The Transition Project: Post‑Soviet Experience and Russia’s Recent Track Record

We see that Russia has slid towards authoritarianism. Does this mean that the democratic experiment of the 1990s was an absolute failure?

By Vladimir Milov May 29, 2024

We see that Russia has slid towards authoritarianism. Does this mean that the democratic experiment of the 1990s was an absolute failure?

By Vladimir Milov May 29, 2024

What went wrong, could it have been worse, and what lessons can we learn from the reforms of the 1990s? We continue to publish chapters of The Transition Project, a step‑by-step expert guide to democratic transformations in Russia after the change of power.

Any reforms and attempts at democratic transformation should be based on a thorough analysis of lessons learned and correction of past mistakes. We have a vast amount of material to study that the reformers of the 1990s did not have. Over the past two decades, there has been an animated intellectual discussion in Russia about the shortcomings and mistakes of previous democratic transformations and what is needed to prevent a regression to authoritarianism if Russia is to have a chance for a new democratic experiment.

We see that the country has slid towards authoritarianism. Does this mean that the democratic experiment of the 1990s was an absolute failure?

Despite very difficult conditions (centralized Soviet economy, consistently low oil prices), Russia managed to complete the decade of reforms with economic growth. It started in 1999 and ended in 2008 with average GDP growth of 7% per year and average real disposable income growth of more than 12% per year. The transition to a market economy happened: according to the EBRD, the private sector’s share of Russian GDP reached 70% by the end of the 1990s. When Putin began to restrict private initiative in the economy and pluralism in the political system, growth effectively stopped.

