How independent media emerge and change during the war in Ukraine

By Free Russia Foundation June 21, 2023

By Free Russia Foundation June 21, 2023

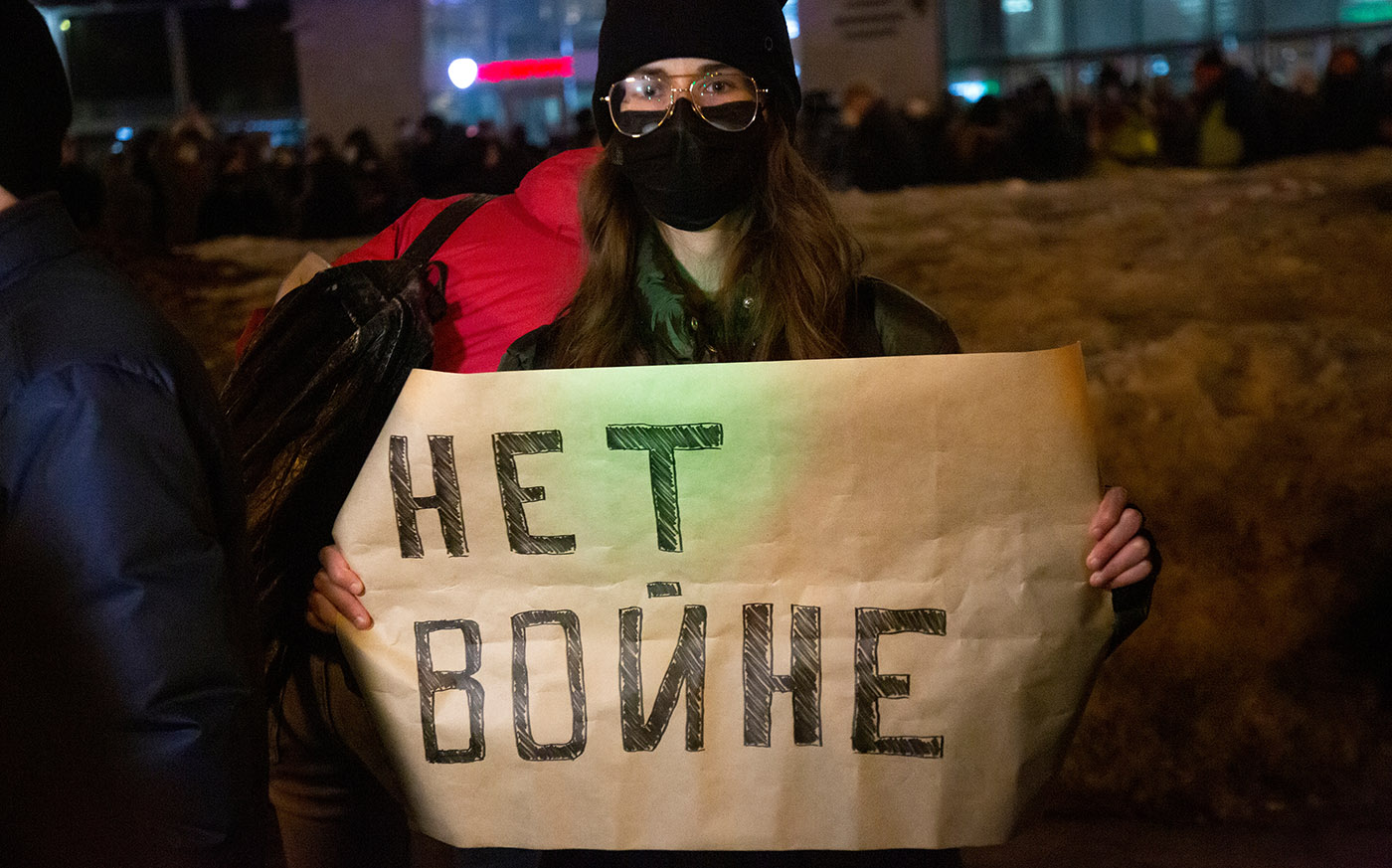

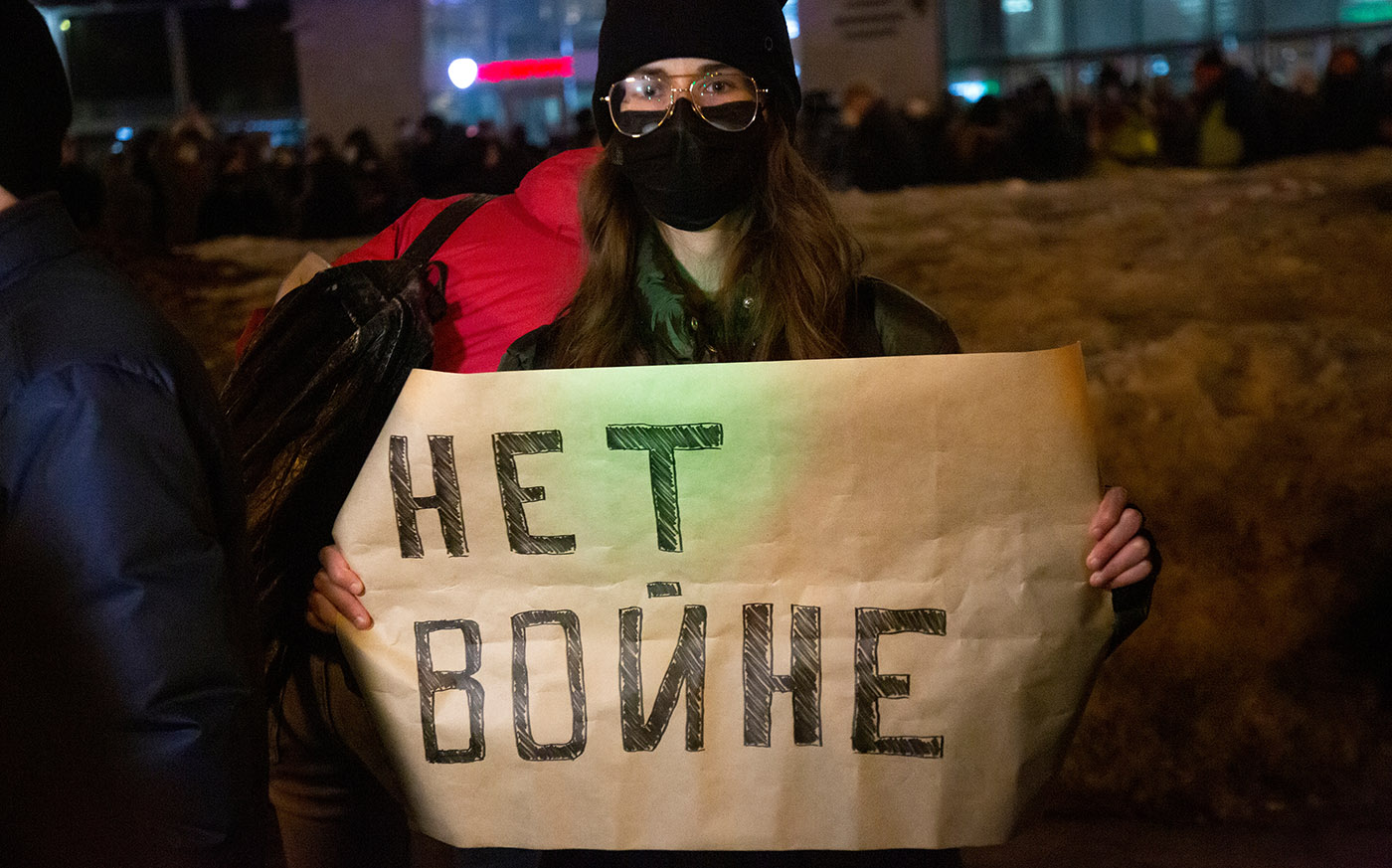

On February 24, 2022, war censorship was de facto established in Russia: Roskomnadzor, the government’s media watchdog, demanded that the media and information resources that cover the situation in Ukraine cite only official sources. For spreading what the Russian authorities deem as “deliberately false information,“ media outlets could be blocked and fined.

Over a year and a half, Roskomnadzor blocked more than 10,000 sites, dozens of independent publications were declared foreign agents and “undesirable organizations.” About 15 editorial offices moved abroad, some were forced to shut down, some changed their format. Two dozen of the new Russian‑language media were launched as well: journalists sought to understand what was unraveling as a result of the war and cover it.

These newly emerging media are organized and function differently compared to their old counterparts‑they have a different relationship with their audience. The search for a new language, focus on people’s stories, and mutual support make their work possible and even successful.

