How Georgia Turned Towards the Kremlin

And Cracked Down on Pro‑Western Dissent

By Free Russia Foundation February 05, 2026

And Cracked Down on Pro‑Western Dissent

By Free Russia Foundation February 05, 2026

Over the past decade, Georgia has undergone a profound political and strategic transformation that has largely escaped sustained international scrutiny. Once regarded as a frontline democracy aligned with Euro‑Atlantic institutions and a reliable Western ally, the country has steadily shifted toward political, economic, and security arrangements that increasingly serve Kremlin interests.

At the center of this transformation stands the ruling Georgian Dream party and its founder, Bidzina Ivanishvili, whose informal but decisive influence, funded by the fortune he amassed in Russia, has shaped the country’s trajectory. Under Georgian Dream, democratic safeguards have been progressively weakened while Georgia’s strategic posture has been reoriented away from Euro‑Atlantic integration and toward accommodation with the Kremlin as well as other authoritarian states like China and Iran. What was long presented as “pragmatism” and “de‑escalation” vis‑à-vis Russia has, in practice, functioned as a vehicle for geopolitical reversal.

This paper argues that Georgia’s transformation is not a sudden rupture nor a narrow case of democratic backsliding. It is the outcome of a sustained, deliberate strategy of state capture that has aligned Georgia’s political, security, and economic institutions with Russian interests—without the use of overt military force. Through the capture of the judiciary, the politicization of law enforcement and security services, the suppression of independent media and civil society, and the cultivation of energy and infrastructure dependencies, Georgian Dream has created a governance model that is entirely insulated from democratic accountability and embracing of Kremlin influence.

At the geopolitical level, Georgia’s drift has delivered profound, tangible strategic gains for Moscow. The derailment of Western‑backed infrastructure projects, Georgia’s increasingly well‑documented growing role as a sanctions‑evasion and energy transit hub, and the embrace of pro‑Kremlin extremist networks have weakened the Black Sea nation’s resilience at a critical moment in the war against Ukraine. At the same time, Georgian Dream has distanced itself from Ukraine politically since the early years of its rule and rhetorically, downgraded security cooperation with Western partners, while undermining its own EU accession pathway. Today, Georgian Dream leaders have systematically attacked Ukraine while also accusing the EU and the West of efforts to drag Georgia into war.

Domestically, the state has moved toward systemic repression. Mass and politically selective arrests, prosecutions on fabricated or weakly substantiated charges, police violence, the effective criminalization of peaceful assembly, and the dismantling of civil society organizations and independent media have transformed Georgia’s political system into one increasingly reliant on coercion rather than consent. The scale and intensity of this repression now place Georgia among the most repressive environments in the wider European neighborhood, with political imprisonment and judicial abuse reaching levels comparable to those seen in authoritarian states. A higher per‑capita rate of political prisoners than in Russia itself underscores the depth of this shift.

For the European Union, the United States, and the United Kingdom, Georgia’s trajectory poses a strategic challenge that extends well beyond human rights concerns. It undermines the credibility of EU enlargement, weakens sanctions enforcement against Russia, and signals to other vulnerable states that alignment with Moscow can proceed at limited external cost. Western responses to date have been cautious, fragmented, and insufficient to alter the Georgian government’s calculations.

This paper concludes that the window for preventing Georgia’s consolidation as a durable Kremlin client state has not yet closed—but it is narrowing. It outlines a set of targeted, coordinated policy measures for the EU, the United States, the United Kingdom and international institutions aimed at restoring leverage, imposing accountability on those responsible for repression and alignment with Russia, helping Georgian civil society and independent media to survive, and reaffirming that democratic regression and strategic realignment carry real consequences. Georgian society has shown remarkable resilience in the face of frontal and overwhelming repression and these measures are necessary to recognize that sacrifice and help reverse Georgia’s course, because only Georgian society can do so. Georgia’s future, and the credibility of Western engagement in the post‑Soviet space, will depend on whether these tools are used decisively.

Over the past decade, Georgia has undergone a profound political and strategic transformation that has largely escaped sustained international scrutiny. Once regarded as a frontline democracy aligned with Euro‑Atlantic institutions and a reliable Western ally, the country has steadily shifted toward political, economic, and security arrangements that increasingly serve Kremlin interests.

At the center of this transformation stands the ruling Georgian Dream party and its founder, Bidzina Ivanishvili, whose informal but decisive influence, funded by the fortune he amassed in Russia, has shaped the country’s trajectory. Under Georgian Dream, democratic safeguards have been progressively weakened while Georgia’s strategic posture has been reoriented away from Euro‑Atlantic integration and toward accommodation with the Kremlin as well as other authoritarian states like China and Iran. What was long presented as “pragmatism” and “de‑escalation” vis‑à-vis Russia has, in practice, functioned as a vehicle for geopolitical reversal.

This paper argues that Georgia’s transformation is not a sudden rupture nor a narrow case of democratic backsliding. It is the outcome of a sustained, deliberate strategy of state capture that has aligned Georgia’s political, security, and economic institutions with Russian interests—without the use of overt military force. Through the capture of the judiciary, the politicization of law enforcement and security services, the suppression of independent media and civil society, and the cultivation of energy and infrastructure dependencies, Georgian Dream has created a governance model that is entirely insulated from democratic accountability and embracing of Kremlin influence.

At the geopolitical level, Georgia’s drift has delivered profound, tangible strategic gains for Moscow. The derailment of Western‑backed infrastructure projects, Georgia’s increasingly well‑documented growing role as a sanctions‑evasion and energy transit hub, and the embrace of pro‑Kremlin extremist networks have weakened the Black Sea nation’s resilience at a critical moment in the war against Ukraine. At the same time, Georgian Dream has distanced itself from Ukraine politically since the early years of its rule and rhetorically, downgraded security cooperation with Western partners, while undermining its own EU accession pathway. Today, Georgian Dream leaders have systematically attacked Ukraine while also accusing the EU and the West of efforts to drag Georgia into war.

Domestically, the state has moved toward systemic repression. Mass and politically selective arrests, prosecutions on fabricated or weakly substantiated charges, police violence, the effective criminalization of peaceful assembly, and the dismantling of civil society organizations and independent media have transformed Georgia’s political system into one increasingly reliant on coercion rather than consent. The scale and intensity of this repression now place Georgia among the most repressive environments in the wider European neighborhood, with political imprisonment and judicial abuse reaching levels comparable to those seen in authoritarian states. A higher per‑capita rate of political prisoners than in Russia itself underscores the depth of this shift.

For the European Union, the United States, and the United Kingdom, Georgia’s trajectory poses a strategic challenge that extends well beyond human rights concerns. It undermines the credibility of EU enlargement, weakens sanctions enforcement against Russia, and signals to other vulnerable states that alignment with Moscow can proceed at limited external cost. Western responses to date have been cautious, fragmented, and insufficient to alter the Georgian government’s calculations.

This paper concludes that the window for preventing Georgia’s consolidation as a durable Kremlin client state has not yet closed—but it is narrowing. It outlines a set of targeted, coordinated policy measures for the EU, the United States, the United Kingdom and international institutions aimed at restoring leverage, imposing accountability on those responsible for repression and alignment with Russia, helping Georgian civil society and independent media to survive, and reaffirming that democratic regression and strategic realignment carry real consequences. Georgian society has shown remarkable resilience in the face of frontal and overwhelming repression and these measures are necessary to recognize that sacrifice and help reverse Georgia’s course, because only Georgian society can do so. Georgia’s future, and the credibility of Western engagement in the post‑Soviet space, will depend on whether these tools are used decisively.

The prevailing narrative in Western political and policy circles has long held that, after coming to power in 2012, the Georgian Dream party—founded and bankrolled by billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili, whose personal Russia‑amassed fortune that year exceeded one‑third of Georgia’s GDP—broadly continued the pro‑Western, democratic trajectory launched by the 2003 Rose Revolution. According to this view, Georgia overall remained on the “right path” until a sudden and surprising authoritarian turn in 2024.

This comfortable interpretation, however, obscures a far more gradual and systematic process of democratic erosion, state capture and geopolitical realignment. It was reinforced by the broader geopolitical context. Western capitals, notably the Obama administration’s “reset” policy with Russia—which effectively gave Moscow a pass for its 2008 invasion of Georgia—and Angela Merkel’s government, which had blocked NATO Membership Action Plans for Georgia and Ukraine at the 2008 Bucharest summit, prioritized “stability” over confrontation with Moscow.