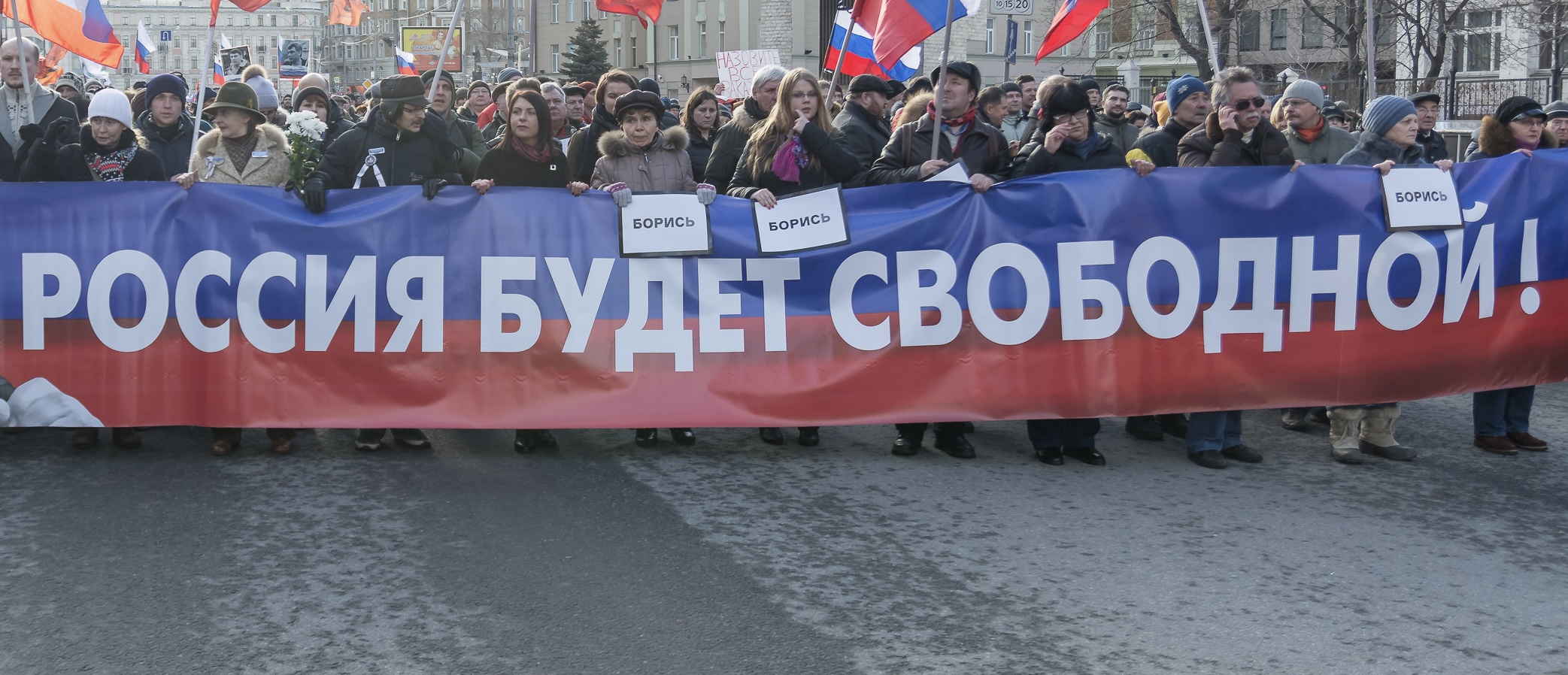

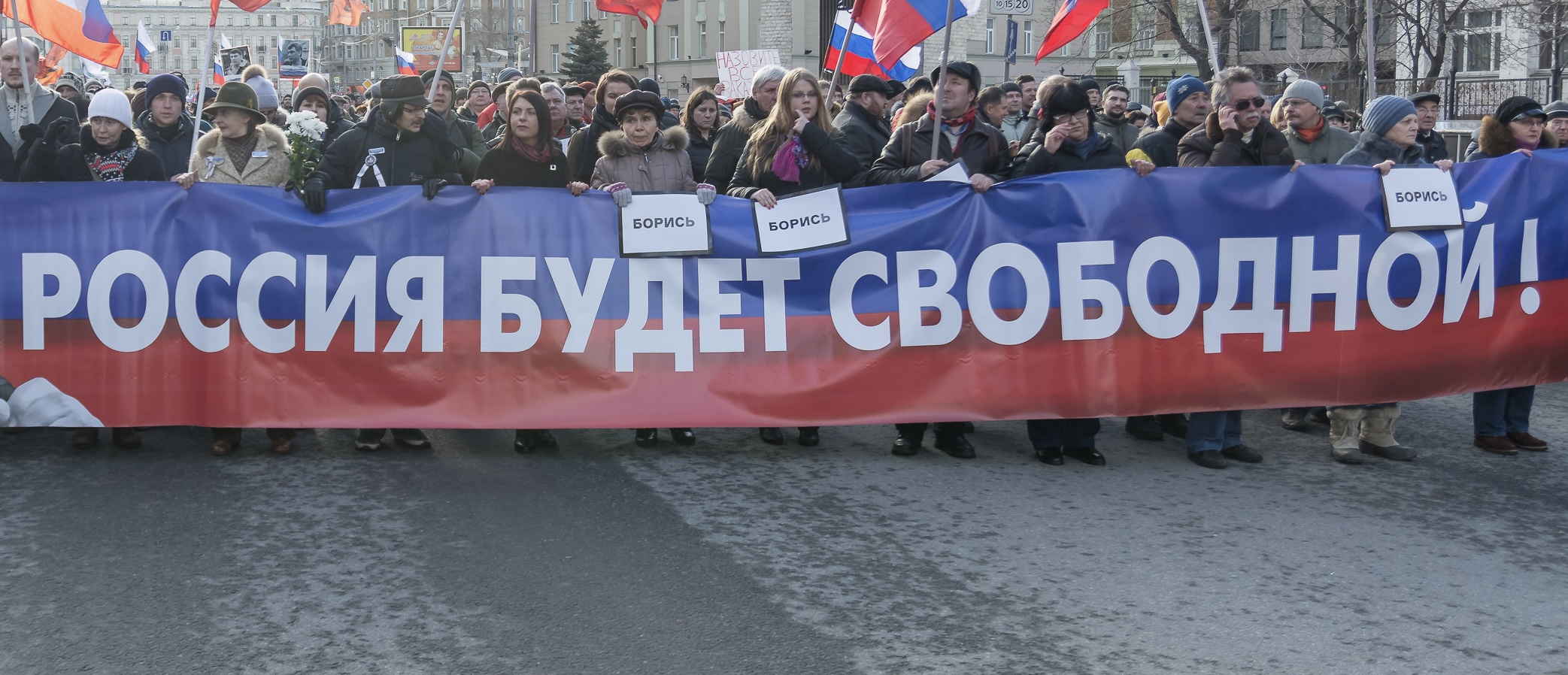

In the 1990s, Russia succeeded in creating a space of freedom and a prototype of democratic institutions that would have a huge impact on its future development. Parliamentary elections in December 1999 were recognized by the international community as free and fair and resulted in a highly competitive parliament of 9 factions, which was able to pass key reform packages that ensured economic growth in the 2000s. Until 2005, Russia was ranked «partly free» in Freedom House’s index of democracies. The experience of more than a decade of political pluralism, freedom of the press, assembly, religion, and political competition will have a profound impact on the thinking of generations to come. The political resistance of the last decade, the mass protests of 2012–2021, the emergence of popular political leaders and intellectuals (Alexei Navalny, Yevgeny Roizman, Ilya Yashin, etc.) are the result of the 1990s.

Russians were never happy about corruption or weakness of the law, they were against the war in Chechnya — Boris Nemtsov, then governor of Nizhny Novgorod, collected a million signatures against the war in 10 days and brought the folders to the Kremlin. Unfortunately, no real mechanisms of public influence on the situation in the country were formed. This allowed Vladimir Putin to gradually seize power, imitating democratic institutions along the way. In 2004, he canceled gubernatorial elections, using the Beslan terrorist attack as a pretext. He changed in his favor the system of elections to the upper house of parliament (the Federation Council), the system of appointing judges, established control over key TV channels, newspapers, corporations, manipulated the results of the 2003 parliamentary elections to ensure a «constitutional» supermajority (more than two‑thirds of seats) in the State Duma for the ruling United Russia party. All this time he aimed to convince the public that Russia was a democratic state. And people believed. The «Great Awakening» began only in 2011 with the protests on Bolotnaya Square and Sakharov Avenue, but it was too late, the nascent democratic institutions had been dismantled.

Many Russians did not notice the onset of dictatorship. But they cannot be accused of deliberately abandoning the gains of the democratic reforms of the 1990s. The electoral behavior of citizens, public opinion polls, and Putin’s willingness to maintain a pseudo‑democratic facade for decades testify to this: there was a demand in Russian society for order and a quiet life, but there was no demand for authoritarianism.