On February 24, 2022, war censorship was de facto established in Russia: Roskomnadzor, the government’s media watchdog, demanded that the media and information resources that cover the situation in Ukraine cite only official sources. For spreading what the Russian authorities deem as “deliberately false information,“ media outlets could be blocked and fined.

Over a year and a half, Roskomnadzor blocked more than 10,000 sites, dozens of independent publications were declared foreign agents and “undesirable organizations.” About 15 editorial offices moved abroad, some were forced to shut down, some changed their format. Two dozen of the new Russian‑language media were launched as well: journalists sought to understand what was unraveling as a result of the war and cover it.

These newly emerging media are organized and function differently compared to their old counterparts‑they have a different relationship with their audience. The search for a new language, focus on people’s stories, and mutual support make their work possible and even successful.

New media began to emerge immediately after the Russian full‑fledged invasion of Ukraine and the introduction of war censorship. On March 5, 2022, the Astra Telegram channel was launched: its team publishes news, videos and photos, eyewitness accounts, interviews with Ukrainians and Russians affected by the war, and conducts investigations.

In April, one of the first socio‑political online publications in Russia Polit.Ru, creator and partner of many humanitarian projects, launched its project called After, which is dedicated to conversations “with various interesting people about possible options for the Russian future.”

At the end of April, another new publication, Verstka, was launched. Without initial funding or established audience, the team could only respond to readers' requests, according to its founder, journalist Lola Tagaeva, who spoke about it at the recent Brussels Dialogue forum.

New media began to emerge immediately after the Russian full‑fledged invasion of Ukraine and the introduction of war censorship. On March 5, 2022, the Astra Telegram channel was launched: its team publishes news, videos and photos, eyewitness accounts, interviews with Ukrainians and Russians affected by the war, and conducts investigations.

In April, one of the first socio‑political online publications in Russia Polit.Ru, creator and partner of many humanitarian projects, launched its project called After, which is dedicated to conversations “with various interesting people about possible options for the Russian future.”

At the end of April, another new publication, Verstka, was launched. Without initial funding or established audience, the team could only respond to readers' requests, according to its founder, journalist Lola Tagaeva, who spoke about it at the recent Brussels Dialogue forum.

“There is plenty of issues: the state creates problems for people every day and simultaneously imposes its agenda. We could not and cannot leave these people to be overcome by propaganda. They need free journalism. It turned out that if you answer [people’s questions] on time, if they get something first, readers come.“

“There is plenty of issues: the state creates problems for people every day and simultaneously imposes its agenda. We could not and cannot leave these people to be overcome by propaganda. They need free journalism. It turned out that if you answer [people’s questions] on time, if they get something first, readers come.“

On May 11, 2022, Ilya Krasilshchik, former publisher of Meduza and former head of Yandex. Lavka, a food delivery service, launched Helpdesk.Media, a media project and assistance service for the war victims in Ukraine and beyond. In March 2023, Ilya introduced the mobile app through which readers can set up a news feed, get support and donate to deliver urgent help to those in need.

At the end of May2022, the Cedar (Kedr) project was launched focusing on how the war affects the environment in Russia, Ukraine, and the world.

On June 1, Ochevidtsy (Eyewitnesses) was launched, offering a public platform for Russians and Ukrainians, both celebrities and ordinary people, to speak about the ways their lives have changed since the outbreak of the war. “There is this large‑scale historical event that will change the lives of many people forever,“ says one of the project’s creators Viktor Muchnik, former editor‑in-chief of the independent Tomsk television channel TV2. “And I have witnesses of these events‑ordinary people to whom I can come with a camera talk [about it].”

Political scientist Kirill Rogov and his team launched the Re:Russia project, an expert platform for discussing Russia’s political, social, and economic issues.

On May 11, 2022, Ilya Krasilshchik, former publisher of Meduza and former head of Yandex. Lavka, a food delivery service, launched Helpdesk.Media, a media project and assistance service for the war victims in Ukraine and beyond. In March 2023, Ilya introduced the mobile app through which readers can set up a news feed, get support and donate to deliver urgent help to those in need.

At the end of May2022, the Cedar (Kedr) project was launched focusing on how the war affects the environment in Russia, Ukraine, and the world.

On June 1, Ochevidtsy (Eyewitnesses) was launched, offering a public platform for Russians and Ukrainians, both celebrities and ordinary people, to speak about the ways their lives have changed since the outbreak of the war. “There is this large‑scale historical event that will change the lives of many people forever,” says one of the project’s creators Viktor Muchnik, former editor‑in-chief of the independent Tomsk television channel TV2. “And I have witnesses of these events‑ordinary people to whom I can come with a camera talk [about it].”

