminalized because they undermine the fundamentals of Russian statehood” was not a joke.

The designated status of “undesirable organization” entails a number of consequences including a ban on opening new subdivisions and closing of already existing ones, a ban on disseminating information materials (including via media and Internet), a ban on carrying out programs and projects on the territory of Russia. Legislative provisions on “undesirable organizations” prohibit Russian citizens, stateless persons permanently residing in Russia and Russian

legal entities from taking part in the activities of an “undesirable organization” outside Russia54. Participation in activities of an “undesirable organization” constitutes an administrative offence55. Art. 284.1 “Carrying out activities of an “undesirable organization”56 established criminal liability for (1) participation in activities of an “undesirable organization” committed by an individual already held liable for a similar offence or convicted under this Article, (2) providing or collecting money or rendering financial services intended for maintenance of activities of an “undesirable organization”, (3) management of operations of an “undesirable organization”. With the maximum punishment specified as deprivation of freedom for up to 6 years, this crime constitutes a felony under Russian law57.

Another example of Putin’s unlawful legislation is the “falsification of history” provision. In May 2014, a new Article 354.1 “Rehabilitation of Nazism» was added to the Russian Criminal Code. The new article criminalized “Denial of facts established by the verdict of the International Military Tribunal in order to bring to justice and punish key military criminals of the European Axis powers, approving of crimes established by this verdict as well as public dissemination of knowingly false information regarding activity of the USSR during World War II”58. Russian case law proves that the provision on “public dissemination of knowingly false information regarding activity of the USSR during World War II” is the most important and the most utilized provision of this article. In most criminal proceedings instituted under Article 354.1, suspects faced charges of dissemination of such information. Such cases are usually referred to as cases of “falsification of history”, and the number of cases is on the rise59. 2020 brought additional risks for those who were brave enough to criticize certain events from Russia’s history: protection of “historical truth” was elevated to the constitutional level. One of the amendments to the Russian Constitution established that “The Russian Federation venerates the memory of the

defenders of the Motherland and ensures protection of historical truth”60. Shortly after the constitutional amendments came into effect on July 04, 2020, the RF Investigatory Committee created a new subdivision in charge of investigating crimes connected with “falsification of history”. In April of 2021, the definition of “Rehabilitation of Nazism” was expanded61 and now includes (a) committing a crime by a group of persons, by the group of persons with a prior record of conspiracy or by an organized group, (b) with the use of the Internet or other information/communication networks, © public humiliation of the honor and dignity of a veteran of the Great Patriotic War.

Step by step, apologetics of the Soviet past, sacralization of the Soviet Union’s Victory in the Great Patriotic War, “historic memory” and “historic truth” are shaping up as a state ideology despite the explicit constitutional ban62. One of the foundations of the Russian constitutional system clearly states that “no ideology shall be established as state or mandatory”. However, this is not the first time (and certainly not the last time) when organs of state power of the Russian Federation infringe upon the foundations of the Russian constitutional system, which they are vigorously protecting from multiple domestic and external enemies with “undesirable organizations.” Moreover, in November of 2022 a new regulation under the title “Foundations of the State Policy for Protection and Strengthening of Traditional Russian Spiritual Moral Values” (approved by presidential decree No 809 of 09 November 2022)63 de facto established a new Russian state ideology in breach of the Russian Constitution. “Protection of traditional Russian spiritual and moral values, culture and historic memory” was proclaimed a strategic national priority. Key goals and tasks of this new ideology include preservation of historic memory, counteractions to attempts of falsification of history, preservation of historic experience of formation of traditional values.

Another foundation of the Russian constitutional system, which is currently in danger, is the principle of supremacy of international law envisaged in Art. 15

(4) of the Russian Constitution: “Universally recognized principles and norms of international law and international treaties of the Russian Federation form a component part of the Russian legal system. If an international treaty of the

Russian Federation fixes other rules than those envisaged by law, the rules of the international treaty shall be applied.” The role of international law in the new democratic Russia was heatedly debated by the Constitutional Assembly of 199364, and even after the 1993 Constitution came into effect, many hard- liners did not welcome the idea of direct penetration of international law into the Russian legal system. The Plenum of the Russian Supreme Court issued two Resolutions65 (No. 8 of 31 October 1995 and No. 5 of 10 October 2003), where it offered the interpretation of Art. 15 (4), which narrowed down the meaning of this constitutional provision and instructed the courts that “only the rules of international treaties of the RF that have entered into force and consent to be bound by which was given in the form of a federal law shall be applied with priority over the laws of the Russian Federation”66. In my view, these Resolutions appear to be an attempt of the Russian Supreme Court both to limit the meaning of provisions of Art 15 (4) only to ratified international treaties of the RF and to restore the elements of the Soviet doctrine of transformation, under which the international obligations of the state would be applicable internally only if they were transformed by the legislature into a separate statute or administrative regulation. By relying on the doctrine of transformation, the Soviet Union was able to sign numerous international treaties, including treaties on human rights, and still avoid implementing some or all of their provisions in the domestic legal order67.

