Public Opinion in Russia and War in Ukraine: End of the Year Recap

No one in Russia wants a long‑term war, and the mobilization for the war is unpopular

By Vladimir Milov December 30, 2022

No one in Russia wants a long‑term war, and the mobilization for the war is unpopular

By Vladimir Milov December 30, 2022

For several months now, FRF has been analyzing the shifts in Russian public opinion on the war. The key insights are as follows:

For several months now, FRF has been analyzing the shifts in Russian public opinion on the war. The key insights are as follows:

These interpretations are largely confirmed by the latest polling data. In the recent published Levada Center poll on the war against Ukraine, unconditional support for the war (“definitely support”) has dropped to an all‑time low of 41%, against all‑time high of 52% recorded in March.

Bundled up with conditional support (“more support than oppose”) it does add up to over 70% of the society, which is a number that the Western media is frequently citing. But doing so is a mistake, as those two numbers are not a contingent of one another, as conditional support often goes with a lot of reservations and concerns.

If one looks into more detailed data like focus groups, it becomes clear that “more support the war than oppose” is largely signaling of minimal allegiance to the authorities, rather than the actual backing of the military action against Ukraine.

As noted above, about 10–15% of the Russians that are opposed to the war are afraid to admit it to pollsters — this had been revealed through differential between anonymous street polls and phone polls, as well as field experiments posing indirect questions (as was explained here). Once that factor is taken into account, the actual solid unconditional support for the war falls confidently below 40%.

According to various available indirect data (like focus groups), that is the actual honest assessment of the number of people consciously supporting the war — within 30–40% range. That is far below the “majority” which is widely discussed — but still an appallingly high number.

However, is this number proving that Russians are an aggressive imperialist nation, driven by post‑imperial nostalgia and seeking conquest of other countries? Facts on the ground cast doubt on that assertion.

Prior to the war, there was never any bottom‑up demand from Russians for conquest of Ukraine, and Russians in their views have simply gone along with state propaganda.

Polls show that Putin’s aggression against Ukraine came as much a surprise for the Russians as for anyone else. According to pre‑war Levada poll published in February, only 5% of Russians thought that war with Ukraine was “inevitable”; plurality (49%) believed that the war wouldn’t happen, and that war rumors are largely a 'provocation' by the West (very much in line with official propaganda at the time, which had flatly denied that Russia was planning an invasion of Ukraine). 51% of Russians in that pre‑war February poll said that they were “frightened” by the prospect of a war with Ukraine; there was clearly no upbeat ultra‑patriotic enthusiasm about that.

When Russians are being asked about causes of the war, they mostly cite defensive, not offensive reasons to justify the invasion. Only a limited number of people (about 20% of war supporters, fewer than 10% of Russians overall — not a unique number of aggressive members of society, even by the standards of developed democracies) says that Ukraine should not exist as a nation and the goal should be to incorporate Ukraine into Russia (as explained here).

Most of those who express support for the war repeat the following propaganda lines:

These interpretations are largely confirmed by the latest polling data. In the recent published Levada Center poll on the war against Ukraine, unconditional support for the war (“definitely support”) has dropped to an all‑time low of 41%, against all‑time high of 52% recorded in March.

Bundled up with conditional support (“more support than oppose”) it does add up to over 70% of the society, which is a number that the Western media is frequently citing. But doing so is a mistake, as those two numbers are not a contingent of one another, as conditional support often goes with a lot of reservations and concerns.

If one looks into more detailed data like focus groups, it becomes clear that “more support the war than oppose” is largely signaling of minimal allegiance to the authorities, rather than the actual backing of the military action against Ukraine.

As noted above, about 10–15% of the Russians that are opposed to the war are afraid to admit it to pollsters — this had been revealed through differential between anonymous street polls and phone polls, as well as field experiments posing indirect questions (as was explained here). Once that factor is taken into account, the actual solid unconditional support for the war falls confidently below 40%.

According to various available indirect data (like focus groups), that is the actual honest assessment of the number of people consciously supporting the war — within 30–40% range. That is far below the “majority” which is widely discussed — but still an appallingly high number.

However, is this number proving that Russians are an aggressive imperialist nation, driven by post‑imperial nostalgia and seeking conquest of other countries? Facts on the ground cast doubt on that assertion.

Prior to the war, there was never any bottom‑up demand from Russians for conquest of Ukraine, and Russians in their views have simply gone along with state propaganda.

Polls show that Putin’s aggression against Ukraine came as much a surprise for the Russians as for anyone else. According to pre‑war Levada poll published in February, only 5% of Russians thought that war with Ukraine was “inevitable”; plurality (49%) believed that the war wouldn’t happen, and that war rumors are largely a 'provocation' by the West (very much in line with official propaganda at the time, which had flatly denied that Russia was planning an invasion of Ukraine). 51% of Russians in that pre‑war February poll said that they were “frightened” by the prospect of a war with Ukraine; there was clearly no upbeat ultra‑patriotic enthusiasm about that.

When Russians are being asked about causes of the war, they mostly cite defensive, not offensive reasons to justify the invasion. Only a limited number of people (about 20% of war supporters, fewer than 10% of Russians overall — not a unique number of aggressive members of society, even by the standards of developed democracies) says that Ukraine should not exist as a nation and the goal should be to incorporate Ukraine into Russia (as explained here).

Most of those who express support for the war repeat the following propaganda lines:

Without question, Russian propaganda has been very effective in promoting false narratives, and efforts should be increased to counter them. Many Russians deeply believe in these narratives, which have been promoted for nearly a decade.

There is a popular “sorting question”, “where have you been for 8 years?”, which implies that, according to Russian propaganda, Ukraine has been shelling Russian‑speaking people in Donbas for 8 years and that Russia only intervened “to save them” after its patience worn out. Debunking a long‑promoted propaganda narrative is not easy, but it can be effective.

