Recent Sanctions of OFAC Targeting Russia’s Oil and Gas Industry

Objectively speaking, the evolving US sanctions regime has had a significant impact on the Russian oil and gas industry

By Mikhail Krutikhin February 29, 2024

Objectively speaking, the evolving US sanctions regime has had a significant impact on the Russian oil and gas industry

By Mikhail Krutikhin February 29, 2024

Objectively speaking, the evolving US sanctions regime has had a significant impact on the Russian oil and gas industry.

Russia’s energy sector has been targeted by several types of sanctions. They have restricted access to advanced technologies and equipment; restricted access to capital borrowing; and introduced bans on participation in Russian upstream oil projects on the continental shelf.

The most conspicuous examples of the impact of those sanctions include the cancelation of a joint project between ExxonMobil and Rosneft, worth over $4.5 billion, to explore offshore reserves in the Kara Sea and Black Sea; and the development of the South Kirinskoye oil and gas project off Sakhalin Island which was stymied due to lack of access to subsea technologies, which cannot be provided because the field contains huge reserves of oil in addition to natural gas, and offshore oil is subject to sanctions.

The Kara Sea venture was stopped due to the 2014 sanctions. A single wildcat well was drilled but had to be plugged and abandoned without testing.

Objectively speaking, the evolving US sanctions regime has had a significant impact on the Russian oil and gas industry.

Russia’s energy sector has been targeted by several types of sanctions. They have restricted access to advanced technologies and equipment; restricted access to capital borrowing; and introduced bans on participation in Russian upstream oil projects on the continental shelf.

The most conspicuous examples of the impact of those sanctions include the cancelation of a joint project between ExxonMobil and Rosneft, worth over $4.5 billion, to explore offshore reserves in the Kara Sea and Black Sea; and the development of the South Kirinskoye oil and gas project off Sakhalin Island which was stymied due to lack of access to subsea technologies, which cannot be provided because the field contains huge reserves of oil in addition to natural gas, and offshore oil is subject to sanctions.

The Kara Sea venture was stopped due to the 2014 sanctions. A single wildcat well was drilled but had to be plugged and abandoned without testing.

The February 2024 sanctions, however, according to author’s insider sources in Russian oil and gas companies, are not going to make a big difference. They appear to be a moderate amendment rather than a dramatic enhancement of the international sanctions’ regime.

The February 2024 sanctions, however, according to author’s insider sources in Russian oil and gas companies, are not going to make a big difference. They appear to be a moderate amendment rather than a dramatic enhancement of the international sanctions’ regime.

Beginning with December 2022 and throughout 2023, the price cap on Russian crude oil and refined products delivered by sea had clear effects, despite the frantic circumvention efforts by Russian operators.

As a direct result of the cap, total oil and gas revenues in Russia’s federal budget fell from $166 billion in 2022 to $103 billion in 2023.

The Kremlin has failed to offset this loss despite having forced Gazprom and major oil companies to pay an ‘extra’ levy over the regular mineral extraction tax (the Russian name for royalty).

The basic idea of the price cap is to keep Russian oil flowing to the global market in order to prevent a shortage of supply, and simultaneously decrease the influx of oil revenues to the Russian budget, thusly reducing resources to fund the aggression in Ukraine. Therefore, there is a natural limit to the effectiveness of such sanctions against Russia’s oil industry.

Beginning with December 2022 and throughout 2023, the price cap on Russian crude oil and refined products delivered by sea had clear effects, despite the frantic circumvention efforts by Russian operators.

As a direct result of the cap, total oil and gas revenues in Russia’s federal budget fell from $166 billion in 2022 to $103 billion in 2023.

The Kremlin has failed to offset this loss despite having forced Gazprom and major oil companies to pay an ‘extra’ levy over the regular mineral extraction tax (the Russian name for royalty).

The basic idea of the price cap is to keep Russian oil flowing to the global market in order to prevent a shortage of supply, and simultaneously decrease the influx of oil revenues to the Russian budget, thusly reducing resources to fund the aggression in Ukraine. Therefore, there is a natural limit to the effectiveness of such sanctions against Russia’s oil industry.

Faced with the price cap, the Russians adopted a multi‑faceted strategy. To begin with, the exporters enhanced their habitual method of tax evasion by selling oil through intermediaries‑often the companies’ wholly‑owned subsidiaries registered abroad.

Lukoil was selling crude to its trading arm Litasco, for example. The taxes on exported oil were charged on the first selling price, and the exporters collected a premium from reselling it with a premium through a chain of proxies.

When a consignment of crude reached, say, India, an Indian refinery paid about $70 per barrel even though the first buyer had paid just $57.