In this environment, the new Georgian Dream government rhetorically reaffirmed NATO and EU integration while quietly disengaging from the political work required to advance it. For over a decade, Georgian Dream’s rhetorical continuity and procedural box‑ticking compelled Western—particularly EU—officials to maintain the convenient fiction of steady democratic progress, even as evidence for gradual state capture and the growth of the Kremlin influence slowly piled up.

Fast forward to December 2024, the United States sanctioned Mr. Ivanishvili under Executive Order 14024, a framework explicitly designed to target individuals and entities advancing the Russian Federation's “specified harmful foreign activities,” Daniel Fried, former U.S. State Department sanctions coordinator, told Voice of America on January 5 that the order applies to “Russian agents or individuals acting in Russia’s interests.”

The prevailing narrative in Western political and policy circles has long held that, after coming to power in 2012, the Georgian Dream party—founded and bankrolled by billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili, whose personal Russia‑amassed fortune that year exceeded one‑third of Georgia’s GDP—broadly continued the pro‑Western, democratic trajectory launched by the 2003 Rose Revolution. According to this view, Georgia overall remained on the “right path” until a sudden and surprising authoritarian turn in 2024.

This comfortable interpretation, however, obscures a far more gradual and systematic process of democratic erosion, state capture and geopolitical realignment. It was reinforced by the broader geopolitical context. Western capitals, notably the Obama administration’s “reset” policy with Russia—which effectively gave Moscow a pass for its 2008 invasion of Georgia—and Angela Merkel’s government, which had blocked NATO Membership Action Plans for Georgia and Ukraine at the 2008 Bucharest summit, prioritized “stability” over confrontation with Moscow.

In this environment, the new Georgian Dream government rhetorically reaffirmed NATO and EU integration while quietly disengaging from the political work required to advance it. For over a decade, Georgian Dream’s rhetorical continuity and procedural box‑ticking compelled Western—particularly EU—officials to maintain the convenient fiction of steady democratic progress, even as evidence for gradual state capture and the growth of the Kremlin influence slowly piled up.

Fast forward to December 2024, the United States sanctioned Mr. Ivanishvili under Executive Order 14024, a framework explicitly designed to target individuals and entities advancing the Russian Federation's “specified harmful foreign activities,” Daniel Fried, former U.S. State Department sanctions coordinator, told Voice of America on January 5 that the order applies to “Russian agents or individuals acting in Russia’s interests.”

“This means the United States has evidence of Ivanishvili’s actions on behalf of the Kremlin.”

“This means the United States has evidence of Ivanishvili’s actions on behalf of the Kremlin.”

As of December 2025, these sanctions remain firmly in force under the Trump administration, despite vehement complaints from Georgian Dream leaders with no foreseeable plans for removal absent a fundamental policy reversal by Tbilisi.

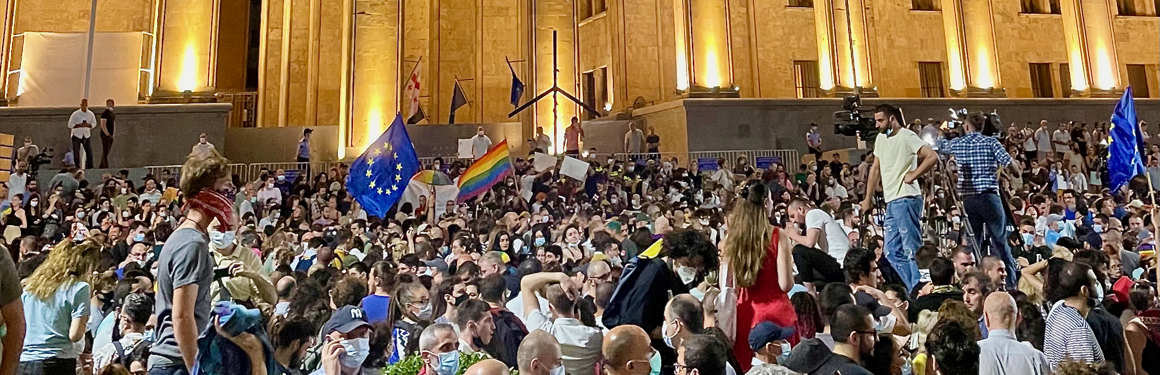

A year after Georgian Dream’s fateful decision to unilaterally halt Georgia’s EU integration—and the eruption of nationwide protests—Georgia finds itself more isolated from the West than at any point since 1991. Per capita, the country now holds more political prisoners than Russia. Waves of violent crackdowns have left hundreds of protesters injured, and credible reports have emerged suggesting the possible use of banned chemical agents against demonstrators. Despite all this, the protests continue without interruption daily for more than a year.

In the face of this defiance, the regime has tightened the screws even further, cracking down on freedom of expression and, in practice more reminiscent of Russia and Belarus, sending protestors to jail simply for standing on Rustaveli avenue. The latest amendments, rushed through parliament under expedited procedures at the time of writing, would impose up to 15 days’ detention—and up to one year in prison for a repeated offense—for “obstructing pedestrian traffic,” a definition broad enough to criminalize standing on a sidewalk. The United States has suspended the Strategic Partnership Charter launched in 2009. While EU sanctions have been thwarted by Hungarian obstruction, Georgian Dream has been politically ostracized by Brussels. In parallel, senior Russian officials have publicly and repeatedly rallied behind the ruling party.

As of December 2025, these sanctions remain firmly in force under the Trump administration, despite vehement complaints from Georgian Dream leaders with no foreseeable plans for removal absent a fundamental policy reversal by Tbilisi.

A year after Georgian Dream’s fateful decision to unilaterally halt Georgia’s EU integration—and the eruption of nationwide protests—Georgia finds itself more isolated from the West than at any point since 1991. Per capita, the country now holds more political prisoners than Russia. Waves of violent crackdowns have left hundreds of protesters injured, and credible reports have emerged suggesting the possible use of banned chemical agents against demonstrators. Despite all this, the protests continue without interruption daily for more than a year.

In the face of this defiance, the regime has tightened the screws even further, cracking down on freedom of expression and, in practice more reminiscent of Russia and Belarus, sending protestors to jail simply for standing on Rustaveli avenue. The latest amendments, rushed through parliament under expedited procedures at the time of writing, would impose up to 15 days’ detention—and up to one year in prison for a repeated offense—for “obstructing pedestrian traffic,” a definition broad enough to criminalize standing on a sidewalk. The United States has suspended the Strategic Partnership Charter launched in 2009. While EU sanctions have been thwarted by Hungarian obstruction, Georgian Dream has been politically ostracized by Brussels. In parallel, senior Russian officials have publicly and repeatedly rallied behind the ruling party.

Georgian Dream has achieved narrative convergence with Russian propaganda, framing the west and especially the European Union as destabilizing and pushing Georgia towards war, NGOs as “foreign controlled” and “agents.” In short, Georgia consistently does what the Kremlin needs, producing outcomes converging with Moscow’s interests through domestic decisions, legal instruments and rhetoric, minimizing overt fingerprints.

This report seeks to trace Georgia’s drift away from the West, assess the scope of Kremlin influence, and examine the domestic governance model that underpins this alignment. Answering these questions is essential to formulating a credible policy that genuinely supports the Georgian people, prevents a geopolitical victory for Russia, and averts a strategic defeat for both Georgia and the West. As the first paper of a two‑part series, this one focuses on the strategic and institutional dimensions of Georgia’s realignment, while the second paper provides a detailed analysis of political imprisonment and the system of repression that enforces it.

Georgian Dream has achieved narrative convergence with Russian propaganda, framing the west and especially the European Union as destabilizing and pushing Georgia towards war, NGOs as “foreign controlled” and “agents.” In short, Georgia consistently does what the Kremlin needs, producing outcomes converging with Moscow’s interests through domestic decisions, legal instruments and rhetoric, minimizing overt fingerprints.

This report seeks to trace Georgia’s drift away from the West, assess the scope of Kremlin influence, and examine the domestic governance model that underpins this alignment. Answering these questions is essential to formulating a credible policy that genuinely supports the Georgian people, prevents a geopolitical victory for Russia, and averts a strategic defeat for both Georgia and the West. As the first paper of a two‑part series, this one focuses on the strategic and institutional dimensions of Georgia’s realignment, while the second paper provides a detailed analysis of political imprisonment and the system of repression that enforces it.