Another important propaganda narrative that helps create support for Putin’s actions is the idea that “everyone else is doing it, so why can’t we?” This narrative suggests that other countries are also engaging in questionable or nefarious actions, so it is justified for Russia to do the same.

People in the West, shocked by the atrocities committed by Russians in Bucha, Irpin, Izyum, and the barbaric bombardments of Ukrainian cities and towns, are bewildered by the insensitivity of Russians to these tragedies. However, if you are an ordinary Russian living your daily life and watching Russian TV, you reside in a completely different information space.

For years, Kremlin‑controlled media has taken every opportunity to brainwash Russians with coverage of Western bombardments of places like Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Afghanistan. The NATO bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999 remains a particularly strong trigger used by the Russian propaganda. Of course, Russian narratives about these military operations are biased and distorted.

But how could ordinary Russians know this? They have been desensitized with the footage of Western military interventions in other countries, with an emphasis on civilian casualties, destruction, and other negative consequences, for decades.

So, unfortunately, many Russians, after all these years of propaganda, treat war and aggression as some sort of “new normal”. “America is doing that all the time in its interests — why can’t we?” In the view of many Russians brainwashed by propaganda, Russia had simply chosen to defend its interests “in the same way that America has been doing for years”.

Of course, this type of whataboutism is deeply flawed, but it offers a straightforward way for “friend or foe” sorting during wartime. Putin himself frequently references Western military operations in Iraq and other countries, drawing incorrect parallels that are quickly internalized by ordinary Russians.

These individuals may lack sufficient knowledge and simply be motivated by tribalistic instincts of the “it’s my country, through thick and thin” type. They may even dislike what their country is doing but have a deeply skeptical view of the West due to its past wars and bombardments.

Those in the West who depict Russians as an aggressive, imperialistic nation should keep in mind that many Russians genuinely believe that what Russia is doing in Ukraine is no different than what America has been doing in previous decades. They often view the universal condemnation of Russia’s actions as a sign of “hypocritic Russophobia” in the West, rather than a sign that their own country is engaged in something terribly wrong.

It is important to remember that inside Russia, information about atrocities and war crimes in Ukraine is heavily censored, and the awareness of the Russian public about these crimes is low. Shortly after the start of the war, Russian authorities introduced new amendments to the Criminal Code that included punishment for “spreading fake information about the actions of the Russian military” (i.e., telling the truth about the war) with up to 15 years in prison.

Practice shows that courts do not acquit those charged under this new article of the Criminal Code; 100% of those charged are convicted. Early sentences are particularly harsh: politicians Ilya Yashin and Alexey Gorinov were sentenced to 8.5 and 7 years in prison, respectively, and activist Altan Ochirov from Kalmykia was sentenced to 5 years.

Russian propaganda insists that Russia’s military “only bombs military targets and carefully avoids civilian casualties”; however, evidence to the contrary is heavily censored, and there is a highly effective media machine that portrays reports of civilian casualties and military atrocities as “fake news” (such as the infamous “corpse moving its hand” attack against the video of the aftermath of the Bucha massacre).

Despite this, brave Russians continue to spread the truth about Russia’s aggression and war crimes in Ukraine. Unfortunately, many counter‑propaganda efforts are quite ineffective and even counterproductive.

