The Transition Project: The Importance of Timing

How to avoid making new mistakes

By Vasily Gatov May 29, 2024

How to avoid making new mistakes

By Vasily Gatov May 29, 2024

When, sooner or later, events occur that could restart the process of democratic transit in Russia, potential future reformers will inevitably be faced with the question “where to start?” and one can only hope that it will be accompanied by the question “how to avoid making new mistakes?”. What will be the sequence of steps in both cases, and what are the universal stages of any transit? We continue to publish chapters of The Transition Project, a step‑by-step expert guide to democratic transformations in Russia after the change of power.

The lessons of the first transit are analyzed in Chapters 1 and 3, and this analysis is aimed at helping the next generation of politicians to avoid repeating the mistakes already made; however, it is also necessary to anticipate new problems, and to have ideas and tools ready to solve them.

Putin’s death or any other removal from power does not mean that the new Kremlin authorities will decide the morning after to repeal all his laws, release political prisoners, welcome back those in exile, and call free elections. On the contrary, it is much more likely that immediately after Putin’s departure the regime will need a forceful reinforcement and tightening of domestic politics, since Putin’s successor will need — even with the best future intentions — to first consolidate his own power and ensure its survival and stability. We proceed from the assumption that Putin’s “sudden” successor will not be interested in continuing the war in Ukraine — but we do not rule out the possibility that the continuation of the war may be the only tool to achieve consensus in the ruling elite. Also, the current economic situation in Russia is not acutely crisis‑ridden, but the possibility of a sharp escalation of socio‑economic tensions cannot be ruled out, which will certainly shape the available policy options.

The long “autumn of the patriarch”, continuing as another presidential term of Vladimir Putin (who will turn 78 at the end of this period, exactly as Stalin did in 1953), will no doubt complicate any attempt to return the Russian Federation as a whole to the path of democratic transit.

In the scenario of a rapid (within a year) change of power it makes sense to talk about the sequence of actions within the framework of a unified Russian state, in which case it will be necessary to restore normal federal relations. In the second scenario, the central issue is likely to be that of moderating the disintegrating imperial state, parts of which will seek to separate from it at all costs, while chauvinistic and xenophobic sentiments are simultaneously growing.

As it seems to us, any periodization and definition of the sequence of actions in the event that Russia starts moving towards a new period of democratic transit must proceed from the fact that such a movement will have 4 (5 at most) stages:

The stage of long‑term preparation, which has been underway for several years, including through the efforts of such projects as Reforum, Re:Russia and some others. At the same time, it is necessary to conduct political work, both in exile and inside Russia, to build consensus around the general direction of reforms, and to create potential framework coalitions and alliances that can be activated as soon as the situation allows.

The stage of power jockeying in a moment of crisis; no matter how Vladimir Putin’s personal regime ends, it is unlikely that his potential successors will have elaborate plans for what should be done after his departure. The readiness of the successor regime to dismantle Putin’s repressive legacy will open up limited opportunities to offer him reasonable plans and roadmaps thought out in the previous period. The existence of proto‑unions of political forces that, on the one hand, represent significant groups of the population and, on the other hand, have a more ready and perfect agenda for future changes, will allow the liberal group to increase its weight in the future inevitable roundtable.

The stage of the “round table” occurs when various political forces negotiate the rules for a return to a civil, electoral, representative democratic regime. The reasons why an authoritarian power agrees to the “round table” format are usually related to mass discontent and economic and social crises, which cannot be suppressed with brute force. The experience of Spain and Poland in the 1980s is particularly relevant for a future Russia, since in both cases the democratization of fairly rigid authoritarian regimes took place (in the case of Poland, with the presence of Soviet troops). This format, especially in a situation where a weakening authoritarian power agrees to negotiations under pressure, is characterized by the gradual “migration” of legitimacy and actual power from the dictator (or party) into the hands of institutions, the creation of which is agreed upon within the framework of the “round table.“ It is likely (albeit not necessary) that during this period, the final dismantling of the quasi‑institutions created by the Putin regime will take place, along with the formation of new ones, possibly based on the principles proposed by liberals. It is important to note that the “round table” format typically emerges as a gesture of goodwill from the hegemon (or the authorities), whether compelled or voluntary. Generally, this approach serves as a means to avoid revolutionary violence as a method of regime change and to offer specific guarantees to representatives of authoritarian or totalitarian power after free elections.

The “new parliament” stage, when all or part of the mutually agreed proposals will be introduced in the legislature and enacted into law, with liberal factions able to push for the interests of their constituents and the democratic order of the country as a whole.

The stage of a government of national confidence, when, as a result of elections, all or a majority of political forces will find it possible to agree for a certain period to a broad coalition government, with cooperation both in parliament and local governments, so as to “heal” society and the country from the wounds and pathologies inflicted by the Putin regime. Such an agreement would be an ideal format for putting Russia back on the path of democratic transit.

Despite the significant differences between the circumstances that will accompany the new launch of the democratic transition “earlier” and “much later,” there are common fundamental problems in both cases. For example, in the first scenario, it is quite likely that, in order to consolidate power and eliminate political unrest, the potential successor to Putin will have to impose martial law, completely abolishing civil liberties. Despite the radical anti‑democratic nature of such measures, they may be beneficial for getting rid of some individuals and institutions (quasi‑institutions) that emerged under Putin. However, the range of political forces that the interim regime deems acceptable to discuss the future with may also be reduced. On the contrary, in the second scenario, when the regime’s end turns into a large‑scale civil‑military conflict over a vast territory, future reformers may face radical regionalism, whose leaders, while agreeing to preserve the federation, will insist on the priority of local legislation and local, including religious, interpretation of rights. In both cases, potential liberal‑democratic reforms will have to take the prevailing circumstances into account and adapt to them.

