Political Repressions in Russia in 2021

2021 saw widespread political repressions across Russia

By Anton Mikhalchuk August 27, 2021

2021 saw widespread political repressions across Russia

By Anton Mikhalchuk August 27, 2021

2021 saw widespread political repressions across Russia. On January 17, 2021, opposition leader Alexei Navalny returned to Russia where he was immediately arrested at the airport on charges related to the “Yves Rocher case,” for which he had previously received a suspended sentence. Two days after his arrest, a film was released about Putin's alleged palace in Krasnodar Krai worth $1.35 billion.[1]

On January 23, protests were held against the arrest of Navalny in 198 cities. According to the head of the regional headquarters of the Anti‑Corruption Foundation, they were attended by up to 300,000 people across the country.[2] During the protests, police beat the participants, and 4,033 people were detained by the police, about 300 of whom were teenagers. Throughout the next eight days, protests were held in 121 cities and resulted in detention of 5,754 people. On the day of Navalny's trial on February 2, police detained another 1,463 protestors, 1,188 of them in Moscow. Between January 23‑February 2, more than 11,000 people were detained.

The overwhelming majority of those detained were convicted under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offenses, which provides punishment for participating and organizing protests without permission. The article establishes fines (from $130 to $4,000) or arrests up to 30 days. Because there is not enough space in Moscow to accommodate such a large number of arrested people, protesters were taken to the Foreign Citizen Temporary Detention Center in the village of Sakharovo, just outside Moscow. The center held about 800 protestors at a time and was unprepared to house so many people. On the night of February 2, 200 people were brought to Sakharovo and were each processed for 20 minutes. People spent hours in cold paddy wagons without access to toilets, food, or water. Some of those arrested weren’t able to eat for 40 hours.

Conditions in Sakharov were also torture. The cells, with capacity to hold eight people, held up to 27 people at a time. The cell toilets were holes in the floor and were not partitioned off. A significant number of those arrested did not receive mattresses and were forced to sleep on the floor.

After the protests between January 23rd‑February 2nd, 90 criminal cases were initiated. People were charged with incitement to riot (Part 3 of Article 212 of the Russian Criminal Code), involvement of teenagers in illegal actions (Part 2 of Article 151.2) and attacks on police officers (Article 318).

In several regions, criminal cases were brought against activists for blocking the roads under Part 1 of Article 267, which permits up to one year of imprisonment for those convicted. Dozens of activists have been questioned in these cases and searches have been carried out. In Moscow, the libertarian Gleb Maryasov has been charged under this criminal article. Similar criminal cases were brought against nine people in Chelyabinsk, nine in Vladivostok, and one in Izhevsk. A case under Article 267 was also opened in St. Petersburg, though no one has been accused yet.

On January 24, the day after the first protest for Navalny’s release, a criminal case was initiated under Part 1 of Article 236, “Violation of sanitary and epidemiological standards,” which allows for up to two years in prison. The investigators insist that the rally on January 23rd endangered the lives of its participants due to the risk of spreading COVID‑19. Ten Russian opposition politicians were accused: municipal deputies Dmitry Baranovsky, Lyudmila Stein, and Konstantinas Jankauskas; member of the punk rock and performance art group Pussy Riot, Maria Alyokhina; leader of the independent trade union Doctors’ Alliance, Anastasia Vasilyeva; and Navalny’s associates Nikolai Lyaskin, Oleg Stepanov, Lyubov Sobol and Kira Yarmysh, as well as his brother Oleg Navalny.

On July 14th, 2021, the case against Jankauskas was dropped. At the moment, the freedom of movement for Oleg Navalny, Yarmysh and Stein is restricted; the rest of the accused are under house arrest.

A similar charge was brought against two people in Nizhny Novgorod.