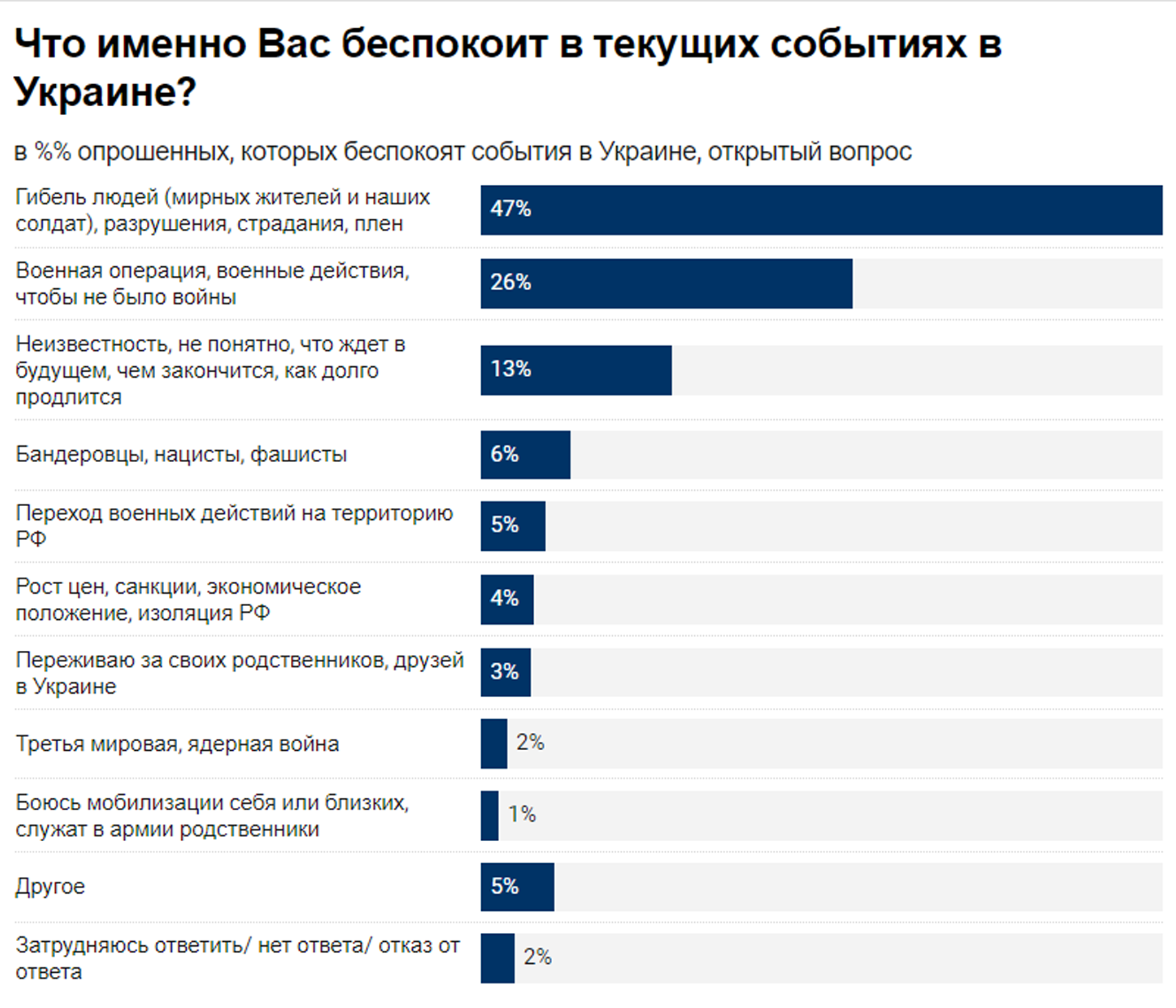

However, when information about atrocities by the Russian military does manage to get through in credible formats it becomes an eye‑opener, and many Russians do change their minds. When, in recent months, the Levada Center asked detailed questions about what concerns Russians most regarding the war, 47% said that human suffering and deaths were the most concerning factor, while only 6% cited “the presence of fascists and Banderites” in Ukraine (a dominant narrative promoted by the Kremlin).

Without question, Russian propaganda has been very effective in promoting false narratives, and efforts should be increased to counter them. Many Russians deeply believe in these narratives, which have been promoted for nearly a decade.

There is a popular “sorting question”, “where have you been for 8 years?”, which implies that, according to Russian propaganda, Ukraine has been shelling Russian‑speaking people in Donbas for 8 years and that Russia only intervened “to save them” after its patience worn out. Debunking a long‑promoted propaganda narrative is not easy, but it can be effective.

Another important propaganda narrative that helps create support for Putin’s actions is the idea that “everyone else is doing it, so why can’t we?” This narrative suggests that other countries are also engaging in questionable or nefarious actions, so it is justified for Russia to do the same.

People in the West, shocked by the atrocities committed by Russians in Bucha, Irpin, Izyum, and the barbaric bombardments of Ukrainian cities and towns, are bewildered by the insensitivity of Russians to these tragedies. However, if you are an ordinary Russian living your daily life and watching Russian TV, you reside in a completely different information space.

For years, Kremlin‑controlled media has taken every opportunity to brainwash Russians with coverage of Western bombardments of places like Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Afghanistan. The NATO bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999 remains a particularly strong trigger used by the Russian propaganda. Of course, Russian narratives about these military operations are biased and distorted.

But how could ordinary Russians know this? They have been desensitized with the footage of Western military interventions in other countries, with an emphasis on civilian casualties, destruction, and other negative consequences, for decades.

So, unfortunately, many Russians, after all these years of propaganda, treat war and aggression as some sort of “new normal”. “America is doing that all the time in its interests — why can’t we?” In the view of many Russians brainwashed by propaganda, Russia had simply chosen to defend its interests “in the same way that America has been doing for years”.

Of course, this type of whataboutism is deeply flawed, but it offers a straightforward way for “friend or foe” sorting during wartime. Putin himself frequently references Western military operations in Iraq and other countries, drawing incorrect parallels that are quickly internalized by ordinary Russians.

These individuals may lack sufficient knowledge and simply be motivated by tribalistic instincts of the “it’s my country, through thick and thin” type. They may even dislike what their country is doing but have a deeply skeptical view of the West due to its past wars and bombardments.

Those in the West who depict Russians as an aggressive, imperialistic nation should keep in mind that many Russians genuinely believe that what Russia is doing in Ukraine is no different than what America has been doing in previous decades. They often view the universal condemnation of Russia’s actions as a sign of “hypocritic Russophobia” in the West, rather than a sign that their own country is engaged in something terribly wrong.

It is important to remember that inside Russia, information about atrocities and war crimes in Ukraine is heavily censored, and the awareness of the Russian public about these crimes is low. Shortly after the start of the war, Russian authorities introduced new amendments to the Criminal Code that included punishment for “spreading fake information about the actions of the Russian military” (i.e., telling the truth about the war) with up to 15 years in prison.

Practice shows that courts do not acquit those charged under this new article of the Criminal Code; 100% of those charged are convicted. Early sentences are particularly harsh: politicians Ilya Yashin and Alexey Gorinov were sentenced to 8.5 and 7 years in prison, respectively, and activist Altan Ochirov from Kalmykia was sentenced to 5 years.

Russian propaganda insists that Russia’s military “only bombs military targets and carefully avoids civilian casualties”; however, evidence to the contrary is heavily censored, and there is a highly effective media machine that portrays reports of civilian casualties and military atrocities as “fake news” (such as the infamous “corpse moving its hand” attack against the video of the aftermath of the Bucha massacre).

Despite this, brave Russians continue to spread the truth about Russia’s aggression and war crimes in Ukraine. Unfortunately, many counter‑propaganda efforts are quite ineffective and even counterproductive.

However, when information about atrocities by the Russian military does manage to get through in credible formats it becomes an eye‑opener, and many Russians do change their minds. When, in recent months, the Levada Center asked detailed questions about what concerns Russians most regarding the war, 47% said that human suffering and deaths were the most concerning factor, while only 6% cited “the presence of fascists and Banderites” in Ukraine (a dominant narrative promoted by the Kremlin).

