The Transition Project: Restoration of Basic Freedoms

What should be done to reconstruct rights and freedoms?

By Olga Khvostunova May 29, 2024

What should be done to reconstruct rights and freedoms?

By Olga Khvostunova May 29, 2024

The organizers of the upcoming transformations will have a much easier task than their predecessors of the 1990s. Public consciousness is already «infected with the democratic virus»: Russians have embraced the ideals of democracy and the rule of law, so there will be no need to impose unfamiliar or alien values. Secondly, the scale of the upcoming changes is incomparable: in the 1990s, the transition involved not only moving from authoritarianism to democracy but also from socialism to capitalism. No such unpopular measures as mass privatization are anticipated. However, the main danger facing the transition will be the issue of redistributing powers between the central government and the regions, compounded by the problem of interethnic relations. It was precisely on this issue that the reformers of the Soviet era stumbled.

By 2022, the Russian Federation has signed and ratified dozens of international human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the European Convention on the Protection of Human Rights, and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Yet, over the last two decades, Russian authorities’ implementation of many of these treaties’ provisions has been at best flawed and at worst, they were willfully ignored or grossly violated.

In the last five years, abuses against basic rights and freedoms in violation of the country’s own Constitution have grown exponentially. In 2018, Russia emerged as the leading country in terms of the number of complaints filed to the European Court of Human Rights. The ECtHR has often found Russia guilty of violating the following articles of the European Convention on Human Rights:

By 2022, the Russian Federation has signed and ratified dozens of international human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the European Convention on the Protection of Human Rights, and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Yet, over the last two decades, Russian authorities’ implementation of many of these treaties’ provisions has been at best flawed and at worst, they were willfully ignored or grossly violated.

In the last five years, abuses against basic rights and freedoms in violation of the country’s own Constitution have grown exponentially. In 2018, Russia emerged as the leading country in terms of the number of complaints filed to the European Court of Human Rights. The ECtHR has often found Russia guilty of violating the following articles of the European Convention on Human Rights:

Russia under Vladimir Putin has emerged as one of the most egregious human rights abusers in recent years, even though its constitution, undermined as it was by the 2020 amendments, still provides for ample protection for basic human rights. The key problem is that this protection has increasingly become a declaration on paper in the absence of real, working implementation and watchdog mechanisms. The key problem is the consolidation of all political power in the hands of the president and the lack of independent legislative and judiciary. Two related problems are the silenced independent media and intimidated civil society. Finally, the history of rights protection in Russia shows that, with a few exceptions, the public never fought for their rights, especially for political rights and civil liberties. They were often simply handed down to it from above.

Based on the recent opinion polls, Russians value personal freedoms the most alongside rights to social security — the attitudes that are likely the result of the Soviet system structure, which was, to an extent, inherited by the current regime (see Table). Rights to participation in social and political life as well as freedom of assembly are at the bottom of the list. Yet, it is noteworthy that the right to fair trial and freedom of speech are at the top, with the value for the latter showing significant progress. In 2017, only 34 percent of the respondents said that freedom of speech was most important; in 2021, 61 percent who said so. These are also the two rights that the respondents noted as most often violated in 2021.

Going forward, democratic reformers will need to reckon with these problems to make sure that rights and freedoms are not simply handed down from above again, but upon securing genuine separation of powers, they should actively engage independent media and civil society organizations to educate the public about their rights and serve as watchdogs and exert pressure on authorities to enforce adherence to and protection of these rights.

Russia under Vladimir Putin has emerged as one of the most egregious human rights abusers in recent years, even though its constitution, undermined as it was by the 2020 amendments, still provides for ample protection for basic human rights. The key problem is that this protection has increasingly become a declaration on paper in the absence of real, working implementation and watchdog mechanisms. The key problem is the consolidation of all political power in the hands of the president and the lack of independent legislative and judiciary. Two related problems are the silenced independent media and intimidated civil society. Finally, the history of rights protection in Russia shows that, with a few exceptions, the public never fought for their rights, especially for political rights and civil liberties. They were often simply handed down to it from above.

Based on the recent opinion polls, Russians value personal freedoms the most alongside rights to social security — the attitudes that are likely the result of the Soviet system structure, which was, to an extent, inherited by the current regime (see Table). Rights to participation in social and political life as well as freedom of assembly are at the bottom of the list. Yet, it is noteworthy that the right to fair trial and freedom of speech are at the top, with the value for the latter showing significant progress. In 2017, only 34 percent of the respondents said that freedom of speech was most important; in 2021, 61 percent who said so. These are also the two rights that the respondents noted as most often violated in 2021.

Going forward, democratic reformers will need to reckon with these problems to make sure that rights and freedoms are not simply handed down from above again, but upon securing genuine separation of powers, they should actively engage independent media and civil society organizations to educate the public about their rights and serve as watchdogs and exert pressure on authorities to enforce adherence to and protection of these rights.

Since the Russian government launched an unjustified aggressive war in Ukraine, the situation with human rights and basic freedoms in Russia has been deteriorating. According to the Freedom House’s 2023 Freedom in the World report, Russia, which has been rated «not free» since 2004, dropped further in the «global freedom score,“ finding itself alongside countries, like the Republic of Congo and Chad.

Specifically, Freedom House’s analysis shows that in the category of political rights, Russia scored zero points for electoral process (with no fair and free elections and no fair electoral laws) and only a few points for political pluralism (with very limited opportunities to organize political parties or other competitive political groups) and participation (with complete prohibition of political opposition) as well as in the functioning of the government (with no real representation and very little transparency). Indeed, while Russia’s political system envisions a strong presidency, the current president’s powers are de facto largely unlimited: he enjoys «loyalist security forces, a subservient judiciary, a controlled media environment, and a legislature consisting of a ruling party and pliable opposition factions.»

In the category of civil liberties, Russia scored zero points in freedom of expression and belief (with no independent media, no academic freedom, and very narrow opportunities to freely express personal views on political or other sensitive subjects as well as freely practice religious beliefs). There is no freedom of assembly and no freedom for NGOs, especially human rights organizations, to do their work. In terms of the rule of law, there is no protection from the illegitimate use of physical force, and no equal policy application under the law.

The judiciary is deemed almost entirely dependent and there is almost no due process in civil and criminal matters. The score is slightly better in terms of personal autonomy and individual rights, but only if compared to previous categories.

Following the February 2022 invasion in Ukraine, Russia was expelled from the Council of Europe, which allowed Russian authorities to stop pretending that they adhere to European laws, principles, and values. In September 2022, Russia ceased to be a party to the European Convention on Human Rights, Russian petitions to the European Court of Human Rights were suspended, although the Court consequently decided to proceed with reviewing the admitted cases.

A break with the ECtHR was a logical continuation of the Kremlin’s policies in recent years. As part of the 2020 constitutional reform, Russia had already adopted amendments that «decisions of interstate bodies» (e.g. ECtHR) shall not be «subject to enforcement in the Russian Federation» if they run counter to the Constitution.

In April 2022, the United Nations General Assembly’s vote also suspended Russia from the UN Human Rights Council for gross and systematic violations of human rights. Previously, Libya was similarly suspended from UNHRC in 2011 for violent repression of protests by Muammar Gaddafi’s regime. In October 2022, the UNHRC appointed a Special Rapporteur to investigate human rights abuses in Russia — an unprecedented move that for the first time in the Council’s history targets one of the five permanent members of the Security Council.

