Russia’s Liberal Party of the Future

Prospects and weaknesses

By Fedor Krasheninnikov February 06, 2025

Prospects and weaknesses

By Fedor Krasheninnikov February 06, 2025

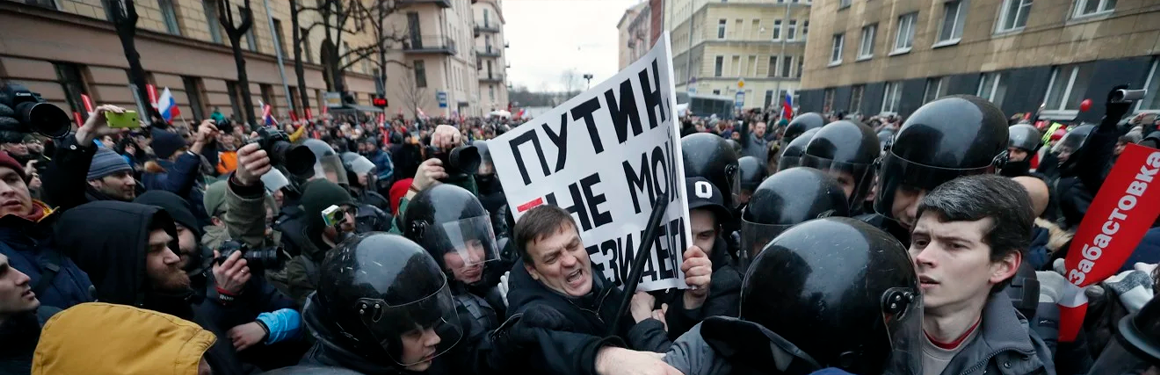

The Kremlin bundles all of Putin’s critics as the “liberal opposition,“ sparing no scorn for the critics themselves, liberalism as a philosophy, or its particular values.

Some opposition figures wear the label of liberal with pride, while others refuse to be labeled as such. At the same time, each side interprets liberalism and liberals in entirely different ways.

The Kremlin bundles all of Putin’s critics as the “liberal opposition,” sparing no scorn for the critics themselves, liberalism as a philosophy, or its particular values.

Some opposition figures wear the label of liberal with pride, while others refuse to be labeled as such. At the same time, each side interprets liberalism and liberals in entirely different ways.

Understanding what propaganda means by “liberals” and “liberalism” is relatively straightforward. These terms serve as synonyms for Western influence — a collection of slogans about freedom and democracy under whose guise the insidious West seeks to undermine the nation.

In practical terms, Putin and his adherents are irritated by pointed criticism and seek to neutralize it by saying that “Western liberalism” is not an appropriate standard for evaluating Russia’s governance.

Understanding what propaganda means by “liberals” and “liberalism” is relatively straightforward. These terms serve as synonyms for Western influence — a collection of slogans about freedom and democracy under whose guise the insidious West seeks to undermine the nation.

In practical terms, Putin and his adherents are irritated by pointed criticism and seek to neutralize it by saying that “Western liberalism” is not an appropriate standard for evaluating Russia’s governance.

Their invectives against liberals and liberalism are not directed at actual adherents of liberal ideology, rendering rhetorical questions about individual freedom, the protection of rights, and private property pointless.

Propaganda, therefore, constructs a distorted worldview in which all opposition members are deemed liberals, and all liberals are seen as oppositionists. The long‑standing promotion of this narrative has sown much confusion, potentially exactly what the Kremlin has hoped for.

On one hand, it fosters constant mutual accusations within the opposition regarding deviations from liberal principles. On the other, it solidifies the belief that all opposition figures are liberals, thereby enabling speculation about the potential for a unified liberal opposition party‑despite the persistent disappointment that such unification never materializes.

The reality is that not all of Putin’s critics are liberals, just as not all consistent and principled liberals oppose Putin.

Their invectives against liberals and liberalism are not directed at actual adherents of liberal ideology, rendering rhetorical questions about individual freedom, the protection of rights, and private property pointless.

Propaganda, therefore, constructs a distorted worldview in which all opposition members are deemed liberals, and all liberals are seen as oppositionists. The long‑standing promotion of this narrative has sown much confusion, potentially exactly what the Kremlin has hoped for.

On one hand, it fosters constant mutual accusations within the opposition regarding deviations from liberal principles. On the other, it solidifies the belief that all opposition figures are liberals, thereby enabling speculation about the potential for a unified liberal opposition party‑despite the persistent disappointment that such unification never materializes.

The reality is that not all of Putin’s critics are liberals, just as not all consistent and principled liberals oppose Putin.

Within Russia’s opposition community, there are individuals with liberal views and those who merely self‑identify as liberals.

