The European Elections and their Impact

By Roland Freudenstein June 12, 2024

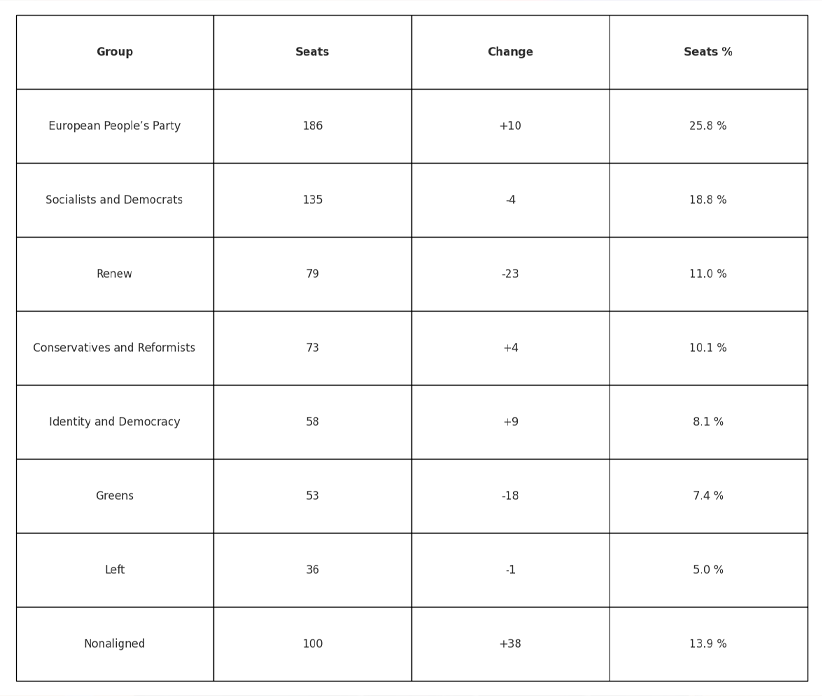

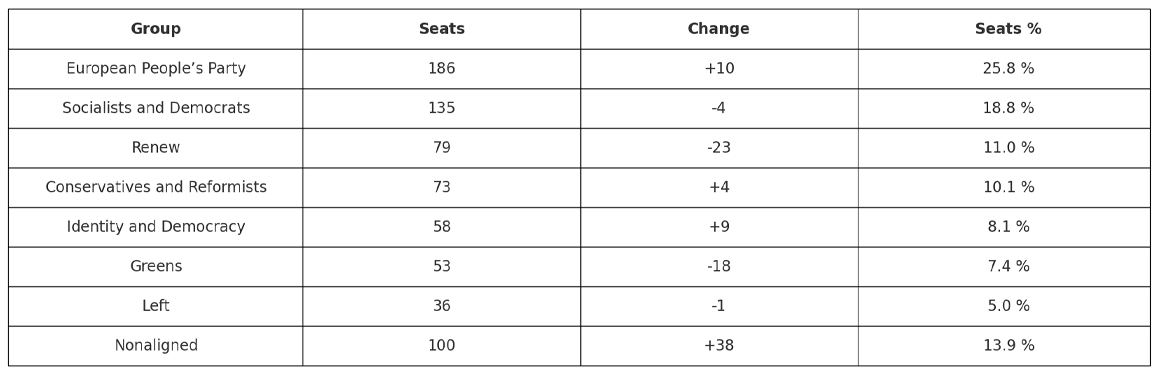

Some figures are preliminary because many of the Nonaligned will eventually choose a group, or try to create a new one — most likely on the Right.

Some figures are preliminary because many of the Nonaligned will eventually choose a group, or try to create a new one — most likely on the Right.

The now conventional wisdom is that ‘the center held’ in this election because the Right (ECR & ID) only gained about 20–40 seats (some are still ‘hidden’ in Nonaligned). That is correct, but the substantial losses on the Left & Centre (Greens and Liberals) do signal a rightward shift — and the Centre Right’s (European People’s Party, EPP) growth has to be seen in this context, too.