Several investigations into Russia’s human rights abuses were initiated in 2022 under the Moscow Mechanism (human dimension) of the Organization for Security and Cooperation (OSCE). In September 2022, an in‑depth analysis of Russia’s legislative and administrative practices was delivered based on decisions by the ECtHR, opinions by the Venice Commission, statements by the OSCE’s autonomous institutions, reports, and testimonies by civil society, etc. Regarding the legislative changes in the realms of freedom of association, freedom of expression, and freedom of peaceful assembly, the report concluded that «Russian legislation is obsessed with restricting these rights more and more. […] Russian legislation in this area is clearly incompatible with the rule of law. On the contrary, the multitude of detailed provisions gives the authorities wide discretionary powers and thus provides the basis for arbitrariness.” Another report on human rights violations delivered at the end of December 2022 concluded that «with its internal clampdown on human rights and fundamental freedoms, the Russian Federation has helped prepare the ground for its war of aggression against Ukraine.»

It should be noted that Russia’s war in Ukraine opened an entirely new dimension of human rights abuses, including violations of Russian citizens’ rights during mass conscription, the enlisting of convicts into private military companies, extrajudicial executions, detentions of those who refuse to participate in the war in illegal prisons, as well as violations of the rights of Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilians, including children. Another area concerns human rights, violations of humanitarian law, and war crimes, including willful killings, attacks on civilians, unlawful confinement, torture, rape, and forced transfers and deportations of children committed by Russia in Ukraine.

In the future, the results of the special rapporteurs’ work for the OSCE and the UNHRC could become the basis for reforming Russia into a state that respects the rule of law and where the fundamental human rights and civil liberties are applied indiscriminately.

Since the Russian government launched an unjustified aggressive war in Ukraine, the situation with human rights and basic freedoms in Russia has been deteriorating. According to the Freedom House’s 2023 Freedom in the World report, Russia, which has been rated «not free» since 2004, dropped further in the «global freedom score,“ finding itself alongside countries, like the Republic of Congo and Chad.

Specifically, Freedom House’s analysis shows that in the category of political rights, Russia scored zero points for electoral process (with no fair and free elections and no fair electoral laws) and only a few points for political pluralism (with very limited opportunities to organize political parties or other competitive political groups) and participation (with complete prohibition of political opposition) as well as in the functioning of the government (with no real representation and very little transparency). Indeed, while Russia’s political system envisions a strong presidency, the current president’s powers are de facto largely unlimited: he enjoys «loyalist security forces, a subservient judiciary, a controlled media environment, and a legislature consisting of a ruling party and pliable opposition factions.»

In the category of civil liberties, Russia scored zero points in freedom of expression and belief (with no independent media, no academic freedom, and very narrow opportunities to freely express personal views on political or other sensitive subjects as well as freely practice religious beliefs). There is no freedom of assembly and no freedom for NGOs, especially human rights organizations, to do their work. In terms of the rule of law, there is no protection from the illegitimate use of physical force, and no equal policy application under the law.

The judiciary is deemed almost entirely dependent and there is almost no due process in civil and criminal matters. The score is slightly better in terms of personal autonomy and individual rights, but only if compared to previous categories.

Following the February 2022 invasion in Ukraine, Russia was expelled from the Council of Europe, which allowed Russian authorities to stop pretending that they adhere to European laws, principles, and values. In September 2022, Russia ceased to be a party to the European Convention on Human Rights, Russian petitions to the European Court of Human Rights were suspended, although the Court consequently decided to proceed with reviewing the admitted cases.

A break with the ECtHR was a logical continuation of the Kremlin’s policies in recent years. As part of the 2020 constitutional reform, Russia had already adopted amendments that «decisions of interstate bodies» (e.g. ECtHR) shall not be «subject to enforcement in the Russian Federation» if they run counter to the Constitution.

In April 2022, the United Nations General Assembly’s vote also suspended Russia from the UN Human Rights Council for gross and systematic violations of human rights. Previously, Libya was similarly suspended from UNHRC in 2011 for violent repression of protests by Muammar Gaddafi’s regime. In October 2022, the UNHRC appointed a Special Rapporteur to investigate human rights abuses in Russia — an unprecedented move that for the first time in the Council’s history targets one of the five permanent members of the Security Council.

Several investigations into Russia’s human rights abuses were initiated in 2022 under the Moscow Mechanism (human dimension) of the Organization for Security and Cooperation (OSCE). In September 2022, an in‑depth analysis of Russia’s legislative and administrative practices was delivered based on decisions by the ECtHR, opinions by the Venice Commission, statements by the OSCE’s autonomous institutions, reports, and testimonies by civil society, etc. Regarding the legislative changes in the realms of freedom of association, freedom of expression, and freedom of peaceful assembly, the report concluded that «Russian legislation is obsessed with restricting these rights more and more. […] Russian legislation in this area is clearly incompatible with the rule of law. On the contrary, the multitude of detailed provisions gives the authorities wide discretionary powers and thus provides the basis for arbitrariness.” Another report on human rights violations delivered at the end of December 2022 concluded that «with its internal clampdown on human rights and fundamental freedoms, the Russian Federation has helped prepare the ground for its war of aggression against Ukraine.»

It should be noted that Russia’s war in Ukraine opened an entirely new dimension of human rights abuses, including violations of Russian citizens’ rights during mass conscription, the enlisting of convicts into private military companies, extrajudicial executions, detentions of those who refuse to participate in the war in illegal prisons, as well as violations of the rights of Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilians, including children. Another area concerns human rights, violations of humanitarian law, and war crimes, including willful killings, attacks on civilians, unlawful confinement, torture, rape, and forced transfers and deportations of children committed by Russia in Ukraine.

In the future, the results of the special rapporteurs’ work for the OSCE and the UNHRC could become the basis for reforming Russia into a state that respects the rule of law and where the fundamental human rights and civil liberties are applied indiscriminately.

The human rights situation in Russia had been deteriorating before the full‑fledged war in Ukraine. Freedom House estimates that Russia’s overall score with regards to political rights and civil freedoms has dropped by 11 points over the last decade — from the already low 27 down to 16 out of 100.

In 2012, Russia introduced limits on public assemblies, re‑criminalized libel, expanded the definition of «treason» to criminalize involvement in international human rights advocacy, forced NGOs that receive foreign funding and engage in political activity (vaguely defined) to register as «foreign agents,“ and imposed new restrictions on internet content.

In 2013, Russian parliament adopted new laws restricting LGBTI rights and freedom of expression and infringing on the right to privacy. In 2014, following the Ukraine crisis, annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbass, Russia imposed further harsh restrictions on media and independent groups. Bloggers with more than 3,000 daily visitors were required to register as mass media, custodial terms were introduced for extremist calls on the Internet, including re‑posts on social media, «separatist» calls were criminalized, foreign ownership of Russian media was severely restricted, and Russian Internet users were prohibited from storing personal data on foreign servers.

Year 2015 was marked by the introduction of a new law on «undesirable foreign organizations,” which authorized the extrajudicial banning of foreign or international groups that allegedly undermine Russia’s security, defense, or constitutional order.

A counterterrorism legislative package, known as the «Yarovaya Law» adopted in 2016, required that telecommunications and Internet companies retain copies of all contents of communications for six months, including text messages, voice, data, and images and disclose these data to authorities, on request and without a court order — in violation of privacy and other human rights.

In the runup to the 2018 presidential elections, Russian authorities clamped down on the freedom of assembly: in the first six months of 2017, the number of people that received administrative punishments for supposedly violating the country’s regulations on public gatherings was 2.5 times higher than that of the entire previous year. A leader of political opposition Alexei Navalny, who was killed by Putin regime, and his presidential campaign team were systematically harassed. The law on «undesirable organizations» was more frequently used in 2017, too. The extremist legislation was also more actively used to stifle dissent: the number of people imprisoned for extremist speech almost doubled. The media legislation was amended to allow the government to designate any media organization or information distributor of foreign origin as «foreign media performing the functions of a foreign agent.»