Russia’s independence in 1991 was the result of rapid and rather chaotic changes that were in no way institutionally prepared. No one had planned in advance for the development of a democratic political system: the plans of a group of economists, many of whom later took reformist positions in the government, were only concerned with the transition to a market economy. Much less attention was paid to political reforms.

Economic reforms were indeed needed: even in the relatively benign 1970s, the standard of living of the Russian population was quite low, with Leonid Brezhnev, General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, publicly acknowledging «a shortage of food for the population.“ By the late 1980s there were widespread shortages of food and essential goods. Political change was seen as a bonus: the implication was that once a free market economy was introduced, living standards would rise and functioning institutions would begin to emerge (as if by themselves).

As a result, the chaotic state of Russian political institutions in the early years of reforms led to the constitutional crisis of 1992–1993 (culminating in the October 1993 clashes in Moscow) and widespread disillusionment with the reforms among Russian society, whose standard of living plummeted. Several important issues have been left out of the picture:

In a chaotic institutional environment with a Constitution written in a completely different country a decade and a half ago, with no elections, no political parties, etc., the political environment quickly degenerated to a rivalry of personal interests and political groups. Political discourse quickly polarized into camps of supporters and opponents of reforms, and the institutional environment receded into the background. Many reformist politicians sincerely believed that the main thing was to keep them in power and prevent anti‑reformists from gaining power.

Had it been possible to call a Constituent Assembly and new elections in the fall of 1991, during a brief period of political consensus when Yeltsin’s proposals for economic reform and additional powers were supported by more than 90% of the votes at the Congress of People’s Deputies, the process might have gone more smoothly. Russia would have had a new constitution, a new parliament, and a new configuration of political parties — something that did not materialize in 1991–1993.

But the realities were such that without rapid economic reforms, the country was in danger of real famine and destabilization (the Soviet economic system had completely collapsed by the end of 1991, market mechanisms were not working, and food and basic consumer goods were disappearing from stores). This explains the excessive focus on the economy to the detriment of political institutions.