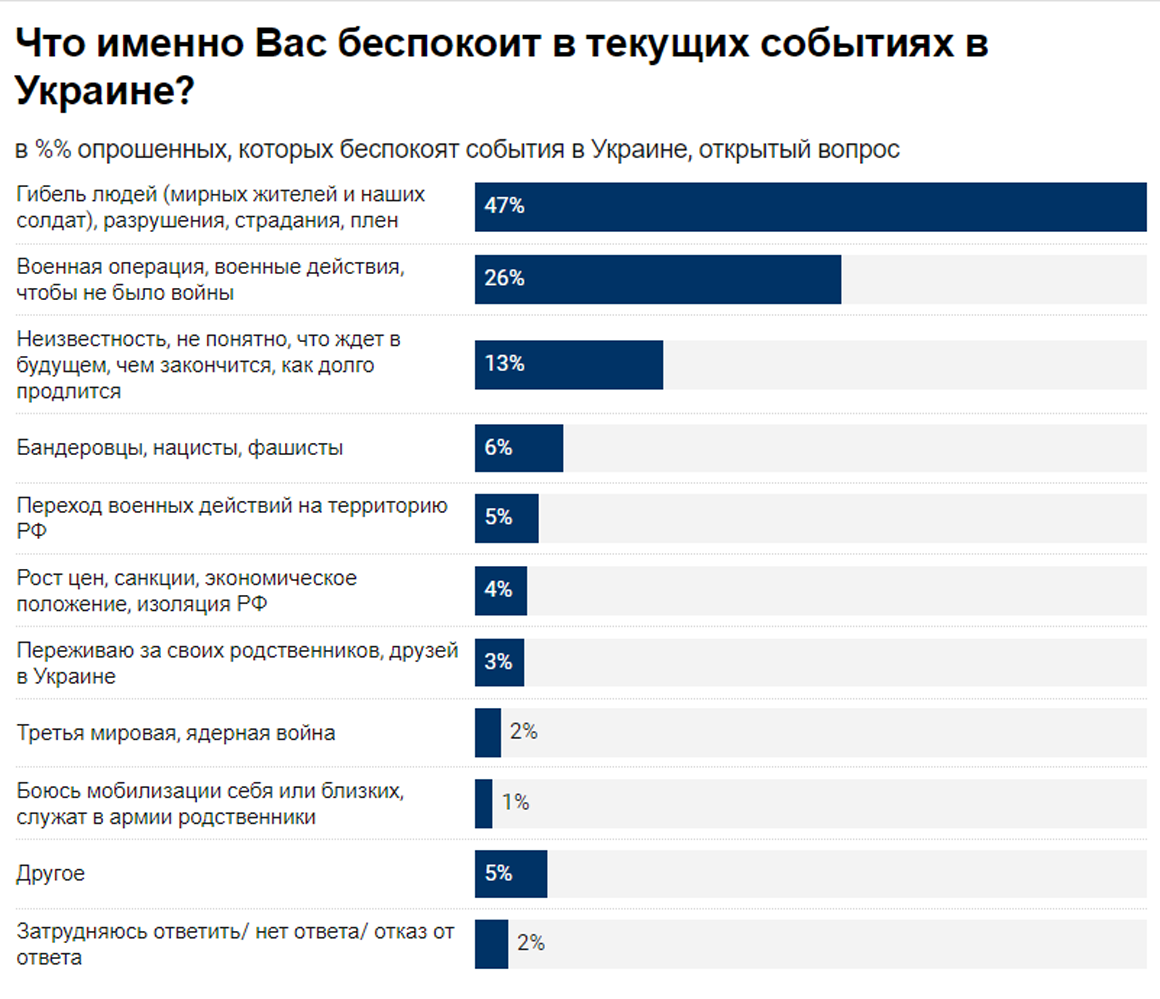

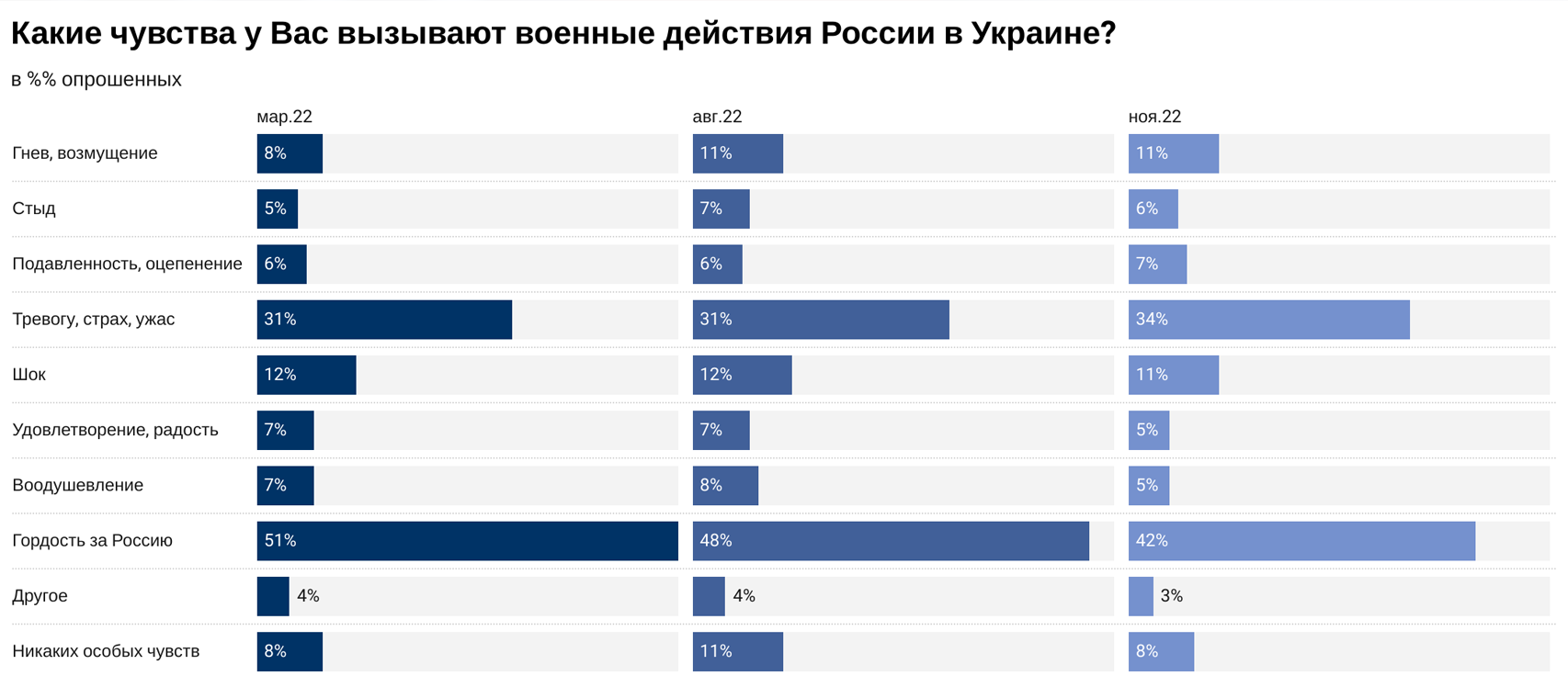

Negative sentiments about their lives in general, and about the war specifically, as well as a sharp decline in trust for state media also suggest that Russians are not happy about the actions of their military in Ukraine and the state propaganda. According to Kremlin‑linked pollster FOM, in the fall of 2022, Russians were more likely to be in an “anxious mood” than “calm” (54% vs. 38% by the end of December).

When asked about their emotions regarding the war, only 42% (a number consistent with the measurement of solid unconditional support for the war) say that they feel “pride for Russia”.

That is followed by 34% who say that they feel “anxiety, fear, horror”; 11% feel “anger, outrage, shock”; 7% feel “depression, numbness”; and 6% feel “shock.“ “Satisfaction, joy, excitement” about the war are felt by 5% of respondents.

Another indirect sign that support for the war is much lower than claimed is the plunging ratings of state propaganda channels. This development has been reported by various pollsters throughout the year, including advertiser GroupM, Levada, and Romir. According to Romir (which itself is quite loyal to the authorities), there has been a significant drop in the audience of main state television channels since the beginning of the war.

Channel One’s audience share fell from 33.7% in February to 25.5% in July; the share of Russia 1 fell from 30.9% to 23%; and the NTV channel’s share fell from 21.1% to 16.6%. These figures have remained more or less stable since then. According to the Levada Center, by the end of 2022, trust in state television had dropped to 49%, near all‑time lows.

Earlier in the year, the GroupM advertising company reported a drop in trust in state‑run television channels from 33% to 23% after the beginning of the war.