In its 2018 period report on human rights in Russia, the UN Human Rights Council already stated that the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights was not being respected in the country

In 2019, negative trends in Russian only strengthened. The scope of the foreign agent law was expanded, allowing authorities to apply the «foreign agent» status to private persons, including bloggers and independent journalists. First criminal cases were initiated under the law on «undesirable organizations.“ A group of new laws severely restricted freedom of speech, introducing bans on dissemination of «fake news» or expressing «blatant disrespect» for the state (it was later found out that the overwhelming majority of such charges involved alleged insults against Putin). The law on «sovereign Runet» envisaged the creation of a national domain system, providing the government with centralized control of the country’s internet traffic that would enhance its capacity to conduct fine‑grain censorship of internet traffic.

2020 was marked by constitutional reform, with a number of discriminatory principles (e.g. definition of marriage as a union between a man and a woman, mention of «trust in God, transferred by ancestors,” repositioning the Russian language from a national language to «the language of the state‑forming nation, being a part of multi‑national union of equal nations of Russia») finding further legal entrenchment in constitutional amendments. Also, using the COVID‑19 pandemic as a pretext, all mass gatherings were also banned, and police interfered even with single‑person protests, which did not require approval, referring to the social distancing and mandatory mask regime even when protesters wore masks.

It is clear that over the last decade, especially since Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the country has degraded to the level of uncivilized countries in terms of rights and freedoms protection. But the war only accelerated the processes that had already been in place in the country. Major human rights abuses are complemented with adoptions of repressive, restrictive, and discriminatory laws, arbitrary application of law, and deterioration of the quality of justice in general.

The human rights situation in Russia had been deteriorating before the full‑fledged war in Ukraine. Freedom House estimates that Russia’s overall score with regards to political rights and civil freedoms has dropped by 11 points over the last decade — from the already low 27 down to 16 out of 100.

In 2012, Russia introduced limits on public assemblies, re‑criminalized libel, expanded the definition of «treason» to criminalize involvement in international human rights advocacy, forced NGOs that receive foreign funding and engage in political activity (vaguely defined) to register as «foreign agents,“ and imposed new restrictions on internet content.

In 2013, Russian parliament adopted new laws restricting LGBTI rights and freedom of expression and infringing on the right to privacy. In 2014, following the Ukraine crisis, annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbass, Russia imposed further harsh restrictions on media and independent groups. Bloggers with more than 3,000 daily visitors were required to register as mass media, custodial terms were introduced for extremist calls on the Internet, including re‑posts on social media, «separatist» calls were criminalized, foreign ownership of Russian media was severely restricted, and Russian Internet users were prohibited from storing personal data on foreign servers.

Year 2015 was marked by the introduction of a new law on «undesirable foreign organizations,” which authorized the extrajudicial banning of foreign or international groups that allegedly undermine Russia’s security, defense, or constitutional order.

A counterterrorism legislative package, known as the «Yarovaya Law» adopted in 2016, required that telecommunications and Internet companies retain copies of all contents of communications for six months, including text messages, voice, data, and images and disclose these data to authorities, on request and without a court order — in violation of privacy and other human rights.

In the runup to the 2018 presidential elections, Russian authorities clamped down on the freedom of assembly: in the first six months of 2017, the number of people that received administrative punishments for supposedly violating the country’s regulations on public gatherings was 2.5 times higher than that of the entire previous year. A leader of political opposition Alexei Navalny, who was killed by Putin regime, and his presidential campaign team were systematically harassed. The law on «undesirable organizations» was more frequently used in 2017, too. The extremist legislation was also more actively used to stifle dissent: the number of people imprisoned for extremist speech almost doubled. The media legislation was amended to allow the government to designate any media organization or information distributor of foreign origin as «foreign media performing the functions of a foreign agent.»

In its 2018 period report on human rights in Russia, the UN Human Rights Council already stated that the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights was not being respected in the country

In 2019, negative trends in Russian only strengthened. The scope of the foreign agent law was expanded, allowing authorities to apply the «foreign agent» status to private persons, including bloggers and independent journalists. First criminal cases were initiated under the law on «undesirable organizations.“ A group of new laws severely restricted freedom of speech, introducing bans on dissemination of «fake news» or expressing «blatant disrespect» for the state (it was later found out that the overwhelming majority of such charges involved alleged insults against Putin). The law on «sovereign Runet» envisaged the creation of a national domain system, providing the government with centralized control of the country’s internet traffic that would enhance its capacity to conduct fine‑grain censorship of internet traffic.

2020 was marked by constitutional reform, with a number of discriminatory principles (e.g. definition of marriage as a union between a man and a woman, mention of «trust in God, transferred by ancestors,” repositioning the Russian language from a national language to «the language of the state‑forming nation, being a part of multi‑national union of equal nations of Russia») finding further legal entrenchment in constitutional amendments. Also, using the COVID‑19 pandemic as a pretext, all mass gatherings were also banned, and police interfered even with single‑person protests, which did not require approval, referring to the social distancing and mandatory mask regime even when protesters wore masks.

It is clear that over the last decade, especially since Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the country has degraded to the level of uncivilized countries in terms of rights and freedoms protection. But the war only accelerated the processes that had already been in place in the country. Major human rights abuses are complemented with adoptions of repressive, restrictive, and discriminatory laws, arbitrary application of law, and deterioration of the quality of justice in general.

Media reform should be one of the central pieces of the task on restoration of basic rights in Russia. A powerful propaganda machine is one of the pillars of the current regime. Dismantling this machine and democratizing the media space should be a priority for democratic reformers. This task, however, is impossible without a comprehensive reform of the political system and judiciary.

Media reform should be one of the central pieces of the task on restoration of basic rights in Russia. A powerful propaganda machine is one of the pillars of the current regime. Dismantling this machine and democratizing the media space should be a priority for democratic reformers. This task, however, is impossible without a comprehensive reform of the political system and judiciary.

Media reform is inherently linked to restoration of freedom of speech — a basic right whose importance has significantly grown in Russian in recent years. Despite the fact that freedom of speech is formally guaranteed by the Constitution, protection of this right is not a subject of wide public discussion: the state has secured the right to define it for itself. Reformers should start with getting this right back and engage in discussions about the essence and meaning of free speech in Russia.

Freedom of speech cannot be absolute — it is limited by the modern person’s existence in the bounds of civilized society, whose members have rights and freedoms as well as responsibilities. There are limitations when it comes to issues such as right to privacy, libel, obscene behavior, pornography, incitement of hatred, violence and overthrowing of the government, commercial information, and state secrets, national security, etc.

A classic criterion that defines the relationship between freedom and its limitations in democratic societies is the so‑called «principle of harm» put forward by John Stuart Mill in his essay «On Liberty» (1859):

Media reform is inherently linked to restoration of freedom of speech — a basic right whose importance has significantly grown in Russian in recent years. Despite the fact that freedom of speech is formally guaranteed by the Constitution, protection of this right is not a subject of wide public discussion: the state has secured the right to define it for itself. Reformers should start with getting this right back and engage in discussions about the essence and meaning of free speech in Russia.

Freedom of speech cannot be absolute — it is limited by the modern person’s existence in the bounds of civilized society, whose members have rights and freedoms as well as responsibilities. There are limitations when it comes to issues such as right to privacy, libel, obscene behavior, pornography, incitement of hatred, violence and overthrowing of the government, commercial information, and state secrets, national security, etc.

A classic criterion that defines the relationship between freedom and its limitations in democratic societies is the so‑called «principle of harm» put forward by John Stuart Mill in his essay «On Liberty» (1859):

«That principle is, that the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self‑protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. In the part which merely concerns himself, his independence is, of right, absolute. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign.«

«That principle is, that the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self‑protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. In the part which merely concerns himself, his independence is, of right, absolute. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign.«

Freedom of speech exists within a country’s legal system. Thus, the expansive interpretation of freedom of speech in the United States is provided for by the country’s history and the specifics of the American political and legal systems and is therefore different from the more conservative approach practiced in European countries, not to mention developing countries and authoritarian regimes. Developing the Russian definition of freedom of speech, reformers should thus account for legal, political, and social factors that influence the way freedom of speech is perceived by the Russian public.