Let us try to walk through the key processes. Naturally, the zero‑level task is to stop military actions in Ukraine and begin the negotiation process. The second “zero” task is to establish control — at least a degree of authority — over the Russian Armed Forces and Rosgvardia in order to order (or as necessary contain) the possible employment of military force within Russia.

The lessons of the first transit are analyzed in Chapters 1 and 3, and this analysis is aimed at helping the next generation of politicians to avoid repeating the mistakes already made; however, it is also necessary to anticipate new problems, and to have ideas and tools ready to solve them.

Putin’s death or any other removal from power does not mean that the new Kremlin authorities will decide the morning after to repeal all his laws, release political prisoners, welcome back those in exile, and call free elections. On the contrary, it is much more likely that immediately after Putin’s departure the regime will need a forceful reinforcement and tightening of domestic politics, since Putin’s successor will need — even with the best future intentions — to first consolidate his own power and ensure its survival and stability. We proceed from the assumption that Putin’s “sudden” successor will not be interested in continuing the war in Ukraine — but we do not rule out the possibility that the continuation of the war may be the only tool to achieve consensus in the ruling elite. Also, the current economic situation in Russia is not acutely crisis‑ridden, but the possibility of a sharp escalation of socio‑economic tensions cannot be ruled out, which will certainly shape the available policy options.

The long “autumn of the patriarch”, continuing as another presidential term of Vladimir Putin (who will turn 78 at the end of this period, exactly as Stalin did in 1953), will no doubt complicate any attempt to return the Russian Federation as a whole to the path of democratic transit.

In the scenario of a rapid (within a year) change of power it makes sense to talk about the sequence of actions within the framework of a unified Russian state, in which case it will be necessary to restore normal federal relations. In the second scenario, the central issue is likely to be that of moderating the disintegrating imperial state, parts of which will seek to separate from it at all costs, while chauvinistic and xenophobic sentiments are simultaneously growing.

As it seems to us, any periodization and definition of the sequence of actions in the event that Russia starts moving towards a new period of democratic transit must proceed from the fact that such a movement will have 4 (5 at most) stages:

The stage of long‑term preparation, which has been underway for several years, including through the efforts of such projects as Reforum, Re:Russia and some others. At the same time, it is necessary to conduct political work, both in exile and inside Russia, to build consensus around the general direction of reforms, and to create potential framework coalitions and alliances that can be activated as soon as the situation allows.

The stage of power jockeying in a moment of crisis; no matter how Vladimir Putin’s personal regime ends, it is unlikely that his potential successors will have elaborate plans for what should be done after his departure. The readiness of the successor regime to dismantle Putin’s repressive legacy will open up limited opportunities to offer him reasonable plans and roadmaps thought out in the previous period. The existence of proto‑unions of political forces that, on the one hand, represent significant groups of the population and, on the other hand, have a more ready and perfect agenda for future changes, will allow the liberal group to increase its weight in the future inevitable roundtable.

The stage of the “round table” occurs when various political forces negotiate the rules for a return to a civil, electoral, representative democratic regime. The reasons why an authoritarian power agrees to the “round table” format are usually related to mass discontent and economic and social crises, which cannot be suppressed with brute force. The experience of Spain and Poland in the 1980s is particularly relevant for a future Russia, since in both cases the democratization of fairly rigid authoritarian regimes took place (in the case of Poland, with the presence of Soviet troops). This format, especially in a situation where a weakening authoritarian power agrees to negotiations under pressure, is characterized by the gradual “migration” of legitimacy and actual power from the dictator (or party) into the hands of institutions, the creation of which is agreed upon within the framework of the “round table.“ It is likely (albeit not necessary) that during this period, the final dismantling of the quasi‑institutions created by the Putin regime will take place, along with the formation of new ones, possibly based on the principles proposed by liberals. It is important to note that the “round table” format typically emerges as a gesture of goodwill from the hegemon (or the authorities), whether compelled or voluntary. Generally, this approach serves as a means to avoid revolutionary violence as a method of regime change and to offer specific guarantees to representatives of authoritarian or totalitarian power after free elections.

The “new parliament” stage, when all or part of the mutually agreed proposals will be introduced in the legislature and enacted into law, with liberal factions able to push for the interests of their constituents and the democratic order of the country as a whole.

The stage of a government of national confidence, when, as a result of elections, all or a majority of political forces will find it possible to agree for a certain period to a broad coalition government, with cooperation both in parliament and local governments, so as to “heal” society and the country from the wounds and pathologies inflicted by the Putin regime. Such an agreement would be an ideal format for putting Russia back on the path of democratic transit.

Despite the significant differences between the circumstances that will accompany the new launch of the democratic transition “earlier” and “much later,” there are common fundamental problems in both cases. For example, in the first scenario, it is quite likely that, in order to consolidate power and eliminate political unrest, the potential successor to Putin will have to impose martial law, completely abolishing civil liberties. Despite the radical anti‑democratic nature of such measures, they may be beneficial for getting rid of some individuals and institutions (quasi‑institutions) that emerged under Putin. However, the range of political forces that the interim regime deems acceptable to discuss the future with may also be reduced. On the contrary, in the second scenario, when the regime’s end turns into a large‑scale civil‑military conflict over a vast territory, future reformers may face radical regionalism, whose leaders, while agreeing to preserve the federation, will insist on the priority of local legislation and local, including religious, interpretation of rights. In both cases, potential liberal‑democratic reforms will have to take the prevailing circumstances into account and adapt to them.