Negative sentiments about their lives in general, and about the war specifically, as well as a sharp decline in trust for state media also suggest that Russians are not happy about the actions of their military in Ukraine and the state propaganda. According to Kremlin‑linked pollster FOM, in the fall of 2022, Russians were more likely to be in an “anxious mood” than “calm” (54% vs. 38% by the end of December).

When asked about their emotions regarding the war, only 42% (a number consistent with the measurement of solid unconditional support for the war) say that they feel “pride for Russia”.

That is followed by 34% who say that they feel “anxiety, fear, horror”; 11% feel “anger, outrage, shock”; 7% feel “depression, numbness”; and 6% feel “shock.” “Satisfaction, joy, excitement” about the war are felt by 5% of respondents.

Another indirect sign that support for the war is much lower than claimed is the plunging ratings of state propaganda channels. This development has been reported by various pollsters throughout the year, including advertiser GroupM, Levada, and Romir. According to Romir (which itself is quite loyal to the authorities), there has been a significant drop in the audience of main state television channels since the beginning of the war.

Channel One’s audience share fell from 33.7% in February to 25.5% in July; the share of Russia 1 fell from 30.9% to 23%; and the NTV channel’s share fell from 21.1% to 16.6%. These figures have remained more or less stable since then. According to the Levada Center, by the end of 2022, trust in state television had dropped to 49%, near all‑time lows.

Earlier in the year, the GroupM advertising company reported a drop in trust in state‑run television channels from 33% to 23% after the beginning of the war.