The enforcers of the sanctions were powerless to fight such schemes. They could check the loading documents and the documents held by the tanker’s captain, only to find that the papers showed that the price was under the cap, and the insurance documents were also in perfect order.

Faced with the price cap, the Russians adopted a multi‑faceted strategy. To begin with, the exporters enhanced their habitual method of tax evasion by selling oil through intermediaries‑often the companies’ wholly‑owned subsidiaries registered abroad.

Lukoil was selling crude to its trading arm Litasco, for example. The taxes on exported oil were charged on the first selling price, and the exporters collected a premium from reselling it with a premium through a chain of proxies.

When a consignment of crude reached, say, India, an Indian refinery paid about $70 per barrel even though the first buyer had paid just $57.

The enforcers of the sanctions were powerless to fight such schemes. They could check the loading documents and the documents held by the tanker’s captain, only to find that the papers showed that the price was under the cap, and the insurance documents were also in perfect order.

Moreover, enforcing the sanctions on intermediaries made no sense as the idea of the price cap was to trim down the taxes the exporters paid to the Russian federal budget rather than the additional profit reaped by the intermediaries.

Punishing intermediary traders and targeting such proxies as “shadow tankers” and their owners have no impact on the size of the revenues to the budget. The bulk of that unsanctioned profit does not return to Russia but remains in the intermediaries’ bank accounts someplace in Hong Kong, Singapore, or the UAE.

Russian analysts associated either with the government or with major companies occasionally claim in their media interviews that the hoarded sums are either repatriated or used to finance smuggled war materials.

The author’s contacts in foreign offices of Russian exporters insist that only a very small portion of the hoards is used in the interests of the government. The hoarded money is usually appropriated by Russian companies and high‑level corrupt officials in the presidential administration and the government.

Moreover, enforcing the sanctions on intermediaries made no sense as the idea of the price cap was to trim down the taxes the exporters paid to the Russian federal budget rather than the additional profit reaped by the intermediaries.

Punishing intermediary traders and targeting such proxies as “shadow tankers” and their owners have no impact on the size of the revenues to the budget. The bulk of that unsanctioned profit does not return to Russia but remains in the intermediaries’ bank accounts someplace in Hong Kong, Singapore, or the UAE.

Russian analysts associated either with the government or with major companies occasionally claim in their media interviews that the hoarded sums are either repatriated or used to finance smuggled war materials.

The author’s contacts in foreign offices of Russian exporters insist that only a very small portion of the hoards is used in the interests of the government. The hoarded money is usually appropriated by Russian companies and high‑level corrupt officials in the presidential administration and the government.

It is true, however, that the Russian government has taken some steps to increase the size of the tax it collects from the exported crude oil and refined products.

Instead of taxing the first selling price, it has introduced a virtual price marker: the price of Dated Brent is used as a base and then a discount is counted in to make the officially accepted export price.

The size of this discount is adjusted monthly. In 2023, this trick helped the government to increase the oil revenues to the federal budget by about $10 billion.

The February 2024 series of OFAC sanctions target a relatively small number, fewer than 50, of specific tankers and shipowners that had been caught red‑handed with a cargo of Russian oil they were transporting without the documented proof of complying with the price cap.

The scope of this measure, even though the media may depict it as a real fight against the smugglers of overpriced Russian oil, makes these “exemplary” punishments just a drop in the sea. The number of vessels and proxy companies engaged in the intermediary chains is too great to identify, catch, or punish. Estimates of this fleet vary between 400 and over a thousand.

It is true, however, that the Russian government has taken some steps to increase the size of the tax it collects from the exported crude oil and refined products.

Instead of taxing the first selling price, it has introduced a virtual price marker: the price of Dated Brent is used as a base and then a discount is counted in to make the officially accepted export price.

The size of this discount is adjusted monthly. In 2023, this trick helped the government to increase the oil revenues to the federal budget by about $10 billion.

The February 2024 series of OFAC sanctions target a relatively small number, fewer than 50, of specific tankers and shipowners that had been caught red‑handed with a cargo of Russian oil they were transporting without the documented proof of complying with the price cap.

The scope of this measure, even though the media may depict it as a real fight against the smugglers of overpriced Russian oil, makes these “exemplary” punishments just a drop in the sea. The number of vessels and proxy companies engaged in the intermediary chains is too great to identify, catch, or punish. Estimates of this fleet vary between 400 and over a thousand.

Likewise, the February 2024 sanctions against Sovcomflot, a government‑controlled shipping company, are unlikely to effect change.