Let us try to walk through the key processes. Naturally, the zero‑level task is to stop military actions in Ukraine and begin the negotiation process. The second “zero” task is to establish control — at least a degree of authority — over the Russian Armed Forces and Rosgvardia in order to order (or as necessary contain) the possible employment of military force within Russia.

Regardless of when and how Putin is “subtracted” and regime change begins, a key condition for moving toward a more open, and as a result, potentially democratic state in Russia would be the decision to abolish all repressive legislation passed in the Russian Federation after at least 2011 (the end of the term of the last relatively legitimate State Duma). Without fulfillment of this condition, such crucial actions for the future of the country as release and rehabilitation of all political prisoners convicted under the laws passed by the illegitimate State Duma and investigation of law enforcement officials (FSB, MVD, IC and others) who used the repealed legislation for political persecution would be impossible.

The dismantling of repressive legislation would also entail the abolition of the status of “undesirable organizations” and “foreign agents”, thus [1] opening the way for the participation in the political life of Russia of organizations and persons previously marked with these “stigmas”, and [2] removing the impediments to financing political activities from outside (perhaps for a specified period of time).

Regardless of when and how Putin is “subtracted” and regime change begins, a key condition for moving toward a more open, and as a result, potentially democratic state in Russia would be the decision to abolish all repressive legislation passed in the Russian Federation after at least 2011 (the end of the term of the last relatively legitimate State Duma). Without fulfillment of this condition, such crucial actions for the future of the country as release and rehabilitation of all political prisoners convicted under the laws passed by the illegitimate State Duma and investigation of law enforcement officials (FSB, MVD, IC and others) who used the repealed legislation for political persecution would be impossible.

The dismantling of repressive legislation would also entail the abolition of the status of “undesirable organizations” and “foreign agents”, thus [1] opening the way for the participation in the political life of Russia of organizations and persons previously marked with these “stigmas”, and [2] removing the impediments to financing political activities from outside (perhaps for a specified period of time).

In itself, the formation of the Round Table structure will mean the return to a socio‑political process permitting return to positions of power and influence of those who were victims of unlawful repression. At the same time, however partially, any leader or group of leaders who seek to change the course of the post‑Putin state in the direction of liberalization will likely have been to some degree complicit in the illegal and criminal actions of the regime BEFORE the process of national reconciliation and harmony begins. With that in mind, opposition leaders must agree to a certain level of cooperation with post‑Putin officials participating in the transition process in advance. While demands for lustration and prosecution of many individuals and groups within Putin’s entourage would be justified, their decision to agree to democratize the country ought to be understood as a manifestation of goodwill, even if they are arguably doing so not so much out of altruism as for selfish reasons (preservation of capital gained during Putin’s time, the possibility of avoiding lustration and even more so criminal prosecution, etc.).

If possible, in the process of coordinating the agenda of the Round Table, agreements should be reached on the formation of a temporary non‑party government with sufficient powers to manage the economy of the Russian Federation, along with the mandatory creation — most likely with the participation of the widest possible range of political forces — of temporary bodies of civilian control over the Armed Forces, Rosgvardia and other paramilitary state organizations, primarily the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Federal Penitentiary Service of the Russian Federation.

In itself, the formation of the Round Table structure will mean the return to a socio‑political process permitting return to positions of power and influence of those who were victims of unlawful repression. At the same time, however partially, any leader or group of leaders who seek to change the course of the post‑Putin state in the direction of liberalization will likely have been to some degree complicit in the illegal and criminal actions of the regime BEFORE the process of national reconciliation and harmony begins. With that in mind, opposition leaders must agree to a certain level of cooperation with post‑Putin officials participating in the transition process in advance. While demands for lustration and prosecution of many individuals and groups within Putin’s entourage would be justified, their decision to agree to democratize the country ought to be understood as a manifestation of goodwill, even if they are arguably doing so not so much out of altruism as for selfish reasons (preservation of capital gained during Putin’s time, the possibility of avoiding lustration and even more so criminal prosecution, etc.).

If possible, in the process of coordinating the agenda of the Round Table, agreements should be reached on the formation of a temporary non‑party government with sufficient powers to manage the economy of the Russian Federation, along with the mandatory creation — most likely with the participation of the widest possible range of political forces — of temporary bodies of civilian control over the Armed Forces, Rosgvardia and other paramilitary state organizations, primarily the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Federal Penitentiary Service of the Russian Federation.

One of the primary tasks of the Round Table will be the reform of the judiciary. The court system established in 2003–2023 and especially the selection of judges should be abolished and replaced by an interim structure that, in the meantime, is able to provide primary justice in most criminal, civil and family cases. It is likely that transitional justice should be limited in both duration and competence, with any complex cases (including those with potential jury trials) deferred until full courts of all instances have been established.

In the period of transitional justice, the key role will be played by courts of first and cassation instances, which should be constituted from citizens having a legal education, but not involved in any way in repressive acts of the previous period.

One of the primary tasks of the Round Table will be the reform of the judiciary. The court system established in 2003–2023 and especially the selection of judges should be abolished and replaced by an interim structure that, in the meantime, is able to provide primary justice in most criminal, civil and family cases. It is likely that transitional justice should be limited in both duration and competence, with any complex cases (including those with potential jury trials) deferred until full courts of all instances have been established.

In the period of transitional justice, the key role will be played by courts of first and cassation instances, which should be constituted from citizens having a legal education, but not involved in any way in repressive acts of the previous period.