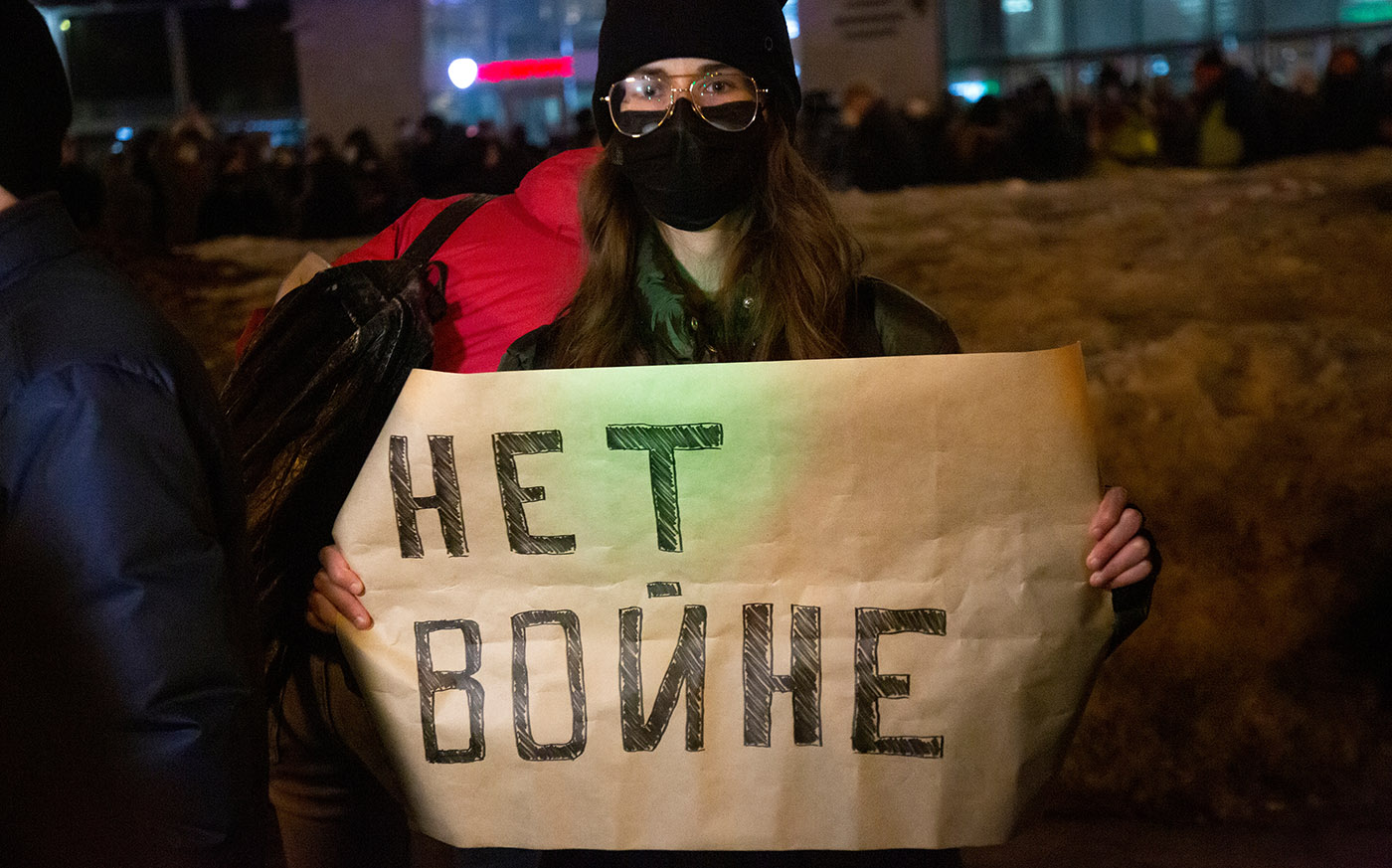

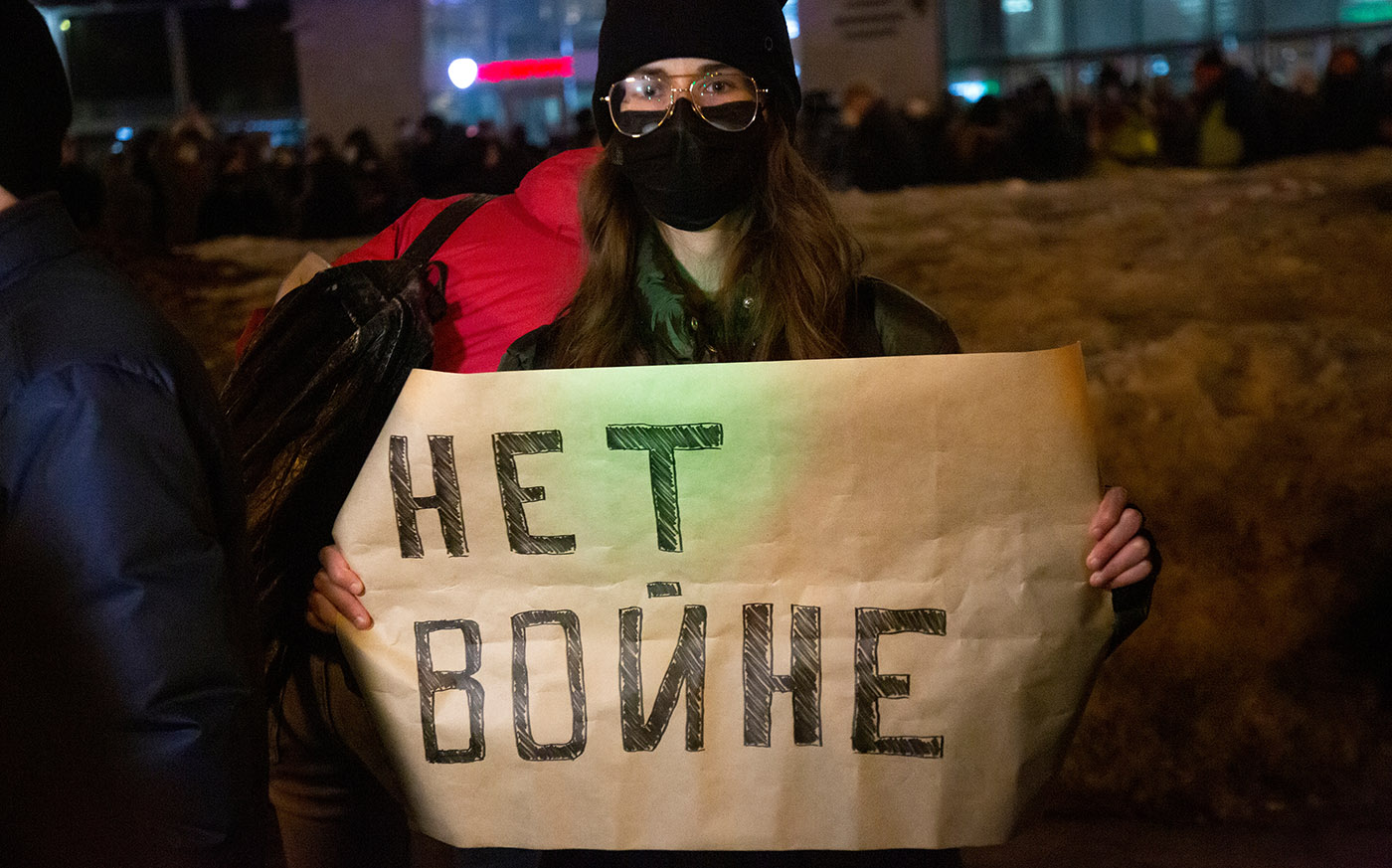

Another source of hope emerging from the polls is a solid anti‑war minority in Russia. According to Levada polls, currently 21% of Russians dare to openly say that they are against the war — a brave enough act given the potential consequences. Keeping in mind the percentage of those who may oppose the war but are afraid to say it, it is likely that over 30% of the population is consciously against the war.