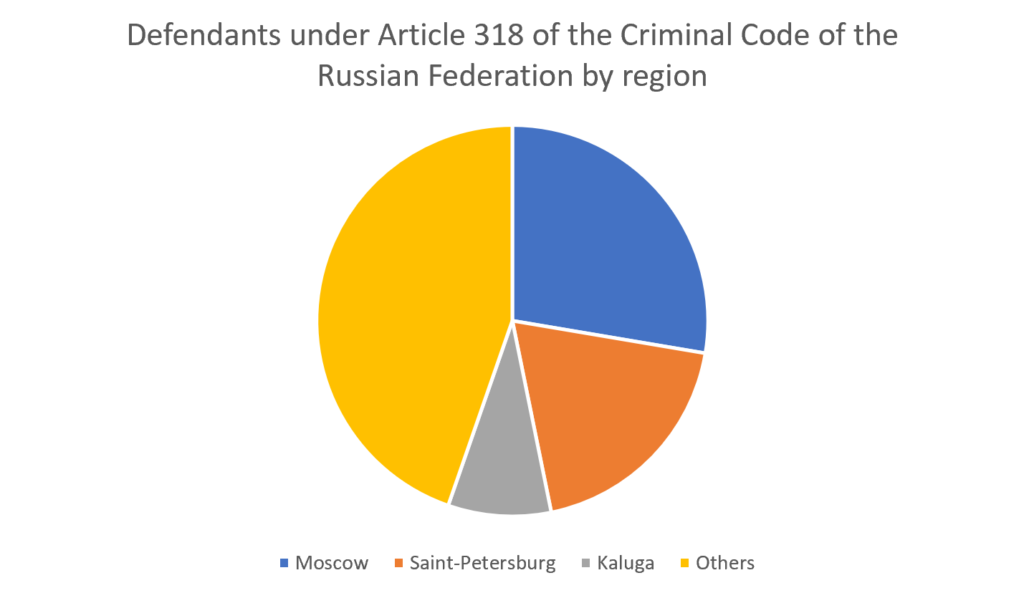

The most common criminal charge after the protests was for attacking government officials under Parts 1 and 2 of Article 318. The consequence of this charge can be up to 10 years in prison. Not a single case was brought against police for using unjustified violence despite the abundance of documentary evidence.

In Moscow, under this article, a case was brought against 13 people: one person was sentenced to three and a half years in prison, three were sentenced to two years in prison, one to one year in prison, and another was convicted, conditionally. The rest of the trials continue, and some of the accused remain in jail.

In St. Petersburg, nine people were accused of attacking the police: three received suspended sentences, and for the rest, the trials are ongoing.

Across other regions, 21 cases were brought against the protesters under Article 318. As of August 2021, there has not been a single acquittal. It is interesting that only ordinary participants have been charged under this article.

A number of protesters on January 23rd were accused of hooliganism under Article 213—this charge can result in up to seven years in prison. Protestors have been accused on video of throwing snowballs at police officers, beating other people, and damaging city infrastructure. At the moment, seven people have been charged under this article.

Nine people were accused of calling for protests on social media platforms under Article 212.3, which permits up to two years of imprisonment. Two people were sentenced to one year and six months, respectively, while the rest are under investigation. In all cases, the charges are related to publications on the platforms, VKontakte (VK) and Telegram.

In Primorsky Krai, Penza, Kazan, Vladimir, Novosibirsk, and Tula, seven people have been accused of inciting violence under Article 280 and face up to five years in prison. All cases are related to posts on social media platforms.

Across six regions in Russia, activists have been accused of vandalism. The cases are a reaction to graffiti on walls and monuments: “Putin is a thief!” (in Tomsk), “Putin is a thief and a murderer!” (in St. Petersburg), “Putin, go away” (in Yuzhno‑Sakhalinsk), and “Freedom for Navalny!” (in Vladivostok). The content of the graffiti in Vologda was obscene. These cases were brought under Article 214 and can result in up to three years in prison.

Three people have been accused under Article 212.1 for repeated violation of the rules for participation in protests and face up to two years in prison. These cases are a consequence of protests in support of the arrested governor of Khabarovsk Krai, Sergei Furgal.

After January 23rd, criminal cases were also brought against protestors on the charges of insulting a government official in St. Petersburg, destruction of property in Moscow, and false reporting of a terrorist attack in Belgorod. The case in Belgorod is the most absurd—the activist was accused of posting a comment, “It’s the bomb!” under the post about the January 23 rally in support of Alexei Navalny in a closed group on a social media platform VKontakte.

On April 21st, a second set of protests were held in support of Alexei Navalny. His Headquarters coordinator Leonid Volkov said he would announce a protest after half a million people registered as participants on the organization’s site. After Navalny went on a hunger strike in prison, it was decided to hold the protest ahead of schedule. Rallies were held in 109 cities and resulted in the detaining of 2,096 people, almost half of whom were in St. Petersburg. There were few arrests in Moscow—only 35. Some of the detainees were arrested and held for up to 15 days.