A closer examination reveals that these groups often operate with vastly different interpretations of terms and ideas. Below is a broad categorization of these groups, omitting names and political projects to avoid further controversy.

The “Old Liberals” are a small but resourceful group who maintains high‑level connections and influence. Closely associated with the Russian government, politics, and business of the 1990s and early 2000s, their view of liberalism is epitomized by Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, and, at times, by Augusto Pinochet.

They tend to idealize Boris Yeltsin and his administration, reacting strongly to any criticism of that period. Their views are inextricably linked to the economic reforms of the early 1990s, as their ideological battles have centered on justifying and defending those policies.

Alongside their economic doctrines, many have retained the attitudes of that era, including skepticism toward minority rights, moral conservatism, elitism, distrust of mass voters, and indifference‑if not outright hostility‑toward discussions of social guarantees and responsibilities.

Consequently, their version of liberalism often appears closer to conservatism, neoliberalism, or libertarianism by contemporary standards.

Within Russia’s opposition community, there are individuals with liberal views and those who merely self‑identify as liberals.

A closer examination reveals that these groups often operate with vastly different interpretations of terms and ideas. Below is a broad categorization of these groups, omitting names and political projects to avoid further controversy.

The “Old Liberals” are a small but resourceful group who maintains high‑level connections and influence. Closely associated with the Russian government, politics, and business of the 1990s and early 2000s, their view of liberalism is epitomized by Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, and, at times, by Augusto Pinochet.

They tend to idealize Boris Yeltsin and his administration, reacting strongly to any criticism of that period. Their views are inextricably linked to the economic reforms of the early 1990s, as their ideological battles have centered on justifying and defending those policies.

Alongside their economic doctrines, many have retained the attitudes of that era, including skepticism toward minority rights, moral conservatism, elitism, distrust of mass voters, and indifference‑if not outright hostility‑toward discussions of social guarantees and responsibilities.

Consequently, their version of liberalism often appears closer to conservatism, neoliberalism, or libertarianism by contemporary standards.

The “New Liberals” group consists of politicians, journalists, and activists who studied or began their careers in the 1990s and came of age in the 2000s, when it was already commonplace for the ruling elite to criticize the so‑called “party of power” liberals.

For them, liberalism aligns with American and European theories and practices from the late 1990s through the 2008 financial crisis‑a period that, according to Francis Fukuyama, marked the beginning of modern liberalism’s crisis. This group advocates for a more inclusive democracy, tolerance, and multiculturalism.

Their main challenge is their reluctance to confront the questions raised by the 2008 crisis and its aftermath. Can liberalism, as both an economic and political theory, still function in the wake of these crises and ensuing disillusionment?

In Western democracies, classical liberal parties have struggled to answer this question, often being forced to shift either left or right‑or risk losing their electorate entirely. The struggles of Germany’s Free Democratic Party (FDP), long seen by many Russian liberals as a model, illustrate this challenge. As the 2025 elections approach, the party faces an uncertain future in the Bundestag.

The “New Liberals” group consists of politicians, journalists, and activists who studied or began their careers in the 1990s and came of age in the 2000s, when it was already commonplace for the ruling elite to criticize the so‑called “party of power” liberals.

For them, liberalism aligns with American and European theories and practices from the late 1990s through the 2008 financial crisis‑a period that, according to Francis Fukuyama, marked the beginning of modern liberalism’s crisis. This group advocates for a more inclusive democracy, tolerance, and multiculturalism.

Their main challenge is their reluctance to confront the questions raised by the 2008 crisis and its aftermath. Can liberalism, as both an economic and political theory, still function in the wake of these crises and ensuing disillusionment?

In Western democracies, classical liberal parties have struggled to answer this question, often being forced to shift either left or right‑or risk losing their electorate entirely. The struggles of Germany’s Free Democratic Party (FDP), long seen by many Russian liberals as a model, illustrate this challenge. As the 2025 elections approach, the party faces an uncertain future in the Bundestag.

Young Liberals. Potentially the largest, yet, least organized group within Russian liberal civil society are the “young liberals” — those born in the 2000s, who came of age under Putin’s rule.

For them, a liberal is, above all, an opponent of Putin and an advocate of a pro‑Western (more often pro‑European than pro‑American) political orientation, broad democracy, inclusiveness, and an open economy.

However, given the stigma surrounding liberalism in Russian political discourse, many of them shun the label and may even reject it outright, despite sincerely embracing liberal values and principles.

The core issue remains that those who most openly self‑identify as liberals‑often representatives of the older generation‑tend to alienate younger activists from associating with liberalism in any form. Addressing this requires an honest, open political dialogue about the future of Russian liberalism, its goals, and its objectives‑especially within Russia.