These are not marginal numbers; this is a sizable part of Russian society. Another telling number is that provided by independent human rights NGO OVD‑Info, according to which about 20,000 Russians have been detained at anti‑war protests since the war broke out on February 24, 2022. This is a verifiable, trusted number based on a careful count of individual detention cases.

The OVD‑Info statistics uphold stringent standards and therefore tend to underreport. Moreover, the number of detentions at protests is usually significantly lower than the number of participants, as only a fraction of protesters are arrested immediately (though most do face a persecution in following months).

This means that the overall number of Russians protesting the war since February 24 is likely in the six digits. This is a very sizable number, considering the significantly elevated risks and real prison terms for speaking out against the war.

There is a misconception that Russians are not protesting the war. This is fueled by the expectation of highly visible protests like those that occurred during the Anti‑War Marches of 2014–2015 and the Navalny era rallies of 2017–2021.

However, these types of protests are no longer possible because opposition rallies in Russia have been criminalized and opposition groups have been dismantled, with their leaders either arrested or exiled. The government is also reducing the public visibility of protests by surrounding main city squares with fences, forcing protesters to disperse on nearby side streets.

Moreover, oppressive policies against journalists and independent media outlets have led to many being shut down or exiled, even before the start of the war. Since the war started, reporting on anti‑war protests has been classified as a criminal offense of “spreading fake news about the special military operation,“ significantly reducing the ability of journalists to report on the scale of protests. Many social media platforms have also been shut down, further diminishing the reporting on protests.

As a result, anti‑war protests in 2022 have been less visible to the international community compared to protest rallies in previous years. However, a careful examination of cross‑regional news on protests reveals that the number of people on the streets was significant.

In the absence of organized opposition on the streets, and with the increased police brutality and criminalization of anti‑war protests, they quickly faded as people saw no point in getting arrested.

According to our feedback from across the country, society is currently in a regrouping phase, adapting to the new repressive reality, and we can expect to see more protest activity in the future. Therefore, it is deeply unfair to blame Russians for “not protesting the war.”

The shifting public opinion can serve as a driving force behind the mobilization of masses and the fueling of protests. Throughout 2022, we have observed a trend of steadily declining support for Putin’s war, but there is still room for improvement. What can be done to accelerate this shift in Russian public opinion?

Data suggests that certain approaches of counter‑propaganda campaigns are not effective and may even be counterproductive. One example is projects that involve phone calls to ordinary Russians to discuss the war. The authors of such initiatives likely envisioned that this direct, person‑to-person communication would be effective in breaking through the wall of state propaganda. However, several realities of the actual Russian situation are underestimated:

Another source of hope emerging from the polls is a solid anti‑war minority in Russia. According to Levada polls, currently 21% of Russians dare to openly say that they are against the war — a brave enough act given the potential consequences. Keeping in mind the percentage of those who may oppose the war but are afraid to say it, it is likely that over 30% of the population is consciously against the war.

These are not marginal numbers; this is a sizable part of Russian society. Another telling number is that provided by independent human rights NGO OVD‑Info, according to which about 20,000 Russians have been detained at anti‑war protests since the war broke out on February 24, 2022. This is a verifiable, trusted number based on a careful count of individual detention cases.

The OVD‑Info statistics uphold stringent standards and therefore tend to underreport. Moreover, the number of detentions at protests is usually significantly lower than the number of participants, as only a fraction of protesters are arrested immediately (though most do face a persecution in following months).

This means that the overall number of Russians protesting the war since February 24 is likely in the six digits. This is a very sizable number, considering the significantly elevated risks and real prison terms for speaking out against the war.

There is a misconception that Russians are not protesting the war. This is fueled by the expectation of highly visible protests like those that occurred during the Anti‑War Marches of 2014–2015 and the Navalny era rallies of 2017–2021.

However, these types of protests are no longer possible because opposition rallies in Russia have been criminalized and opposition groups have been dismantled, with their leaders either arrested or exiled. The government is also reducing the public visibility of protests by surrounding main city squares with fences, forcing protesters to disperse on nearby side streets.

Moreover, oppressive policies against journalists and independent media outlets have led to many being shut down or exiled, even before the start of the war. Since the war started, reporting on anti‑war protests has been classified as a criminal offense of “spreading fake news about the special military operation,” significantly reducing the ability of journalists to report on the scale of protests. Many social media platforms have also been shut down, further diminishing the reporting on protests.

As a result, anti‑war protests in 2022 have been less visible to the international community compared to protest rallies in previous years. However, a careful examination of cross‑regional news on protests reveals that the number of people on the streets was significant.

In the absence of organized opposition on the streets, and with the increased police brutality and criminalization of anti‑war protests, they quickly faded as people saw no point in getting arrested.

According to our feedback from across the country, society is currently in a regrouping phase, adapting to the new repressive reality, and we can expect to see more protest activity in the future. Therefore, it is deeply unfair to blame Russians for “not protesting the war.”

The shifting public opinion can serve as a driving force behind the mobilization of masses and the fueling of protests. Throughout 2022, we have observed a trend of steadily declining support for Putin’s war, but there is still room for improvement. What can be done to accelerate this shift in Russian public opinion?

Data suggests that certain approaches of counter‑propaganda campaigns are not effective and may even be counterproductive. One example is projects that involve phone calls to ordinary Russians to discuss the war. The authors of such initiatives likely envisioned that this direct, person‑to-person communication would be effective in breaking through the wall of state propaganda. However, several realities of the actual Russian situation are underestimated:

The belief that all Russians are narrow‑minded people who just need to be lectured on basic things is deeply misguided. The reality is different: Russians are victims of sophisticated, professional propaganda that is based on a deep understanding of Russian psychology and worldview.

Emotions and lightweight approaches don’t work here; a professional approach is needed, with a native level understanding of sensibilities, sentiments, and the information environment.