Another important factor worth mentioning is that many political mistakes were made back in the 1980s. Had Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev embarked more decisively on the path of economic and political reform, rather than resisting it until the last moment with the conservatives around him who later led a revanchist putsch in August 1991, the transition would have been much smoother and would not have taken the form of crisis management when the country was on the verge of starvation.

Thus, the situation quickly turned into a feud between the pro‑presidential camp and the anti‑Yeltsin opposition. The anti‑Yeltsin camp is often portrayed as more democratic because it represented parliament rather than a semi‑authoritarian strongman president with extraordinary powers, but in reality it leaned just as much toward the semi‑authoritarian rule of Supreme Soviet Chairman Ruslan Khasbulatov and his inner circle. The constitutional crisis of 1992–1993 was not a struggle of democrats against an authoritarian president (although some anti‑Yeltsin forces sincerely believed it was) — it was a struggle for total control of the country between two personalist camps with little interest in building democratic institutions.

The result of the «winner‑takes-all» competition was the adoption of a super‑presidential Constitution in 1993. The Constitution of the Russian Federation was not undemocratic, but it had many design flaws and ambiguities — for example, there was no clarity on the appointment/election of the upper house of parliament or regional governors — and gave the president more room for maneuver than any other political institution, making him the de facto arbiter of all ambiguous issues. The Constitution was adopted without detailed discussion: amid a political crisis, Boris Yeltsin hastily convened a constitutional meeting on June 5, 1993, consisting mainly of his supporters, and the Constitution was adopted in a referendum on December 12, 1993. The draft Constitution was published only a month before the vote. This did not support either the quality of the new Constitution or its credibility. And Yeltsin’s focus on winning the political struggle against his personal opponents subsequently led to Putin’s seizure of power and re‑autocratization.

The constitutional crisis of 1992–1993 could have been avoided (or at least minimized) if the construction of political institutions had started immediately after the collapse of the USSR in 1991, instead of being postponed to the future. The crisis culminated in the tragic clashes in Moscow in October 1993, initiated mass disillusionment with Yeltsin and the reforms, and led to demands for «order» and a «strong hand» at the very end of the 1990s (and then to longing for former supposed greatness and dangerous resentment). Putin, an energetic officer, was able to use this demand for his subsequent seizure of power.

Because of the closed decision‑making system in Yeltsin’s inner circle, such phenomena as «loans in exchange for shares» emerged, and an oligarchy was born. In a more balanced institutional environment, this would have been significantly more difficult. Many reformers who would have been very useful throughout the 1990s and beyond found themselves discredited and politically buried after joining Yeltsin’s camp, which sank with the disgraced president.

Due to the lack of development of political parties in 1991–1993, Russian politicians lacked incentives to work directly with the population and develop skills to promote political ideas and persuade people through campaigning. Most focused on trying to achieve their goals in the corridors of power. Ordinary voters could not properly participate in building democratic institutions.

Note that the early parliamentarism of 1990–1993 in Russia (and onwards from 1994) was not an example to be replicated. Parliament fiercely rejected demands to reform itself from the outdated Soviet system of a Congress of Deputies and a rotating Supreme Soviet into a professional, permanently sitting parliament. Even when in April 1993 67% of Russians voted to dissolve the Russian parliament, the Congress of Deputies flatly refused to dissolve itself (even though its term was coming to an end). This self‑dissolution would have helped avoid the October 1993 confrontation: President Yeltsin favored early presidential and parliamentary elections as a universal solution to the crisis. As a result of the mass exodus of pro‑reform deputies to work in Yeltsin’s administration, the parliament turned dangerously toward the counter‑reform majority and made obstructionism against Yeltsin its main objective, which did not reflect public opinion at the time.

As a result, the authority of parliament as an institution fell to an incredibly low level in the first years of reforms. The State Duma has not been able to regain it: since 1993, it too has been dominated by communists and other anti‑Yeltsin opposition groups, and has developed a similar obstructionist and revisionist image. The idea of parliamentarism has not spread widely in Russia — and this is not only Yeltsin’s or Putin’s fault. Special institutional measures need to be taken to make parliament a functioning democratic institution that is not prone to chaos and capture by revisionist forces. Examples of such parliamentary capture in the post‑communist era are widely known — from Viktor Orban’s Hungary to Aleksandar Vucic’s Serbia, Ukraine under Viktor Yanukovych or Moldova under Vladimir Voronin, etc.