Freedom of speech exists within a country’s legal system. Thus, the expansive interpretation of freedom of speech in the United States is provided for by the country’s history and the specifics of the American political and legal systems and is therefore different from the more conservative approach practiced in European countries, not to mention developing countries and authoritarian regimes. Developing the Russian definition of freedom of speech, reformers should thus account for legal, political, and social factors that influence the way freedom of speech is perceived by the Russian public.

Effective media reform needs thorough preparation, which includes analyzing the mistakes of previous Russian transitions and experiences in other post‑Soviet and authoritarian regimes, as well as reflecting on the existing structural problems in the Russian media system. Ideally, these processes should take place in an open discussion with the participation of independent experts and members of the media and civil society.

During the democratic transition of the 1990s, media reforms in the post‑Soviet space typically followed two stages: first, censorship was formally abolished, and freedom of speech was pronounced, and second, the public space was opened up for members of society. The adoption of democratic legislation and regulation of the media sphere was the fulcrum of these media reforms. It was assumed that market mechanisms and «correct» laws would bring the media up to democratic standards.

However, it soon became clear that in most post‑Soviet countries, including Russia, media laws were «imitational»: legislation was often directly borrowed (sometimes simply by translation) from developed democracies, where it corresponded to national media systems. Such borrowing did not account for the specifics of post‑Soviet political culture, the existing power structures and their relations with the media, a weak and passive civil society, or the historical context of each country. As analyses of these media reforms’ results show, they were most successful when the reform’s agenda and plan were developed with the participation of civil society members, journalists, and researchers (e.g., Croatia in the late 1990s). When media reform was handed down «from above,“ its results were always worse. Reformers should keep these mistakes in mind.

Reformers might be interested in Poland’s experience, where, similarly to Russia, a dual (state corporatist) media model has been identified by media scholars. They can also consider best practices of media policy implementation in Estonia, which holds the 15th place in the 2020 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders. This is higher than all other post‑Soviet countries and some developed democracies, such as the U.S. and the U. K. Important lessons can be learned from the history of German media regulation after 1945, as well as following the reunification of the Federal German Republic and the German Democratic Republic.

Effective media reform needs thorough preparation, which includes analyzing the mistakes of previous Russian transitions and experiences in other post‑Soviet and authoritarian regimes, as well as reflecting on the existing structural problems in the Russian media system. Ideally, these processes should take place in an open discussion with the participation of independent experts and members of the media and civil society.

During the democratic transition of the 1990s, media reforms in the post‑Soviet space typically followed two stages: first, censorship was formally abolished, and freedom of speech was pronounced, and second, the public space was opened up for members of society. The adoption of democratic legislation and regulation of the media sphere was the fulcrum of these media reforms. It was assumed that market mechanisms and «correct» laws would bring the media up to democratic standards.

However, it soon became clear that in most post‑Soviet countries, including Russia, media laws were «imitational»: legislation was often directly borrowed (sometimes simply by translation) from developed democracies, where it corresponded to national media systems. Such borrowing did not account for the specifics of post‑Soviet political culture, the existing power structures and their relations with the media, a weak and passive civil society, or the historical context of each country. As analyses of these media reforms’ results show, they were most successful when the reform’s agenda and plan were developed with the participation of civil society members, journalists, and researchers (e.g., Croatia in the late 1990s). When media reform was handed down «from above,” its results were always worse. Reformers should keep these mistakes in mind.

Reformers might be interested in Poland’s experience, where, similarly to Russia, a dual (state corporatist) media model has been identified by media scholars. They can also consider best practices of media policy implementation in Estonia, which holds the 15th place in the 2020 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders. This is higher than all other post‑Soviet countries and some developed democracies, such as the U.S. and the U. K. Important lessons can be learned from the history of German media regulation after 1945, as well as following the reunification of the Federal German Republic and the German Democratic Republic.

Numerous analyses of the Russian media system identify the following problems:

Numerous analyses of the Russian media system identify the following problems:

A media reform plan that provides solutions for all of these problems can be used as a blueprint. In each case, the following objectives should be seen as priorities: liberalization of repressive legislation and regulation of the media; dismantlement of the propaganda apparatus created to promote the current regime’s interests; and liberalization of the monocentric mass media model (e.g., through the privatization of the state’s major media assets). Other problems of the Russian media system can be addressed in the long‑term if the initial democratization stages are successfully implemented.

To start off, reformers must create a task force, which should include media scholars, independent journalists, members of civil society and groups that protect journalists’ rights, media reform experts, as well as media owners. Ideally, the reform should be based on a wide approach that aims to transform the entire media system and not just the pertinent media law, but, more realistically, reformers could use a modular approach, one based on the most optimal components of the reform that can be implemented in the present moment.

Some of the suggested first steps for the task force include:

A media reform plan that provides solutions for all of these problems can be used as a blueprint. In each case, the following objectives should be seen as priorities: liberalization of repressive legislation and regulation of the media; dismantlement of the propaganda apparatus created to promote the current regime’s interests; and liberalization of the monocentric mass media model (e.g., through the privatization of the state’s major media assets). Other problems of the Russian media system can be addressed in the long‑term if the initial democratization stages are successfully implemented.

To start off, reformers must create a task force, which should include media scholars, independent journalists, members of civil society and groups that protect journalists’ rights, media reform experts, as well as media owners. Ideally, the reform should be based on a wide approach that aims to transform the entire media system and not just the pertinent media law, but, more realistically, reformers could use a modular approach, one based on the most optimal components of the reform that can be implemented in the present moment.

Some of the suggested first steps for the task force include:

When choosing the new media model, reformers should also review the mistakes made during earlier attempts at transition — attempts to borrow or imitate Western models or to impose media reform on the public «from above.“ The optimal solution would be reaching a consensus decision on the desired media model over the course of open discussions involving all the members of the task force. Special attention should be paid to such factors as the government’s influence on media development (e.g., through subsidies), media policy, laws and regulations (in particular, to prevent concentration of media assets), as well as the media’s dual role as a democratic institution and as a business. Discussion of the future media model must be directly linked to the development of political reform, including choosing the best‑fitting political model for Russia.

Research on media reform in other countries shows that media activists campaigning for the protection of freedom of speech play an important part in its successful implementation. Educating and informing the public about its rights, these activists bring more people into the discussion, facilitating the development of civic consciousness and laying the groundwork for future public support of the reform.

To implement the first steps of transition, reformers need to create a public commission on media reform (potentially modeled after the task force), which will face a number of crucial questions concerning the scale and radicality of the reform at this stage and will need to develop clear legal and economic mechanisms for the demonopolization and deconcentration of the media system, closure or suspension of propaganda outlets, firing of odious media figures, etc. The transparency and universality of these mechanisms will facilitate public acceptance of the reform.

Here the reformers can learn from the experience of the United States, where the public Commission on Freedom of the Press (also known as the Hutchins Commission) was created in 1947 to review the state of U.S. media. In its final report, titled «A Free and Responsible Press,” the commission offered the following duties the media must perform in order to be considered free and responsible:

When choosing the new media model, reformers should also review the mistakes made during earlier attempts at transition — attempts to borrow or imitate Western models or to impose media reform on the public «from above.“ The optimal solution would be reaching a consensus decision on the desired media model over the course of open discussions involving all the members of the task force. Special attention should be paid to such factors as the government’s influence on media development (e.g., through subsidies), media policy, laws and regulations (in particular, to prevent concentration of media assets), as well as the media’s dual role as a democratic institution and as a business. Discussion of the future media model must be directly linked to the development of political reform, including choosing the best‑fitting political model for Russia.

Research on media reform in other countries shows that media activists campaigning for the protection of freedom of speech play an important part in its successful implementation. Educating and informing the public about its rights, these activists bring more people into the discussion, facilitating the development of civic consciousness and laying the groundwork for future public support of the reform.