This point, in the event that the second transit scenario takes place (“long autumn of the patriarch”), will most likely become the first. The existence of the state “Russian Federation” (in approximately modern borders) will be possible only if the conditions favorable to the national regions are defined and fixed in the new Federal Treaty, which should be agreed and adopted in advance of the Constitution, not a part or a consequence of it. Accordingly, the problem of the structure of the federation, the division and balance of powers between the constituent entities and the federal government, the issues of admission, withdrawal and exclusion of the constituent entities from the Federation should be weighed and fully grasped long before this problem comes to the center of attention. The draft Federal Treaty should be prepared and initially agreed upon in the course of the Round Table’s activities, since only through mutual assent of multiple parties in re‑establishing the Federation will it be possible to define legal formulas in terms of federal, regional and local powers, issues of joint jurisdiction, and guarantees of regional representation in the federal legislature, which must be formally incorporated into both the future Constitution and constitutional laws.

This point, in the event that the second transit scenario takes place (“long autumn of the patriarch”), will most likely become the first. The existence of the state “Russian Federation” (in approximately modern borders) will be possible only if the conditions favorable to the national regions are defined and fixed in the new Federal Treaty, which should be agreed and adopted in advance of the Constitution, not a part or a consequence of it. Accordingly, the problem of the structure of the federation, the division and balance of powers between the constituent entities and the federal government, the issues of admission, withdrawal and exclusion of the constituent entities from the Federation should be weighed and fully grasped long before this problem comes to the center of attention. The draft Federal Treaty should be prepared and initially agreed upon in the course of the Round Table’s activities, since only through mutual assent of multiple parties in re‑establishing the Federation will it be possible to define legal formulas in terms of federal, regional and local powers, issues of joint jurisdiction, and guarantees of regional representation in the federal legislature, which must be formally incorporated into both the future Constitution and constitutional laws.

Most likely, the Round Table will come to a consensus that the new Russia (Russian Federation) will need a completely new version of the Basic Law. The most likely solution would be to form one or more working groups consisting of legal scholars and politicians who would propose basic versions of a new Constitution‑Main Law (based on the agreements at the Round Table, e.g., on parliamentary or presidential‑parliamentary forms of government). At the same time, the Round Table should determine the terms, parameters and rules for the formation of a Constitutional Council authorized to adopt (and in the future, to amend and modify) the Basic Law. The decisions of the Round Table should be as close as possible to the future laws (sections of the Constitution) determining its adoption, amendments and additions.

Most likely, the Round Table will come to a consensus that the new Russia (Russian Federation) will need a completely new version of the Basic Law. The most likely solution would be to form one or more working groups consisting of legal scholars and politicians who would propose basic versions of a new Constitution‑Main Law (based on the agreements at the Round Table, e.g., on parliamentary or presidential‑parliamentary forms of government). At the same time, the Round Table should determine the terms, parameters and rules for the formation of a Constitutional Council authorized to adopt (and in the future, to amend and modify) the Basic Law. The decisions of the Round Table should be as close as possible to the future laws (sections of the Constitution) determining its adoption, amendments and additions.

In addition to issues of constitutional construction, the Round Table should agree on a whole group of issues related to the will of the citizens (other than approval of the Constitution, if it is decided to approve the Basic Law by direct vote of citizens). Depending on the decisions made, for example, it will be possible (or not) to combine referendums with voting on federal, regional and local elections. Among other things, initial decisions on whether or not the formation of electoral blocs is permissible, the powers of election commissions in the first elections (they should be significantly expanded compared to previous versions), and the procedures for resolving disputes and conflicts should be elaborated and adopted.

In addition to issues of constitutional construction, the Round Table should agree on a whole group of issues related to the will of the citizens (other than approval of the Constitution, if it is decided to approve the Basic Law by direct vote of citizens). Depending on the decisions made, for example, it will be possible (or not) to combine referendums with voting on federal, regional and local elections. Among other things, initial decisions on whether or not the formation of electoral blocs is permissible, the powers of election commissions in the first elections (they should be significantly expanded compared to previous versions), and the procedures for resolving disputes and conflicts should be elaborated and adopted.

Given the peculiarities of Russian political history, one of the most important tasks of the pre‑election work of liberal forces is the additional, explicit constitution of civil rights and freedoms necessary to resist usurpation of power, political domination and autocracy. Additional regulation will be needed, incorporated into the Basic Law as directly applicable legislation prohibiting any restrictions on freedom of speech, assembly, protest, parties and other public associations. In fact, the future Russia needs an analog of the Bill of Rights, inseparable from the Constitution, but specifically designed to make judicial revision of its provisions impossible.

Given the peculiarities of Russian political history, one of the most important tasks of the pre‑election work of liberal forces is the additional, explicit constitution of civil rights and freedoms necessary to resist usurpation of power, political domination and autocracy. Additional regulation will be needed, incorporated into the Basic Law as directly applicable legislation prohibiting any restrictions on freedom of speech, assembly, protest, parties and other public associations. In fact, the future Russia needs an analog of the Bill of Rights, inseparable from the Constitution, but specifically designed to make judicial revision of its provisions impossible.

Liberal forces will represent an insignificant (at first) group of Russian voters, but it is crucial that this faction has a program of action — in terms of legislation, social state, human rights, international relations, etc. — to expand its electoral base. Counting on anything more than a minority faction in the first iterations of the new Russian parliament is certainly no better than believing in a world of pink ponies and unicorns. However, the key task of the liberal minority is to uphold the principles of the institutional structure of the state, meritocracy, the triumph and prevalence of laws, and the political neutrality of the law enforcement system.