Another important institutional weakness of the 1990s was the failure to address regional self‑governance issues. The Yeltsin administration was unwilling to grant significant powers to the regions; disputes over whether governors should be directly elected by the population or centrally appointed continued until 1996, when a special decision of the Constitutional Court established that governors should be elected. However, Yeltsin’s 1993 Constitution did not explicitly state that Russian regional governors should be directly elected by the population, which allowed Putin to later abolish gubernatorial elections.

And the 1993 Constitution failed to properly spell out these issues. The emphasis in Articles 71–72 is on compiling a list of issues of exclusive jurisdiction of the federal government and joint federal‑regional jurisdiction, while Article 73 contains an empty formula «everything not specified above remains under the jurisdiction of the regions.” The powers of the regions are not defined, leaving room for the subsequent redistribution of power in favor of the federal center. The Constitution did not define an independent financial base for the regions, the taxes from which form the exclusive source of regional revenues, which allowed Putin to redistribute taxes in favor of the federal center in 2004 (before the counter‑reform, the distribution of tax revenues between the center and the regions was about 50/50, whereas afterwards the federal center received about 65% of all revenues from consolidated tax revenues, leaving the regions only 35%). The lack of an independent revenue base undermined the political autonomy of the regions and the very foundations of federalism. The dependence of governors on federal subsidies to finance vital regional expenditures made them more politically loyal.

Another issue that should have been spelled out in the Constitution is the basic design of the system of power in the regions, guaranteeing the necessary checks and balances that counterbalance the coercive power of the regional government in the same way that the corresponding checks should counterbalance the power at the federal level. In the years that followed, regional governors widely abused their powers throughout Russia, voluntarily changing the way regional legislatures are elected and operate, etc.

Local self‑government in Russia de facto never appeared after 1991. The powers and financial basis of local self‑government were extremely limited and primitive; the 1993 Constitution only declaratively proclaimed local self‑government without providing real mechanisms to guarantee its sustainability and influence. Direct elections of mayors and district heads were completely abolished by Putin and the regions in the 2000s. Local authorities' own tax revenues have never exceeded 5% of the total consolidated budget of Russia. In 1998, Russia introduced a local sales tax (maximum 5%) to create an independent tax base for the districts. However, local authorities had to fight with the regions to ensure that this money actually went to local budgets, and the Constitutional Court twice ruled the local sales tax unconstitutional. Since 2004, this tax has been abolished, leaving local authorities with crumbs from the table of general revenues of the consolidated budget.

The design flaws concerning regional autonomy and local self‑governance are understandable. Since the early 1990s, the uncertain status of the Russian regions and their constant attempts to pursue their own protectionist policies and obstruct federal reforms forced Yeltsin’s camp of reformers to seek to minimize regional autonomy in order to ensure the implementation of the market reform program. Political and public awareness of the importance of local self‑government was and remains low — people do not understand why another level of government other than federal and regional is needed. Numerous high‑profile cases of abuse of local power in cities, towns and districts by inadequate populists or outright criminals were used by the central government as a justification for eliminating the autonomy of local self‑government. Both federal and regional authorities considered local self‑government as an undesirable competitor in the struggle for control and jointly suppressed its emergence.

However, where local self‑government has been able to emerge and sustain itself, it has served as an important guarantor of political competition, a certain degree of media freedom and transparency of governance, as well as a necessary element of the system of political checks and balances. As an example, the intense political competition between regional governors and popularly elected mayors of regional capitals helped to maintain a significant degree of press freedom and political competition in many regions until the 2000s.

Another systemic failure of institution‑building in the 1990s was the inability to establish a functioning independent judiciary. The 1993 Constitution immediately established that judges were to be appointed by the president (Article 128), which effectively blocked the possibility of genuine judicial independence. A study by the publication Project showed that in 1995–2000 70–75% of candidates for the position of judge were closely connected with the administrative and law enforcement apparatus — their professional biography included either administrative or law enforcement agencies — and only 20–25% of candidates were selected from the bar or the corporate sector. In the Putin era, the balance has shifted even further.