In the early 2010s Valery Zorkin, the Chief Justice of the Russian Constitutional Court pioneered the crusade against the European Court of Human Rights. As a result, in 2015, the Constitutional Court was vested with the power to resolve matters concerning the possibility of enforcing judgements of the ECtHR68. When the constitutional amendments came into effect in 2020, this power was elevated to the constitutional level69. Simultaneously, the Constitutional Court was empowered to decide on the possibility of enforcing judgments of foreign or international (interstate) courts, foreign or international arbitrations, which

impose obligations on Russia, if such judgments contradict the fundamentals of the public legal order of the RF. Compliance with the fundamentals of the public legal order of Russia as a criterion of enforceability is highly problematic for the following reasons: (1) the notion of “public legal order” does not belong to the area of Russian constitutional law, (2) its ambiguity constitutes grounds for arbitrary interpretation, and (3) this vague criterion will make avoiding international obligations of Russia both legal and constitutional70.

The current situation in Russia leaves no doubt that Russia has departed from the Western democratic tradition and replaced it with “traditional Russian values”. The situation with regard to the supremacy of international law doesn’t look better. In February of 2023, Russia withdrew from a number of international treaties including the European Convention on Human Rights of 1950 with Protocols No 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 11, 14, 15, the European Convention on Suppression of Terrorism of 1977, and the European Charter of Local Self- Government of 198571. Generally speaking, the supremacy of law in Putin’s Russia is highly questionable; this statement can be confirmed by the following words of Andrey Klishas, Head of the Committee on Constitutional Legislation of the upper house of the Russian Parliament: “from the political point of view, from the viewpoint of legitimacy, in our country there is no greater authority than the President’s words”72.

Russia’s initial post‑Soviet constitutional design reflected the desire of democratic Russia to become an open and law‑abiding member of the international community. These constitutional provisions, as well as political- legal developments leading to their adoption, demonstrated the expanding role of international law in the building of modern states based on the rule of law73. The enactment of the Federal Law “On International Treaties of the RF” in 1995 was a logical continuation of the constitutionally established principle of the supremacy of international law.

In order to re‑establish the supremacy of international law in Russia, we need to return to the starting point and to repeal a number of constitutional and legislative amendments that undermine or distort the principle of supremacy

of international law. A much bigger task will be to change the attitude of law enforcers, and here we should start from repeal of the aforementioned Resolutions of the Plenum of the Supreme Court. Russian judges will need new guidance, and this guidance should clearly reflect the role of the universally accepted principles and norms of international law.

Equality before the law is a universally recognized fundamental legal principle, which has been established in the Russian Constitution and a number of other legislative acts including the Federal Constitutional Law “On the Judicial System of the RF” of 1996 and the Russian Criminal Code of 1996. Art. 19 (2) in its first part establishes that “the state shall guarantee the equality of human and civil rights and freedoms regardless of sex, race, nationality, language, origin, property and official status, place of residence, attitude to religion, convictions, membership of public associations, or of other circumstances”. Remarkably, the second part of Art. 19 (2), which is the key non‑discrimination clause, is rather narrow: “All forms of limitations of human rights on social, racial, national, language or religious grounds shall be prohibited”74. Such types of discrimination as discrimination on the grounds of political beliefs and sexual orientation have been left behind, and exactly these grounds for discrimination have a strong presence in contemporary Russia.

After numerous unsuccessful attempts to re‑criminalize male same sex relationsinpost‑SovietRussia75,discriminationonthegroundsofsexualorientation obtained legislative entrenchment in 2013, when the new Art. 6.21 of the RF Code of Administrative Offences made “Propaganda of non‑traditional sexual relations among minors” an administrative offence. The new statutory provision became known as “the gay propaganda law”; in 2014, its constitutionality was affirmed by the Russian Constitutional Court in its Resolution No 24‑P76. Notably,

in this resolution the Court stated “as such, adherence to non‑traditional sexual relations may look insulting for many people from the viewpoint of moral norms accepted in the Russian society or otherwise encroaching on public morals and related rights, freedoms and legitimate interests of other persons”77. In 2020, one of Putin’s constitutional amendments envisaged “protection of marriage as a union of a man and a woman»78. This constitutional wording leaves no hope that Russian authorities will form some sort of positive attitude towards same sex marriages79. From this viewpoint, further legislative changes look like a logical continuation. In December of 2022, a set of amendments to the Federal law “On information, informational technologies and protection of information” and other laws addressing the issue of “propaganda of non‑traditional sexual relations/preferences pedophilia and gender reassignment” (which became known as “the LGBT‑propaganda law”) came into effect80. Protection from LGBT- propaganda was extended to all age categories of the population; Art.6.21 of the Code of Administrative Offences was amended accordingly81. Remarkably, the LGBT‑propaganda law treats equally same sex relations and gender reassignment (the activities that may be frowned at by a part of Russian society, but are still legal) and pedophilia (provided that the law doesn’t specify the meaning of this term, so it’s unclear whether it means a psychiatric disorder or sexual relations with minors that constitute a criminal offence»82. The law bans information “that may make children want to get a gender reassignment»83. Owners of websites and web pages are obliged to closely monitor the web in order to spot propaganda of non‑traditional sexual relations/preferences, pedophilia and gender assignment. Similarly, such information shall be banned from mass media, commercials, movies, printed products etc.