The coordinator of Navalny's headquarters in Primorsky Krai, Andrei Borovikov, was accused of publishing pornographic materials. He made reposted a clip of the band Rammstein performing its song, “Pussy,” on his VK page. On July 15th, he was sentenced to two years and three months in prison. This clip has been published thousands of times by other users without repercussion.

In October 2020, Pavel Zelensky, videographer of the Anti‑Corruption Foundation, posted a tweet accusing the authorities of driving Nizhny Novgorod activist Irina Slavina to suicide. For this tweet, he was taken into custody on April 16th, 2021, and was charged with public appeals to extremism under Article 280.2. Zelensky is currently serving a two‑year sentence prison.

A number of candidates were rejected after applying to participate in the State Duma elections. A criminal case was brought against Moscow District Deputy Ketevan Kharaidze, and Ilya Yashin was banned from participating in the elections. A number of activists left the country fearing for their safety .

Andrei Pivovarov, the chairman of the public movement Open Russia, was also subjected to repression. After the dissolution of the organization, he was removed from a Moscow‑Warsaw flight and detained in June 2021. A criminal case was brought against him under Article 284.1 for participating in the activities of an undesirable organization. Pivovarov is currently in custody.

Four editors of the DOXA student magazine of the Higher School of Economics have been accused of supporting the protests in Russia. Criminal cases were brought against them under Articles 151.2 (involvement of teenagers in dangerous actions) and 298.1 (libel). All four are currently under house arrest.

On May 19th, 2021, the candidate for the State Duma from the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, Nikolai Platoshkin Ph.D., was sentenced to five years of suspended sentence for publicly disseminating false information about COVID‑19 and calling for riots. Platoshkin, during his communication with subscribers on social media platforms, reported that Moscow hospitals weren’t able to cope with the large number of patients—he did not publish any calls for riots. The case is politically motivated, and Platoshkin is barred from participating in the State Duma elections.

In March 2019 in the capital of Ingushetia, Magas, protests were held against the ceding of part of the republic's territory to Chechnya. During the protests, criminal cases were brought against 51 protesters. In 2021, four participants were convicted, and an investigation was initiated against two more.

In 2021, more than 100 politically motivated criminal cases were brought against protestors, and around 13 thousand people were convicted for participating in protests. The number of people who left the country cannot be counted.

[1]Alexei Navalny, “Palace for Putin. The history of the biggest bribe,” accessed August 19, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ipAnwilMncI.

[2]Наталия Зотова, Оксана Чиж, и Владимир Дергачев, “’Спичка в сухой траве.’ Почему протестуют российские регионы и что будет дальше,” BBC, accessed August 19, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/russian/features‑55893117.

[3]Data is taken from Memorial, accessed August 19, 2021, https://memohrc.org/ru/pzk‑list.

The main political event in Russia in 2021 was the elections to the State Duma, or the lower house of parliament. On the one hand, the elections brought closure to the long period of preparation for them; on the other hand, they signified the onset of a new period in the development of Russia’s political system

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

December 22, 2021

Article

Article It is hard to summarize dispassionately the results of the outgoing year 2021 – it turned out to be just too turbulent. And this turbulence did not let up for even a second, even in the days running up to New Year’s Eve

By Vladimir Milov

December 29, 2021

Article

Article Putin's annual press conference upheld his long‑standing tradition: no matter what topic the Russian president attempted to discuss, his narratives are full of fakes, disconnected from reality and inevitably swerve into anti‑Western tirades

By Yury Krylov

December 23, 2021

The main political event in Russia in 2021 was the elections to the State Duma, or the lower house of parliament. On the one hand, the elections brought closure to the long period of preparation for them; on the other hand, they signified the onset of a new period in the development of Russia’s political system

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

December 22, 2021

Article

Article It is hard to summarize dispassionately the results of the outgoing year 2021 – it turned out to be just too turbulent. And this turbulence did not let up for even a second, even in the days running up to New Year’s Eve

By Vladimir Milov

December 29, 2021

Article

Article Putin's annual press conference upheld his long‑standing tradition: no matter what topic the Russian president attempted to discuss, his narratives are full of fakes, disconnected from reality and inevitably swerve into anti‑Western tirades

By Yury Krylov

December 23, 2021