Let us summarize:

A lot of things could have gone much worse in the 1990s.

First, Russia avoided an all‑out war against or between regions or a war against former Soviet republics aimed at restoring the USSR, following the scenario of Yugoslavia under Slobodan Milosevic. In the early 1990s, many regions considered independence, but these aspirations were resolved through negotiations and the peaceful conclusion of the Federal Treaty in 1992. (However, the bloody example of the suppression of the Chechen attempt to secede shows that although Yeltsin had invited the regions to «take as much sovereignty as they could swallow», he clearly did not have in mind the possibility of their real self‑determination.)

The 1993 anti‑Yeltsin coup was led by conservatives and revanchists who tried to restore the USSR by force. In March 1996, the State Duma, where communists and nationalists held a majority of seats, passed a resolution calling for the denunciation of the 1991 Belovezh Agreement on the dissolution of the USSR (effectively opening the way for actions aimed at restoring the Soviet Union by force). That these attempts failed can be explained by Yeltsin’s ability to maintain the loyalty of the las enforcement and intelligence agencies, as well as by the pluralistic political environment of that era. Later, under Putin’s authoritarian system, revisionist policies succeeded.

Economic reforms could have been much less successful. Economic growth began as early as 1997, and from 1999 came a decade of economic boom with an average annual GDP growth of 7 percent. The private sector’s share of GDP grew. The pluralistic environment of the 1990s and the absence of an etatist grip on business played an important role here. As the 1994–1996 period of indecision showed, stalled reforms can significantly delay growth, while intensified reforms (as happened after 1997) can accelerate it. Without pluralism, relative relaxation of rules for business, and serious reforms, Russia could easily stagnate for decades.

The chances of a successful democratic transition next time will be higher for the following reasons:

There are some important lessons to be learned from the experience of the post‑Soviet transition:

The time horizon for implementing democratic reforms will be relatively short (we look at time factors in Chapter 9), and the results that must be achieved in this short period will be significant or there will be a backlash. Therefore, careful pre‑planning and rapid action to build major institutions is required. Within a few years, Russia should become a decentralized, open country with checks and balances in place that can cope with attempts to dismantle democratic institutions or revive imperialist revanchism.

The focus in building democratic institutions for transition should be on creating a system that prevents a resurgence of Putin‑like rule by force and on building an inclusive political system whose form is shaped by a wide range of diverse actors across the country rather than a limited number of players tied to the federal government. As the experience of the 1990s shows, although pro‑imperialist and etatist forces may be strong, a diverse, albeit imperfect, system of institutions can help to prevent the country from sliding toward authoritarianism and aggressive imperialism. On the other hand, the institutional weaknesses of the state system of the 1990s described above (too much emphasis on the power of the president as a «guarantor» of reforms with weaknesses in other institutions) allowed the fragile democracy to collapse and the authoritarian rule of the siloviki to be established.

The key measures on which there is consensus among various political forces, not only in the liberal part of the political spectrum, are as follows:

Some of the key measures of this kind will be discussed in this report; there may be others that should be the subject of careful public debate.

The unsuccessful parliamentary experiment of the 1990s and early 2000s was a factor in the failure of democratic reforms. The promotion of Russian parliamentarism should become the central focus of building new democratic institutions. How to make the new parliament successful?

Parliament should be given real powers to form the executive branch of government. In the 1990s and 2000s, these powers were mostly advisory or limited to veto power on some important issues (e.g., appointing the head of government). Instead, parliament must determine the composition of government through parliamentary coalition agreements. The process of negotiating and concluding such coalition agreements as a result of free and fair elections should be detailed in the law.

The primacy of parliamentarism should be transferred to regional and local levels. Since the early 1990s, regional and local parliaments and legislative councils have rapidly degenerated into an annex to the executive, contributing to the decline of parliamentarism at the national level. Regional and local legislatures should be given decisive powers in the formation of the executive and related oversight. This should limit the powers of the executive at the regional and local levels to the same extent as at the federal level.

Permanent institutionalized oversight by parliamentary bodies at various levels throughout the country (federal, regional, local) over the executive branch should become the basis of the new system of power and the new norm of the Russian democratic system and insurance against usurpation of power by the executive branch. But it is also necessary to create mechanisms to protect against potential seizure of power by the parliament; we have seen this in some transition countries (including even EU member states such as Hungary).