Political scientist Kirill Rogov and his team launched the Re:Russia project, an expert platform for discussing Russia’s political, social, and economic issues.

“Russia is at a tragic turning point in its history, the events taking place are comparable in significance, perhaps, only to the events of a century ago‑the Bolshevik coup and the civil war, because their consequences are likely to determine Russia’s place in the world and its historical track for decades to come. In this situation, a deep, non‑opportunistic understanding of the processes taking place in the country seems to be critically important and, in the end, can influence the future, exposing its imaginable scenarios and forks,“ the project manifesto says.

“Russia is at a tragic turning point in its history, the events taking place are comparable in significance, perhaps, only to the events of a century ago‑the Bolshevik coup and the civil war, because their consequences are likely to determine Russia’s place in the world and its historical track for decades to come. In this situation, a deep, non‑opportunistic understanding of the processes taking place in the country seems to be critically important and, in the end, can influence the future, exposing its imaginable scenarios and forks,” the project manifesto says.

Journalists Farida Rustamova and Maxim Tovkailo launched the Faridaily news channel:

Journalists Farida Rustamova and Maxim Tovkailo launched the Faridaily news channel:

“Today, simply informing the public to promote [certain] values is not enough. Direct communication with the audience is very important to us. Every day people write to me, saying ‘thank you for not leaving us alone.’ Russian officials also read [our channel], it is, too, important to keep in touch with them: not all of them are directly involved in the war crimes,“ Farida said during the Brussels Dialogue forum.

“Today, simply informing the public to promote [certain] values is not enough. Direct communication with the audience is very important to us. Every day people write to me, saying ‘thank you for not leaving us alone.’ Russian officials also read [our channel], it is, too, important to keep in touch with them: not all of them are directly involved in the war crimes,” Farida said during the Brussels Dialogue forum.

On June 30, 2022, the independent research media Beda (Disaster) was launched. The publication was founded by an anonymous team of journalists, translators, anthropologists and researchers, whose goal is to tell the stories of “those who have faced authoritarianism, military and police violence, exploitation and oppression,“ creating a knowledge‑based platform dedicated to Russian colonialism.

In the summer of 2022, Drone was launched, one of the few Russian‑language publications that does not only focus on news from Russia, but also covers events in Georgia, Moldova, Belarus and, of course, Ukraine.

Writer and journalist Linor Goralik and her team launched two anti‑war media projects‑News-26, a daily publication about Russian politics for teenagers, and ROAR (Russian Oppositional Arts Review), an online magazine that publishes literary and artistic work about the war in Ukraine.

This is, by no means, a complete list. Below are the projects that appeared instead of the ones that had been forced to shut down.

On June 30, 2022, the independent research media Beda (Disaster) was launched. The publication was founded by an anonymous team of journalists, translators, anthropologists and researchers, whose goal is to tell the stories of “those who have faced authoritarianism, military and police violence, exploitation and oppression,” creating a knowledge‑based platform dedicated to Russian colonialism.

In the summer of 2022, Drone was launched, one of the few Russian‑language publications that does not only focus on news from Russia, but also covers events in Georgia, Moldova, Belarus and, of course, Ukraine.

Writer and journalist Linor Goralik and her team launched two anti‑war media projects‑News-26, a daily publication about Russian politics for teenagers, and ROAR (Russian Oppositional Arts Review), an online magazine that publishes literary and artistic work about the war in Ukraine.

This is, by no means, a complete list. Below are the projects that appeared instead of the ones that had been forced to shut down.

The community of journalists who do not support the Putin regime was agile even before the war: many were familiar with each other, moved easily from one media to another; former colleagues launched their own projects (as happened, for example, with The Bell).

Overall, mutual support was strong. The closure of individual projects could have become a disaster, but the habit of reassembling, creating new associations and new formats has already been in place.

On March 1, 2022, at the request of Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office, the Echo of Moscow radio station stopped broadcasting. On October 3, the online edition of Echo was launched: the new media includes shows from YouTube channels of several editorial teams and independent journalists who previously collaborated with Echo of Moscow, including the Zhivoy Gvozd (Live Nail) channel.