Today, that company is little more than an empty shell: it has transferred most of its tanker fleet to obscure shipping companies in the UAE and elsewhere and had them certified and insured by somewhat dubious firms from India and other countries.

From time to time the new owners of Sovcomflot ships are identified by independent researchers and journalists, and included in the sanctioned lists, but the majority of the “shadow” vessels and their formal owners remain unnoticed and unpunished.

Therefore, the sanctions against intermediaries that defy the price cap cannot be recognized as efficient. They do not target the flow of revenues to Russia’s federal budget, and they cannot identify and punish the hundreds of entities involved in these schemes.

In the current form, the sanctions can only be an overhyped example of what may happen to the culprits, but they really do not threaten anyone, and are not a real deterrent.

Likewise, the February 2024 sanctions against Sovcomflot, a government‑controlled shipping company, are unlikely to effect change.

Today, that company is little more than an empty shell: it has transferred most of its tanker fleet to obscure shipping companies in the UAE and elsewhere and had them certified and insured by somewhat dubious firms from India and other countries.

From time to time the new owners of Sovcomflot ships are identified by independent researchers and journalists, and included in the sanctioned lists, but the majority of the “shadow” vessels and their formal owners remain unnoticed and unpunished.

Therefore, the sanctions against intermediaries that defy the price cap cannot be recognized as efficient. They do not target the flow of revenues to Russia’s federal budget, and they cannot identify and punish the hundreds of entities involved in these schemes.

In the current form, the sanctions can only be an overhyped example of what may happen to the culprits, but they really do not threaten anyone, and are not a real deterrent.

Just as toothless is the February 2024 inclusion of Russian geological and geophysical organizations in the SDN lists: the umbrella firm, Rosgeologia, and some of its subsidiaries.

Rosgeologia, established in July 2011 as a state holding for over 40 small and medium‑sized geological and geophysical entities, does not contribute significantly to Russia’s budget revenues. Most of the units do not make any profit, and Rosgeologia itself is in the red.

The parent company is, in fact, just an instrument of redistributing state subsidies and contracts to corrupt administrators. It is not clear at all how the sanctions against these entities can help erode Russia’s military potential.

In contrast, the sanctions that prevent Russian and international shipbuilders from supplying ice‑resistant and ordinary tankers and other ships to Russia are perfectly effective.

They are certain to decrease the number of such vessels at the disposal of Russian operators and undermine the prospects of several major projects.

There is, however, a snag. The projects that need those vessels are not expected to yield any revenues to the Russian budget for many years.

Just as toothless is the February 2024 inclusion of Russian geological and geophysical organizations in the SDN lists: the umbrella firm, Rosgeologia, and some of its subsidiaries.

Rosgeologia, established in July 2011 as a state holding for over 40 small and medium‑sized geological and geophysical entities, does not contribute significantly to Russia’s budget revenues. Most of the units do not make any profit, and Rosgeologia itself is in the red.

The parent company is, in fact, just an instrument of redistributing state subsidies and contracts to corrupt administrators. It is not clear at all how the sanctions against these entities can help erode Russia’s military potential.

In contrast, the sanctions that prevent Russian and international shipbuilders from supplying ice‑resistant and ordinary tankers and other ships to Russia are perfectly effective.

They are certain to decrease the number of such vessels at the disposal of Russian operators and undermine the prospects of several major projects.

There is, however, a snag. The projects that need those vessels are not expected to yield any revenues to the Russian budget for many years.

One such project is Vostok Oil of Rosneft. The state‑run company’s CEO Igor Sechin promised President Vladimir Putin to export 30 million tons of crude oil annually via Arctic waters starting with 2024, but this goal requires offloading at least one average Arctic class tanker daily.

In reality, Rosneft does not possess the required tankers and cannot hire them on the global shipping market (there is simply not enough of such vessels anywhere).

Vostok Oil does not need those tankers because Sechin’s public promises of huge production and export flows were not intended to be realized. The whole project is just a tool of misappropriation of hugely exaggerated state‑sponsored budgets.