Georgia’s strategic disengagement from the West did not begin with overt repression or formal policy reversals. It began with a quieter shift, framed as “pragmatism,” that deprioritized Georgia’s alignment with Western security and political objectives and prioritized allowing Russia to rebuild its leverages and influence inside Georgia in various spheres. Nowhere was this more visible—or more consequential—than in Georgia’s posture toward Ukraine after 2014.

As early as 2014, when Russia launched its first invasion of Ukraine and annexed Crimea, Georgia’s then‑Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili firmly rejected any parallels with the 2008 war against his own country. He declared that Tbilisi was pursuing a “pragmatic policy” toward Moscow and suggested that Ukraine should learn from Georgia’s example. This framing resonated strongly in parts of Western Europe, where policymakers were eager to restore business as usual with Russia through initiatives such as the “modernization partnership” and, later, Nord Stream 2. An assertive Georgian campaign for NATO membership would have been an unwelcome complication in this environment.

Militarily, Georgia continued to participate in NATO exercises and maintained close operational ties with the United States. Politically, however, the question of making progress on NATO membership was quietly shelved. Georgian Dream repeatedly and explicitly disavowed pressure on the politically costly question of enlargement, signaling de facto acceptance of a frozen trajectory.

The distancing from Ukraine followed a similarly deliberate pattern. Georgia and Ukraine had long been viewed as a single political and strategic package in any prospective expansion of Euro‑Atlantic institutions. Both sought NATO Membership Action Plans in 2008; both faced Russian military aggression in response. After Ukraine’s Revolution of Dignity and the launch of the Russia’s renewed aggression in 2014, however, the Georgian Government consistently avoided political alignment with Kyiv and deliberately downgraded bilateral relations with Ukraine. No Georgian Prime Minister has visited Ukraine in bilateral capacity since Georgian Dream came to power in 2012, even during Yanukovich’s time in office. The government also declined to leverage international attention on Ukraine to re‑center discussion of Russia’s occupation of Georgian territory within Western policy debates.

Equally consequential was Georgia’s refusal to back its allies, such as the Baltic States, Poland, and indeed Ukraine, to oppose, or meaningfully contest, Germany’s push for the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, despite its clear implications for European energy dependence on Russia and for the strategic marginalization of Eastern European security concerns.

Russia’s gain from this disengagement was straightforward. A frontline state that might otherwise have amplified pressure on Moscow—drawing sustained attention to Russian occupation, coercion, and escalation—was effectively neutralized. The traditional political alignment between Georgia and Ukraine, which could have served as a powerful anchor for sustained Western attention and solidarity, was weakened at a critical moment.

By abandoning sustained political advocacy, Georgia eroded the leverage derived from its own 2008 experience and forfeited the opportunity to embed its security narrative firmly within Western strategic priorities.

Georgia’s strategic disengagement from the West did not begin with overt repression or formal policy reversals. It began with a quieter shift, framed as “pragmatism,” that deprioritized Georgia’s alignment with Western security and political objectives and prioritized allowing Russia to rebuild its leverages and influence inside Georgia in various spheres. Nowhere was this more visible—or more consequential—than in Georgia’s posture toward Ukraine after 2014.

As early as 2014, when Russia launched its first invasion of Ukraine and annexed Crimea, Georgia’s then‑Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili firmly rejected any parallels with the 2008 war against his own country. He declared that Tbilisi was pursuing a “pragmatic policy” toward Moscow and suggested that Ukraine should learn from Georgia’s example. This framing resonated strongly in parts of Western Europe, where policymakers were eager to restore business as usual with Russia through initiatives such as the “modernization partnership” and, later, Nord Stream 2. An assertive Georgian campaign for NATO membership would have been an unwelcome complication in this environment.

Militarily, Georgia continued to participate in NATO exercises and maintained close operational ties with the United States. Politically, however, the question of making progress on NATO membership was quietly shelved. Georgian Dream repeatedly and explicitly disavowed pressure on the politically costly question of enlargement, signaling de facto acceptance of a frozen trajectory.

The distancing from Ukraine followed a similarly deliberate pattern. Georgia and Ukraine had long been viewed as a single political and strategic package in any prospective expansion of Euro‑Atlantic institutions. Both sought NATO Membership Action Plans in 2008; both faced Russian military aggression in response. After Ukraine’s Revolution of Dignity and the launch of the Russia’s renewed aggression in 2014, however, the Georgian Government consistently avoided political alignment with Kyiv and deliberately downgraded bilateral relations with Ukraine. No Georgian Prime Minister has visited Ukraine in bilateral capacity since Georgian Dream came to power in 2012, even during Yanukovich’s time in office. The government also declined to leverage international attention on Ukraine to re‑center discussion of Russia’s occupation of Georgian territory within Western policy debates.

Equally consequential was Georgia’s refusal to back its allies, such as the Baltic States, Poland, and indeed Ukraine, to oppose, or meaningfully contest, Germany’s push for the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, despite its clear implications for European energy dependence on Russia and for the strategic marginalization of Eastern European security concerns.

Russia’s gain from this disengagement was straightforward. A frontline state that might otherwise have amplified pressure on Moscow—drawing sustained attention to Russian occupation, coercion, and escalation—was effectively neutralized. The traditional political alignment between Georgia and Ukraine, which could have served as a powerful anchor for sustained Western attention and solidarity, was weakened at a critical moment.

By abandoning sustained political advocacy, Georgia eroded the leverage derived from its own 2008 experience and forfeited the opportunity to embed its security narrative firmly within Western strategic priorities.

A central mechanism through which Georgian Dream aligned Georgia’s political system with Kremlin interests was the deliberate re‑engineering of the political field itself. Rather than relying solely on repression from above, the regime cultivated a permissive ecosystem of openly pro‑Kremlin actors—political parties, media outlets, and violent groups—while shielding them from accountability, effectively granting them impunity. This strategy created what can best be described as “strategic depth” inside Georgia’s domestic political arena: an outer layer of radical, Kremlin‑aligned forces that normalized pro‑Russian narratives, intimidated civil society, and made the government’s own trajectory appear comparatively moderate.

From early on, Mr Ivanishvili has repeatedly endorsed openly pro‑Kremlin extremist parties, providing them political cover and, in some cases, direct support. One of its leaders, Emzar Kvitsiani, previously a warlord who rebelled against Georgia with his armed militia in 2006, fled to Russia, and lived there between 2006 and 2013 while reportedly on the payroll of the Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB).

In parallel, multiple authoritative assessments, including annual reports by the European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance, documented government‑linked funding and protection of pro‑Russian media outlets engaged in hate speech and anti‑Western messaging. Chief among these was Obieqtivi TV, a flagship pro‑Russian and anti‑Western broadcaster directly affiliated with the Alliance of Patriots. Rather than marginalizing these actors, Georgian Dream integrated them into the broader information environment, allowing Kremlin narratives to circulate with increasing legitimacy, pushing them from margins of the public discourse to the mainstream.

A pivotal escalation occurred in June 2019, when Russian Communist MP Sergey Gavrilov was permitted to enter Georgia and take the speaker’s chair in the Georgian Parliament while presiding over the Inter‑Parliamentary Assembly of Orthodoxy, an international platform widely regarded as a vehicle for Kremlin influence. Gavrilov’s presence, given his prior role in Abkhazia during the 1992–1993 ethnic cleansing of Georgians and his advisory work for Saddam Hussein, sparked mass protests and marked the first major popular challenge to Georgian Dream’s hold on power.

Following the protests, a coordinated disinformation campaign—drawing on pro‑government, pro‑Russian, and extremist online networks—sought to delegitimize the demonstrators and reframe the protests as destabilizing and foreign‑driven. As documented by the Media Development Foundation, this campaign relied heavily on troll networks and aligned media platforms, underscoring the convergence between government messaging and Russian information tactics.

The most violent manifestation of this ecosystem emerged on July 5, 2021, when the openly Putinist, Georgian Dream‑aligned group Alt Info orchestrated attacks on participants in a planned Pride march and on journalists covering the event. The violence—widely described by Georgian civil society and media as a coordinated pogrom—left more than 50 journalists beaten, including TV Pirveli cameraman Lekso Lashkarava, who later died from severe head and facial injuries.