Ilya Shepelin and Masha Borzunova, former employees of TV Rain (an independent television channel, which was forced to stop broadcasting in Russia and restarted abroad), created individual YouTube channels dedicated to exposing fake news.

The journalists of Novaya Gazeta who left Russia after the suspension of the publication on March 28, launched Novaya Gazeta Europe. The publication covers both Russian and European news, and also offers a Free Space service that allows readers to subscribe to the topics and authors of their interest. The editor‑in-chief of the new publication Kirill Martynov also writes weekly personal takes on recent Terrible News.

On March 6, 2022, Roskomnadzor blocked the website of the main publication of the Russian scientific community, Troitsky Variant‑Science, for publishing an anti‑war letter signed by more than 8,000 scientists‑one of the first statements by a professional community condemning the invasion. The T‑invariant project, edited by scientific journalist Olga Orlova, was relaunched in February 2023, focusing on science under the conditions of war in Ukraine.

The Bell project, created by a team of journalists who had departed leading Russian business publications Vedomosti and Forbes, launched the Telegram channel titled What do you get out of it?, which discusses how political economic news affect everyone on a personal level. Meduza also started a newsletter titled Signal, which explains the current developments instead of simply delivering facts, since “under the new conditions, the ability to understand news is not just useful, it is a vital skill.”

The St. Petersburg‑based Bumaga (Paper) created a newsletter titled Inhale. Exhale. Every evening, the publication recounts the events of the day, and then gives “one story about people that allows [readers] to look at the world with hope. It’s an exhale.“

The community of journalists who do not support the Putin regime was agile even before the war: many were familiar with each other, moved easily from one media to another; former colleagues launched their own projects (as happened, for example, with The Bell).

Overall, mutual support was strong. The closure of individual projects could have become a disaster, but the habit of reassembling, creating new associations and new formats has already been in place.

On March 1, 2022, at the request of Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office, the Echo of Moscow radio station stopped broadcasting. On October 3, the online edition of Echo was launched: the new media includes shows from YouTube channels of several editorial teams and independent journalists who previously collaborated with Echo of Moscow, including the Zhivoy Gvozd (Live Nail) channel.

Ilya Shepelin and Masha Borzunova, former employees of TV Rain (an independent television channel, which was forced to stop broadcasting in Russia and restarted abroad), created individual YouTube channels dedicated to exposing fake news.

The journalists of Novaya Gazeta who left Russia after the suspension of the publication on March 28, launched Novaya Gazeta Europe. The publication covers both Russian and European news, and also offers a Free Space service that allows readers to subscribe to the topics and authors of their interest. The editor‑in-chief of the new publication Kirill Martynov also writes weekly personal takes on recent Terrible News.

On March 6, 2022, Roskomnadzor blocked the website of the main publication of the Russian scientific community, Troitsky Variant‑Science, for publishing an anti‑war letter signed by more than 8,000 scientists‑one of the first statements by a professional community condemning the invasion. The T‑invariant project, edited by scientific journalist Olga Orlova, was relaunched in February 2023, focusing on science under the conditions of war in Ukraine.

The Bell project, created by a team of journalists who had departed leading Russian business publications Vedomosti and Forbes, launched the Telegram channel titled What do you get out of it?, which discusses how political economic news affect everyone on a personal level. Meduza also started a newsletter titled Signal, which explains the current developments instead of simply delivering facts, since “under the new conditions, the ability to understand news is not just useful, it is a vital skill.”

The St. Petersburg‑based Bumaga (Paper) created a newsletter titled Inhale. Exhale. Every evening, the publication recounts the events of the day, and then gives “one story about people that allows [readers] to look at the world with hope. It’s an exhale.“

“The Russia of the future, if it is meant to be, must be reassembled from below. If the reassembly begins again in Moscow, [the country] will most likely become the same as it is now: imperial, colonizing, a threat to its neighbors. Therefore, the assembly point of the new country should be in the regions: Siberia, Kuban, Bashkortostan, Tatarstan, the Urals…”

“The Russia of the future, if it is meant to be, must be reassembled from below. If the reassembly begins again in Moscow, [the country] will most likely become the same as it is now: imperial, colonizing, a threat to its neighbors. Therefore, the assembly point of the new country should be in the regions: Siberia, Kuban, Bashkortostan, Tatarstan, the Urals…”

This is how independent regional journalists from Russia announced their new project about the regions titled Says NeMoskva (some of them continue to work on the ground, others fled the country). The online publication covers issues of local identity and interests, possible institutions and tools for protecting these interests and coordinating efforts.