The project of a unified pan‑European Right in the Parliament, much talked about by the national populists before the elections, is hardly on the cards. The disagreements on Ukraine, Russia and China are too big, also on deficit spending and the politics of history (for example, Polish and German, German and French, or Hungarian and Romanian nationalists can hardly agree on a common view of the past).

Moreover, both the National Rally (RN) in France and the Brothers of Italy try to appear more eligible to the mainstream but are (at least at the moment) incompatible with each other. All this means that there will most likely remain two, if not three, different groups on the Right in the next EP.

The now conventional wisdom is that ‘the center held’ in this election because the Right (ECR & ID) only gained about 20–40 seats (some are still ‘hidden’ in Nonaligned). That is correct, but the substantial losses on the Left & Centre (Greens and Liberals) do signal a rightward shift — and the Centre Right’s (European People’s Party, EPP) growth has to be seen in this context, too.

The project of a unified pan‑European Right in the Parliament, much talked about by the national populists before the elections, is hardly on the cards. The disagreements on Ukraine, Russia and China are too big, also on deficit spending and the politics of history (for example, Polish and German, German and French, or Hungarian and Romanian nationalists can hardly agree on a common view of the past).

Moreover, both the National Rally (RN) in France and the Brothers of Italy try to appear more eligible to the mainstream but are (at least at the moment) incompatible with each other. All this means that there will most likely remain two, if not three, different groups on the Right in the next EP.

Altogether, in terms of political topics, the European Parliament has shifted towards a more restrictive migration policy, less emphasis on green and gender issues and less enthusiasm for shifting elements of national sovereignty to the EU institutions.

On all these issues, the EPP has a strong conservative wing that will feel tempted to vote with parties further Right. On helping Ukraine and confronting the Kremlin, however, the EPP and even parts of ECR are at the forefront of a hawkish line. The solid pro‑Ukraine and anti‑Kremlin majority of the European Parliament has not significantly moved.

Moreover, the EP plays a decisive role on these issues only where they touch upon budgetary, industrial and legal aspects — foreign and security policy are the remit of the EU Council.

Altogether, in terms of political topics, the European Parliament has shifted towards a more restrictive migration policy, less emphasis on green and gender issues and less enthusiasm for shifting elements of national sovereignty to the EU institutions.

On all these issues, the EPP has a strong conservative wing that will feel tempted to vote with parties further Right. On helping Ukraine and confronting the Kremlin, however, the EPP and even parts of ECR are at the forefront of a hawkish line. The solid pro‑Ukraine and anti‑Kremlin majority of the European Parliament has not significantly moved.

Moreover, the EP plays a decisive role on these issues only where they touch upon budgetary, industrial and legal aspects — foreign and security policy are the remit of the EU Council.

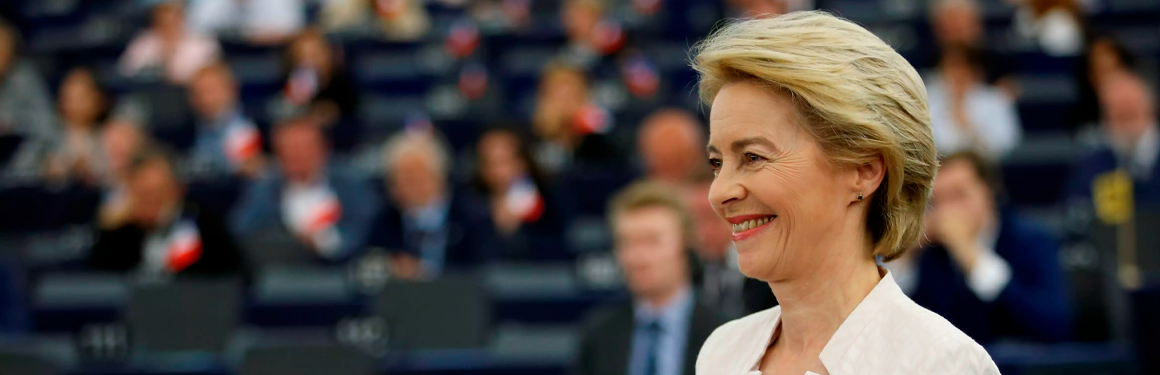

Ursula von der Leyen is strengthened in her ambition for Commission President, largely because of the EPP result. The Council will very probably nominate her (no national veto possible; qualified majority decides) on 28/29 June in the extraordinary informal summit.