A central mechanism through which Georgian Dream aligned Georgia’s political system with Kremlin interests was the deliberate re‑engineering of the political field itself. Rather than relying solely on repression from above, the regime cultivated a permissive ecosystem of openly pro‑Kremlin actors—political parties, media outlets, and violent groups—while shielding them from accountability, effectively granting them impunity. This strategy created what can best be described as “strategic depth” inside Georgia’s domestic political arena: an outer layer of radical, Kremlin‑aligned forces that normalized pro‑Russian narratives, intimidated civil society, and made the government’s own trajectory appear comparatively moderate.

From early on, Mr Ivanishvili has repeatedly endorsed openly pro‑Kremlin extremist parties, providing them political cover and, in some cases, direct support. One of its leaders, Emzar Kvitsiani, previously a warlord who rebelled against Georgia with his armed militia in 2006, fled to Russia, and lived there between 2006 and 2013 while reportedly on the payroll of the Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB).

In parallel, multiple authoritative assessments, including annual reports by the European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance, documented government‑linked funding and protection of pro‑Russian media outlets engaged in hate speech and anti‑Western messaging. Chief among these was Obieqtivi TV, a flagship pro‑Russian and anti‑Western broadcaster directly affiliated with the Alliance of Patriots. Rather than marginalizing these actors, Georgian Dream integrated them into the broader information environment, allowing Kremlin narratives to circulate with increasing legitimacy, pushing them from margins of the public discourse to the mainstream.

A pivotal escalation occurred in June 2019, when Russian Communist MP Sergey Gavrilov was permitted to enter Georgia and take the speaker’s chair in the Georgian Parliament while presiding over the Inter‑Parliamentary Assembly of Orthodoxy, an international platform widely regarded as a vehicle for Kremlin influence. Gavrilov’s presence, given his prior role in Abkhazia during the 1992–1993 ethnic cleansing of Georgians and his advisory work for Saddam Hussein, sparked mass protests and marked the first major popular challenge to Georgian Dream’s hold on power.

Following the protests, a coordinated disinformation campaign—drawing on pro‑government, pro‑Russian, and extremist online networks—sought to delegitimize the demonstrators and reframe the protests as destabilizing and foreign‑driven. As documented by the Media Development Foundation, this campaign relied heavily on troll networks and aligned media platforms, underscoring the convergence between government messaging and Russian information tactics.

The most violent manifestation of this ecosystem emerged on July 5, 2021, when the openly Putinist, Georgian Dream‑aligned group Alt Info orchestrated attacks on participants in a planned Pride march and on journalists covering the event. The violence—widely described by Georgian civil society and media as a coordinated pogrom—left more than 50 journalists beaten, including TV Pirveli cameraman Lekso Lashkarava, who later died from severe head and facial injuries.

Subsequent investigations by Georgian media revealed that Alt Info played a central role in organizing the violence. Further reporting indicated that Georgia’s State Security Service not only failed to prevent the attacks but actively planned and coordinated aspects of the July 5 violent operation. In response, ten of Georgia’s most credible civil society organizations demanded an immediate and effective investigation, warning that the evidence raised the “dangerous and alarming possibility” that state security structures were directly involved in managing mass violence.” Despite sustained domestic and international pressure—including demands from the EU and the United States—no organizers have been held accountable to date.

Instead, investigative reporting revealed systemic preferential treatment for Alt Info leaders, including illegal construction permits, preferential access to mineral extraction licenses, and other financial benefits. One of the group’s leaders, Zura Morgoshia, later confirmed plans to launch a construction business in Russia. Credible Georgian watchdog organizations also documented systematic acts of physical violence committed by members of Alt Info, including assaults on participants in pro‑Ukrainian rallies, carried out under conditions of near‑total impunity. Morgoshia was eventually sanctioned by the United States Treasury, alongside Georgian Interior Ministry officials complicit in the brutal suppression of democratic protest.

In strategic terms, this pattern of selective empowerment served a clear function. By cultivating a radicalized outer ring of pro‑Kremlin actors while repressing pro‑Western opposition, Georgian Dream enabled Moscow to expand its influence without overt intervention. The presence of extremist groups normalized pro‑Russian rhetoric, intimidated journalists and minorities, and shifted the political center of gravity—allowing the government’s own concessions to Moscow to appear restrained by comparison.

For Russia, the benefit was substantial: a domestically embedded influence network capable of shaping narratives, mobilizing violence, and applying pressure at minimal cost and with plausible deniability. For Georgia, the cost was severe. The political playing field was poisoned, violence against journalists and minorities was normalized, law enforcement was further politicized, and openly Kremlin‑aligned actors gained unprecedented visibility and protection from the state.

Elite Protection and Informal Power: The Partskhaladze Case

Otar Partskhaladze, a former Prosecutor General and long‑time informal power broker within the system built by Bidzina Ivanishvili, offers a revealing case study of how Georgian state institutions have been mobilized to protect Kremlin‑aligned interests. Although Partskhaladze’s formal tenure in public office was brief, his influence endured for years through informal channels closely tied to Ivanishvili’s inner circle. In September 2023, the United States sanctioned Partskhaladze for acting as a vehicle of Russian influence in Georgia, citing cooperation with the FSB, acquisition of Russian citizenship with intelligence assistance, and sustained engagement with Russian state‑linked networks.

Rather than distancing itself from an individual publicly identified by Western partners as a Russian asset, the Georgian government moved decisively to shield him. Most notably, the National Bank of Georgia amended its internal regulations to prevent enforcement of U.S. sanctions—a step that prompted the resignation of senior central bank officials and underscored the extent to which formally independent institutions had been subordinated to political imperatives. In 2025, the United Kingdom imposed parallel sanctions.

Even though Partskhaladze has fallen out with Ivanishvili recently, his direct linkage with Ivanishvili and the protection afforded to Partskhaladze stands in stark contrast to the systematic prosecution of Georgia’s pro‑Western political opposition and civil society. Since 2023—and with particular intensity in 2024—this approach has escalated into an explicit strategy of political neutralization. During the 2024 campaign, Ivanishvili publicly pledged to dismantle what he termed the “collective opposition,” framing political pluralism itself as a threat to state security.

This juxtaposition is instructive. While state institutions were rapidly reconfigured to shield an individual sanctioned for advancing Russian interests, the same apparatus was deployed aggressively against pro‑European actors. Repression, in this context, is not a deviation from governance norms but a functional component of a system designed to protect Kremlin‑aligned networks while dismantling domestic democratic resistance to that alignment. The Partskhaladze case thus illustrates how informal power, institutional capture, and selective enforcement have converged to embed Russian influence deep within Georgia’s political architecture.

Aligning with Kremlin Red Lines: Excluding Russian Democratic Opposition

Georgia’s internal repression has unfolded alongside a systematic policy of denying entry to, or deporting, prominent and lesser‑known Russian democratic opposition figures—effectively aligning Georgian practice with Kremlin red lines beyond Russia’s borders. In August 2021, Lyubov Sobol, a leading associate of Alexei Navalny, was refused entry at the Georgia–Armenia border without explanation. In January 2022, Dmitry Gudkov was detained upon arrival in Tbilisi and deported to Kyiv; days later, another Russian opposition activist was turned away under similar circumstances. In February 2023, Anna Rivina, founder of a prominent Russian NGO assisting survivors of domestic violence, was denied re‑entry to Georgia after residing in Tbilisi for nearly a year.

By systematically barring well‑known Kremlin critics, Georgian authorities curtailed the country’s role as a safe rear base for Russian democratic opposition and clearly signaled de facto compliance with Moscow’s extraterritorial preferences. For Russia, the gain was tangible: reduced operating space for its critics abroad and reinforcement of efforts to isolate opposition figures beyond its borders.

For Georgia, the exclusions eroded the country’s long‑standing reputation as a haven for political exiles and unfolded in parallel with the intensifying repression of Georgia’s own pro‑Western opposition and reinforced the growing image of the Georgian Dream as a de facto Russian proxy. This convergence underscores a broader realignment: domestic authoritarian consolidation paired with foreign‑policy accommodation of Kremlin interests, achieved without a formal alliance but through consistent, mutually reinforcing choices.

Subsequent investigations by Georgian media revealed that Alt Info played a central role in organizing the violence. Further reporting indicated that Georgia’s State Security Service not only failed to prevent the attacks but actively planned and coordinated aspects of the July 5 violent operation. In response, ten of Georgia’s most credible civil society organizations demanded an immediate and effective investigation, warning that the evidence raised the “dangerous and alarming possibility” that state security structures were directly involved in managing mass violence.” Despite sustained domestic and international pressure—including demands from the EU and the United States—no organizers have been held accountable to date.