Giving real powers to parliamentary bodies and the coalition system will also stimulate the development of functioning representative political parties, something that was not achieved in the experiment of the 1990s.

The failure to create strong regional autonomy and strong, empowered local self‑governance were key failures of the democratic experiment of the 1990s. Promoting regional autonomy and local self‑governance is a key element of our vision of a new, decentralized Russia where citizens actively participate in democratic governance and institutional checks and balances protect Russian democracy from backsliding. These issues are discussed in more detail in Chapter 5 of our report.

The new system should create guarantees for an ecosystem of independent political parties to thrive. The transition to a parliamentary system of government at the federal, regional and local levels will give parties a boost and encourage them to actively engage with grassroots voters — ordinary members of Russian society — to secure their positions of power.

Today, it is actively discussed that the opportunity was missed in the early 1990s to carry out lustration and close the way for former Soviet intelligence officers to enter the civilian government of the new Russia. The fact that former KGB officers, including Putin and his entourage, infiltrated the system of government contributed greatly to the demise of democracy: the intelligence officers in the Soviet Union were trained to disregard human rights and dignity.

The authors of the report believe that lustration should be an integral part of the new democratic construction in Russia. The new government must be civic‑minded and free of authoritarian and hate‑mongering biases. Although lustration is not a panacea, as many people think, it can help create a new civil society‑oriented system of government. The experience of Central and Eastern Europe in conducting post‑communist lustration should be analyzed in detail and competently applied in Russian conditions.

Resentment, the longing for a huge strong state that everyone fears, brought terrible consequences: wars in Chechnya, Georgia, Moldova, Syria, finally in Ukraine. The new political order has been purged of any potential influence of the aggressive imperialist school of thought and of any means that might allow Russia to wage wars of aggression in the future. Such arrangements should take into account the experience of democratic state‑building in Germany and Japan after 1945.The new basic legal framework should include:

As the experience of the 1990s and 2000s shows, media bias can be a significant negative factor contributing to citizens' disillusionment with democracy and creating favorable conditions for propaganda, the takeover of private media and, ultimately, for an authoritarian seizure of power. Special mechanisms are needed to protect the media from takeover or undue influence by the state or private players (oligarchs). Alexei Navalny’s presidential program for 2018 proposed such mechanisms; these issues are also addressed in our report.

The Russian system of governance, as well as the legislative system that emerged after 1991, were oriented mainly to the powers of the state and paid only limited and declarative attention to the protection of human rights and dignity. They are seen as secondary to the powers of the state necessary to ensure «order», «security», etc. In the Criminal Code and the Code of Administrative Offenses of the Russian Federation there is a huge bias: ordinary citizens are punished for the smallest crimes, while such significant crimes as abuse of power by state officials remain unpunished or are punished insignificantly. Part 3 of Article 55 of the 1993 Constitution of the Russian Federation opens the way for the authorities to any abuse of civil rights: it allows them to legislatively curtail the constitutional rights of Russian citizens «in order to protect the foundations of the constitutional order, morality, health, rights and legitimate interests of other persons, to ensure the defense of the country and security of the state." This provision has been widely used by Putin since 2000 to introduce and pass laws aimed at limiting the powers of citizens and expanding the powers of the state.

What should be done to reconstruct rights and freedoms?

By Olga Khvostunova

May 29, 2024

Report

Report Under what circumstances could the collapse of Putin’s regime occur, what will replace it?

By Vasiliy Zharkov

By Nikolay Petrov

May 29, 2024

Report

Report We may not have direct insight into the thoughts and intentions of Russian elites. However, we can speculate on the areas they need to consider for embracing change

By Vasiliy Zharkov

March 14, 2024

What should be done to reconstruct rights and freedoms?

By Olga Khvostunova

May 29, 2024

Report

Report Under what circumstances could the collapse of Putin’s regime occur, what will replace it?

By Vasiliy Zharkov

By Nikolay Petrov

May 29, 2024

Report

Report We may not have direct insight into the thoughts and intentions of Russian elites. However, we can speculate on the areas they need to consider for embracing change

By Vasiliy Zharkov

March 14, 2024