To implement the first steps of transition, reformers need to create a public commission on media reform (potentially modeled after the task force), which will face a number of crucial questions concerning the scale and radicality of the reform at this stage and will need to develop clear legal and economic mechanisms for the demonopolization and deconcentration of the media system, closure or suspension of propaganda outlets, firing of odious media figures, etc. The transparency and universality of these mechanisms will facilitate public acceptance of the reform.

Here the reformers can learn from the experience of the United States, where the public Commission on Freedom of the Press (also known as the Hutchins Commission) was created in 1947 to review the state of U.S. media. In its final report, titled «A Free and Responsible Press,” the commission offered the following duties the media must perform in order to be considered free and responsible:

The commission also emphasized the media’s role as a political institution — to serve as a «watchdog» over the state, and to inform and educate citizens in a way that makes them capable of self‑governance. Today, one may add to the list the media’s responsibilities to guarantee political pluralism and the inclusivity of public discourse.

The commission also emphasized the media’s role as a political institution — to serve as a «watchdog» over the state, and to inform and educate citizens in a way that makes them capable of self‑governance. Today, one may add to the list the media’s responsibilities to guarantee political pluralism and the inclusivity of public discourse.

1. End the persecution of journalists based on their professional activity

Reformers must end the illegal prosecution of journalists, review and close criminal and administrative cases initiated against them, release those arrested or serving prison terms, and offer due compensation to the victims of repressive law enforcement.

2. Repeal repressive media laws and regulations

Over the past two decades, over 20 federal repressive laws have been introduced to Russian media legislation, which have had a detrimental effect on the work of the media overall, but especially on independent journalists. These laws should be repealed.

3. Dismantle the propaganda apparatus

The dismantling of the existing propaganda apparatus and disinformation system built by the current regime is a mandatory step of media reform; television networks and publishers that were instrumental in furthering the regime’s interests and manipulating public opinion must be suspended or shut down.

Below is a preliminary list of state agencies whose powers should be amended with regards to restoration of the freedom of information.

Government Agencies

Here, reformers should aim to decrease the state’s involvement in the regulation of media work and the media market at large, as well as curtail the control and oversight functions of various agencies. Below are the main government bodies that currently formulate and regulate Russian information policy, whose work should be substantially revised (e.g., administration change, closure, profound reform).

Presidential administration is responsible for the state information policy. It is also shared by the Presidential Domestic Policy Directorate; the Presidential Directorate for Public Relations and Communications; the Presidential Directorate for Social Projects; and the Presidential Directorate for the Development of Information and Communication Technology and Communication Infrastructure.

Mintsifra (the Ministry of Digital Development, Communications, and Mass Communications) is responsible for the state policy on and normative and legal regulation of information technologies, electronic and mail communications, mass communications and media, including electronic media (internet, TV, and radio communications, new technologies), press, publishing, and printing activity, as well as personal data processing.

Roskomnadzor (Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology, and Mass Media) is responsible for control and oversight of state policy implementation in the aforementioned areas. In particular, it is responsible for licensing mass media, radio frequencies (along with the Defense Ministry and the Federal Protective Service), regulating the internet, etc.

State Duma contributes to regulation through its Committee on Information Policy, Information Technology and Communications and Commission on the Investigation of Foreign Interference in Russia’s Internal Affairs.

Federation Council contributes to regulation through its Interim Commission on Information Policy and Cooperation with the Media, Interim Commission for Legislative Regulation of Cybersecurity and Digital Technologies, and Interim Commission for the Protection of State Sovereignty and Prevention of Interference in Russia’s Internal Affairs.

Media Assets

Considering the long traditions of the Russian government’s strong control over the media system, growing media etatization (state interference), and the ruling regime’s efforts in building a powerful propaganda machine, this part of the reform is fraught with many challenges and requires a complex approach. Reformers should pay special attention to the inventory of Russian media assets at the preliminary stage and identify those that should or should not be reformed.

1. End the persecution of journalists based on their professional activity

Reformers must end the illegal prosecution of journalists, review and close criminal and administrative cases initiated against them, release those arrested or serving prison terms, and offer due compensation to the victims of repressive law enforcement.

2. Repeal repressive media laws and regulations

Over the past two decades, over 20 federal repressive laws have been introduced to Russian media legislation, which have had a detrimental effect on the work of the media overall, but especially on independent journalists. These laws should be repealed.

3. Dismantle the propaganda apparatus

The dismantling of the existing propaganda apparatus and disinformation system built by the current regime is a mandatory step of media reform; television networks and publishers that were instrumental in furthering the regime’s interests and manipulating public opinion must be suspended or shut down.

Below is a preliminary list of state agencies whose powers should be amended with regards to restoration of the freedom of information.

Government Agencies

Here, reformers should aim to decrease the state’s involvement in the regulation of media work and the media market at large, as well as curtail the control and oversight functions of various agencies. Below are the main government bodies that currently formulate and regulate Russian information policy, whose work should be substantially revised (e.g., administration change, closure, profound reform).

Presidential administration is responsible for the state information policy. It is also shared by the Presidential Domestic Policy Directorate; the Presidential Directorate for Public Relations and Communications; the Presidential Directorate for Social Projects; and the Presidential Directorate for the Development of Information and Communication Technology and Communication Infrastructure.

Mintsifra (the Ministry of Digital Development, Communications, and Mass Communications) is responsible for the state policy on and normative and legal regulation of information technologies, electronic and mail communications, mass communications and media, including electronic media (internet, TV, and radio communications, new technologies), press, publishing, and printing activity, as well as personal data processing.

Roskomnadzor (Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology, and Mass Media) is responsible for control and oversight of state policy implementation in the aforementioned areas. In particular, it is responsible for licensing mass media, radio frequencies (along with the Defense Ministry and the Federal Protective Service), regulating the internet, etc.

State Duma contributes to regulation through its Committee on Information Policy, Information Technology and Communications and Commission on the Investigation of Foreign Interference in Russia’s Internal Affairs.

Federation Council contributes to regulation through its Interim Commission on Information Policy and Cooperation with the Media, Interim Commission for Legislative Regulation of Cybersecurity and Digital Technologies, and Interim Commission for the Protection of State Sovereignty and Prevention of Interference in Russia’s Internal Affairs.

Media Assets

Considering the long traditions of the Russian government’s strong control over the media system, growing media etatization (state interference), and the ruling regime’s efforts in building a powerful propaganda machine, this part of the reform is fraught with many challenges and requires a complex approach. Reformers should pay special attention to the inventory of Russian media assets at the preliminary stage and identify those that should or should not be reformed.

4. Engage the surviving independent media

Over the course of the reform, a number of prominent Russian media outlets might be closed, suspended, or subjected to significant reformatting. The gaps, especially in television broadcasting, can be bridged by engaging the resources of independent media projects (journalists, editors, producers, media managers). Delivering objective information to the public about the implementation of media reform (and what is to come) will be key to its success. Therefore, as noted earlier, at the preliminary stage reformers should think this process through and develop mechanisms for tentative or long‑term recruitment of independent professionals without compromising their status.

At this stage, reformers can also support independent outlets (through subsidies or tax benefits) that have proved their competence, professionalism, and commitment to the ethical standards of journalism under the conditions of Russian authoritarianism. Here reformers might tap the experiences of Scandinavian countries (Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Iceland), which traditionally rank high in press freedom indices. They have developed state mechanisms to support the media and secure its status as the «fourth estate.“ For example, Sweden has had a system of media subsidies since the 1960s, allowing for lower entry barriers to circulation and distribution systems, implementing regular technological updates, developing regional journalism, and promoting diversity and pluralism within the media.