As noted above, the order of tasks to restructure the political and legal system will differ if the changes begin earlier (within the 12‑month horizon) and later, at the end of or beyond the next term of Vladimir Putin’s presidency (beyond the 6‑year horizon).

Accordingly, additional specific tasks for the “relatively near‑term” option should be based on the circumstances that are currently affecting Russia’s domestic and foreign policy, with the need for a substantial course correction as soon as possible.

In addition to constitutional reform and the transition to a balanced institutional system of government, the liberal and democratic forces' tasks include, with high priority, the task of restoring international relations, especially with regard to those countries that Putin’s regime calls “unfriendly,“ while at the same time clearly controlling the “eastern direction” of Russian foreign policy in order to prevent (at the very least) Chinese discontent with Russia’s possible return to the West’s sphere of influence. Most likely, Putin’s potential successor will also — after consolidation of power — be interested in at least moving relations with the West in a constructive direction. This will require not only replacing diplomatic representatives in the respective countries, but also restructuring the Foreign Ministry and its relations with intelligence and security agencies. And this task is important precisely for the early transition period because, among other goals, post‑Putin Russia must convince the key opponents of its policy in Putin’s last years that the turnaround is being carried out, in Lenin’s words, “seriously and for a long time”.

An important goal of the constructive forces in the “relatively near‑term” version, comparable to the main legislative and institutional tasks, will be to restore public confidence in the values of democracy, competitive politics, and respect for human rights. A decade of Putin’s propaganda has taken a toll: significant groups of the population are immersed in a state of anti‑democratic resentment, the word “liberal” is now a swear word for many Russians, and human rights exist only in relation to oneself. The issues of restoring confidence in democracy and liberal values, as well as the complexity of such activities, are separately addressed in Chapter 9, and the problems of restoring individual and citizen rights, as well as respect for them, are addressed in Chapter 4. However, speaking precisely about the place of this work in the priorities of Russia’s future return to the path of democratic transit, political forces need to exercise restraint, not use propaganda techniques, and strive to develop citizens' interest in participating in political activity, rather than “reprogramming” them with the same means by which Putin and his media machine have brought Russians to such a life.

It is hoped that Vladimir Putin’s potential successor will be interested (марк)in ending the war in Ukraine and achieving a consensual peace settlement.(/мрак) It is quite likely that the initial resolution of the military phase will take place even before the involvement of democratic forces; for obvious reasons, under the interim military dictatorship that the successor will need to consolidate power, it will be easier (if at all) to explain the reasons for an outcome of the war unfavorable to Russia and to suppress possible resistance and inevitable conflicts.

In any case, in the “relatively near‑term” variant, it will require complex and serious political work to moderate the consequences of the war, both in terms of compensating Ukraine for the material damage caused, and in terms of treating Russian society for the traumas suffered during the war. We cannot predict the exact moment at which hostilities will stop, the state of the Armed Forces, much less whether radical pro‑militarist forces will resist the policy of ending the war. On the other hand, no matter how great and obvious the guilt of the Russian authorities in unleashing and waging a war of aggression, the excessive desire to “at any cost” to make amends and punish those responsible will clearly not contribute to a positive public opinion, which, alas, will have to be prepared and persuaded for a long time to accept the relevant decisions as a given.

Liberal forces will represent an insignificant (at first) group of Russian voters, but it is crucial that this faction has a program of action — in terms of legislation, social state, human rights, international relations, etc. — to expand its electoral base. Counting on anything more than a minority faction in the first iterations of the new Russian parliament is certainly no better than believing in a world of pink ponies and unicorns. However, the key task of the liberal minority is to uphold the principles of the institutional structure of the state, meritocracy, the triumph and prevalence of laws, and the political neutrality of the law enforcement system.

As noted above, the order of tasks to restructure the political and legal system will differ if the changes begin earlier (within the 12‑month horizon) and later, at the end of or beyond the next term of Vladimir Putin’s presidency (beyond the 6‑year horizon).

Accordingly, additional specific tasks for the “relatively near‑term” option should be based on the circumstances that are currently affecting Russia’s domestic and foreign policy, with the need for a substantial course correction as soon as possible.

In addition to constitutional reform and the transition to a balanced institutional system of government, the liberal and democratic forces' tasks include, with high priority, the task of restoring international relations, especially with regard to those countries that Putin’s regime calls “unfriendly,” while at the same time clearly controlling the “eastern direction” of Russian foreign policy in order to prevent (at the very least) Chinese discontent with Russia’s possible return to the West’s sphere of influence. Most likely, Putin’s potential successor will also — after consolidation of power — be interested in at least moving relations with the West in a constructive direction. This will require not only replacing diplomatic representatives in the respective countries, but also restructuring the Foreign Ministry and its relations with intelligence and security agencies. And this task is important precisely for the early transition period because, among other goals, post‑Putin Russia must convince the key opponents of its policy in Putin’s last years that the turnaround is being carried out, in Lenin’s words, “seriously and for a long time”.

An important goal of the constructive forces in the “relatively near‑term” version, comparable to the main legislative and institutional tasks, will be to restore public confidence in the values of democracy, competitive politics, and respect for human rights. A decade of Putin’s propaganda has taken a toll: significant groups of the population are immersed in a state of anti‑democratic resentment, the word “liberal” is now a swear word for many Russians, and human rights exist only in relation to oneself. The issues of restoring confidence in democracy and liberal values, as well as the complexity of such activities, are separately addressed in Chapter 9, and the problems of restoring individual and citizen rights, as well as respect for them, are addressed in Chapter 4. However, speaking precisely about the place of this work in the priorities of Russia’s future return to the path of democratic transit, political forces need to exercise restraint, not use propaganda techniques, and strive to develop citizens' interest in participating in political activity, rather than “reprogramming” them with the same means by which Putin and his media machine have brought Russians to such a life.