Provisions of Russian legislation regulating the status and activities of so- called “foreign agents” (which became known as “the foreign agents law”) offer another example of discriminatory legislation of Putin’s era. The “foreign agents law” was initially advertised by Russian authorities and state‑controlled

media as a Russian version of the U.S. Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) of 1938 despite the striking differences between these two acts.84 The Russian Constitutional Court, which found the “foreign agents law” to be in line with the Russian Constitution, explained in its Resolution No. 10‑P of 08 April 201485 that the notion of a “foreign agent” doesn’t imply “any negative assessment from the part of the state, is not intended to form a negative attitude towards political activities performed by [a Russian NGO designated a foreign agent] and cannot be perceived as a sign of distrust or a desire to discredit such NGO and (or) the goals of its activity”86. However, these statements did not look convincing from the very beginning, and further legislative developments aimed at the “regulation of status of a foreign agent” were openly discriminatory. The Federal Law “On Control Over Activities of Persons Under Foreign Influence” of 14 July 2022 envisages a long list of constraints connected with the status of a foreign agent87, including ban on access to public and municipal services, prohibition against serving as a member of an electoral commission, banning educational activities in relation to minors, a ban against teaching in state and municipal educational institutions etc. More restrictions followed in December of 2022 “in order to improve the regulation of the status of a foreign agent”88,

i.e. declaring a status of a “foreign agent” to constitute grounds for dismissal from a number of state organs. All these new provisions are both discriminatory and unconstitutional. The Constitution explicitly provides that human and civil rights and freedoms can be limited by federal law only to the extent necessary for protection of the constitutional system, morality, health, rights, and legitimate interests of other individuals, ensuring defense of the country and safety of the state89.

More discriminatory legislative provisions followed in 2022 after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The notorious “anti‑fake legislation” is amazingly multi- purpose; it reinstated censorship prohibited by Art. 29 of the Constitution, created a mechanism for aggressive protection of the official version of events in

Ukraine, openly violated freedom of speech and freedom of thought protected by the same Art. 29, constituted additional grounds for discrimination on the grounds of political beliefs and prosecution of dissent. Disproportionally severe punishments envisaged in new pieces of the “Special Military Operation” legislation were intended to deter both the opponents of the regime and those who are still undecided. The severe sentences imposed on Ilya Yashin and Alexey Gorinov, the pending case of Vladimir Kara‑Murza and many others are supposed both to punish opposition politicians and critics and to instruct the general public to refrain from criticism and nonsupportive comments regarding the situation in Ukraine and Russian foreign and domestic policy in general.

Truth be told, such disproportionally severe punishments have become a recognizable feature of the Russian system of criminal justice. It would be no exaggeration to say that a rational and proportionate approach to punishment has almost disappeared in today’s Russia. Numerous law enforcement decisions, including those made in the so‑called “Moscow Case” of 2019, display the worst attitudes of Soviet criminal law, namely, the disproportionate severity of sentences and the obvious pro‑prosecution bias on the part of judges. On September 16, 2019, the actor Pavel Ustinov was sentenced to three and a half years in prison for allegedly dislocating the shoulder of a police officer during a demonstration that happened on August 3rd. In response to the allegations, Ustinov said that he was not participating in the rally and that he did nothing to resist the police officer. Judge Alexey Krivoruchko from the Tverskoy district court of Moscow refused to consider videos of Ustinov’s detention (that seem to support his story and show that the police officer was not injured) as an item of evidence90. The case of financial manager Vladislav Sinitza provides us with another example of the disproportionate severity of punishment. On September 3rd, 2019, he was sentenced to five years in a standard regime penal colony for a Tweet. In the Tweet, Sinitza expressed his doubts as to whether the kids of force structure officers would get home safely after the brutal suppression of the non‑coordinated protest rally of July 27, 2019. The court aligned with the prosecution and ruled that Sinitza’s Tweet contained an incitement to violence against the children of policemen91 and members of Rosgvardiya92. In September 2022, the Russian

journalist Ivan Safronov was sentenced to 22 years in a strict regime prison colony for committing high treason. The internationally established purposes of criminal punishment93 are to: a) restore social justice; b) to punish the convict; and c) to deter other crimes. The Russian criminal justice system has so far largely focused on the third part, whereas the first two elements are apparently ignored. Disproportionately severe punishments (as in the cases of Konstantin Kotov (who was convicted under Art. 212.1 of the Criminal Code, Vladislav Sinitza and many others) are intended to terrify the “offenders” and to scare away their potential followers.