In May 2022, the New Tab was launched, another online publication featuring longreads about life in the regions. “It was literally a new tab that you can open and where you can read a dramatic story‑not from the battlefield, but about how people’s lives are changing at home,“ the authors explain.

Employees of some regional media faced issues of splitting the team: while leaders left the country due to persecution and settled to manage editorial offices remotely, correspondents continued to their job on the ground. “We have to protect our employees: hide their names, remove bylines, encrypt communication,” explains Ivan Rublev, editor‑in-chief of Yekaterinburg media It's My City.

Andrey Maslov, editor‑in-chief of the Belgorod publication Fonar.tv, offers another view:

This is how independent regional journalists from Russia announced their new project about the regions titled Says NeMoskva (some of them continue to work on the ground, others fled the country). The online publication covers issues of local identity and interests, possible institutions and tools for protecting these interests and coordinating efforts.

In May 2022, the New Tab was launched, another online publication featuring longreads about life in the regions. “It was literally a new tab that you can open and where you can read a dramatic story‑not from the battlefield, but about how people’s lives are changing at home,“ the authors explain.

Employees of some regional media faced issues of splitting the team: while leaders left the country due to persecution and settled to manage editorial offices remotely, correspondents continued to their job on the ground. “We have to protect our employees: hide their names, remove bylines, encrypt communication,” explains Ivan Rublev, editor‑in-chief of Yekaterinburg media It's My City.

Andrey Maslov, editor‑in-chief of the Belgorod publication Fonar.tv, offers another view:

“We haven’t left Russia: I may disagree with something, but I have an audience, and I believe that it is necessary to work here, otherwise the context is lost, you start thinking abstractly, not fully understanding how the audience perceives it. When you are away from the place you are writing about, it is harder to understand the pain.“

“We haven’t left Russia: I may disagree with something, but I have an audience, and I believe that it is necessary to work here, otherwise the context is lost, you start thinking abstractly, not fully understanding how the audience perceives it. When you are away from the place you are writing about, it is harder to understand the pain.“

“Journalists in Russia, I think, need to write about what ordinary people in Russia are worried about. As for the foreign policy situation, I think there are enough high‑quality and very good journalists who have left Russia and can write on these topics calmly,“ argues Vladislav Postnikov, editor‑in-chief of Vecherniye Vedomosti from Yekaterinburg.

“Journalists in Russia, I think, need to write about what ordinary people in Russia are worried about. As for the foreign policy situation, I think there are enough high‑quality and very good journalists who have left Russia and can write on these topics calmly,” argues Vladislav Postnikov, editor‑in-chief of Vecherniye Vedomosti from Yekaterinburg.

“It is important that new projects live for a long time, even if they are small,“ notes journalist and publisher Sergey Parkhomenko. “The duration of the effort and the ability to cooperate are important.”

Among such collective projects is the project titled “Who answered for the words”‑the result of the work of three teams: Tomsk TV2, St. Petersburg Paper, and the Editor‑22 project. This is a platform where editors and media owners, media lawyers and other legal professionals explain what happened to Russian regional journalism after February 24, 2022.

For the Russian audience, investigative media, such as Project, Important Stories, The Insider, Bellingcat, and Alexei Navalny’s team have launched a free mobile application Samizdat, which gives access to their texts without a VPN.

The latest impressive example of the collective efforts of independent media and their audience inside the country has been the June 12 marathon of solidarity with political prisoners and all Russians who oppose to war. In 12 hours, the participating publications managed to collect 34 million rubles ($400,000) in donations.

“It is important that new projects live for a long time, even if they are small,” notes journalist and publisher Sergey Parkhomenko. “The duration of the effort and the ability to cooperate are important.”

Among such collective projects is the project titled “Who answered for the words”‑the result of the work of three teams: Tomsk TV2, St. Petersburg Paper, and the Editor‑22 project. This is a platform where editors and media owners, media lawyers and other legal professionals explain what happened to Russian regional journalism after February 24, 2022.

For the Russian audience, investigative media, such as Project, Important Stories, The Insider, Bellingcat, and Alexei Navalny’s team have launched a free mobile application Samizdat, which gives access to their texts without a VPN.

The latest impressive example of the collective efforts of independent media and their audience inside the country has been the June 12 marathon of solidarity with political prisoners and all Russians who oppose to war. In 12 hours, the participating publications managed to collect 34 million rubles ($400,000) in donations.