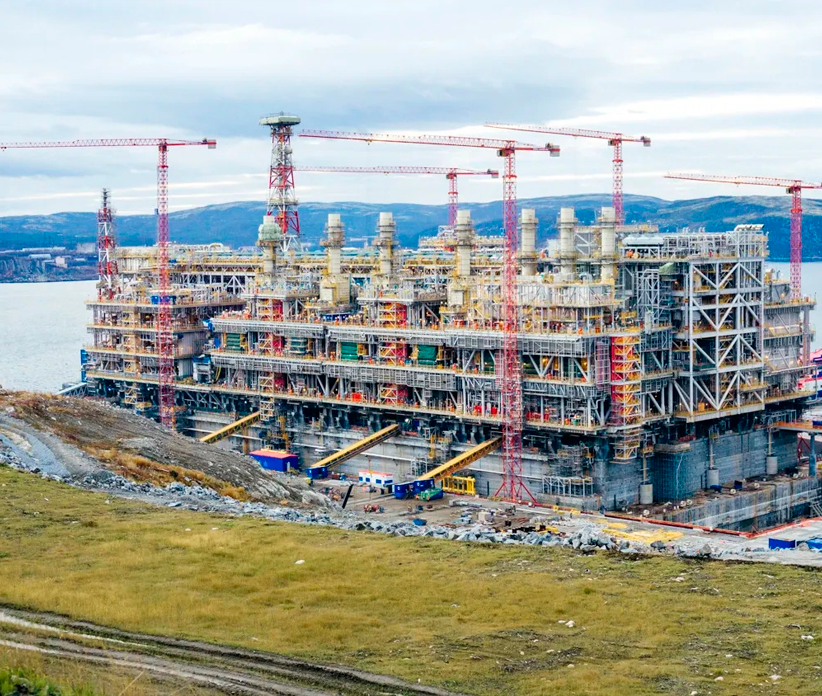

Another potential user of Arctic‑class vessels is Novatek, which needs ice‑resistant LNG carriers for its ongoing big project, Arctic LNG 2. Without these vessels, the project cannot meet its targets. The first of its three LNG trains was commissioned in December 2023, but cannot start exporting LNG because the company cannot procure the carriers.

One such project is Vostok Oil of Rosneft. The state‑run company’s CEO Igor Sechin promised President Vladimir Putin to export 30 million tons of crude oil annually via Arctic waters starting with 2024, but this goal requires offloading at least one average Arctic class tanker daily.

In reality, Rosneft does not possess the required tankers and cannot hire them on the global shipping market (there is simply not enough of such vessels anywhere).

Vostok Oil does not need those tankers because Sechin’s public promises of huge production and export flows were not intended to be realized. The whole project is just a tool of misappropriation of hugely exaggerated state‑sponsored budgets.

Another potential user of Arctic‑class vessels is Novatek, which needs ice‑resistant LNG carriers for its ongoing big project, Arctic LNG 2. Without these vessels, the project cannot meet its targets. The first of its three LNG trains was commissioned in December 2023, but cannot start exporting LNG because the company cannot procure the carriers.

Neither project contributes anything to Russia’s federal budget. Rosneft’s fake Vostok Oil is a parasite on the government’s funds with bleak prospects of becoming commercially viable; and Arctic LNG 2 operates under a special fiscal regime being excused from all taxes for the first twelve years from the start of operations in December 2023.

Neither project contributes anything to Russia’s federal budget. Rosneft’s fake Vostok Oil is a parasite on the government’s funds with bleak prospects of becoming commercially viable; and Arctic LNG 2 operates under a special fiscal regime being excused from all taxes for the first twelve years from the start of operations in December 2023.

Attacking such projects with sanctions does not in any way impact the Kremlin’s financial resources to continue its war in Ukraine.

Attacking such projects with sanctions does not in any way impact the Kremlin’s financial resources to continue its war in Ukraine.

Russia’s LNG industry is clearly a prominent target of the recent OFAC sanctions.

Novatek, which has completed two of the planned three gas liquefaction trains for Arctic LNG 2, faces problems with assembling the third train with assistance of Chinese manufacturers because of the departure of international companies that were supposed to supply sophisticated technologies and equipment.

The foreign partners of Novatek in this project‑France’s TotalEnergies, China’s CNPC and CNOOC, and Japan’s consortium of Mitsui and JOGMEC- have been forced to stop financing the work and canceled their long‑term offtaker contracts.

The sanctions target the planned operations of two LNG reloading hubs of Novatek near Murmansk in the Barents Sea and on the Kamchatka Peninsula. The sanctions will increase transportation costs and seriously complicate the logistics for Arctic LNG 2 and for Novatek’s previous project, Yamal LNG.

Russia’s LNG industry is clearly a prominent target of the recent OFAC sanctions.

Novatek, which has completed two of the planned three gas liquefaction trains for Arctic LNG 2, faces problems with assembling the third train with assistance of Chinese manufacturers because of the departure of international companies that were supposed to supply sophisticated technologies and equipment.

The foreign partners of Novatek in this project‑France’s TotalEnergies, China’s CNPC and CNOOC, and Japan’s consortium of Mitsui and JOGMEC- have been forced to stop financing the work and canceled their long‑term offtaker contracts.