Today Russia needs judicial reform even more than in 1991, when the Concept of Judicial Reform of October 24,1991 was approved. This Concept was a fundamental document symbolizing the start of considerable modifications in the judiciary, especially targeting the transformation of Soviet courts into an independent branch of power. The mission of the reformers was to create conditions for implementation of the principle of decisional independence, which had been envisaged on a constitutional level since 193694 but had no chance to be enforced under the totalitarian regime.

Judicial independence is a central component of any democracy and is crucial to the separation of powers, the rule of law, and human rights95. The institutional independence of courts and the individual independence of judges during the process of reviewing the facts of the case, conducting legal analysis, and deciding in a case are deeply interconnected. As a practical matter, it is nearly impossible to separate the conditions that threaten the institutional independence of the judiciary and the independence of individual judges in their official capacity96. According to Judge Birtles, judicial independence

is composed of two foundations. Only together do the two guarantee the independence of the judiciary. These two foundations are the independence of the individual judge and the independence of the judicial branch97. As Elena Abrosimova puts it, both drafters of international acts and Russian lawmakers highlight the togetherness of the institutional independence of courts and the decisional independence of judges98.

Normative entrenchment of institutional independence of courts was a much easier task. The 1993 Constitution of Russia proclaimed the independence of the Russian judiciary (arts. 10, 118, etc.), basic principles of organization and operation of courts including judicial independence, administration of justice only by courts, prohibition of extraordinary courts, adversarial procedure and publicity of court proceedings, financing of courts from the federal budget, fundamentals of legal status of judges – independence, irrevocability, inviolability (art. 118–123) and established the RF Constitutional Court, the RF Supreme Court, the Higher Arbitrazh Court, federal and other courts (art. 125–128)”99. The Laws on Arbitrazh Courts and the Constitutional Court were adopted in July of 1991, the Law on the Status of Judges in 1992, and the Federal Constitutional Law “On the Judicial System of the RF” followed in 1996. By that time, the institutional design of the Russian judiciary looked very impressive, and numerous constitutional and legislative provisions addressed the issue of independence of the judicial branch. Ensuring the due level of decisional independence of judges turned out to be a real challenge, since this task needed to be completed while taking into account the strong influence of the Soviet past.

Russian lawyers have only very recently begun to recognize the tremendous importance of path dependence. Factors from the Soviet past that still affect Russian courts today due to path dependence can be divided into three groups. External Factors (group No 1) include, in the first place, the fact that under Soviet rule courts did not constitute an independent branch of power. This is not surprising, since the principle of the separation of powers was not compatible with the totalitarian regime that existed in the USSR. Strong dependence upon the Communist Party constituted another external factor. For judges‑to-be, membership in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

(CPSU) was a condition sine qua non. Directives of the CPSU bodies were fully mandatory for judges and had to be executed immediately. Dependence upon administrative agencies was factor No 3, which primarily related to financial and social issues. In the USSR, judges were one of the most poorly paid positions in the legal profession, so material support, social services, and social benefits for judges had great importance. Also, in certain periods under Soviet rule (especially under Joseph Stalin), the courts were nothing but an element of an enormous repressive machine used for the destruction of life and altering the destinies of millions of people. The courts, both de jure and de facto, were a part of a unified law enforcement system, which ensured that judges depended upon the CPSU bodies, administrative agencies, the USSR Ministry of Justice (to which the courts were subordinated), and the prosecutors. Internal Factors (group No 2) embraced dependence upon chairpersons of the courts, who played and still play the main role in exercising influence on judges, since court chairpersons enjoy a remarkably wide scope of powers. Factor No 2 was the existing system of the administration of courts and the judicial community (i.e. Judicial Councils, Qualification Commissions and Self‑Governing Bodies), which is used to exercise influence on the content of judgments and the procedures for decision‑making. Dependence upon higher courts, especially the Russian Supreme Court, constituted the internal factor No. 3100. This problem is especially important due to a great number of resolutions or instructions issued by the Supreme Court. These acts are usually intended to instruct the lower courts how to apply norms of a certain legislative act, and which circumstances must be taken into consideration when handling criminal or civil cases. Another purpose of these acts is to ensure the so‑called “uniformity of court practice”. In reality, maintenance of uniformity of court practice translated into imposition of considerable limitations on judicial discretion and decisional independence of judges101.