Ursula von der Leyen is strengthened in her ambition for Commission President, largely because of the EPP result. The Council will very probably nominate her (no national veto possible; qualified majority decides) on 28/29 June in the extraordinary informal summit.

However, she might face a struggle to get a majority in Parliament in mid‑July. The 3 centrist groups EPP, Renew and S&D together have a clear mathematical majority (400 out of 720) but group discipline in the EP is much lower than in national Parliaments, and some MEPs from all 3 groups have already announced to vote against her. She may therefore need the support of the Greens — and possibly even of parts of ECR, which may again cost her on the Left.

But the likely outcome is still a second term for Ursula von der Leyen, which is again good news for Ukraine and Russia’s democrats because of her clear and early stance on defending freedom where it is threatened by Putin.

The other top jobs are Council President, High Representative and President of Parliament — and these will be divvied up among the centrist political families (EPP, S&D, Renew); unlikely to be affected by the result of the election.

However, she might face a struggle to get a majority in Parliament in mid‑July. The 3 centrist groups EPP, Renew and S&D together have a clear mathematical majority (400 out of 720) but group discipline in the EP is much lower than in national Parliaments, and some MEPs from all 3 groups have already announced to vote against her. She may therefore need the support of the Greens — and possibly even of parts of ECR, which may again cost her on the Left.

But the likely outcome is still a second term for Ursula von der Leyen, which is again good news for Ukraine and Russia’s democrats because of her clear and early stance on defending freedom where it is threatened by Putin.

The other top jobs are Council President, High Representative and President of Parliament — and these will be divvied up among the centrist political families (EPP, S&D, Renew); unlikely to be affected by the result of the election.

The biggest danger in the current right wing shift of European politics is in the member states and, as a consequence, in the European Council.

In France, Germany and Austria, the extreme Right has become significantly stronger but the consequences are different in each case. Austria may see a nationalist‑led (and more pro‑Kremlin) government after elections later this year.

Germany is becoming less stable but will not have nationalists in power in Berlin anytime soon; France is in turmoil, however, with very uncertain prospects (see next point).

On the other hand, national populists have had disappointing results in all three Nordic countries where the Left has been strengthened and in Poland, Hungary and Slovakia where the centre either won or made sensational gains.

Hungary is particularly remarkable because of the surprising and sudden success of a former Fidesz insider turned enemy of Viktor Orban who only appeared 4 months ago and scored 30% compared to Fidesz’ relatively meager 45%, leaving Fidesz in shock.

The biggest danger in the current right wing shift of European politics is in the member states and, as a consequence, in the European Council.

In France, Germany and Austria, the extreme Right has become significantly stronger but the consequences are different in each case. Austria may see a nationalist‑led (and more pro‑Kremlin) government after elections later this year.

Germany is becoming less stable but will not have nationalists in power in Berlin anytime soon; France is in turmoil, however, with very uncertain prospects (see next point).

On the other hand, national populists have had disappointing results in all three Nordic countries where the Left has been strengthened and in Poland, Hungary and Slovakia where the centre either won or made sensational gains.

Hungary is particularly remarkable because of the surprising and sudden success of a former Fidesz insider turned enemy of Viktor Orban who only appeared 4 months ago and scored 30% compared to Fidesz’ relatively meager 45%, leaving Fidesz in shock.

While Olaf Scholz and Emmanuel Macron are weakened by the poor performance of their parties and therefore less powerful on the EU stage, 2 leaders have been strengthened: Italy’s Giorgia Meloni and Poland’s Donald Tusk. They will play bigger roles in future, which is good news for Ukraine and Russian democrats.