Foreign narratives like “Russia should be broken apart into separate territories” are especially counterproductive. Many of these narratives, contrary to the intentions of their authors, strengthen the Kremlin’s propaganda rather than disproving it (“we told you — their real intent is to destroy Russia “; “you see, the West has no concern about your well‑being”).

The belief that all Russians are narrow‑minded people who just need to be lectured on basic things is deeply misguided. The reality is different: Russians are victims of sophisticated, professional propaganda that is based on a deep understanding of Russian psychology and worldview.

Emotions and lightweight approaches don’t work here; a professional approach is needed, with a native level understanding of sensibilities, sentiments, and the information environment.

Foreign narratives like “Russia should be broken apart into separate territories” are especially counterproductive. Many of these narratives, contrary to the intentions of their authors, strengthen the Kremlin’s propaganda rather than disproving it (“we told you — their real intent is to destroy Russia “; “you see, the West has no concern about your well‑being”).

On the other hand, Russian opposition activists and independent journalists have made significant progress in changing the propaganda‑distorted worldview of the Russian people. Independent broadcasting through social media channels has reached an unprecedented high in 2022, while trust and viewership of state media have declined.

According to Forbes Russia, YouTube’s average daily outreach in Russia increased from around 45 million in February to closer to 50 million by the second half of the year. Telegram’s average daily outreach also grew from around 25 million at the beginning of the war to over 40 million.

The most successful independent media outlets have proven to be visible alternatives to state‑run propaganda. Major Russian independent media channel TV Rain has nearly 4 million subscribers on YouTube after reopening in July 2022 (it was forced to shut down and relocate from Russia since March).

YouTube channels linked to Alexey Navalny’s team are also thriving: Navalny Live has crossed the 3 million subscriber threshold, and the newly‑launched channel Popular Politics went from just over 400,000 subscribers to 1.7 million by the end of the year. There is growing public interest in independent investigative journalism and relevant media outlets and YouTube channels, such as Proekt, Important Stories, and The Insider.

The combined regular audience of the independent and opposition Youtube channels in Russia is reaching as high as 30–40 million. Putin turned out to be afraid to block Youtube in Russia because of its widespread popularity among ordinary Russians, and the absence of comparable convenient and demanded platform.

Russian independent social media broadcasting has had a significant impact on shifting public opinion about the war in Ukraine and decreasing support for Putin’s war. These outlets deserve support, but it has become difficult for them to sustain themselves due to restrictions on cross‑border financial transactions and the departure of Visa and Mastercard from Russia. Most of their audiences and donors are still located in Russia.

Supporting independent anti‑Putin and anti‑war Russian broadcasting is worthwhile. Major broadcasting outlets and personalities have built a reputation with the Russian audience over the years.

It is important that the current independent broadcasting is done by Russians, for Russians, as this significantly increases its credibility. Putin’s aggression against Ukraine has set in motion a myriad of destructive processes whose toll will continue to grow.

On the other hand, Russian opposition activists and independent journalists have made significant progress in changing the propaganda‑distorted worldview of the Russian people. Independent broadcasting through social media channels has reached an unprecedented high in 2022, while trust and viewership of state media have declined.

According to Forbes Russia, YouTube’s average daily outreach in Russia increased from around 45 million in February to closer to 50 million by the second half of the year. Telegram’s average daily outreach also grew from around 25 million at the beginning of the war to over 40 million.

The most successful independent media outlets have proven to be visible alternatives to state‑run propaganda. Major Russian independent media channel TV Rain has nearly 4 million subscribers on YouTube after reopening in July 2022 (it was forced to shut down and relocate from Russia since March).

YouTube channels linked to Alexey Navalny’s team are also thriving: Navalny Live has crossed the 3 million subscriber threshold, and the newly‑launched channel Popular Politics went from just over 400,000 subscribers to 1.7 million by the end of the year. There is growing public interest in independent investigative journalism and relevant media outlets and YouTube channels, such as Proekt, Important Stories, and The Insider.

The combined regular audience of the independent and opposition Youtube channels in Russia is reaching as high as 30–40 million. Putin turned out to be afraid to block Youtube in Russia because of its widespread popularity among ordinary Russians, and the absence of comparable convenient and demanded platform.

Russian independent social media broadcasting has had a significant impact on shifting public opinion about the war in Ukraine and decreasing support for Putin’s war. These outlets deserve support, but it has become difficult for them to sustain themselves due to restrictions on cross‑border financial transactions and the departure of Visa and Mastercard from Russia. Most of their audiences and donors are still located in Russia.

Supporting independent anti‑Putin and anti‑war Russian broadcasting is worthwhile. Major broadcasting outlets and personalities have built a reputation with the Russian audience over the years.

It is important that the current independent broadcasting is done by Russians, for Russians, as this significantly increases its credibility. Putin’s aggression against Ukraine has set in motion a myriad of destructive processes whose toll will continue to grow.

The economic forecast for 2023 looks grim, and Russians' well‑being has steadily decreased since the invasion of Ukraine in 2014. We can expect a more receptive audience for efforts to further turn public opinion against Putin and continue the trend that emerged in 2022.

Supporting this trend is important, and the most effective way to do so is by supporting independent media and activist outlets that have already demonstrated success and growth.

The economic forecast for 2023 looks grim, and Russians' well‑being has steadily decreased since the invasion of Ukraine in 2014. We can expect a more receptive audience for efforts to further turn public opinion against Putin and continue the trend that emerged in 2022.

Supporting this trend is important, and the most effective way to do so is by supporting independent media and activist outlets that have already demonstrated success and growth.

By Vadim Shtepa

December 19, 2022

Article

Article What are the trends in Russian public opinion regarding the war and support for the Putin regime?

By Vladimir Milov

December 11, 2023

Article

Article By Free Russia Foundation

June 21, 2023

By Vadim Shtepa

December 19, 2022

Article

Article What are the trends in Russian public opinion regarding the war and support for the Putin regime?

By Vladimir Milov

December 11, 2023

Article

Article By Free Russia Foundation

June 21, 2023