The specific mentality of the Soviet judges, which is usually referred to as the “Soviet judicial mentality”, constitutes the third group. The Soviet judicial mentality turned out to be amazingly sustainable: three decades after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Soviet judicial mentality is still persistent. It became slightly different, and acquired several new qualities, but, by and large, preserved its Soviet nature. The first important feature of the Soviet judicial mentality is the specific self‑identification of Soviet judges, who never felt like

independent arbitrators vested with the power of administration of justice. On the contrary, they self‑identified themselves as governmental officials and acted like governmental officials. They were sure that their main goal was to protect the interests of the Soviet state. The impact of their previous career comes next; most Soviet judges were former prosecutors, law enforcement officers, or secretaries of judges, who themselves had been on the bench since the Soviet period102. No wonder that these former prosecutors, investigators and other law enforcers applied old familiar behavioral patterns to the administration of justice. Defense attorneys almost never had a chance to become judges. They were more autonomous than the representatives of other branches of the legal profession, so the system considered them unreliable and somewhat suspicious. This type of selection of prospective judges actively contributed to shaping another salient feature of the Soviet judicial mentality: an accusatory or prosecutorial bias. Most Soviet judges felt obliged to issue guilty verdicts. Usually, the text of the indictment served as a rough draft of the verdict. If a judge took the risk of delivering an acquittal, s(he) usually had to present two explanatory notes: one to the court chairperson and the other to the local organization of the Communist party. Professional deformation of judges constitutes another essential feature of the Soviet judicial mentality. After becoming members of the judicial corporation, the new Soviet judges had to promptly adjust to the rules of the game. These rules included unconditional subordination to the chairpersons of their courts, and following the instructions of the upper courts, Communist Party bodies, officials of administrative agencies, and other outside actors. Quite soon, the new Soviet judges started to feel that they also were governmental officials. While handing down verdicts, they were guided not only by the provisions of the legislation in force, but even more by the acts of administrative agencies, not to mention the phenomenon of “telephone justice”. There was no need for independent and impartial judges. On the contrary, good Soviet judges had to be obedient and easily manipulated103. Presumption of innocence was treated as a foreign concept under the Soviet rule; only in 1977 was it partially envisaged on the constitutional level104 and then it was replicated in the 1960 Criminal Procedural Code of RSFSR105. However, the language in both lacked

the key component of presumption of innocence: innocent until proven guilty. The full‑fledged definition of presumption of innocence was established on the constitutional level in post‑Soviet Russia in December of 1993106.

“It is fundamental to the Rule of Law that the system of appointment of the Judiciary should guarantee the Judiciary’s independence from influence by the Executive or the Legislature. Even more important is the requirement that the Judiciary, once appointed, should be free from any threat of removal or other form of intimidation from the other arms of government. Respect for the Rule of Law requires that there be independent, transparent mechanisms for the removal of judicial officers found guilty of misconduct, but it is essential that such mechanisms are beyond manipulation by other arms of government and do not undermine the independence of the judiciary107.” Sadly, the current situation with judicial appointments and removals in Russia is profoundly at odds with this statement.

For a number of years, the President has had the final say in all judicial appointments in Russia. The Modus Operandi of numerous Russian judges demonstrated in the span of the last two decades sends a warning signal that in the current system of judicial appointments loyalty is valued above professionalism. Many recent judgments and examples of judicial behavior displayed in a number of high‑profile cases raise reasonable concerns that numerous Russian judges are wholly unsuited to the office due to presence (or absence) of certain salient features that are necessary for a good judge.

A merit‑based system of judicial appointments must be introduced in the first place. Procedures for psychological and personality testing for candidates for judicial positions in the current regulatory framework must be significantly improved. The Modus Operandi of Russian judges proves that the Methodological Recommendations for Organization of Psychological Support of Selection of Judicial Candidates approved by the Judicial Department of the

Russian Supreme Court108 are obviously insufficient. Under these Methodological Recommendations, the purpose of psychological and personality testing of candidates for judicial positions is to get a comprehensive and reliable description of individual psychological characteristics of a candidate. Results of such testing shall be directed to the Qualification Collegium of Judges; after that the candidate will be entitled to get acquainted with these results as well as with other materials from her personal file. The package of qualities of judges‑to-be includes both the professional level of a candidate and a number of psychological characteristics and personality features. In the absence of any assessment of such characteristics and features, it is impossible to predict how successful the candidates will be in their future professional activities and whether they’ll make good judges. The necessity of a psychological evaluation of candidates for judicial positions is warranted by:

Moreover, for certain professions, including the judicial profession, successful performance of an employee directly depends upon certain psychological features of such employee110. Psychological and personality testing is a sine qua non for judges‑to-be — especially in Russia and other post‑Soviet states, which are still strongly affected by the Soviet legacy, and where the phenomenon of the Soviet judicial mentality is still present.