4. Engage the surviving independent media

Over the course of the reform, a number of prominent Russian media outlets might be closed, suspended, or subjected to significant reformatting. The gaps, especially in television broadcasting, can be bridged by engaging the resources of independent media projects (journalists, editors, producers, media managers). Delivering objective information to the public about the implementation of media reform (and what is to come) will be key to its success. Therefore, as noted earlier, at the preliminary stage reformers should think this process through and develop mechanisms for tentative or long‑term recruitment of independent professionals without compromising their status.

At this stage, reformers can also support independent outlets (through subsidies or tax benefits) that have proved their competence, professionalism, and commitment to the ethical standards of journalism under the conditions of Russian authoritarianism. Here reformers might tap the experiences of Scandinavian countries (Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Iceland), which traditionally rank high in press freedom indices. They have developed state mechanisms to support the media and secure its status as the «fourth estate.” For example, Sweden has had a system of media subsidies since the 1960s, allowing for lower entry barriers to circulation and distribution systems, implementing regular technological updates, developing regional journalism, and promoting diversity and pluralism within the media.

A return to basic freedoms is impossible without engaging Russian civil society into the transition process. A «strong civil society» is the sphere of uncoerced human association between the individual and the state and is one of the cornerstones of democracy, «good governance,“ pluralism, and the achievement of important social and economic goals. Civil society is needed to facilitate social cohesion and develop common values. Modern states are too complex to be based upon the state and the market only. Civil society offers a form of citizens’ participation in governing or representing their interests outside political structures. The values of human dignity and equality that undergird fundamental human rights and freedoms can also be facilitated by civil society, which often encourages innovation and transformation.

It is often argued that civil society can only exist in the liberal Western environment: a chess club in Russia, while being a human association, would not constitute a civil society organization. Yet, Russian civil society, despite being described as weak and passive, has a powerful potential for engagement, especially on social issues.

One of the mistakes of the 1990s reforms in post‑Communist countries was direct exporting of the civil society practices outside the Western political and economic settings, which had often resulted in mimicry and ineffectiveness. Another explanation and that those civil societies were oppositional in nature: following the initial revolutionary spark, activists left the streets and their civic organizations, while societies remained largely passive and depoliticized.

However, over the last 20 years, Russian civil society has made significant progress. Formally, there are over 200,000 registered civil society organizations in Russia today, although exact statistics are unknown, since this number includes state corporations that have nonprofit status in Russia, thus distorting data. Still, this is a significant number that should not be ignored.

A return to basic freedoms is impossible without engaging Russian civil society into the transition process. A «strong civil society» is the sphere of uncoerced human association between the individual and the state and is one of the cornerstones of democracy, «good governance,” pluralism, and the achievement of important social and economic goals. Civil society is needed to facilitate social cohesion and develop common values. Modern states are too complex to be based upon the state and the market only. Civil society offers a form of citizens’ participation in governing or representing their interests outside political structures. The values of human dignity and equality that undergird fundamental human rights and freedoms can also be facilitated by civil society, which often encourages innovation and transformation.

It is often argued that civil society can only exist in the liberal Western environment: a chess club in Russia, while being a human association, would not constitute a civil society organization. Yet, Russian civil society, despite being described as weak and passive, has a powerful potential for engagement, especially on social issues.

One of the mistakes of the 1990s reforms in post‑Communist countries was direct exporting of the civil society practices outside the Western political and economic settings, which had often resulted in mimicry and ineffectiveness. Another explanation and that those civil societies were oppositional in nature: following the initial revolutionary spark, activists left the streets and their civic organizations, while societies remained largely passive and depoliticized.

However, over the last 20 years, Russian civil society has made significant progress. Formally, there are over 200,000 registered civil society organizations in Russia today, although exact statistics are unknown, since this number includes state corporations that have nonprofit status in Russia, thus distorting data. Still, this is a significant number that should not be ignored.

The civil society developed both regardless of the state but also with its help. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the state paid little attention to the nonprofit sector: civil society organizations (CSOs) developed randomly and were mainly supported by foreign funds. Most of the work was done through their enthusiasm and volunteer work.

But with the advent of the so‑called «color revolutions» in various countries, CSOs suddenly found themselves under close surveillance by the state, since many of them participated in the revolutionary events. In Russia, authorities decided to take the nonprofit sector under control and tightened regulation. They started to create and champion loyal nonprofits, e.g. so‑called GONGOs (government‑organized NGOs) to work closely with the state and take up some of its social functions. As a result, many CSOs became largely dependent on the state. Whereas there used to be numerous domestic foundations that distributed budgetary funds for nonprofits, since 2017, all of them were merged into a single Presidential Grants Foundation, which has emerged as the main source of funding for the nonprofits’ social projects.

The authorities also purposefully divided CSOs into either «bad» (opposing the state) or «good» (loyal to the state) category. The latter are the CSOs that provide social services useful to the state, working in the politically benign areas, such as sports, education, and culture. The former are usually engaged in advocacy, such as human rights or pro‑democracy organizations, and are often seen as acting under foreign influence. This division is further spurred by the propaganda media and the introduction of marginalizing and stigmatizing laws, e.g. on «undesirable» organizations or on «foreign agents.“

Still, despite significant pressures from the state, Russian civil society also saw a number of positive trends. Over the last 20 years, philanthropy and charities have flourished in Russia, private donations have skyrocketed, and fundraising has become ubiquitous. Popularity of volunteering is another significant development, which was originally encouraged by the state which saw both volunteers and charities as additional resources for social projects that could be implemented without zero cost for the state budget. The nonprofit sector has also grown more professionally, boosted using new information technologies, which allowed for creation of various network communities and structures, joint activities, and collaborations, including international experience. Self‑organization within the nonprofit sector has also increased, and there is a growing interest in social entrepreneurship and social investment. Expansion of informal civic activities often involving young people is yet another prominent trait of Russian civil society. These activities include not only protests, but also proactive self‑organization to solve common problems.

In other words, reformers should not discount Russian civil society as weak and passive but rather tap its potential and let it develop with full force. Associations, non‑government organizations, charities, and other civic initiative groups play an important role in exerting pressure on state power, serving as safeguards of basic freedom and democratic processes. They also provide opportunities and means for ordinary people to become involved in the protection of human rights, advocacy, and eventually political participation.

The civil society developed both regardless of the state but also with its help. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the state paid little attention to the nonprofit sector: civil society organizations (CSOs) developed randomly and were mainly supported by foreign funds. Most of the work was done through their enthusiasm and volunteer work.

But with the advent of the so‑called «color revolutions» in various countries, CSOs suddenly found themselves under close surveillance by the state, since many of them participated in the revolutionary events. In Russia, authorities decided to take the nonprofit sector under control and tightened regulation. They started to create and champion loyal nonprofits, e.g. so‑called GONGOs (government‑organized NGOs) to work closely with the state and take up some of its social functions. As a result, many CSOs became largely dependent on the state. Whereas there used to be numerous domestic foundations that distributed budgetary funds for nonprofits, since 2017, all of them were merged into a single Presidential Grants Foundation, which has emerged as the main source of funding for the nonprofits’ social projects.

The authorities also purposefully divided CSOs into either «bad» (opposing the state) or «good» (loyal to the state) category. The latter are the CSOs that provide social services useful to the state, working in the politically benign areas, such as sports, education, and culture. The former are usually engaged in advocacy, such as human rights or pro‑democracy organizations, and are often seen as acting under foreign influence. This division is further spurred by the propaganda media and the introduction of marginalizing and stigmatizing laws, e.g. on «undesirable» organizations or on «foreign agents.”

Still, despite significant pressures from the state, Russian civil society also saw a number of positive trends. Over the last 20 years, philanthropy and charities have flourished in Russia, private donations have skyrocketed, and fundraising has become ubiquitous. Popularity of volunteering is another significant development, which was originally encouraged by the state which saw both volunteers and charities as additional resources for social projects that could be implemented without zero cost for the state budget. The nonprofit sector has also grown more professionally, boosted using new information technologies, which allowed for creation of various network communities and structures, joint activities, and collaborations, including international experience. Self‑organization within the nonprofit sector has also increased, and there is a growing interest in social entrepreneurship and social investment. Expansion of informal civic activities often involving young people is yet another prominent trait of Russian civil society. These activities include not only protests, but also proactive self‑organization to solve common problems.