It is hoped that Vladimir Putin’s potential successor will be interested (марк)in ending the war in Ukraine and achieving a consensual peace settlement.(/мрак) It is quite likely that the initial resolution of the military phase will take place even before the involvement of democratic forces; for obvious reasons, under the interim military dictatorship that the successor will need to consolidate power, it will be easier (if at all) to explain the reasons for an outcome of the war unfavorable to Russia and to suppress possible resistance and inevitable conflicts.

In any case, in the “relatively near‑term” variant, it will require complex and serious political work to moderate the consequences of the war, both in terms of compensating Ukraine for the material damage caused, and in terms of treating Russian society for the traumas suffered during the war. We cannot predict the exact moment at which hostilities will stop, the state of the Armed Forces, much less whether radical pro‑militarist forces will resist the policy of ending the war. On the other hand, no matter how great and obvious the guilt of the Russian authorities in unleashing and waging a war of aggression, the excessive desire to “at any cost” to make amends and punish those responsible will clearly not contribute to a positive public opinion, which, alas, will have to be prepared and persuaded for a long time to accept the relevant decisions as a given.

What will Russia be like if Vladimir Putin rules the country for another 6 years or more? In what state will society approach the biologically inevitable end of the regime? Will the war in Ukraine end in the lifetime of its initiator? How far can Russia’s isolation and self‑isolation go? How will this isolation affect the economy, science, education and culture? In many respects, the tasks of the “long variant” will be determined by the answers to these questions, but we can, using extrapolation, assume that:

What will Russia be like if Vladimir Putin rules the country for another 6 years or more? In what state will society approach the biologically inevitable end of the regime? Will the war in Ukraine end in the lifetime of its initiator? How far can Russia’s isolation and self‑isolation go? How will this isolation affect the economy, science, education and culture? In many respects, the tasks of the “long variant” will be determined by the answers to these questions, but we can, using extrapolation, assume that:

Clearly, these are more than general, broad images, and the specific details of the “long autumn of the patriarch” will depend on many factors, including those unknown to us today. In any case, it seems to us that by the end of Putin’s next term, the Russian Federation will be a weakened but militarized state, with a pile of internal conflicts, including suppressed ones, and in a high degree of isolation from the rest of the world. Internal problems in the economy, in the psychological state of significant groups of the population traumatized to a greater or lesser extent by the war in Ukraine (God willing, only in Ukraine), degrading education, medicine, science and culture — while Putin and the population are told by the same propaganda about the unprecedented prosperity of everything, first of all, the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation.

As bleak as this picture may seem, it describes a highly unstable state that could be undermined by any acute crisis at the center of power — which is likely to happen when, amid the physical end of Vladimir Putin’s life, factions within his entourage begin to divide the falling wreckage of power. The escalating contradictions will, unfortunately, lead to almost inevitable violence, localized conflicts and, almost inevitably, the growth of separatist sentiments in the regions.