Instead, investigative reporting revealed systemic preferential treatment for Alt Info leaders, including illegal construction permits, preferential access to mineral extraction licenses, and other financial benefits. One of the group’s leaders, Zura Morgoshia, later confirmed plans to launch a construction business in Russia. Credible Georgian watchdog organizations also documented systematic acts of physical violence committed by members of Alt Info, including assaults on participants in pro‑Ukrainian rallies, carried out under conditions of near‑total impunity. Morgoshia was eventually sanctioned by the United States Treasury, alongside Georgian Interior Ministry officials complicit in the brutal suppression of democratic protest.

In strategic terms, this pattern of selective empowerment served a clear function. By cultivating a radicalized outer ring of pro‑Kremlin actors while repressing pro‑Western opposition, Georgian Dream enabled Moscow to expand its influence without overt intervention. The presence of extremist groups normalized pro‑Russian rhetoric, intimidated journalists and minorities, and shifted the political center of gravity—allowing the government’s own concessions to Moscow to appear restrained by comparison.

For Russia, the benefit was substantial: a domestically embedded influence network capable of shaping narratives, mobilizing violence, and applying pressure at minimal cost and with plausible deniability. For Georgia, the cost was severe. The political playing field was poisoned, violence against journalists and minorities was normalized, law enforcement was further politicized, and openly Kremlin‑aligned actors gained unprecedented visibility and protection from the state.

Elite Protection and Informal Power: The Partskhaladze Case

Otar Partskhaladze, a former Prosecutor General and long‑time informal power broker within the system built by Bidzina Ivanishvili, offers a revealing case study of how Georgian state institutions have been mobilized to protect Kremlin‑aligned interests. Although Partskhaladze’s formal tenure in public office was brief, his influence endured for years through informal channels closely tied to Ivanishvili’s inner circle. In September 2023, the United States sanctioned Partskhaladze for acting as a vehicle of Russian influence in Georgia, citing cooperation with the FSB, acquisition of Russian citizenship with intelligence assistance, and sustained engagement with Russian state‑linked networks.

Rather than distancing itself from an individual publicly identified by Western partners as a Russian asset, the Georgian government moved decisively to shield him. Most notably, the National Bank of Georgia amended its internal regulations to prevent enforcement of U.S. sanctions—a step that prompted the resignation of senior central bank officials and underscored the extent to which formally independent institutions had been subordinated to political imperatives. In 2025, the United Kingdom imposed parallel sanctions.

Even though Partskhaladze has fallen out with Ivanishvili recently, his direct linkage with Ivanishvili and the protection afforded to Partskhaladze stands in stark contrast to the systematic prosecution of Georgia’s pro‑Western political opposition and civil society. Since 2023—and with particular intensity in 2024—this approach has escalated into an explicit strategy of political neutralization. During the 2024 campaign, Ivanishvili publicly pledged to dismantle what he termed the “collective opposition,” framing political pluralism itself as a threat to state security.

This juxtaposition is instructive. While state institutions were rapidly reconfigured to shield an individual sanctioned for advancing Russian interests, the same apparatus was deployed aggressively against pro‑European actors. Repression, in this context, is not a deviation from governance norms but a functional component of a system designed to protect Kremlin‑aligned networks while dismantling domestic democratic resistance to that alignment. The Partskhaladze case thus illustrates how informal power, institutional capture, and selective enforcement have converged to embed Russian influence deep within Georgia’s political architecture.

Aligning with Kremlin Red Lines: Excluding Russian Democratic Opposition

Georgia’s internal repression has unfolded alongside a systematic policy of denying entry to, or deporting, prominent and lesser‑known Russian democratic opposition figures—effectively aligning Georgian practice with Kremlin red lines beyond Russia’s borders. In August 2021, Lyubov Sobol, a leading associate of Alexei Navalny, was refused entry at the Georgia–Armenia border without explanation. In January 2022, Dmitry Gudkov was detained upon arrival in Tbilisi and deported to Kyiv; days later, another Russian opposition activist was turned away under similar circumstances. In February 2023, Anna Rivina, founder of a prominent Russian NGO assisting survivors of domestic violence, was denied re‑entry to Georgia after residing in Tbilisi for nearly a year.

By systematically barring well‑known Kremlin critics, Georgian authorities curtailed the country’s role as a safe rear base for Russian democratic opposition and clearly signaled de facto compliance with Moscow’s extraterritorial preferences. For Russia, the gain was tangible: reduced operating space for its critics abroad and reinforcement of efforts to isolate opposition figures beyond its borders.

For Georgia, the exclusions eroded the country’s long‑standing reputation as a haven for political exiles and unfolded in parallel with the intensifying repression of Georgia’s own pro‑Western opposition and reinforced the growing image of the Georgian Dream as a de facto Russian proxy. This convergence underscores a broader realignment: domestic authoritarian consolidation paired with foreign‑policy accommodation of Kremlin interests, achieved without a formal alliance but through consistent, mutually reinforcing choices.

Parallel to the engineering of the political field, Georgian Dream undertook a systematic degradation of Georgia’s security and counterintelligence architecture—quietly dismantling the state’s capacity to detect, deter, and disrupt Russian intelligence activity. This process preceded the visible authoritarian turn and functioned as a critical enabler of Georgia’s broader political capture.

While vigilance toward Russian intelligence operations intensified across NATO members and partner states following Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, Georgia moved in the opposite direction. Since 2012, there has not been a single case of apprehending a Russian spy on Georgian territory. Already in 2013, the Georgian Dream government released virtually all individuals imprisoned for espionage on behalf of Russia, including Russian citizens with documented links to the Russian military intelligence (the GRU), without declassifying their cases. No reciprocal demands were made for the release of individuals detained in Russia for activities conducted in Georgia’s interest.

Parallel to the engineering of the political field, Georgian Dream undertook a systematic degradation of Georgia’s security and counterintelligence architecture—quietly dismantling the state’s capacity to detect, deter, and disrupt Russian intelligence activity. This process preceded the visible authoritarian turn and functioned as a critical enabler of Georgia’s broader political capture.

While vigilance toward Russian intelligence operations intensified across NATO members and partner states following Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, Georgia moved in the opposite direction. Since 2012, there has not been a single case of apprehending a Russian spy on Georgian territory. Already in 2013, the Georgian Dream government released virtually all individuals imprisoned for espionage on behalf of Russia, including Russian citizens with documented links to the Russian military intelligence (the GRU), without declassifying their cases. No reciprocal demands were made for the release of individuals detained in Russia for activities conducted in Georgia’s interest.

Among those released were members of the deep‑cover GRU network uncovered in 2010 during the high‑profile counterintelligence operation codenamed “Enver.” The decision to free convicted Russian intelligence operatives sent an early and unambiguous signal: the Russian intelligence threat would no longer be treated as a priority.

At the same time, experienced counterintelligence officers, many of whom had undergone extensive U.S. training and played key roles in bilateral security cooperation—were removed from office or prosecuted. According to the former Minister of Defense Irakli Alasania, who served in the Georgian Dream government from 2012 to 2016, the security services received explicit instructions to deprioritize the Russian direction. This shift marked a fundamental break with Georgia’s post‑2008 security posture as a frontline state exposed to ongoing Russian occupation.

Independent assessments reinforce this conclusion. Former Soviet KGB officers and individuals loyal to Russian special services were reintegrated into Georgia’s security apparatus after Georgian Dream came to power. Examples include Mirian Mchedlishvili, Deputy Chief of the State Security Service between 2015–2018, who previously served as Chief of the Agitation and Propaganda Department of the Communist Party and as an instructor at the Communist Party’s Central Committee in the 1980s, as well as Shengeli Pitskhelauri, another senior security official.

The cumulative effect of these personnel and policy decisions went far beyond bureaucratic drift and amounted to a strategic dismantlement of Georgia’s security architecture. By releasing convicted Russian spies, purging trained counterintelligence professionals, rehabilitating figures with Soviet and Russian security ties, and systematically deprioritizing the Russian threat, Georgian Dream neutralized the country’s first line of defense against hostile penetration. For Moscow, the result was immediate and tangible: a former frontline state once deeply integrated into Western security cooperation was transformed into permissive terrain for Russian intelligence operations, marked by the absence of arrests, investigations, or public exposure of Russian espionage activity. This environment of near‑total impunity stood in sharp contrast to the heightened vigilance across NATO and allied states and materially enabled Russia’s broader political and institutional capture of Georgia.