In other words, reformers should not discount Russian civil society as weak and passive but rather tap its potential and let it develop with full force. Associations, non‑government organizations, charities, and other civic initiative groups play an important role in exerting pressure on state power, serving as safeguards of basic freedom and democratic processes. They also provide opportunities and means for ordinary people to become involved in the protection of human rights, advocacy, and eventually political participation.

At the early stages of transition, reformers can follow a blueprint of restoration of basic freedom similar to the one outlined above with regards to media reform.

1. End the persecution of civil society activists and organizations

This includes ending their illegal prosecution, reviewing and closing criminal and administrative cases against them, releasing those arrested or serving prison terms, and duly compensating the victims of repressive law enforcement.

2. Repeal repressive laws and regulations that regulate the nonprofit sector

First and foremost, reformers should repeal the laws on «foreign agents» and «undesirable» organizations. As of the end of March 2023, there were 565 «foreign agents» of various types and 77 «undesirable» organizations in Russia’s Ministry of Justice’s respective blacklists. These lists should be eliminated, and reputations of the blacklisted individuals and organizations officially restored.

3. Bring back exiles and re‑engage with international civil society groups

Reformers’ work on restoring basic freedoms will benefit from the experience of the human rights and civil society organizations that were forced into exile to be able to continue their operations. Restoration of the prominent human rights organizations that were forcefully and illegally shut down (e.g. Memorial, Moscow Helsinki Group) is another crucial task. Re‑engaging with international and foreign civil society groups will also be beneficial.

As a guiding principle, reformers should remember that civil society is a sphere that exists apart from the state. It is an area of human life where people come together and form groups, pursue common interests, communicate about important issues, and take action to achieve their goals and solve common problems. If these associations are controlled or simply tolerated by the state by default and not by design, there is no guarantee that the state would not interfere. Therefore, the state needs to be bound by rule of law to not interfere with the civil society. And creating legal and practical mechanisms for defining and safeguarding these boundaries is a task for further stages of the transition reforms.

At the early stages of transition, reformers can follow a blueprint of restoration of basic freedom similar to the one outlined above with regards to media reform.

1. End the persecution of civil society activists and organizations

This includes ending their illegal prosecution, reviewing and closing criminal and administrative cases against them, releasing those arrested or serving prison terms, and duly compensating the victims of repressive law enforcement.

2. Repeal repressive laws and regulations that regulate the nonprofit sector

First and foremost, reformers should repeal the laws on «foreign agents» and «undesirable» organizations. As of the end of March 2023, there were 565 «foreign agents» of various types and 77 «undesirable» organizations in Russia’s Ministry of Justice’s respective blacklists. These lists should be eliminated, and reputations of the blacklisted individuals and organizations officially restored.

3. Bring back exiles and re‑engage with international civil society groups

Reformers’ work on restoring basic freedoms will benefit from the experience of the human rights and civil society organizations that were forced into exile to be able to continue their operations. Restoration of the prominent human rights organizations that were forcefully and illegally shut down (e.g. Memorial, Moscow Helsinki Group) is another crucial task. Re‑engaging with international and foreign civil society groups will also be beneficial.

As a guiding principle, reformers should remember that civil society is a sphere that exists apart from the state. It is an area of human life where people come together and form groups, pursue common interests, communicate about important issues, and take action to achieve their goals and solve common problems. If these associations are controlled or simply tolerated by the state by default and not by design, there is no guarantee that the state would not interfere. Therefore, the state needs to be bound by rule of law to not interfere with the civil society. And creating legal and practical mechanisms for defining and safeguarding these boundaries is a task for further stages of the transition reforms.