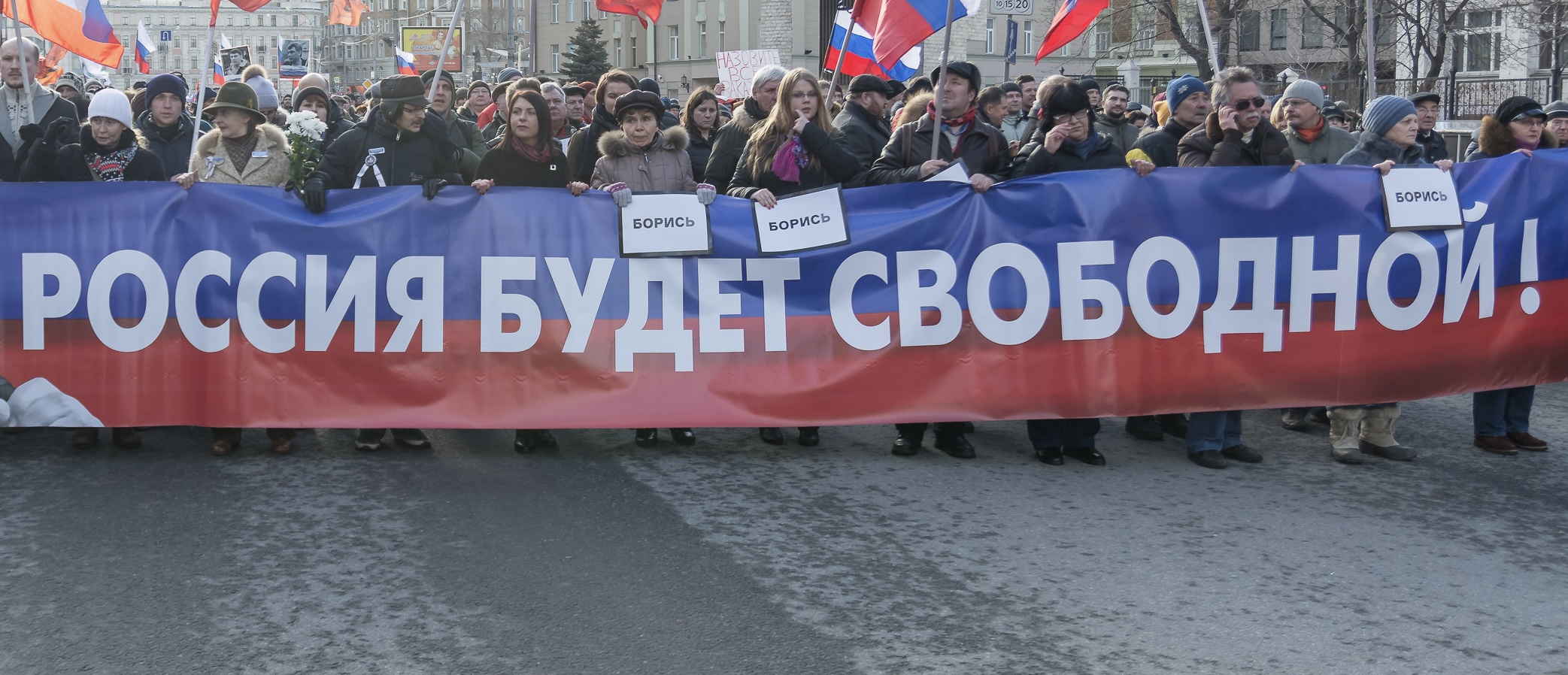

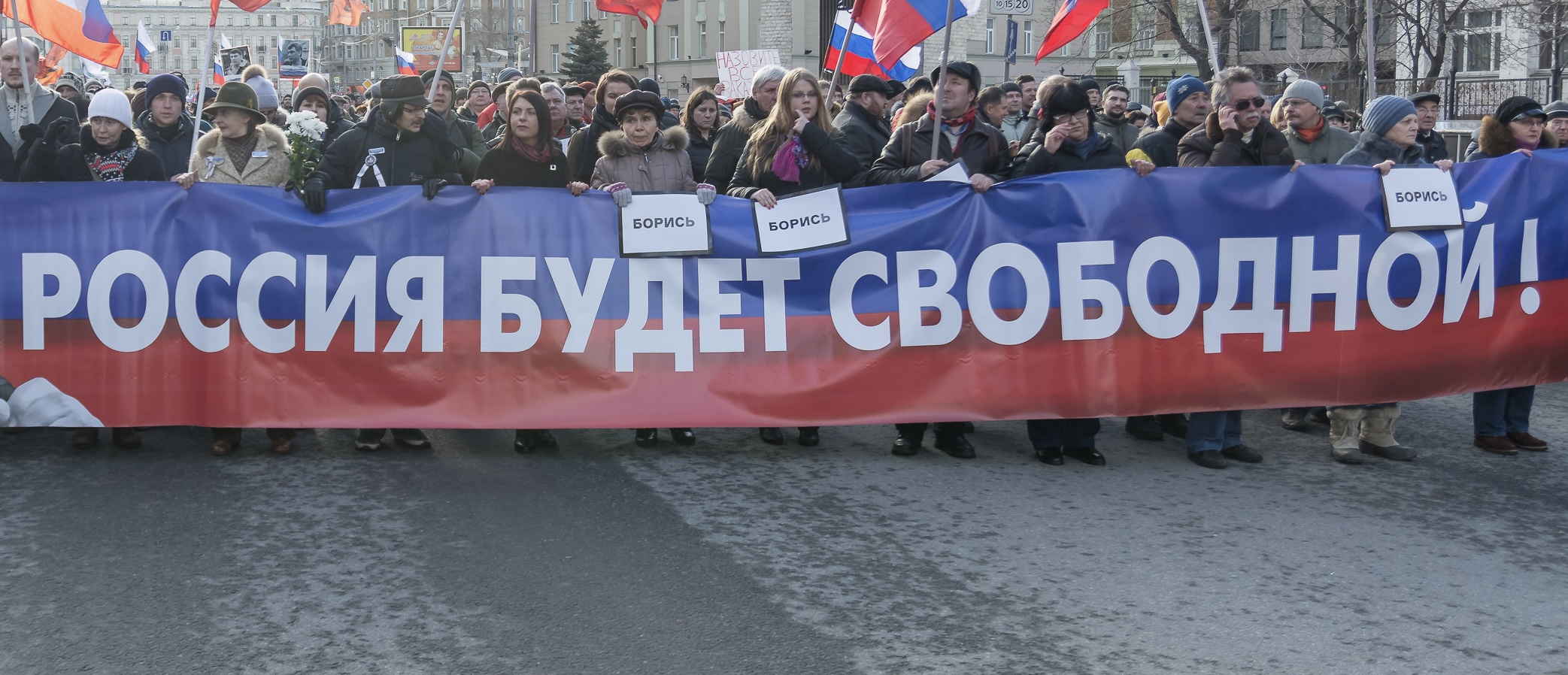

In the “long variant” the way to launch the transit is most likely through the growth of political tension in the largest cities of the country — and the open use of violence, especially factional violence (we pointed out above that factions from Putin’s entourage are fighting for power), provokes the growth of unrest, large unorganized and then, possibly, organized demonstrations. The likelihood of localized unification of opponents of the authorities across the broad political spectrum becomes higher, and the ability to use suppression by the authorities becomes less, and a local transition of power is likely to occur, with the largest cities coming under the control of the protesters and their political leaders. At the same time, the events in Moscow, St. Petersburg or Novosibirsk are not synchronized and have different slogans, except for the main one — the desire for greater independence and autonomy of the regional authorities. In addition to the crisis of “factions” in Putin’s power‑sharing entourage, the country is plunged into a specific “parade of sovereignties,“ in which the federal center is rapidly losing resources, primarily military and power resources. The army is actually leaving the front, seeking to participate in the division of Putin’s inheritance and power — in formations and individually (but with weapons).