In my view, Russia has reached the point where the possibility of lustration of judges should be considered. Foremost Judges From Arbitrazh Courts, psychological evaluation may be enough. Judges who adjudicate politically motivated cases

are mostly judges from general courts. Drafting of a comprehensive lustration law shall be a separate and challenging tack. The negative experience of two Ukrainian lustration laws should be taken into account. Also, recommendations of the Venice Commission issued in its Interim opinion on the Lustration law of Ukraine of 12–13 December 2014 should be analyzed, and the following four key criteria that summarize the essence of the international standards pertaining to lustration procedures should be used in the course of drafting of a Russian lustration law:

Judicial reform cannot be successful if it is performed in isolation; it must come as a part of a comprehensive reform program. Transformation of the institutions connected with the judiciary (such as investigation, procuracy, police etc) must be performed simultaneously with judicial reform. In emerging democracies trying to depart from their authoritarian past, it is vital for the legitimacy of the state that police‑citizen interactions are compatible with the values of a democratic society112. In the transitional period, the militia (which is usually renamed and is referred to as “police”) acquires a crucial role. First, the actions of the police will have a bearing on the success or failure of nascent democratic institutions. Police can either help or dramatically hinder processes critical to democracy, including voting, speaking in public, publishing, assembling, voicing opposition, and participating freely in the politics of the state.113 The actions of the police can strongly influence the success of emerging democratic institutions114. A duly trained police service can maintain stability during the turbulent time of

transition and “play an important role during those periods of uncertainty that are notorious for the accompanying problems of public and political disorder, crime and violence, and poverty and disorientation of the population.” Being the most visible arm of state authority, police can provide a valuable demonstration of the character of the new society. If citizens have repeated interactions with courteous, professional police, they may gain increased confidence in and lend support to their new government115.

When reforming a repressive militia force structure in the context of a new democracy, the end‑goal is the creation of a civilian democratic police service116. There are various definitions of what constitutes a civilian democratic police, but two common ideas are that a democratic service is one that is both “downwardly responsive” and accountable117. The fundamental difference is the following: a downwardly responsive service is one that responds “down” to the needs of citizens, rather than “up” to the demands of the state118. A “downwardly responsive” service must be accountable to elected, civilian authorities, rather than a shadowy security structure. Further, civilian democratic police must also be accountable to the public, through media, civilian groups, NGO’s, complaints boards, and the like119. That is the only way to transform a repressive police force, which protects the state from its citizens, into a police service that works for the people120. Like any other reform, the police reform cannot be conducted outside of other reforms of the criminal justice sector, and the success of police reform strongly depends on the efficiency of transformation of other institutions connected or interacting with police. Nevertheless, the centrality of police reform cannot be over‑emphasized121. An undemocratic state can have a civilian democratic police force; but a legitimate democracy cannot exist with a non- responsive, unaccountable, authoritarian police force, which works against the people and not for the people122.

Under Putin’s rule, numerous legislative changes came to life as a part of the trend of escalation of authoritarianism, witch‑hunts and prosecution of dissent. Most of these new norms undermine, infringe upon, or repeal the democratic achievements of the 1990s, when judicial reform and legal reform were going at full steam.

This section provides the list of the most important changes in the Russia regulatory framework that must be made ASAP in order to ensure the solid establishment of the Rule of Law. This list is not exhaustive; it includes the most urgent alterations that are vitally important for re‑establishing democracy in Russia.

The following legislative provisions must be repealed as totally incompatible with the goal of establishing the Rule of Law in Russia.

“Foreign agents legislation” (amendments to Federal Laws “On NGOs” and “On Public Associations”, “On Information, Information Technologies and Protection of Information”, “On Mass Media”, “On Enforcement Actions Against Persons Involved in Violations of Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms, Rights and Freedoms of citizens of the Russian Federation”. Federal Law “On Control Over Activities of Persons Under Foreign Influence” of 14 July 2022. Federal Law of 05 December 2022 N 498- FZ123 (the most recent amendments to Federal Laws “On Banks and Banking Activities”, “On Mass Media”, “On the Procuracy of the RF”, “On State Secrets”, “On Federal Security Service”, “On Public Associations”, “On State Support Of Youth and Children’s Public Associations”, “On NGOs”, “On Foreign Intelligence Service”, “On Service in the Customs Service of the RF”, “On Vital Records”, “On Status of Military Servants”, “On Political Parties”, “On Counter‑Actions to Legalization (Laundering) of Illegally Received Income and Financing of Terrorism”, “On Main Guarantees of Electoral Rights and Rights to Participate in Referendum of Citizens of the RF”, “On Elections of the President of the RF”, “On the System of Public Service of the RF”, “On Insurance of Deposits in Banks of the RF”, “On Assemblies, Rallies, Demonstrations, Processions and Pickets”, “On Public Civil Service of the RF”, “On Information, Information Technologies and Protection of Information”, “On Municipal Service in the RF”, “On the Order of Making Foreign Investments into Economic Entities Possessing Strategical Importance for Ensuring Defense of