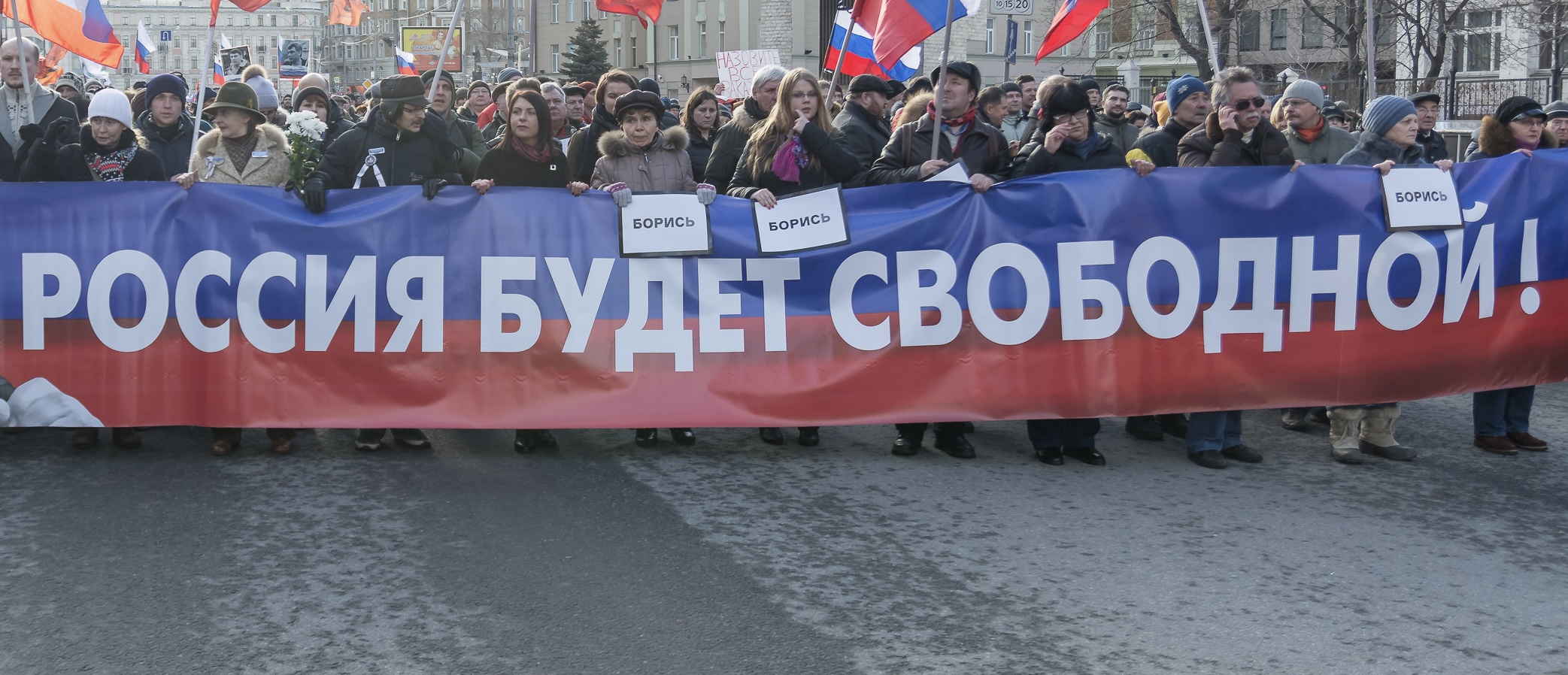

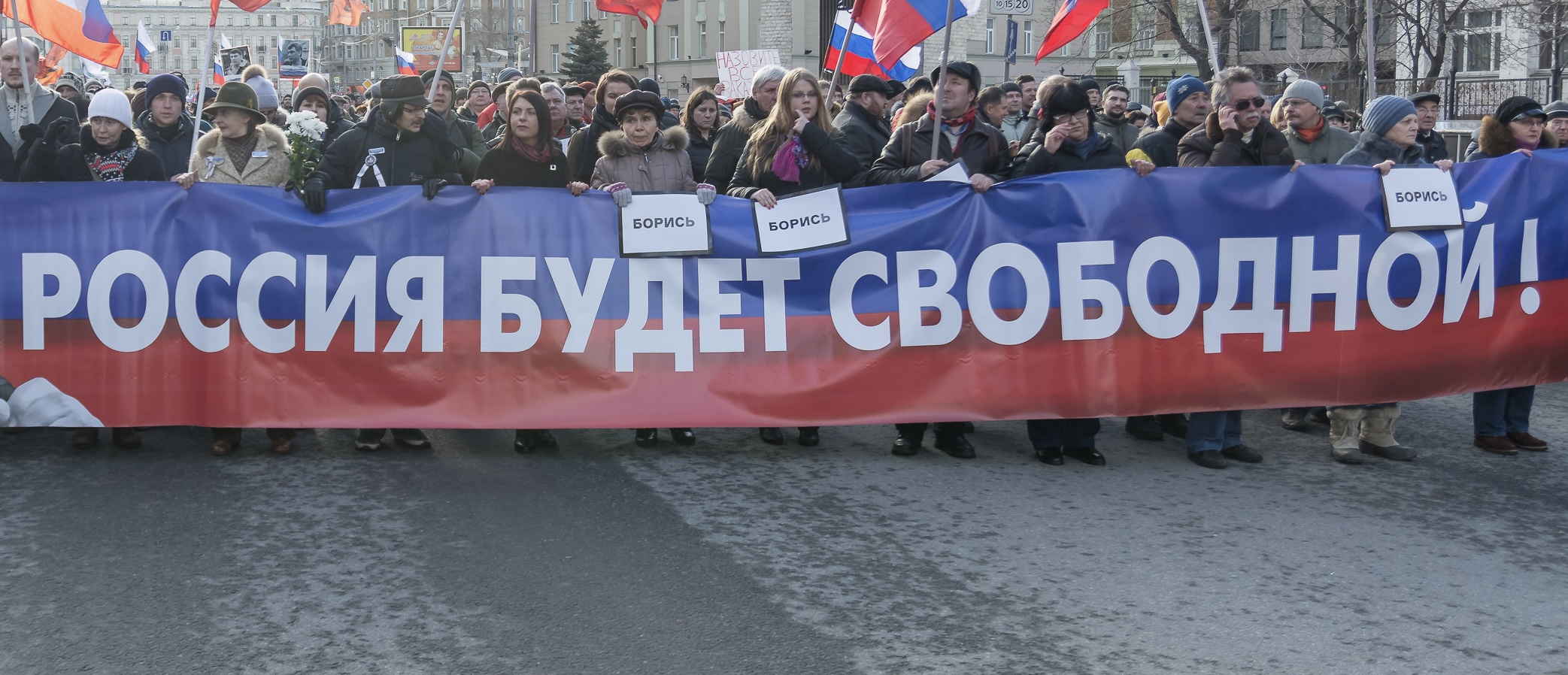

The war in Ukraine has had a negative impact on freedom of assembly in Russia. Mass protests against the invasion lack coordination, and people who go out with solitary anti‑war pickets are regularly detained. Detentions and administrative persecution of participants of peaceful protest actions in Russia number in the thousands: since the beginning of the full‑scale invasion of Ukraine, the security forces have made more than 19,000 arrests for their anti‑war position. Courts impose fines totaling tens of millions of rubles annually, government agencies dismiss employees who protest, and universities warn students against participating in uncoordinated actions and threaten expulsions. In 2023, at least 74 people criminal cases were initiated against Russians detained at anti‑war rallies and protests against mobilization.

Having worked with the issue of restriction of freedom of assembly in Russia for many years, we are convinced that improvements are impossible without corresponding changes in many other areas, such as improving the overall quality of regulatory regulation, guarantees of independent and fair trial, accountability and transparency of government actions, and the responsibility of officials for decisions taken. But no less important is the task of articulating specific solutions. For example, the practice of arbitrarily outlawing public events or an imbalance of responsibility that leads to the suppression of people’s desire to exercise the right to freedom of assembly is a composit of many phenomena.

In the process of reforming the situation with freedom of assembly, the following five key issues will need to be resolved:

1. The ban on spontaneous gatherings and the problem of coordination

Russian legislation does not provide for the legal possibility of holding a spontaneous gathering. Any public event must be coordinated with the authorities in advance. The deadlines for submitting a notification are strictly regulated by law, and the broad powers of the authorities to control the location and timing of actions in practice lead to their ability to prevent any undesirable events from taking place. The «uncoordinated» status of the meeting leads to a number of negative consequences — from the forceful dispersion of the event and the persecution of its participants and alleged organizers, to a ban on the dissemination of information about such actions. The steps necessary to reform the coordination system are discussed in detail in the report of the Memorial Human Rights Center and OVD‑Info in the context of the execution of the ECHR ruling in the case «Lashmankin and Others v. Russia». The main points are:

The war in Ukraine has had a negative impact on freedom of assembly in Russia. Mass protests against the invasion lack coordination, and people who go out with solitary anti‑war pickets are regularly detained. Detentions and administrative persecution of participants of peaceful protest actions in Russia number in the thousands: since the beginning of the full‑scale invasion of Ukraine, the security forces have made more than 19,000 arrests for their anti‑war position. Courts impose fines totaling tens of millions of rubles annually, government agencies dismiss employees who protest, and universities warn students against participating in uncoordinated actions and threaten expulsions. In 2023, at least 74 people criminal cases were initiated against Russians detained at anti‑war rallies and protests against mobilization.

Having worked with the issue of restriction of freedom of assembly in Russia for many years, we are convinced that improvements are impossible without corresponding changes in many other areas, such as improving the overall quality of regulatory regulation, guarantees of independent and fair trial, accountability and transparency of government actions, and the responsibility of officials for decisions taken. But no less important is the task of articulating specific solutions. For example, the practice of arbitrarily outlawing public events or an imbalance of responsibility that leads to the suppression of people’s desire to exercise the right to freedom of assembly is a composit of many phenomena.

In the process of reforming the situation with freedom of assembly, the following five key issues will need to be resolved:

1. The ban on spontaneous gatherings and the problem of coordination

Russian legislation does not provide for the legal possibility of holding a spontaneous gathering. Any public event must be coordinated with the authorities in advance. The deadlines for submitting a notification are strictly regulated by law, and the broad powers of the authorities to control the location and timing of actions in practice lead to their ability to prevent any undesirable events from taking place. The «uncoordinated» status of the meeting leads to a number of negative consequences — from the forceful dispersion of the event and the persecution of its participants and alleged organizers, to a ban on the dissemination of information about such actions. The steps necessary to reform the coordination system are discussed in detail in the report of the Memorial Human Rights Center and OVD‑Info in the context of the execution of the ECHR ruling in the case «Lashmankin and Others v. Russia». The main points are:

2. Restrictions during meetings

Police officers and representatives of other law enforcement agencies restrict the rights of participants in protest actions at both uncoordinated and coordinated events. Uncoordinated actions often record mass detentions, unjustified use of force against protesters and passers‑by, as well as police blocking streets, disabling or restricting mobile Internet traffic at the meeting place.

To minimize these problems, the following measures should be taken:

2. Restrictions during meetings

Police officers and representatives of other law enforcement agencies restrict the rights of participants in protest actions at both uncoordinated and coordinated events. Uncoordinated actions often record mass detentions, unjustified use of force against protesters and passers‑by, as well as police blocking streets, disabling or restricting mobile Internet traffic at the meeting place.

To minimize these problems, the following measures should be taken:

3. Collection of personal data and their use against protesters

In the context of rapid digitalization, the problem of unrestriucted government collection and storage of data on protest participants is becoming more acute, and harassment based on this information is becoming more widespread. To resolve the problem, we offer the following recommendations:

3. Collection of personal data and their use against protesters