The erosion of Georgia’s security apparatus thus preceded—and facilitated—the country’s broader authoritarian turn. By the time repression became overt, the institutional safeguards that might have resisted or constrained Russian influence had already been dismantled.

Among those released were members of the deep‑cover GRU network uncovered in 2010 during the high‑profile counterintelligence operation codenamed “Enver.” The decision to free convicted Russian intelligence operatives sent an early and unambiguous signal: the Russian intelligence threat would no longer be treated as a priority.

At the same time, experienced counterintelligence officers, many of whom had undergone extensive U.S. training and played key roles in bilateral security cooperation—were removed from office or prosecuted. According to the former Minister of Defense Irakli Alasania, who served in the Georgian Dream government from 2012 to 2016, the security services received explicit instructions to deprioritize the Russian direction. This shift marked a fundamental break with Georgia’s post‑2008 security posture as a frontline state exposed to ongoing Russian occupation.

Independent assessments reinforce this conclusion. Former Soviet KGB officers and individuals loyal to Russian special services were reintegrated into Georgia’s security apparatus after Georgian Dream came to power. Examples include Mirian Mchedlishvili, Deputy Chief of the State Security Service between 2015–2018, who previously served as Chief of the Agitation and Propaganda Department of the Communist Party and as an instructor at the Communist Party’s Central Committee in the 1980s, as well as Shengeli Pitskhelauri, another senior security official.

The cumulative effect of these personnel and policy decisions went far beyond bureaucratic drift and amounted to a strategic dismantlement of Georgia’s security architecture. By releasing convicted Russian spies, purging trained counterintelligence professionals, rehabilitating figures with Soviet and Russian security ties, and systematically deprioritizing the Russian threat, Georgian Dream neutralized the country’s first line of defense against hostile penetration. For Moscow, the result was immediate and tangible: a former frontline state once deeply integrated into Western security cooperation was transformed into permissive terrain for Russian intelligence operations, marked by the absence of arrests, investigations, or public exposure of Russian espionage activity. This environment of near‑total impunity stood in sharp contrast to the heightened vigilance across NATO and allied states and materially enabled Russia’s broader political and institutional capture of Georgia.

The erosion of Georgia’s security apparatus thus preceded—and facilitated—the country’s broader authoritarian turn. By the time repression became overt, the institutional safeguards that might have resisted or constrained Russian influence had already been dismantled.

The August 2019 assassination of Zelimkhan Khangoshvili in Berlin provides a stark, empirical illustration of how Georgia’s degraded security environment translated into real‑world Russian operational freedom.

Khangoshvili, a Georgian citizen of Chechen‑Kist origin, had served in the Georgian Army during the 2008 war and later worked in counter‑terrorism structures linked to Georgia’s security cooperation with the United States. According to U.S. intelligence expert Michael Weiss, CIA‑employed individuals were recruited on Khangoshvili’s recommendation due to his reputation and standing. This made him a known figure within Western security circles and a likely target for Russian intelligence.

In May 2015, Khangoshvili survived an assassination attempt in central Tbilisi. The subsequent response by Georgian authorities was conspicuously inadequate. No suspects were identified, CCTV footage was not recovered, and no meaningful investigation followed. Instead of receiving protection, Khangoshvili was denied state security assistance and had his firearms license revoked. He left Georgia shortly thereafter and relocated to Germany.

Four years later, on 23 August 2019, Khangoshvili was shot dead in Berlin’s Tiergarten park, steps away from the Federal Chancellery by a Russian national, Vadim Krasikov. In December 2021, Germany’s Federal Court ruled that the murder was a state‑ordered political assassination carried out on behalf of Russian authorities. The court explicitly cited Khangoshvili’s opposition to the “pro‑Russian government in Georgia” as one of the motives for the killing.

Despite the gravity of the ruling—and the fact that the victim was a Georgian citizen and former security operative—the Georgian government issued no official statement and took no visible follow‑up action. The silence persisted even after the convicted assassin was later exchanged by Russia for a Wall Street Journal journalist detained in Moscow.

The case illustrates two critical dynamics. First, Russian services were able to prepare and attempt an assassination on Georgian soil in 2015 without meaningful interference from Georgian law enforcement or intelligence agencies. Second, once the operation succeeded abroad, Georgia failed to assert even minimal diplomatic or political defense of its own citizen and former security partner.

Taken together, these failures signal early and effective Russian leverage over segments of Georgia’s security apparatus. Moscow demonstrated that Georgian territory and institutions posed no obstacle to Russian intelligence operations, and that cooperation with Western security services offered no protective cover. The message was not only operational but deterrent: those linked to Western cooperation could be targeted without consequence.

For Russia, the strategic gain was clear. The Khangoshvili case confirmed that Georgia had ceased functioning as a hostile or even neutral counterintelligence environment. Russian services could operate with confidence that Georgian institutions would neither disrupt their activities nor impose political costs afterward.

For Georgia, the damage was profound. The state failed to protect one of its own security operatives, abandoned obligations to individuals who worked with Western partners, and forfeited credibility as a sovereign actor capable of defending its citizens. Silence in the face of a court‑confirmed state‑sponsored murder—and again during the subsequent prisoner exchange—underscored a broader reality: by 2019, segments of Georgia’s security system were already compromised.

The August 2019 assassination of Zelimkhan Khangoshvili in Berlin provides a stark, empirical illustration of how Georgia’s degraded security environment translated into real‑world Russian operational freedom.

Khangoshvili, a Georgian citizen of Chechen‑Kist origin, had served in the Georgian Army during the 2008 war and later worked in counter‑terrorism structures linked to Georgia’s security cooperation with the United States. According to U.S. intelligence expert Michael Weiss, CIA‑employed individuals were recruited on Khangoshvili’s recommendation due to his reputation and standing. This made him a known figure within Western security circles and a likely target for Russian intelligence.

In May 2015, Khangoshvili survived an assassination attempt in central Tbilisi. The subsequent response by Georgian authorities was conspicuously inadequate. No suspects were identified, CCTV footage was not recovered, and no meaningful investigation followed. Instead of receiving protection, Khangoshvili was denied state security assistance and had his firearms license revoked. He left Georgia shortly thereafter and relocated to Germany.

Four years later, on 23 August 2019, Khangoshvili was shot dead in Berlin’s Tiergarten park, steps away from the Federal Chancellery by a Russian national, Vadim Krasikov. In December 2021, Germany’s Federal Court ruled that the murder was a state‑ordered political assassination carried out on behalf of Russian authorities. The court explicitly cited Khangoshvili’s opposition to the “pro‑Russian government in Georgia” as one of the motives for the killing.

Despite the gravity of the ruling—and the fact that the victim was a Georgian citizen and former security operative—the Georgian government issued no official statement and took no visible follow‑up action. The silence persisted even after the convicted assassin was later exchanged by Russia for a Wall Street Journal journalist detained in Moscow.

The case illustrates two critical dynamics. First, Russian services were able to prepare and attempt an assassination on Georgian soil in 2015 without meaningful interference from Georgian law enforcement or intelligence agencies. Second, once the operation succeeded abroad, Georgia failed to assert even minimal diplomatic or political defense of its own citizen and former security partner.

Taken together, these failures signal early and effective Russian leverage over segments of Georgia’s security apparatus. Moscow demonstrated that Georgian territory and institutions posed no obstacle to Russian intelligence operations, and that cooperation with Western security services offered no protective cover. The message was not only operational but deterrent: those linked to Western cooperation could be targeted without consequence.

For Russia, the strategic gain was clear. The Khangoshvili case confirmed that Georgia had ceased functioning as a hostile or even neutral counterintelligence environment. Russian services could operate with confidence that Georgian institutions would neither disrupt their activities nor impose political costs afterward.

For Georgia, the damage was profound. The state failed to protect one of its own security operatives, abandoned obligations to individuals who worked with Western partners, and forfeited credibility as a sovereign actor capable of defending its citizens. Silence in the face of a court‑confirmed state‑sponsored murder—and again during the subsequent prisoner exchange—underscored a broader reality: by 2019, segments of Georgia’s security system were already compromised.