the Country and Safety of the State”, “On Public Control Over Protection of Human Rights in Detention Facilities and Assistance to Persons Kept in Detention Facilities”, “On Anti‑Corruption Expertise of Normative Legal Acts and Drafts of Normative Legal Acts”, “On Protection of Children From Information Detrimental for their Health and Development”, “On Purchase of Goods, Works, Services by Certain Types of Legal Entities”, “On Service in Internal Affairs Bodies of the RF and Making Changes to Certain Legislative Acts of the RF”, “On Accounting”, “On Education in the RF”, “On the Contract System in the Sphere of Procurement of Goods, Works, Services for Provisioning Governmental and Municipal Needs”, “On Election of Members of the State Duma of the Federal Assembly of the RF”, “On Service in the Correctional System of the RF…”, “On Service in the Enforcement Agencies of the RF…”, “On State (Municipal) Social Procurement for rendering State (Municipal) Services in Social Sphere”, “On State Control (Supervision) and Municipal Control in the RF”, “On Control over Activities of Persons Under Foreign Influence”.

Legislative provisions on “undesirable organizations” including Art. 3.1. of Federal Law “On Enforcement Actions for Individuals Involved in Violation of Fundamental Human and Civil Rights and Freedoms” of 2012, Art. 284.1 “Performing activities of a foreign or international NGO, which activities of the territory of the Russian Federation have been recognized as “Undesirable”, Art.

20.33 of the RF Code of Administrative Offences.

“LGBT propaganda legislation” (relevant legislative provisions listed in Federal Law No 478‑FZ of 05 December 2022)

A number of activities, which were criminalized or made administrative offences as a part of Putin’s witch‑hunts, should be removed from the Russian Criminal Code and the Russian Code of Administrative Offences. The following articles of the Criminal Code must be repealed as the first order of business: Art. 212.1 “Repeated violations of the established rules of organizing or holding public gatherings, meetings, rallies, marches, and pickets”, Art. 330.1 “Avoiding fulfillment of responsibilities envisaged by the RF legislation on foreign agents”, Art. 354.1 “Rehabilitation of Nazism”, Art. 280.1 “Public calls for conducting activities aimed at violation of territorial integrity of the RF”. Art. 275 “High treason” must be restored in its initial wording. The “Special Military Operation” legislation shall be repealed in full as totally incompatible with the goal of establishing the Rule of Law.

“Foundations of state policy on the preservation and strengthening of

Russia’s traditional spiritual and moral values”124 of 09 November 2022 — must be repealed as establishing the state ideology of Russia in breach of explicit constitutional prohibition envisaged in Art. 13 of Chapter 1 “Fundamentals of the constitutional system of the Russian Federation” of the Russian Constitution.

Legislative changes that were announced as an effort to bring the existing legislative framework in line with the amended Constitution. Some of these changes stepped far beyond the new constitutional design and had nothing to do with the amendment of a number Russian laws in order to bring them into conformity with the constitutional amendments‑2020. The negative effect of such legislative changes can be compared to that of the constitutional amendments‑2020. Changes made125 to the Federal Constitutional Law on the Constitutional Court of the RF can serve as a perfect example and must be discussed in greater detail. New provisions of this FCL modified the procedure of the official explanation by the Constitutional Court of its previous resolutions and opinions. The initial version of Art. 83 provided that the question concerning the explanation of the resolution of the CC RF shall be considered in the session of the CC RF under the procedure in which this resolution was adopted. Pursuant to the amended version, the open procedure is no longer available, and the question of explanation of a resolution/opinion of the CC RF shall be handled in camera. Only Justices and court employees in charge of minutes‑keeping and maintenance of deliberations running normally can be present in the chambers. The minutes shall be signed by all Justices, who were in attendance. The minutes are not subject to disclosure; justices and other persons who were in attendance cannot divulge the nature of discussion and the results of voting. Parties to the case are no longer eligible to participate in such proceedings. Under the new wording of Art. 83, the copy of the request must be sent to the parties with the invitation to comment in writing within a fixed period of time on the question raised in the request for official explanation. Exceptions can be made for the cases when an official explanation is urgent and cannot wait. Clearly, this new procedure allows the revisiting and secretly changing most previous judgments of the Russian Constitutional Court in the absence of open procedures and without participation of the parties to a case. In so doing, important and universally binding legal positions of the Constitutional Court can be easily repealed for political reasons – exactly like it happened on December 24, 2020. On that day the Constitutional Court delivered the official

explanation126 of its landmark Resolution No 8‑P of 27 March 2012127, where it (without expressly saying so) effectively overruled the Constitutional Court’s prior legal positions regarding the Russian Constitution and the 1995 Federal Law on the International Treaties of the RF, which were stated in previous cases including Resolution No. 8‑P. It deserves mention that the Resolution No 8‑P was one of the key legal sources in the appellate proceedings on YUKOS shareholders vs Russia in the Hague Court of Appeal.