Young Liberals. Potentially the largest, yet, least organized group within Russian liberal civil society are the “young liberals” — those born in the 2000s, who came of age under Putin’s rule.

For them, a liberal is, above all, an opponent of Putin and an advocate of a pro‑Western (more often pro‑European than pro‑American) political orientation, broad democracy, inclusiveness, and an open economy.

However, given the stigma surrounding liberalism in Russian political discourse, many of them shun the label and may even reject it outright, despite sincerely embracing liberal values and principles.

The core issue remains that those who most openly self‑identify as liberals‑often representatives of the older generation‑tend to alienate younger activists from associating with liberalism in any form. Addressing this requires an honest, open political dialogue about the future of Russian liberalism, its goals, and its objectives‑especially within Russia.

Liberals should learn to talk to people in Russia, both supporters and skeptics, by offering compelling programs and strong leaders who can defend and promote them. This is a realistic goal for that segment of Russian society that embraces liberal views and envisions liberalism as part of the country’s future.

Russian liberalism has a long history, political traditions, and the potential to become one of the influential forces in the future democratic and federative Russia.

Liberals should learn to talk to people in Russia, both supporters and skeptics, by offering compelling programs and strong leaders who can defend and promote them. This is a realistic goal for that segment of Russian society that embraces liberal views and envisions liberalism as part of the country’s future.

Russian liberalism has a long history, political traditions, and the potential to become one of the influential forces in the future democratic and federative Russia.

Even if Russian liberals were to form a unified party to run in elections, they would not become the dominant political force. The German FDP, referenced earlier, achieved its best electoral performance in 2008 with 14.6% of the vote.

Historically, its highest support levels stood at 12.8% in 1961, 11.9% in 1949, and 11% in 1990. Outside of those spikes, Germany’s liberal party hovered around 10% voter support and, in the 2013 elections, failed to secure any Bundestag seats.

Even if Russian liberals were to form a unified party to run in elections, they would not become the dominant political force. The German FDP, referenced earlier, achieved its best electoral performance in 2008 with 14.6% of the vote.

Historically, its highest support levels stood at 12.8% in 1961, 11.9% in 1949, and 11% in 1990. Outside of those spikes, Germany’s liberal party hovered around 10% voter support and, in the 2013 elections, failed to secure any Bundestag seats.

This is discouraging news. However, the good news is that a consensus has emerged around the idea of Russia transitioning to a parliamentary democracy, where a party can gain government influence not only through electoral victory but also by joining a coalition (read more in the “Transition” and other projects).

This is discouraging news. However, the good news is that a consensus has emerged around the idea of Russia transitioning to a parliamentary democracy, where a party can gain government influence not only through electoral victory but also by joining a coalition (read more in the “Transition” and other projects).

To improve their electoral prospects, Russian liberals might consider rebranding, adopting a new or more neutral name adapted to Russian realities‑perhaps calling themselves Republicans, Free Democrats, or something similar.

Liberalism is unlikely to become the singular, unifying ideology — first of the Russian emigrant community and opposition to Putin, and later of a new Russia (for further discussion, see Krasheninnikov, Lobanov).

To improve their electoral prospects, Russian liberals might consider rebranding, adopting a new or more neutral name adapted to Russian realities‑perhaps calling themselves Republicans, Free Democrats, or something similar.

Liberalism is unlikely to become the singular, unifying ideology — first of the Russian emigrant community and opposition to Putin, and later of a new Russia (for further discussion, see Krasheninnikov, Lobanov).

Instead, a more pragmatic and attainable goal is the formation of a liberal party. Though this may take time, the emergence of several liberal political groups capable of articulating their ideas and programs in an engaging and accessible manner would be beneficial for society.

As long as work in Russia remains challenging, the necessary conditions exist to develop programs, concepts, leaders, and organizational structures that could, within months, emerge as a political force for a new Russia once even minimal opportunities arise.

Instead, a more pragmatic and attainable goal is the formation of a liberal party. Though this may take time, the emergence of several liberal political groups capable of articulating their ideas and programs in an engaging and accessible manner would be beneficial for society.

As long as work in Russia remains challenging, the necessary conditions exist to develop programs, concepts, leaders, and organizational structures that could, within months, emerge as a political force for a new Russia once even minimal opportunities arise.

Challenges and Opportunities

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

December 15, 2024

Article

Article What challenges will it face in the coming years?

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

January 09, 2025

Article

Article A few examples from recent Russian history

By Alexander Zaritsky

January 21, 2025

Challenges and Opportunities

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

December 15, 2024

Article

Article What challenges will it face in the coming years?

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

January 09, 2025

Article

Article A few examples from recent Russian history

By Alexander Zaritsky

January 21, 2025