The sanctions target the planned operations of two LNG reloading hubs of Novatek near Murmansk in the Barents Sea and on the Kamchatka Peninsula. The sanctions will increase transportation costs and seriously complicate the logistics for Arctic LNG 2 and for Novatek’s previous project, Yamal LNG.

Another target is Gazprom’s large‑scale LNG project at Ust‑Luga on the Baltic coast, even though its prospects have been hazy enough without any sanctioning‑the project had not been able to access to LNG technologies.

Therefore, OFAC’s new sanctions against Russian LNG projects fall short of their purpose. The Russian budget does not receive anything from them in the form of taxes (apart from the taxes on Novatek’s profit as a commercial company but not as a partner in the specific LNG projects).

Perhaps they were driven by domestic political motivations‑as a nod by the Biden Administration to the US LNG business. Under the pretext of fighting against Russia’s militarized budget, it is in fact creating problems for exports of LNG from Russia to the same markets where American companies are boosting their share of business.

This may help ameliorate the fallout from the delay of new LNG projects in the US, benefitting competitors such as Qatar and Australia.

Another target is Gazprom’s large‑scale LNG project at Ust‑Luga on the Baltic coast, even though its prospects have been hazy enough without any sanctioning‑the project had not been able to access to LNG technologies.

Therefore, OFAC’s new sanctions against Russian LNG projects fall short of their purpose. The Russian budget does not receive anything from them in the form of taxes (apart from the taxes on Novatek’s profit as a commercial company but not as a partner in the specific LNG projects).

Perhaps they were driven by domestic political motivations‑as a nod by the Biden Administration to the US LNG business. Under the pretext of fighting against Russia’s militarized budget, it is in fact creating problems for exports of LNG from Russia to the same markets where American companies are boosting their share of business.

This may help ameliorate the fallout from the delay of new LNG projects in the US, benefitting competitors such as Qatar and Australia.

Imposing sanctions on the Russian gas is of very limited utility. Putin himself has killed Gazprom’s westward exports without securing an adequate alternative in the east. Putin’s threats to “freeze” Europe have been, in fact, followed by his dramatic cuts of natural gas supply to the EU.

Russian oil trade, however, offers powerful levers to the sanction’s authorities:

Imposing sanctions on the Russian gas is of very limited utility. Putin himself has killed Gazprom’s westward exports without securing an adequate alternative in the east. Putin’s threats to “freeze” Europe have been, in fact, followed by his dramatic cuts of natural gas supply to the EU.

Russian oil trade, however, offers powerful levers to the sanction’s authorities:

To make such “secondary” sanctions fully efficient, a comprehensive approach is needed, which is hardly possible because of resistance from such players as China.

The risks are obvious. Nobody wants a full‑scale war in the world’s banking system. Nevertheless, the US has plenty of room to cautiously expand the sanctions on methodically selected foreign banks engaged in Russia’s trade operations.

The ultimate scenario of dealing with the financing of Russia’s war machine would be to recognize Russia as a state sponsor of terrorism and target everyone who maintains economic and political relations with Putin’s regime.

The heinous assassination of popular opposition leader Navalny, the emerging signals that Russia is getting ready to expand its military aggression into Moldova, and the unconstitutional plans of Putin to usurp the power for another term as part of sham elections this March give the West every possible reason to do so.

To make such “secondary” sanctions fully efficient, a comprehensive approach is needed, which is hardly possible because of resistance from such players as China.

The risks are obvious. Nobody wants a full‑scale war in the world’s banking system. Nevertheless, the US has plenty of room to cautiously expand the sanctions on methodically selected foreign banks engaged in Russia’s trade operations.

The ultimate scenario of dealing with the financing of Russia’s war machine would be to recognize Russia as a state sponsor of terrorism and target everyone who maintains economic and political relations with Putin’s regime.

The heinous assassination of popular opposition leader Navalny, the emerging signals that Russia is getting ready to expand its military aggression into Moldova, and the unconstitutional plans of Putin to usurp the power for another term as part of sham elections this March give the West every possible reason to do so.

Vladimir Putin’s corridor of economic opportunities is narrowing

By Vladimir Milov

September 05, 2024

Article

Article Czar Broadcasts Panic

By Vladimir Milov

August 06, 2024

Article

Article Russian dictator threatened by multiple crises, with more to come

By Vladimir Milov

September 07, 2023

Vladimir Putin’s corridor of economic opportunities is narrowing

By Vladimir Milov

September 05, 2024

Article

Article Czar Broadcasts Panic

By Vladimir Milov

August 06, 2024

Article

Article Russian dictator threatened by multiple crises, with more to come

By Vladimir Milov

September 07, 2023