Derailing the Anaklia Deep‑Sea Port: Blocking Western Integration in the Black Sea

The cancellation of the Anaklia Deep Sea Port project in January 2020 marked one of the clearest, most consequential decisions through which Georgian Dream government advanced Russian strategic interests without coercion. The project’s termination did not merely halt a commercial investment; it dismantled a core pillar of Georgia’s post‑2008 strategy to anchor itself economically and strategically in the Western‑led order.

From the outset, the Anaklia deep‑sea port was understood—both in Tbilisi and Moscow—as a strategic project, designed as a Western‑backed, deep‑water logistics hub on Georgia’s Black Sea coast, Anaklia would have competed directly with Russia’s Novorossiysk port, strengthened the Middle Corridor, and reduced regional Central Asian and Caucasian dependence on Russia‑controlled transit routes. For Moscow, Anaklia represented a structural threat to its economic and geopolitical leverage in the Black Sea region.

Derailing the Anaklia Deep‑Sea Port: Blocking Western Integration in the Black Sea

The cancellation of the Anaklia Deep Sea Port project in January 2020 marked one of the clearest, most consequential decisions through which Georgian Dream government advanced Russian strategic interests without coercion. The project’s termination did not merely halt a commercial investment; it dismantled a core pillar of Georgia’s post‑2008 strategy to anchor itself economically and strategically in the Western‑led order.

From the outset, the Anaklia deep‑sea port was understood—both in Tbilisi and Moscow—as a strategic project, designed as a Western‑backed, deep‑water logistics hub on Georgia’s Black Sea coast, Anaklia would have competed directly with Russia’s Novorossiysk port, strengthened the Middle Corridor, and reduced regional Central Asian and Caucasian dependence on Russia‑controlled transit routes. For Moscow, Anaklia represented a structural threat to its economic and geopolitical leverage in the Black Sea region.

Russian officials made this assessment explicit. In June 2019, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Grigory Karasin publicly condemned U.S. support for Anaklia, calling Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s earlier endorsement “unacceptable” and framing it as interference in Georgia’s internal affairs. Pompeo, in turn, had warned Georgian leaders that Anaklia would “enhance Georgia’s relationship with free economies and prevent Georgia from falling prey to Russian or Chinese economic influence.” The strategic stakes were clearly understood by all parties.

Despite bipartisan support in the U.S. Congress and backing from the EBRD, the government terminated the investment agreement with the Anaklia Development Consortium in January 2020. Members of Congress from both parties warned that the decision would deter Western investment, weaken Georgia’s sovereignty, and perpetuate dependence on Russian‑controlled infrastructure. These warnings were ignored.

By blocking a Western‑aligned logistics hub, Moscow preserved its dominance in Black Sea maritime trade and prevented Georgia from becoming a key node in alternative East–West supply chains. The decision reversed a decade‑long effort to diversify Georgia away from Russian leverage through connectivity and infrastructure.

The damage was compounded in 2024, when the Georgian government announced the project’s revival under a Chinese‑Georgian consortium. In May 2024, Georgia awarded a 49 percent stake to a consortium led by the state‑owned China Communications Construction Company (CCCC), a firm sanctioned by the U.S. Department of the Treasury since 2021 for its ties to China's military‑industrial complex, and by the U.S. Department of Commerce since 2020 for activities in the South China Sea. Proceeding with a sanctioned Chinese firm reinforced Western concerns that Georgia was abandoning its Euro‑Atlantic orientation in favor of authoritarian‑aligned capital.

The derailment of the Anaklia deep‑sea port amounted to another strategic victory for Moscow in the Black Sea region. A Western‑backed port was blocked; Georgia’s diversification strategy collapsed; and the Black Sea balance shifted further away from Western economic influence. For Georgia, this represented a missed opportunity to transform itself into a secure East–West transit hub and to lock in long‑term Western investment and political commitment.

From Energy Diversification to Dependence: The Kulevi Terminal and Sanctions Evasion

Infrastructure capture extended beyond ports into the energy sector, where Georgia’s dependence on Russia has increased dramatically since 2012. Russian oil imports rocketed from a modest 7 percent of Georgia’s petroleum consumption in 2012 to a whopping 62 percent by 2023, spiking while Russian natural gas imports climbed from near zero to roughly one‑fifth of total consumption. By early 2025, Russian gas imports ($100.6 million) outpaced those from Azerbaijan for the first time in nearly two decades.

At the center of this shift stands the Kulevi oil terminal and refinery on Georgia's Black Sea coast, a gleaming $700 million venture unveiled by Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze in October 2024. In October 2025, RussNeft—tied to sanctioned Russian oligarch Mikhail Gutseriev—delivered the refinery’s first shipment of Siberian crude. Credible reporting suggests that refined products from Kulevi are being rerouted to European markets, raising serious concerns about sanctions circumvention.

Ownership structures further underscore the political dimension. The refinery is owned by Georgian Dream‑linked businesswoman Maka Asatiani; her son, Kakha Zhordania, is a business partner of Sergey Alekseev, the son of GRU deputy chief Lt. Gen. Vladimir Alekseev. These linkages point to the convergence of political power, Russian intelligence networks, and strategic economic assets.

The Kulevi refinery affair seems to be only the tip of the iceberg. Georgia's oil exports increased fifteenfold after 2022, with trade data showing large volumes of ostensibly “Georgian” fuel arriving in EU member states such as Spain. Multiple investigations have suggested that these figures reflect the rebranding and transshipment of Russian‑origin oil. If confirmed, Georgia would be functioning not merely as a consumer of Russian energy, but as an enabling platform for sanctions evasion. Meanwhile, additional evidence has emerged indicating increased Russian activity to use Georgian ports in its efforts to circumvent sanctions and deliver sanctioned oil to consumers abroad through its so‑called shadow fleet. According to one of the most recent investigations, 19 tankers from Russia’s shadow fleet operated through Georgian ports in 2024–2026.

For Russia, the strategic gains are substantial. Georgia offers a processing and transit platform that helps mitigate the impact of Western sanctions at a time of mounting pressure on Russian export routes. The costs for Georgia are severe: loss of hard‑won energy diversification, heightened vulnerability to coercion, erosion of regulatory credibility, and deepening entanglement economic stability with Russian state- and intelligence‑linked economic networks.

Taken together, the Anaklia cancellation and the expansion of Russian‑linked energy infrastructure illustrate a consistent pattern: strategic economic decisions that reduce Western presence while expanding authoritarian leverage. These outcomes were not imposed by force. They resulted from domestic political choices that aligned Georgia’s economic future with Russian—and increasingly Chinese—interests, at the expense of sovereignty and long‑term stability.

Russian officials made this assessment explicit. In June 2019, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Grigory Karasin publicly condemned U.S. support for Anaklia, calling Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s earlier endorsement “unacceptable” and framing it as interference in Georgia’s internal affairs. Pompeo, in turn, had warned Georgian leaders that Anaklia would “enhance Georgia’s relationship with free economies and prevent Georgia from falling prey to Russian or Chinese economic influence.” The strategic stakes were clearly understood by all parties.

Despite bipartisan support in the U.S. Congress and backing from the EBRD, the government terminated the investment agreement with the Anaklia Development Consortium in January 2020. Members of Congress from both parties warned that the decision would deter Western investment, weaken Georgia’s sovereignty, and perpetuate dependence on Russian‑controlled infrastructure. These warnings were ignored.

By blocking a Western‑aligned logistics hub, Moscow preserved its dominance in Black Sea maritime trade and prevented Georgia from becoming a key node in alternative East–West supply chains. The decision reversed a decade‑long effort to diversify Georgia away from Russian leverage through connectivity and infrastructure.

The damage was compounded in 2024, when the Georgian government announced the project’s revival under a Chinese‑Georgian consortium. In May 2024, Georgia awarded a 49 percent stake to a consortium led by the state‑owned China Communications Construction Company (CCCC), a firm sanctioned by the U.S. Department of the Treasury since 2021 for its ties to China's military‑industrial complex, and by the U.S. Department of Commerce since 2020 for activities in the South China Sea. Proceeding with a sanctioned Chinese firm reinforced Western concerns that Georgia was abandoning its Euro‑Atlantic orientation in favor of authoritarian‑aligned capital.

The derailment of the Anaklia deep‑sea port amounted to another strategic victory for Moscow in the Black Sea region. A Western‑backed port was blocked; Georgia’s diversification strategy collapsed; and the Black Sea balance shifted further away from Western economic influence. For Georgia, this represented a missed opportunity to transform itself into a secure East–West transit hub and to lock in long‑term Western investment and political commitment.