We do not know exactly what kind of tortuous path Russia might then take to begin transit again, but the conditions under which reforms will be needed are fairly predictable. The process, which in this case can really be called “saving Russia,” can only be led by a decisive leader capable of negotiation and alliance‑building, interested in stopping the chaos, in turning the “war of all against all.“ He may be a democratic idealist, but initially he will have to implement the agenda of consolidating power at least to the extent that will allow him to move from authoritarian politics to the re‑formalization of the Federation and the re‑establishment of the state.

In a certain sense, it is less problematic than, as in the “relatively near‑term” version, sawing out a new Russia from the array of layers, from the empire to Putin — many laws and rules will simply be abolished without much bowing to the remnants of the previous regime (or regimes), the reconstitution of the Federation can be launched immediately, dissolving the previous version and declaring a new one — voluntary for all regions, with their own vision of autonomy and regional organization.

In contrast to the “relatively near‑term” variant, in which the need to cooperate with the past is obvious, the military‑revolutionary development of the situation requires only the presence of a clear idea, political will and the force that realizes it — apparently, as in 1918, some kind of “revolutionary guard” protecting the new regime, but limited in existence in time, until the restoration of law and order.

In fact, the consequences of the “long option” will require the creation of the state “from below” — through local self‑government (which will inevitably be strengthened in the process of crisis), to the regional level (which must be reconstituted to resolve the question of membership in the Federation), and only then to the formulation of the idea of a federal‑level organization.

Only after the federal relationship is built anew can we move from temporary solutions for organizing the country to permanent ones — with the same general components.

Clearly, these are more than general, broad images, and the specific details of the “long autumn of the patriarch” will depend on many factors, including those unknown to us today. In any case, it seems to us that by the end of Putin’s next term, the Russian Federation will be a weakened but militarized state, with a pile of internal conflicts, including suppressed ones, and in a high degree of isolation from the rest of the world. Internal problems in the economy, in the psychological state of significant groups of the population traumatized to a greater or lesser extent by the war in Ukraine (God willing, only in Ukraine), degrading education, medicine, science and culture — while Putin and the population are told by the same propaganda about the unprecedented prosperity of everything, first of all, the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation.

As bleak as this picture may seem, it describes a highly unstable state that could be undermined by any acute crisis at the center of power — which is likely to happen when, amid the physical end of Vladimir Putin’s life, factions within his entourage begin to divide the falling wreckage of power. The escalating contradictions will, unfortunately, lead to almost inevitable violence, localized conflicts and, almost inevitably, the growth of separatist sentiments in the regions.

In the “long variant” the way to launch the transit is most likely through the growth of political tension in the largest cities of the country — and the open use of violence, especially factional violence (we pointed out above that factions from Putin’s entourage are fighting for power), provokes the growth of unrest, large unorganized and then, possibly, organized demonstrations. The likelihood of localized unification of opponents of the authorities across the broad political spectrum becomes higher, and the ability to use suppression by the authorities becomes less, and a local transition of power is likely to occur, with the largest cities coming under the control of the protesters and their political leaders. At the same time, the events in Moscow, St. Petersburg or Novosibirsk are not synchronized and have different slogans, except for the main one — the desire for greater independence and autonomy of the regional authorities. In addition to the crisis of “factions” in Putin’s power‑sharing entourage, the country is plunged into a specific “parade of sovereignties,” in which the federal center is rapidly losing resources, primarily military and power resources. The army is actually leaving the front, seeking to participate in the division of Putin’s inheritance and power — in formations and individually (but with weapons).

We do not know exactly what kind of tortuous path Russia might then take to begin transit again, but the conditions under which reforms will be needed are fairly predictable. The process, which in this case can really be called “saving Russia,“ can only be led by a decisive leader capable of negotiation and alliance‑building, interested in stopping the chaos, in turning the “war of all against all.” He may be a democratic idealist, but initially he will have to implement the agenda of consolidating power at least to the extent that will allow him to move from authoritarian politics to the re‑formalization of the Federation and the re‑establishment of the state.

In a certain sense, it is less problematic than, as in the “relatively near‑term” version, sawing out a new Russia from the array of layers, from the empire to Putin — many laws and rules will simply be abolished without much bowing to the remnants of the previous regime (or regimes), the reconstitution of the Federation can be launched immediately, dissolving the previous version and declaring a new one — voluntary for all regions, with their own vision of autonomy and regional organization.

In contrast to the “relatively near‑term” variant, in which the need to cooperate with the past is obvious, the military‑revolutionary development of the situation requires only the presence of a clear idea, political will and the force that realizes it — apparently, as in 1918, some kind of “revolutionary guard” protecting the new regime, but limited in existence in time, until the restoration of law and order.

In fact, the consequences of the “long option” will require the creation of the state “from below” — through local self‑government (which will inevitably be strengthened in the process of crisis), to the regional level (which must be reconstituted to resolve the question of membership in the Federation), and only then to the formulation of the idea of a federal‑level organization.

Only after the federal relationship is built anew can we move from temporary solutions for organizing the country to permanent ones — with the same general components.

Under what circumstances could the collapse of Putin’s regime occur, what will replace it?

By Vasiliy Zharkov

By Nikolay Petrov

May 29, 2024

Report

Report By Ekaterina Mishina

May 29, 2024

Report

Report What should be done to reconstruct rights and freedoms?

By Olga Khvostunova

May 29, 2024

Under what circumstances could the collapse of Putin’s regime occur, what will replace it?

By Vasiliy Zharkov

By Nikolay Petrov

May 29, 2024

Report

Report By Ekaterina Mishina

May 29, 2024

Report

Report What should be done to reconstruct rights and freedoms?

By Olga Khvostunova

May 29, 2024