While Olaf Scholz and Emmanuel Macron are weakened by the poor performance of their parties and therefore less powerful on the EU stage, 2 leaders have been strengthened: Italy’s Giorgia Meloni and Poland’s Donald Tusk. They will play bigger roles in future, which is good news for Ukraine and Russian democrats.

Developments in France may become the most immediate and also upsetting consequence of the European election. President Macron’s poor showing (less than half the votes of National Rally) and subsequent decision to dissolve France’s Parliament and have snap elections within 4 weeks, has thrown France into turmoil and cast a shadow of uncertainty over France’s ability to continue to play its role as a leader.

In the best case scenario, Macron profits from his courageous decision and from the fact that national elections have traditionally much higher turnouts (and therefore more centrist votes) than European ones. But first tentative polls indicate otherwise and suggest a parliamentary majority for the National Rally.

That would most likely force Macron to nominate an RN Prime Minister (Jordan Bardella) — a so‑called cohabitation for another 2 ½ years in which Macron could continue to take the big decisions in foreign and defence policy, but for all decisions involving budget, sending weapons and troops etc., would sooner or later need the agreement of Parliament.

Developments in France may become the most immediate and also upsetting consequence of the European election. President Macron’s poor showing (less than half the votes of National Rally) and subsequent decision to dissolve France’s Parliament and have snap elections within 4 weeks, has thrown France into turmoil and cast a shadow of uncertainty over France’s ability to continue to play its role as a leader.

In the best case scenario, Macron profits from his courageous decision and from the fact that national elections have traditionally much higher turnouts (and therefore more centrist votes) than European ones. But first tentative polls indicate otherwise and suggest a parliamentary majority for the National Rally.

That would most likely force Macron to nominate an RN Prime Minister (Jordan Bardella) — a so‑called cohabitation for another 2 ½ years in which Macron could continue to take the big decisions in foreign and defence policy, but for all decisions involving budget, sending weapons and troops etc., would sooner or later need the agreement of Parliament.

That might seriously hamper France’s recent trajectory of staunchly supporting Ukraine and boldly opposing Putin. France would generally be weakened as a leader in the EU at a time when Germany under Scholz is showing precisely the same lack of determination and courage. But it is too early to call Macron a lame duck; the upcoming weeks will be decisive.

That might seriously hamper France’s recent trajectory of staunchly supporting Ukraine and boldly opposing Putin. France would generally be weakened as a leader in the EU at a time when Germany under Scholz is showing precisely the same lack of determination and courage. But it is too early to call Macron a lame duck; the upcoming weeks will be decisive.

The absence of a rightward landslide should not lead Russian democrats to complacency, nor should the prospect of more powerful pro‑Putin parties in countries like France, Germany and Austria cause them to despair. Italy and Poland will be more influential and require more attention.

Russian democrats and their allies in the EU should take this election as an encouragement to engage with all political forces and parties in Europe that are not openly pro‑Kremlin.

They should redouble the messaging on their key issues: confronting the Kremlin, helping Ukraine, preparing for radical change in Moscow and making use of the input and contributions of Free Russians in this effort.

The absence of a rightward landslide should not lead Russian democrats to complacency, nor should the prospect of more powerful pro‑Putin parties in countries like France, Germany and Austria cause them to despair. Italy and Poland will be more influential and require more attention.

Russian democrats and their allies in the EU should take this election as an encouragement to engage with all political forces and parties in Europe that are not openly pro‑Kremlin.

They should redouble the messaging on their key issues: confronting the Kremlin, helping Ukraine, preparing for radical change in Moscow and making use of the input and contributions of Free Russians in this effort.

How Russians in exile can help counter Putin’s narratives

By Roland Freudenstein

October 11, 2024

Policy Brief

Policy Brief The Impact of Entry Restrictions, Barriers to Protection and Possible Solutions

By Gleb Bogush

August 29, 2024

How Russians in exile can help counter Putin’s narratives

By Roland Freudenstein

October 11, 2024

Policy Brief

Policy Brief The Impact of Entry Restrictions, Barriers to Protection and Possible Solutions

By Gleb Bogush

August 29, 2024