From Energy Diversification to Dependence: The Kulevi Terminal and Sanctions Evasion

Infrastructure capture extended beyond ports into the energy sector, where Georgia’s dependence on Russia has increased dramatically since 2012. Russian oil imports rocketed from a modest 7 percent of Georgia’s petroleum consumption in 2012 to a whopping 62 percent by 2023, spiking while Russian natural gas imports climbed from near zero to roughly one‑fifth of total consumption. By early 2025, Russian gas imports ($100.6 million) outpaced those from Azerbaijan for the first time in nearly two decades.

At the center of this shift stands the Kulevi oil terminal and refinery on Georgia's Black Sea coast, a gleaming $700 million venture unveiled by Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze in October 2024. In October 2025, RussNeft—tied to sanctioned Russian oligarch Mikhail Gutseriev—delivered the refinery’s first shipment of Siberian crude. Credible reporting suggests that refined products from Kulevi are being rerouted to European markets, raising serious concerns about sanctions circumvention.

Ownership structures further underscore the political dimension. The refinery is owned by Georgian Dream‑linked businesswoman Maka Asatiani; her son, Kakha Zhordania, is a business partner of Sergey Alekseev, the son of GRU deputy chief Lt. Gen. Vladimir Alekseev. These linkages point to the convergence of political power, Russian intelligence networks, and strategic economic assets.

The Kulevi refinery affair seems to be only the tip of the iceberg. Georgia's oil exports increased fifteenfold after 2022, with trade data showing large volumes of ostensibly “Georgian” fuel arriving in EU member states such as Spain. Multiple investigations have suggested that these figures reflect the rebranding and transshipment of Russian‑origin oil. If confirmed, Georgia would be functioning not merely as a consumer of Russian energy, but as an enabling platform for sanctions evasion. Meanwhile, additional evidence has emerged indicating increased Russian activity to use Georgian ports in its efforts to circumvent sanctions and deliver sanctioned oil to consumers abroad through its so‑called shadow fleet. According to one of the most recent investigations, 19 tankers from Russia’s shadow fleet operated through Georgian ports in 2024–2026.

For Russia, the strategic gains are substantial. Georgia offers a processing and transit platform that helps mitigate the impact of Western sanctions at a time of mounting pressure on Russian export routes. The costs for Georgia are severe: loss of hard‑won energy diversification, heightened vulnerability to coercion, erosion of regulatory credibility, and deepening entanglement economic stability with Russian state- and intelligence‑linked economic networks.

Taken together, the Anaklia cancellation and the expansion of Russian‑linked energy infrastructure illustrate a consistent pattern: strategic economic decisions that reduce Western presence while expanding authoritarian leverage. These outcomes were not imposed by force. They resulted from domestic political choices that aligned Georgia’s economic future with Russian—and increasingly Chinese—interests, at the expense of sovereignty and long‑term stability.

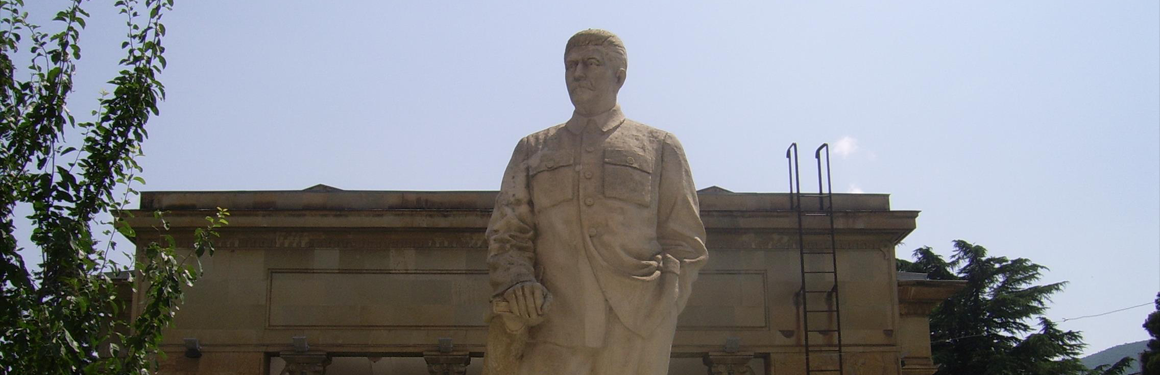

Weaponizing History: The Rehabilitation of Stalin as an Instrument of Influence

One of the most under‑examined yet strategically consequential dimensions of Georgia’s drift has been the systematic manipulation of historical memory and identity. Russian influence operations and their domestic enablers have exploited Georgia’s Soviet legacy to soften resistance to authoritarianism and reframe repression as continuity rather than rupture.

Since Georgian Dream came to power in 2012, at least twelve new monuments to Joseph Stalin have been erected across Georgia, often with the acquiescence—or active support—of local authorities.

Polling data underscore the impact of this campaign. According to a 2022 survey carried out by the Coalition for Information Integrity, 46 percent of Georgians agreed that a “patriotic Georgian should be proud of Stalin.” Russian propaganda and its allies have thus succeeded at selling Stalin as a patriotic symbol of Georgian national pride, appealing to his Georgian descent. Such narratives are disseminated through various channels, including social media platforms such as TikTok, where pro‑Stalin content has gained traction among Georgian youth.

This reframing aligns closely with the Kremlin’s broader information strategy across the post‑Soviet space: replacing democratic narratives of rupture with authoritarian narratives of continuity, order, and inevitability. By recasting Stalin as a patriotic figure, Russian propaganda undermines one of the most powerful moral barriers to authoritarian consolidation: historical accountability for Soviet crimes.

Weaponizing History: The Rehabilitation of Stalin as an Instrument of Influence

One of the most under‑examined yet strategically consequential dimensions of Georgia’s drift has been the systematic manipulation of historical memory and identity. Russian influence operations and their domestic enablers have exploited Georgia’s Soviet legacy to soften resistance to authoritarianism and reframe repression as continuity rather than rupture.

Since Georgian Dream came to power in 2012, at least twelve new monuments to Joseph Stalin have been erected across Georgia, often with the acquiescence—or active support—of local authorities.

Polling data underscore the impact of this campaign. According to a 2022 survey carried out by the Coalition for Information Integrity, 46 percent of Georgians agreed that a “patriotic Georgian should be proud of Stalin.” Russian propaganda and its allies have thus succeeded at selling Stalin as a patriotic symbol of Georgian national pride, appealing to his Georgian descent. Such narratives are disseminated through various channels, including social media platforms such as TikTok, where pro‑Stalin content has gained traction among Georgian youth.

This reframing aligns closely with the Kremlin’s broader information strategy across the post‑Soviet space: replacing democratic narratives of rupture with authoritarian narratives of continuity, order, and inevitability. By recasting Stalin as a patriotic figure, Russian propaganda undermines one of the most powerful moral barriers to authoritarian consolidation: historical accountability for Soviet crimes.

Religion as a Vector: Fusing Totalitarian Memory with Moral Legitimacy

A key accelerator of this process has been the integration of Stalinist imagery into religious narratives. Russian and pro‑Russian actors have increasingly promoted the false notion that Stalin was a “secret believer” or protector of the Orthodox Church, thereby fusing authoritarian memory with moral legitimacy.

This strategy became visible in early 2024 at Tbilisi’s Holy Trinity Cathedral, Georgia’s most important religious site, where an icon depicting Saint Matrona of Moscow was found to include Stalin’s image. The discovery triggered public outrage and debate over the propriety of venerating a figure responsible for mass repression.

Strategic Function: Memory as an Enabler of Repression

What may appear as symbolic politics serves a concrete strategic function. The partial rehabilitation of Stalin in Georgia has helped soften societal resistance to state violence, normalize the moral logic of repression, and reframe dissent as destabilization. Stalin functions as a “propaganda gateway”—an emotionally resonant figure through which broader narratives hostile to liberal democracy, Western integration, and pluralism are introduced into mainstream discourse.

For Russia, the benefit is clear. Distorted historical memory weakens democratic immunity, reduces resistance to authoritarian governance, and erodes Georgia’s ideological alignment with Europe. For the Georgian Dream regime, these narratives provide ideological cover for coercive policies by embedding them within a broader story of order, tradition, and sovereignty.