The amended Art. 76128 the FCL on the CC RF places a ban on publication of dissenting opinions by Justices of the Constitutional Court. Now written dissenting opinions of Justices shall be attached to the minutes of the session of the Court and kept together with it. Justices cannot publish any opinion in any form or publicly refer to it. Other amendments impose additional constraints on Justices of the CC RF, who cannot express their opinion on the matter which may be subject to consideration by the CC RF, as well as the one which is currently under consideration or has been admitted for consideration by the CC RF until the decision on the matter has been handed down in the following forms:

Justices of the CC RF are also strictly prohibited from criticizing judgments of the CC RF in any form129.

As we see, none of these new rules were mentioned in the constitutional amendments‑2020. However, they appeared as a part of the process of bringing the Russian legislative framework in line with the amended Constitution and significantly affected the constitutional review landscape in the most negative and disruptive way.

Obscure and ambiguous language in numerous Russian laws adopted in the span of the last two decades has become a recognizable hallmark of Russian law‑making. One of the best examples can be provided by the amended wording of Art. 275 “High Treason” of the Russian Criminal Code of 1996, which defines high treason as an act “that is committed by a citizen of the Russian Federation, acts of espionage, disclosure to a foreign state, an international or foreign organization, or their representatives of information constituting a state secret that has been entrusted or has become known to that person through service, work, study or in other cases determined by the legislation of the Russian Federation, or any financial, material and technical, consultative or other assistance to a foreign state, an international or foreign organization, or their representatives in activities against the security of the Russian Federation.”130

The following are the most dangerous pitfalls of the new wording of Article 275 of the Criminal Code of Russia. First, the phrase “hostile actions to the detriment of the external security of the Russian Federation” is replaced by the ambiguous phrase “activities against the security of the Russian Federation.” The omission of the word “hostile” essentially makes this concept extremely ambiguous. Second, it is obvious that by the legislation’s design, the new definition covers not only external but also internal security. A clear and detailed definition of both concepts is absent from the Criminal Code. Third, ambiguity of the wording “financial, material and technical, consultative or other assistance to a foreign state, an international or foreign organization, or their representatives in activities against the security of the Russian Federation” makes it applicable to almost any activity. Fourth, international organizations are identified as potential recipients of information constituting state secrets, as well as of the abovementioned types of assistance. Any list of such recipients must necessarily be open‑ended and can include any international organization by default. Sixth, the vagueness of this statutory provision makes it impossible for citizens to properly abide by it, a violation of one of the fundamental conditions of the rule of law. This ambiguity creates unlimited possibilities for arbitrary interpretation and selective application. Pursuant to the provisions of Article

275, a criminal case for high treason can be initiated against any citizen of the Russian Federation who provides someone almost any information or commits almost any action. In other words, under the new wording of Art. 275, providing almost any information and committing almost any act by any Russian citizen may be qualified as high treason. These flexible provisions suggest parallels with early Soviet criminal law131.

Apparently, this approach to the language of legislative and regulatory acts and judicial decisions was not invented by Putin’s lawmakers — it was borrowed from the early Bolshevik acts. That’s how the head of Soviet Russia Vladimir Lenin outlined the role of judges in a letter to People’s Commissar of Justice D. Kurskiy: “the courts should not do away with terror — to promise that would be to deceive ourselves and others — but should give it foundation and legality, clearly, honestly, without embellishments. Formulations must be as wide as possible”132. Language of a number of early Bolshevik acts was remarkably vague. In early Soviet criminal legislation, the juridical categories of crime, punishment, and guilt were replaced by sociological categories. The phrases “socially dangerous act” and “measure of social defense” were substituted for such fundamental categories as “crime” and “punishment”133. This was done in order to give the Soviet judges flexibility in adjudicating criminal cases and convicting those whom the regime wanted to be convicted and punished. Taken together with the infamous Art. 24 from the Decree On People’s Courts of the RSFSR of 30 November 1918 (“People’s Courts are not bound by any formal evidence, and depending on the circumstances of the case, it is up to the court to allow certain evidence or request such evidence from a third person, for whom such requests are mandatory”134), these normative and non‑normative wordings created grounds for unlimited judicial discretion and selective application of law, which later became symbolic of Russia and the Soviet Union.

Whereas such vague language of early Bolshevik regulations served its clearly intended goal, presence of such “rubber norms” in the legislative framework of the country, which made the Rule of Law one of the fundamentals

of its constitutional system135, is totally unacceptable. Legal certainty, i.e. accessibility and clarity of legislative acts, is one of the essential elements of the Rule of Law. Precise and explicit language constitutes the key feature of such legislative acts and makes the content of these acts accessible for everyone. That is the only way to ensure that people will duly obey the requirements of the law. Addressees of legal norms can obey the laws only if the content of the norms is sufficiently clear and understandable. In order to make the laws clear, the lawmakers must use precise definitions and avoid loose phraseology. Availability of explicit language and definitions in legislation constitutes a guarantee that juridical facts, which implicate legal consequences, shall be determined by laws, and not by those who enforce such laws136.