“We are doing great at helping [civil society] organizations and media: they are effective, indestructible, recover even after a direct “nuclear strike,“ relentlessly self‑renew, and adapt to the needs of reality. And look with what energy and appreciation people use the opportunity to do something noble and at the same time effective,” commented political scientist Ekaterina Shulmann, who joined the marathon with her own YouTube channel. “That is, not to sacrifice yourself for symbolic purposes, but to take a risk in order to really help someone.“

“We are doing great at helping [civil society] organizations and media: they are effective, indestructible, recover even after a direct “nuclear strike,“ relentlessly self‑renew, and adapt to the needs of reality. And look with what energy and appreciation people use the opportunity to do something noble and at the same time effective,” commented political scientist Ekaterina Shulmann, who joined the marathon with her own YouTube channel. “That is, not to sacrifice yourself for symbolic purposes, but to take a risk in order to really help someone.“

Independent media themselves, new and old, also need help to stay in touch with readers and viewers. In June, Reporters Without Borders and independent Russian media appealed to the Big Tech companies, including Meta, Google, Twitter, etc., with a request to create a group “Engineers against Dictatorship” to prevent the shutdown of the Russian segment of the Internet: “As the [presidential] election time approaches, we have serious reasons to suspect that this fall, YouTube and Telegram may be completely blocked in Russia, which will turn more than 140 million people into hostages of the state propaganda apparatus.”

The initiative was supported by the Nobel Peace Prize laureate, editor‑in-chief of Novaya Gazeta Dmitry Muratov (“Now in Russia, the entire system of content delivery is under threat of destruction. Freedom of speech today is about technology,“ he noted) and was signed by 40 human rights activists and editors of Russian media, from Mediazona to Memorial. The European Federation of Journalists and the Association of Journalists of the Netherlands also joined the initiative.

February 24, 2022, put an end to the market of independent Russian media as we knew it. Almost all media that are not controlled by the Kremlin now are forced to work from abroad, their websites are blocked in Russia, while free journalism inside the country became dangerous.

Nevertheless, we observe the growth of a diverse group of independent media projects; new ones sprout in place of the liquidated ones, journalists react to the audience’s changing needs and continue to carry out their mission. This includes serving as a bridge between those who left Russia and those who stayed, working to ensure that Russian civil society not only does not split, but also expands.

Independent media themselves, new and old, also need help to stay in touch with readers and viewers. In June, Reporters Without Borders and independent Russian media appealed to the Big Tech companies, including Meta, Google, Twitter, etc., with a request to create a group “Engineers against Dictatorship” to prevent the shutdown of the Russian segment of the Internet: “As the [presidential] election time approaches, we have serious reasons to suspect that this fall, YouTube and Telegram may be completely blocked in Russia, which will turn more than 140 million people into hostages of the state propaganda apparatus.”

The initiative was supported by the Nobel Peace Prize laureate, editor‑in-chief of Novaya Gazeta Dmitry Muratov (“Now in Russia, the entire system of content delivery is under threat of destruction. Freedom of speech today is about technology,” he noted) and was signed by 40 human rights activists and editors of Russian media, from Mediazona to Memorial. The European Federation of Journalists and the Association of Journalists of the Netherlands also joined the initiative.

February 24, 2022, put an end to the market of independent Russian media as we knew it. Almost all media that are not controlled by the Kremlin now are forced to work from abroad, their websites are blocked in Russia, while free journalism inside the country became dangerous.

Nevertheless, we observe the growth of a diverse group of independent media projects; new ones sprout in place of the liquidated ones, journalists react to the audience’s changing needs and continue to carry out their mission. This includes serving as a bridge between those who left Russia and those who stayed, working to ensure that Russian civil society not only does not split, but also expands.

No one in Russia wants a long‑term war, and the mobilization for the war is unpopular

By Vladimir Milov

December 30, 2022

Article

Article By Vadim Shtepa

December 19, 2022

Article

Article Why the World Must Support Russians Fleeing Mobilization

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

October 03, 2022

No one in Russia wants a long‑term war, and the mobilization for the war is unpopular

By Vladimir Milov

December 30, 2022

Article

Article By Vadim Shtepa

December 19, 2022

Article

Article Why the World Must Support Russians Fleeing Mobilization

By Fedor Krasheninnikov

October 03, 2022